During the Vietnam War, the skies were filled with fast jet fighters, huge bombers, droning transports and thudding helicopters. They were hard to miss. Other aircraft, less noticed but no less important, provided neither guns, nor bombs or transportation but something that was just as crucial to men fighting the ground war—a pair of eyes in the sky. These planes, piloted by forward air controllers, flew above the battlefield looking for enemy forces and then directed bombers or fighters to strike them.

The Vietnam War’s FACs were the legacy of a concept that originated during the Civil War. In 1862, the Union Army used hydrogen-filled balloons to scout and report the positions of Confederate troops and artillery on the York-James Peninsula in Virginia. Aerial observers were also in the open cockpits of wood-and-fabric biplanes over the Western Front during World War I, taking note of enemy troop movements, artillery emplacements and other useful details.

Since then aerial observers have had a nearly unbroken history in warfare stretching through World War II, Korea and Vietnam—on into the 21st century. Tiny, slow and fragile airplanes carrying a single aviator who could assess an evolving ground battle and decide what air action to take became essential elements in modern warfare, even in the age of the jet.

Hundreds of FACs in the Air Force, Navy, Army and Marines provided vital assistance in Vietnam. They were the link between friendly ground units and the “fast movers,” the tactical air fighters. If a Marine, Special Forces or other Army unit needed help from the skies, the FAC climbed into his little Cessna O-2A Skymaster observation plane and flew into so-called “Indian Country.” As he drew closer, the pilot established radio communication with the ground unit to learn where the enemy was and more important, where the friendlies were.

The FAC, on call at any time and place, had no real weapons, other than his sidearm. His most important tools were three radios and a load of 10 white phosphorus rockets used to mark enemy targets for American planes coming in with bombs. The radios—set to communicate with the air base, ground forces and strike aircraft— could only be used one at a time. Fast reactions were required to flip from one radio to another while calling in airstrikes and keeping both the air base and ground units informed. An FAC had authority to request airstrikes on the enemy. If ground units were in danger of being overrun, he could even divert aircraft involved in other operations.

Keen eyes, a steady hand on the controls and a quick mind were essential to assessing an evolving situation. Those were the qualities that earned Air Force Capt. John P. Calamos a reputation as one of the top forward air controllers of the war. Serving with the 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron at Da Nang Air Base, he flew some 400 flights as an FAC and logged more than 1,000 hours in the air. One harrowing night over Thuong Duc Special Forces base in September 1968 assured his place in the history of the Vietnam War.

Calamos, the son of Greek immigrants, was born in Chicago and had “only flown once or twice” growing up, he said. “The idea of someday flying jets in formation seemed like a pretty good accomplishment.”

He enrolled in the Air Force ROTC at the Illinois Institute of Technology and earned his commission in 1963. Calamos went on active duty in 1965 and got his pilot training at Webb Air Force Base in Texas. “I had aimed to be a fighter pilot, but was assigned to fly B-52s,” he said. His wing was stationed at Beale Air Force Base in California.

Calamos did not get to spend much time in the big B-52 Stratofortress. “I was ordered to go to Vietnam as a forward air controller,” he said. After going through FAC training in Florida, he arrived at South Vietnam’s Da Nang Air Base in May 1968. “It was quite a shock to go from the biggest bomber in the Air Force to the little Cessna 0-2A,” Calamos said.

The Air Force set up operations at Da Nang Air Base in 1962 to support U.S. military forces and South Vietnam’s army. Originally used for troop transport aircraft, the Da Nang facility had expanded by 1965 into one of the largest combined air bases in the Far East. Dozens of Air Force, Army and Marine transport, tactical bomber, reconnaissance, attack and tactical fighter units were stationed there.

On May 8, 1965, Da Nang became home to a new unit, the 20th Tactical Air Support Squadron. Originally slated to receive 30 aircraft, the 20th TAAS spent most of the summer of 1965 with fewer than 20 Cessna O-1 “Bird Dog” observation planes because of slow aircraft deliveries by the Army.

After the pilots assigned to the squadron completed a series of familiarization flights, they were given various duties in the region.

One of the assignments was to fly interdiction missions to spot enemy troop movements, call in airstrikes and support air rescue operations over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, an operation designated Tiger Hound. At least three forward operations bases—Khe Sanh, Kham Duc and Kontum—were established to support the FAC mission.

In July 1966 the 20th TASS was assigned to what were called Tally Ho interdiction missions in the Operation Steel Tiger area of Laos, extending 30 miles north of the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam.

