Army Capt. Charles L. “Larry” Deibert’s hardest day in Vietnam ended when he chucked a rat out of his cockpit window. After landing at the Dong Ha base in northern South Vietnam to drop off his back-seater, Marine 1st Lt. John Haaland, Deibert nursed his bullet-riddled O-1 Bird Dog home to Phu Bai Airfield, about 60 miles down the coast, in the early hours of Sept. 11, 1967. The plane’s battle damage had accrued through several hours of intense combat over a beleaguered outpost near the Demilitarized Zone, and now, staring at the lit instruments in front of him over blacked-out South Vietnam, Deibert felt fatigue setting in.

His eyelids grew heavy, and he fought to keep his head from nodding down to rest on the two steel rods connecting the wings above him to the top of the instrument panel. As he blinked, the rat appeared, perched on one of the rods and staring at him. In a flash Deibert grabbed the intruder and flung it outside. His heart racing as he guided the plane to land, the pilot wondered if that rodent—which must have been scrambling around inside the plane through a night of jinking, shuddering and combat noise—was a “friendly” or a North Vietnamese Army rat.

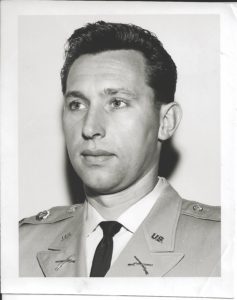

Deibert had begun his yearlong tour on Jan. 15, 1967. He had served two years in the Marine Corps (1956-58), then several years in the National Guard and went to flight school before joining the active-duty Army in January 1966. He came to Vietnam an old man—at age 31. Other pilots called him “pops” or “Captain Hair” for the thick dark shock atop his head.

Deibert helped lead the 220th Reconnaissance Airplane Company, a group of Army pilots and Marine aerial observers who directed close-air and artillery support for the Marines in I Corps, the military designation for South Vietnam’s northernmost provinces. He was known by the call sign Catkiller 4-6. The numerals indicated that he was 4th Platoon’s commander. “Cat” was shorthand for tiger and slang for the NVA.

The Catkillers had more in common with World War I biplane pilots than with those flying the “fast-mover” jets they directed toward ground targets. Their prop-driven Cessna O-1 Bird Dogs cruised at about 100 mph, often only a few hundred feet over the heads of NVA anti-aircraft gunners. Bird Dog pilots constantly changed direction and altitude, flying with crossed controls—rudder pedals pushed one way and the aileron stick held the opposite way—to keep the noses of their aircraft aimed a few degrees to the right or left of their actual heading, making it harder for NVA gunners to predict where the planes would be moments after they pulled the trigger.

Pilots like Deibert, called forward air controllers, were crucial links between ground troops and other aircraft that supported them. They flew above thick jungles and mountain highlands, watching enemy movements, establishing radio contact with ground units and circling overhead while directing artillery shelling, airstrikes by jets and medevac operations. Bird Dog crews knew the needs and capabilities of the grunts who called on them at all hours and in all types of weather, including monsoon rains, high winds and pitch-black nights. They typically logged more flight time in three months than fighter pilots did in a whole one-year tour.

The Bird Dog’s main weapons were four wing-mounted 2.75-inch-diameter rockets that shot out a bright white phosphorous smoke cloud to clearly mark enemy targets for bomb-laden jets arriving on scene. The rockets had explosive power similar to a 105 mm howitzer shell, and the phosphorus would stick to whatever it contacted, including bodies, which could be severely burned.

Deibert and his back-seater usually augmented their meager defenses with 5.56 mm CAR-15 assault rifles (an AR-15 with a collapsible stock), .45-caliber M1911A1 pistols, World War II-vintage M3 “grease gun” submachine guns and hand grenades. They used those weapons against North Vietnamese ground troops while turning the plane in a tight bank. When shooting their rifles, they held them outside the cockpit to keep the hot brass casings from falling inside the plane and potentially jamming the controls.

The O-1 Bird Dog (also known as the L-19) was designed for maneuverability and combat-zone reliability. In 1947, soon after the Pentagon reassigned most of the Army’s planes to the newly created U.S. Air Force, the Army asked aircraft manufacturers to compete for a contract to build a two-seat, all-metal plane for artillery spotting and observation.