By the time Calamos arrived at Da Nang in May 1968, the 20th TASS had abandoned the O-1 Bird Dog, whose origins went back to 1947, and was flying the more capable Cessna 0-2A, a military variant of the civilian Model 337 Skymaster. In late 1966, the 20th TASS was the first squadron to receive these planes. The Air Force contracted for 350 0-2A Skymasters in all.

Nicknamed the “Oscar Deuce,” the O-2A had twin engines with a propeller on the nose and one at the rear, known as a tractor-pusher configuration, under a high wing between twin tail booms. With large, slanted windows providing excellent visibility, the 0-2A was perfect for the FAC role, yet provided nothing in the way of pilot protection.

The O-2A’s most valuable asset was its excellent range. At a cruising speed of about 140 to 160 mph, the Cessna could fly more than a thousand miles. It was retired when the more advanced North American-Rockwell OV-10 Bronco light attack and observation plane entered service in 1969.

The O-2A, with its low cruising speed, could “loiter” over and around a relatively small battle area, which helped the pilot stay abreast of the situation on the ground. McDonnell F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers and North American F-100 Super Sabre fighters moved far too fast for accurate bombing when there was less than a few hundred yards between enemy and friendly forces. Pinpoint precision was paramount in airstrikes when American and allied forces were close by.

“The FACs orbited the area, controlling the airstrikes by firing white phosphorus rockets to mark the target,” Calamos said. “We knew where the friendly and enemy ground units were. That’s what the rockets were for. The jet fighters could not drop unless we told them that they were ‘cleared in hot,’” meaning the target was clear of friendlies and could be hit. The FACs told the attack aircraft what the target was and which direction to approach from.

Downed airmen and friendly infantry carried various colors of smoke flares that enabled the FACs to locate them under dense forest canopy. However, the North Vietnamese Army used flares too, in an effort to confuse the American forces.

Calamos had once received a call from an infantry unit that was under attack by NVA troops deep within a forest. “I was on the radio with the jets and the guys on the ground,” he recalled. “I needed to pinpoint where they were, and the guy says, ‘I’ll send up some red smoke.’ Suddenly there were two red smokes coming up from the woods. That meant the enemy was listening in and using [red] flares to make it hard for any rescue attempt. So then the guy says, ‘I’ll send up green smoke!’ Then I saw two separate green smokes.”

Calamos knew the North Vietnamese soldiers were copying the flare color. On the ground, the American infantry figured that out too and tried something else. “While this was happening the jets orbited nearby, waiting for their cue,” Calamos continued. “Then the guy radios, ‘Sending up yellow smoke!’ And only one yellow smoke comes up. At that point the infantry guy said: ‘I don’t have yellow smoke! Get them!’ Then I radio ‘Cleared in hot! Target is the yellow smoke!’”

FACs orbited within sight of the target while the jets moved in and dropped their ordnance. One at a time the bombs went off, obliterating the FAC’s view of the impact zone, but when the smoke cleared, he had to decide whether to call in another bomb run. Often many bomb runs were required to finish the job against tenacious North Vietnamese troops.

The low altitudes and loitering that were necessary in their work put the FACs in almost constant danger of being shot down and captured. “We tried to stay clear of groundfire,” Calamos said, “remaining above fifteen hundred feet and not flying straight and level for too long. There was often a lot of groundfire, even small arms stuff. When we fired the rockets we had to descend to make sure we hit our target, but right after that it was back to fifteen hundred feet again.”

By 1968 the FACs were performing a variety of vital air support roles, almost always alone. They collected intelligence on NVA movements, weapons and strength, and acted as communications links between ground and air units.

When Calamos was flying FAC missions in the fall of 1968, the Special Forces camp at Thuong Duc, established in late 1965, was one of the many Green Beret fortifications the U.S. military had constructed in South Vietnam near the Laotian border to monitor NVA activity in the region. They were manned by A-Teams of the 5th Special Forces Group and paramilitary units from the region’s Montagnard tribes, one of South Vietnam’s ethnic minorities.

Camp A-109 at Thuong Duc was in a river valley about 25 miles southwest of Da Nang. The Special Forces team occupied the camp’s center compound, connected by a complex network of communications and land routes to an outer ring of Montagnard camps and outposts. The camp was well-positioned along two ridges with a commanding view of the river valley below. The nearby Da Nang Air Base added to its tactical importance. The camp also was on one of the major routes used by the NVA for attacks on U.S. installations in the region. The North Vietnamese were determined to eliminate it at any cost.