Cessna used its reliable 170 model as a starting point, changing the pilot and co-pilot configuration from side-by-side seating to an arrangement that put the pilot in the front seat and co-pilot in the back. The company beefed up the engine but otherwise stuck with the 170’s simple design, including the fixed landing gear. Cessna tested the first military variant, called the 305, in December 1949 and won the contract, with rollout set for late 1950. A naming contest within the company was won by industrial photographer Jack A. Swayze, who suggested “Bird Dog,” a nod to the plane’s anticipated role in spotting the hunters’ quarry and then calling in overwhelming firepower. The O-1 first saw combat in the Korean War, and 3,431 were produced between 1950 and 1959.

The Army, Air Force and Marine Corps used Bird Dogs in Vietnam early in the war. But by mid-1967, the Air Force’s Cessna O-2A Skymaster—a “push-puller” with propellers in the front and back—began replacing the O-1. The last Bird Dog was retired from military service in 1974, although several are still flying in civilian hands today.

Lightweight and able to turn on a dime, the Bird Dog proved ideal for front-line service. Pilots joked about wearing it on their backs instead of controlling it. The high wing allowed for maximum ground visibility, and the plane’s superior lift made short field takeoffs and landings a breeze. With extra windows around the cockpit and a reconfigured aft superstructure, crews could see virtually all the way around the aircraft.

The Bird Dog also proved to be exceptionally rugged in combat. Pilots could keep it airborne with multiple bullet holes in the wings, Deibert recalled. “The skin is thin,” he said. “A round will go through it and just leave two little holes. You can look like a piece of Swiss cheese, and it’s no big deal unless a bullet hits the pilot or a gas line. It was just an awesome, awesome little airplane.”

In mid-1967, after an overwhelming enemy artillery and rocket attack damaged several parked aircraft at Dong Ha, the 220th Reconnaissance company’s headquarters moved south to Phu Bai. Bird Dog crews still flew up north, however, with an average of three O-1s operating out of Dong Ha during the day and one overnight. If a Marine unit was hit at night or enemy artillery fired on Dong Ha itself, the on-duty Catkillers would scramble into the air, sometimes without time to call for proper clearance from air traffic control, and look for muzzle flashes.

If the enemy was spotted, the Bird Dog crew would radio for payback in whatever form was available—Army or Marine Corps artillery, rockets from Navy barges just offshore or even shells from the battleship USS New Jersey in the South China Sea. Roughly three-quarters of the time, however, the punishment came from airstrikes by carrier-based Navy and Marine F-4 Phantoms, A-4 Skyhawks and A-1 Skyraiders. Air Force jets based in Thailand also made occasional strikes.

On missions over North Vietnam to hunt for artillery or search for downed aircrews, the Catkillers flew in pairs. One Bird Dog would stay low, sometimes just 300 feet above the jungle treetops. The other would fly at an altitude of 2,000 to 5,000 feet and keep the lower plane in sight in case it went down. Deibert flew 73 such missions, code-named “Banjo,” but most of his 570 sorties took place just south of the DMZ, where Marines were always in trouble.

Con Thien: The “Hill of Angels”

What Deibert calls “that terrible day” took place at Con Thien, a Marine outpost on a barren 525-foot hill about 2 miles south of the DMZ and 8 miles west of the South Vietnamese coast. The outpost was positioned on the southern edge of an east-west barrier being constructed along the DMZ—from the South China Sea to Laos—to block the flow of NVA troops into South Vietnam. The barrier line was marked by a cleared area about 600 meters (656 yards) wide, where the Pentagon planned to lay down barbed wire, mines and electronic sensors that could detect enemy movements. Promoted by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, it was called McNamara’s Line.