Even though Special Forces camps had mortar and artillery crews, they relied heavily on what is now called “close air support” and during the war was dubbed “calling in the whole world.” The FAC’s job was to identify the enemy and bring whatever aircraft were needed to counter the threat. “There were about six of us at Da Nang,” Calamos said. “We were assigned sectors around Quang Nam [province], which included the Thuong Duc camp.”

In September 1968, NVA forces began preparing a major assault on Da Nang—and the first place on their hit list was the Thuong Duc camp. Two regiments of NVA infantry, about 3,000 troops in all, stealthily moved mortars and artillery to surround the camp and its outposts on three sides. The assault began 2 a.m. on Sept. 28 when elements of the NVA 21st and 141st regiments attacked and overran outposts Alpha and Bravo, around 600 yards from the camp perimeter. The Special Forces troops and Montagnards led successful but bloody counterattacks to retake vital outposts.

The NVA increased the pressure throughout the day with mortar and artillery attacks on local villages to establish more concentrated fire on the camp. This vicious tactic cleared an area so NVA could move its short-range mortars closer to the camp. The Special Forces and Montagnards continued to repel the attacks as night fell.

That was when Calamos, call sign “Lopez 58,” was sent to relieve the FAC who had directed airstrikes during the day. By this time the enemy had lost the initiative but still pushed hard to break through the American perimeter.

In the darkness of night, Calamos, in his little “Oscar Deuce,” watched the ground for flashes of gunfire, tracers and explosions. “I had tracers coming up at me,” he said. “I could not see the enemy troops, but I knew where they were from the groundfire.”

The opposing forces were just 200 feet apart, according to Calamos, who was getting his information from the Green Berets. “The bad guys were too close for the jets to hit with any precision,” he said. “The night made it even more risky.” More light was needed. He called in flare planes, which dropped a steady stream of parachute flares to illuminate the battlefield in an eerie stark white light.

Calamos asked the base at Da Nang, which had been launching airstrikes during the day, to send in more jets loaded with ordnance. Phantoms and Super Sabres streaked in low and disgorged cluster munitions and general-purpose bombs. Calamos assessed the damage and effectiveness of each strike. The bombs detonated in bright yellow and white flashes that left spots in his eyes.

Small fires flared, adding to the macabre night landscape and revealing an inferno of bodies and weapons. Yet the remnants of the two NVA regiments refused to give up. They continually probed to find a weak spot in the American and Montagnard perimeter.

Calamos spotted those attacks. More white rockets streaked down as his call of, “Cleared in hot!” came over radio frequencies. The FAC called for a second full strike on the determined enemy.

“The weather was poor, and it sometimes interfered with my being able to see what was happening,” he said. “The second strike came in and hit right where I had put my rockets.”

Calamos’ call brought in one of the truly remarkable aircraft of the Vietnam War.