The barrier was never completed, and Con Thien, which means “hill of angels,” became known as the least defensible of any American base because it was so close to North Vietnam and only large enough to house one reinforced battalion. Since the Marines had arrived there in December 1966, North Vietnamese forces had been regularly probing ground defenses and lobbing artillery at the outpost. Locating and silencing the NVA’s 130 mm guns proved tricky, even with saturation bombing by B-52s, because the weapons were operated by highly mobile units from bases safely situated across the northern border in caves and tunnels. As 1967 wore on, Marines came to hate the hill, which was soon stripped of all vegetation by constant artillery attacks that forced them into mud-filled trenches and bunkers. They tried their best, with patrols and ambushes, to keep the enemy from constructing fortified positions close by. Every 30 days, a new battalion would take its place on the hill, which earned nicknames like “the Meat Grinder” and “Our Turn in the Barrel.”

When North Vietnamese commanders looked at Con Thien, they saw shades of Dien Bien Phu, where a seven-week siege in 1954 resulted in a decisive defeat of French forces in a similar situation. The stage was set for a massive test of wills. Capturing Con Thien would open a new supply route to the south, provide a staging ground for an attack on the major American installation at Dong Ha and—in the worried opinions of American military officials—produce a major propaganda victory. Gen. William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, declared that Con Thien was less a military engagement than a political one. “Their target is American public opinion,” he told reporters in September 1967.

At that time, elements of the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment, were patrolling near the Con Thien outpost, and that September would be the deadliest in the unit’s history.

At about 5 p.m. on Sept. 10, 1967, Deibert and Haaland took off from Dong Ha for a mission that was immediately scrapped. Landshark Bravo, the air traffic controller responsible for the I Corps area, ordered their Bird Dog to Con Thien as fast as possible. Flying at 2,000 feet, they raced straight toward an unfolding crisis. An estimated 1,400 North Vietnamese troops, advancing behind a screen of smoke and tear gas, surged across the DMZ in a coordinated attempt to take Con Thien.

Earlier that day, the NVA had struck I Company of the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, while the unit was on a reconnaissance patrol southwest of Con Thien. Outnumbered 6-1, the Marines battled North Vietnamese troops in savage close-quarters fighting but suffered heavy casualties and were driven from their position. As the situation worsened, I Company 1st Lt. R. R. Zappardino radioed his position to Deibert and Haaland, then popped smoke to mark the unit’s location and watched the tiny plane fly in. Intense enemy fire prevented helicopters from resupplying the Marines or evacuating the wounded, but Deibert wouldn’t be stopped. He flew his Bird Dog overhead to assess the situation, maneuvering in tight, unpredictable turns to avoid the NVA fire.

The plane was pelted with a “heavy volume of .30 caliber, .50 caliber and 37 mm flak aimed at his airplane,” according to Haaland’s statement after the battle. Three times Zappardino and others on the ground told Deibert to get out of the area. Deibert and Haaland refused to leave the Marines. They stayed in contact with the men below and radioed the locations of visible enemy positions.

In the meantime, Landshark Bravo ordered all aircraft bound for bombing runs on Hanoi to divert to Con Thien and support the Marines. As the first of several fighter-bombers approached the scene, Deibert scribbled all of their call signs and the altitudes of their holding patterns on his windshield in grease pencil. Near that list, dead center on the windshield, was a hand-drawn plus sign that served as an improvised gunsight. If Deibert sat square in his seat, the plus sign was right in front of his eye, and he could use it to aim his four white phosphorus smoke rockets when he fired them at ground targets.

Catkiller 4-6 hits his mark

After spying three enemy anti-aircraft gun positions close together, Deibert armed one of his rockets, aimed and dove on his target for a split second, pressed the trigger and immediately went back to evasive maneuvers. Normally, a Bird Dog pilot would fire toward his target, see where the rocket hit and then radio an aiming adjustment to the jets to guide their bomb drops (directing them, for example, to a spot 50 meters west of the smoke). But Deibert’s rocket went exactly where it was aimed, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy gun crews. The Bird Dog pilot told a pair of A-4 Skyhawks to hit his smoke, and the jets took turns finishing the job while the Bird Dog found another target.

“We had aircraft on station holding in circles every thousand feet” waiting in turn to drop ordnance and head home, recalled Deibert, who said he and Haaland were like two conductors leading a massive symphony. Haaland had “all three radios going on his frequencies,” Deibert said, “and I had all three radios going on the ones that I was using. It was so busy, and it was so loud.” Dipping and dodging at altitudes between 400 and 900 feet, Deibert was “slamming the stick, just back and forth and sideways” for seven stomach-churning hours, the pilot said. The occasional loud thud announced an enemy hit on the Bird Dog.

Whenever the plane’s nose tipped over into a dive, both men would rise into their harnesses and, for a moment, sand from the floor would float all around them. Then as Deibert pulled back on the stick, their bodies would smash back into their seats.

Eventually Deibert found a route that allowed four Marine Corps UH-34D helicopters to use the hilly terrain as a screen from enemy fire so they could land, deliver ammunition and evacuate the seriously wounded.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As several hundred NVA troops rushed toward a unit of pinned-down Marines, Deibert heard a young radio operator screaming into the mike for help. “I’m thinking, God, he’s terrified,” Deibert said. He soon realized, however, that in the deafening roar of battle the men had to scream their words. When he was on the radio talking to the Marines, Deibert could hear the “crackling of the rifles and the machine guns” and “hand grenades going off.” During the chaos, an enemy round smashed through the windshield and grazed his face.

Several of the attacking jets circling in holding patterns were running out of fuel. Landshark Bravo sent another Bird Dog to join the fight. That plane flew to an area about a mile west of Deibert. Its pilot directed jets that flew northbound on a bombing run, then made a left-hand turn away from the battle below and circled back for additional strikes, while Deibert, to the east of Con Thien, put his jets on the same northbound approach, with a turn to the right before circling back to the attack site. The jets scored direct hits on an NVA ammo dump, creating dozens of secondary explosions and a fire that burned for nine hours.

Low on fuel, Deibert and Haaland had to return to Dong Ha. During the refueling, they got out of the plane for about eight minutes to help the crew chief rearm it with four rockets. Back in the air, they remained above the besieged battalion into the early morning hours.

Around 2 a.m. on Sept. 11, Catkiller 4-6 finally left the area. Deibert landed at Dong Ha to drop off Haaland and then threw the troublesome rat out the window. Deibert and a new back-seater returned to the scene in an undamaged Bird Dog later that day but had no further contact with enemy troops. “They had all blended into the jungle, and the good guys were around picking up Americans.” Deibert said. It looked like the enemy had dragged its casualties away using meat hooks, he added.

Deibert, Haaland honored

The NVA continued to pound the hill at Con Thien for the rest of September. Toward the end of the year the fighting died down as the NVA regrouped and launched an attack in January 1968 on the Khe Sanh Marine base, which remained under siege until early April when soldiers of the 1st Cavalry Division (Air-mobile) arrived.

For his heroics over Con Thien, Deibert was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army’s second-highest combat honor. Haaland received the Silver Star, the third-highest valor medal. During the battle at Con Thien, 38 Marines were killed and 192 wounded. Approximately 150 Americans on the ground got through the battle unhurt. The NVA suffered 241 confirmed dead, with an additional 450 probable. Deibert received credit for 88 confirmed and 150 probable kills. The ground crew counted 23 bullet holes in his Bird Dog.

In many ways, directing the airborne counterattack at Con Thien was the most notable of Deibert’s Bird Dog exploits, but it was only one day in a year flying unarmored Cessnas over extremely dangerous real estate. Bullet holes were punched in other Bird Dogs he flew, although Sept. 10 made up about half of his total from groundfire in 1967. Deibert also had to make three forced landings near the DMZ that year, and he radioed a 10-minute emergency piloting lesson to a Bird Dog back-seater whose pilot was shot in the head, leading to a messy—but successful—landing.

For troops in trouble, an approaching Bird Dog was a comforting sound, a sign that close air support, resupply or evacuation would soon follow. The 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, made Deibert an honorary member of their unit after the war, hanging his DSC next to the 11 Navy Crosses and one Medal of Honor they received in-country and embracing him every year at their reunion.

Paul X. Rutz, a former Navy lieutenant, is a portrait painter and freelance writer.