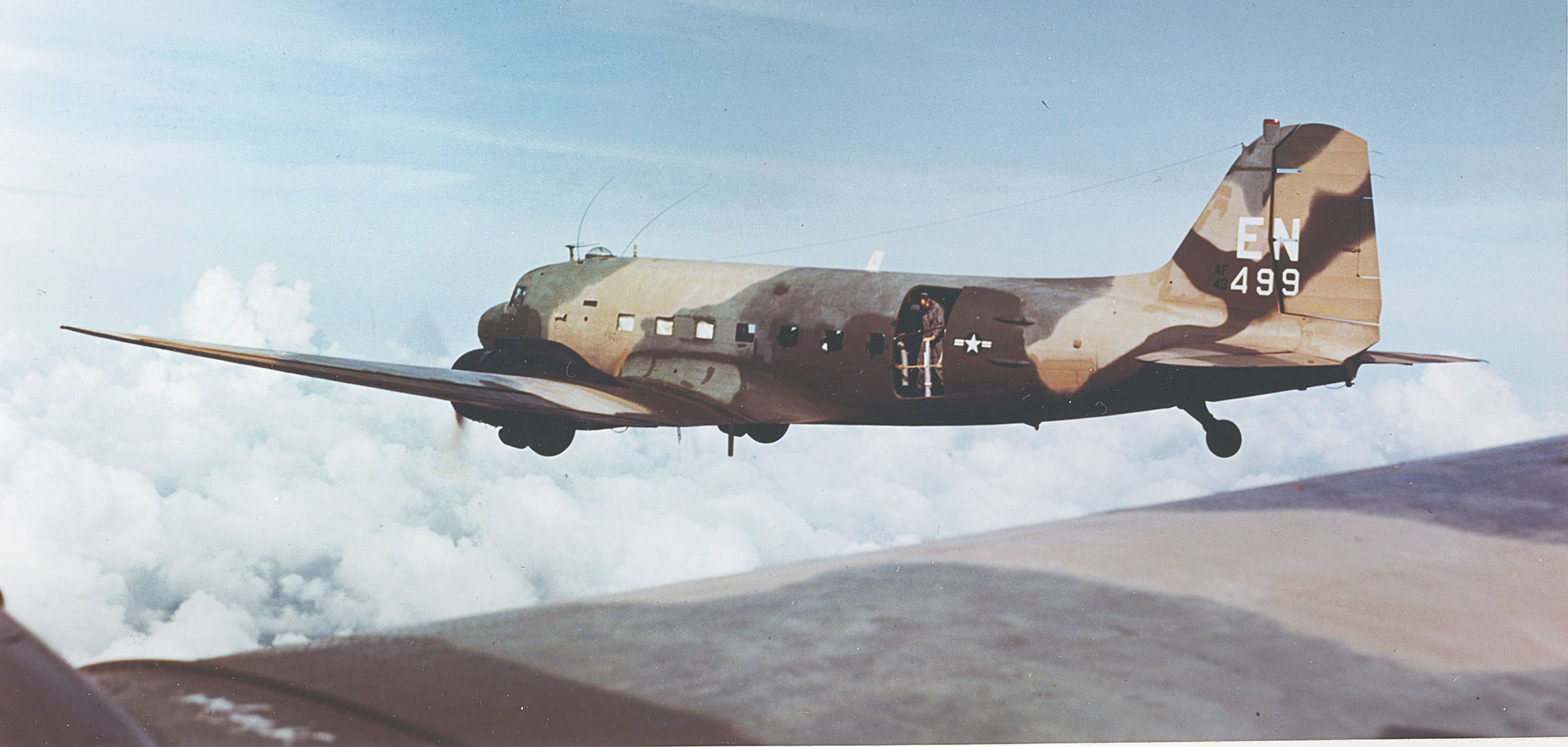

Nicknamed with typical American humor as “Spooky” and “Puff the Magic Dragon,” the Douglas AC-47 was the ultimate gunship at that time. This converted C-47 transport plane carried three 7.62 mm General Electric rotary miniguns mounted in the left side cargo door and two windows. Each gun had six rotating barrels, like a Gatling gun, and fired 2,000 to 6,000 rounds per minute from a 5,000-round belt. The AC-47 often hauled a combat load of 24,000 rounds.

Spooky’s pilot controlled the guns as he peered through crosshairs on his left-side window. The plane circled in what is known as a counterclockwise “pylon turn,” in which the pilot was able to keep the stream of hot lead aimed in a cone of fire at an area about the size of a football field. Groundfire and mortar explosions gave the pilot a clear aiming point. At night the tracers looked like orange laser beams, making aim easier. The steady stream of bullets literally tore through the foliage, leaving death and carnage wherever it touched. That concentrated firepower inflicted heavy casualties on the NVA troops the night of Sept. 28.

After four solid hours of orbiting over the battle at Thuong Duc and calling in every aircraft that could be of help, Calamos was relieved at 2 a.m. on Sept. 29 and flew back to Da Nang. The Special Forces camp was later secured and the NVA driven away. It had been a long and bloody fight. At least 68 NVA were killed in direct assaults on the camp, while hundreds more were killed in the airstrikes. U.S. and friendly casualties were light, although exact figures are unavailable.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The FACs working with Air Force and Marine aircraft played a major role in protecting the Thuong Duc camp and surrounding area from an NVA assault that threatened to overrun the American and Montagnard forces.

Calamos’ outstanding work over the battlefield earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded to personnel in all branches of the armed forces who display “heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.”

“I flew over 1,000 hours during my tour in Vietnam,” Calamos said, and “833 of those hours were in combat.”

After rotating back to the States in May 1969, Calamos returned to B-52 bombers, based at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota. He spent five years on active duty and 12 more in the Reserves flying Cessna A-37 attack planes. One can’t help but wonder what the Air Force had in mind when it took Calamos from B-52s and made him an FAC in the O-2A Cessna, then put him back in the Stratofortress. Regardless, the Special Forces soldiers who served at the Thuong Duc camp are very glad the Air Force did that. V

Mark Carlson is a regular contributor to over a dozen military history magazines and the author of The Marines’ Lost Squadron—the Odyssey of VMF-422 and Flying on Film—A Century of Aviation in the Movies 1912-2012. He lives in San Diego.

This article appeared in the June 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine.