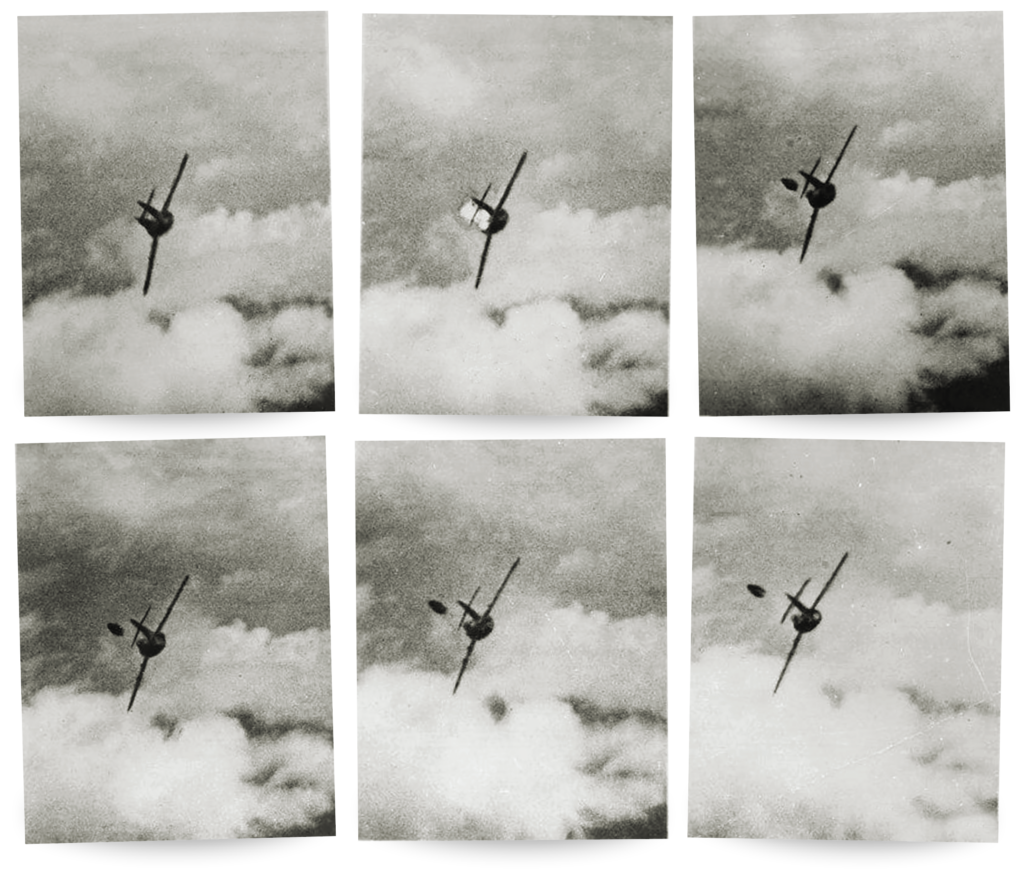

In its June 8, 1953, issue, Life magazine included a full-page spread with four blurry images of a North Korean Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 getting shot down over Korea. They were taken by the wing-mounted movie camera of a U.S. Air Force F-86E Sabre as it engaged the enemy jet near the Yalu River on May 14. The grainy black-and-white photos depict the crippled MiG after it was hit by a burst from the Sabre’s six .50-caliber machine guns. They show the jet in flight, followed by a bright flash as an explosive charge propels the pilot and his ejection seat away from the doomed aircraft.

The 23-year-old American aviator who scored the victory and took the images was a recent West Point graduate who had arrived in Korea just six months earlier. It was his first victory as a combat pilot and the photospread in Life gave him his first moment in the spotlight. It was not his last.

The pilot was Lieutenant Edwin E. Aldrin—better known to the world today as Buzz. He would rocket to fame more than a decade later as a space-walking astronaut with Gemini 12 and then again a few years later as the second man to walk on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission.

However, in 1953, Aldrin was relishing his first air-to-air victory—even if it was lacking in thrills. His quarry hadn’t realized there was an American in the sky, never mind on his tail.

“It was a singularly undramatic experience: no dogfight, no maneuvers, no excitement. I simply flew up behind the enemy and shot him down,” Aldrin wrote in his 1973 autobiography Return to Earth.

The real excitement came a few weeks later when the photos appeared in Life. Aldrin flew with the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing, which was in constant competition with its rival 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing. “That was a real coup over those glory boys of the 4th,” he said in his 1989 book, Men from Earth. Aldrin also earned a Distinguished Flying Cross for the kill.

At the time, Aldrin was just coming into his own as a fighter pilot, using skills that appear to have been something of a family tradition. He had been born in New Jersey on January 20, 1930. His father, Edwin Eugene “Gene” Aldrin Sr., became a U.S. Army aviator after World War I and was an officer in the Army Air Forces during World War II. Between the wars Aldrin Sr. had once served under air power pioneer William “Billy” Mitchell. He retired as a colonel from the Air Force Reserve in 1956.

Aldrin Sr. also had an interest in space and in 1915 he had studied rocketry at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, under the guidance of Robert H. Goddard, inventor of the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket. He later served as consultant to the manned space flight safety director of NASA, where he would cross paths with his son. He died in 1974.

Aldrin Jr. pursued his own dream of flying by graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1951 (the U.S. Air Force Academy was not established until 1954). He later earned a doctorate in astronautics from MIT, where his father had received a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering in 1918.

Fresh out of West Point, young “Buzz” (the nickname came from the way a sister mispronounced the word “brother”; Aldrin made it his legal name in 1988) found himself on the way to Korea. The “police action” there had United Nations forces, including the United States, defending South Korea after the communist North (backed by China and the Soviet Union) invaded on June 25, 1950. In Korea, Aldrin demonstrated a proficiency as a jet pilot that helped him become mission leader in just a few months. “You always started as a wingman to get experience and see how things work,” says Michael Napier, an RAF fighter pilot in the Gulf War and author of Korean Air War: Sabres, MiGs and Meteors, 1950–53. “Aldrin was a very impressive pilot and always looking for opportunities. From what little I know about his character, he was feisty, too. That’s certainly an advantage in those situations.” Aldrin had one kill under his belt. His second victory would prove to be far more difficult than his first.

The epic duels between F-86s and MiG-15s locked in soaring, spiraling dogfights have become emblematic of the Korean War. The jets often clashed in large numbers over MiG Alley, the name given by United Nations pilots to the area near the Yalu River, which marks the border between North Korea and China. The two airplanes were similar in appearance, with swept-wing designs and open-nose intakes to provide the air flow necessary for high speeds and high-G maneuvers.

“Both were top-of-the-line fighters,” says Dr. Michael Hankins, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “There are little differences here and there in terms of slats and hydraulic controls, but they are pretty evenly matched in a one-on-one dogfight. Overall, the Sabre is a more effective airplane.”

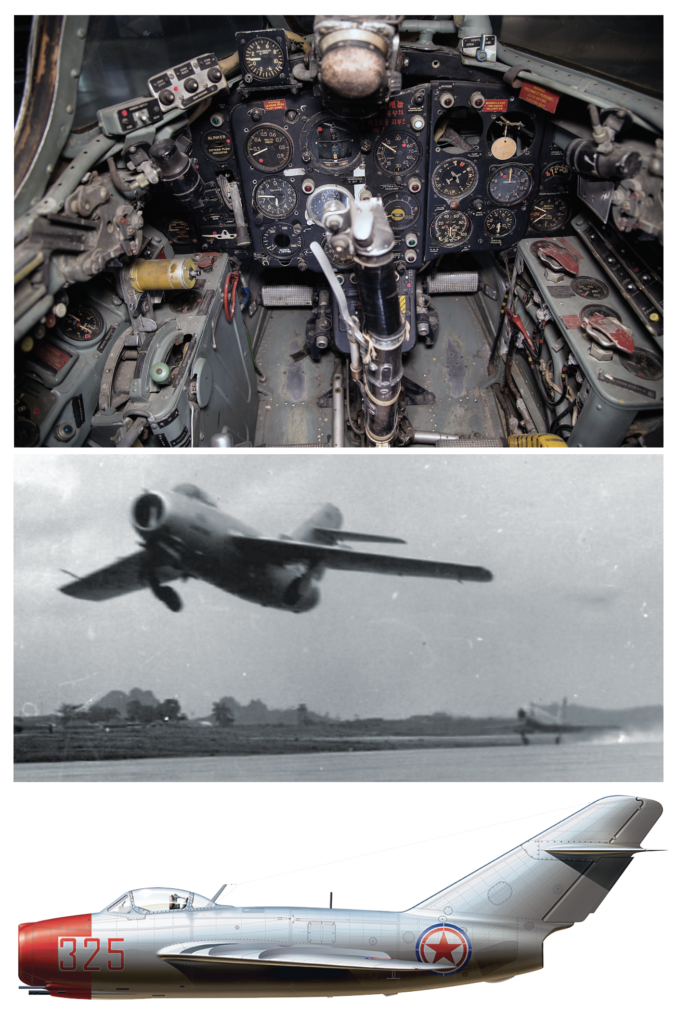

In its day, the MiG-15 was a formidable fighter itself. It reached Korea in November 1950, when the Soviet Union deployed two regiments of the 324th Fighter Aviation Division to aid the overmatched North Korean air force. Featuring the Klimov VK-1 engine, the jet could reach speeds of nearly 700 miles per hour—up to 100 mph faster than American jet fighters like the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star, Republic F-84 Thunderjet and Grumman F9F Panther. In Korea, the Soviet swept-wing turbojet aircraft overwhelmed the straight-wing first-generation jets flown by the United States and its United Nations allies—literally flying circles around the now-obsolete airplanes.

In addition, the Soviet jet was heavily armed, with three autocannons: two 23mm NR-23s and a single 37mm N-37. Intended as a means to destroy the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, the MiG-15’s weapons could be equally devastating—if not more so—on fighter aircraft. The explosive rounds packed a wallop but at the expense of a slower fire rate and limited ammunition reserves on the plane. The two firing systems offered another disadvantage, too. The two smaller-bore cannons were on the left side of the fuselage while the big gun was on the right, meaning a pilot had to be aware of what gun he was using to aim correctly.

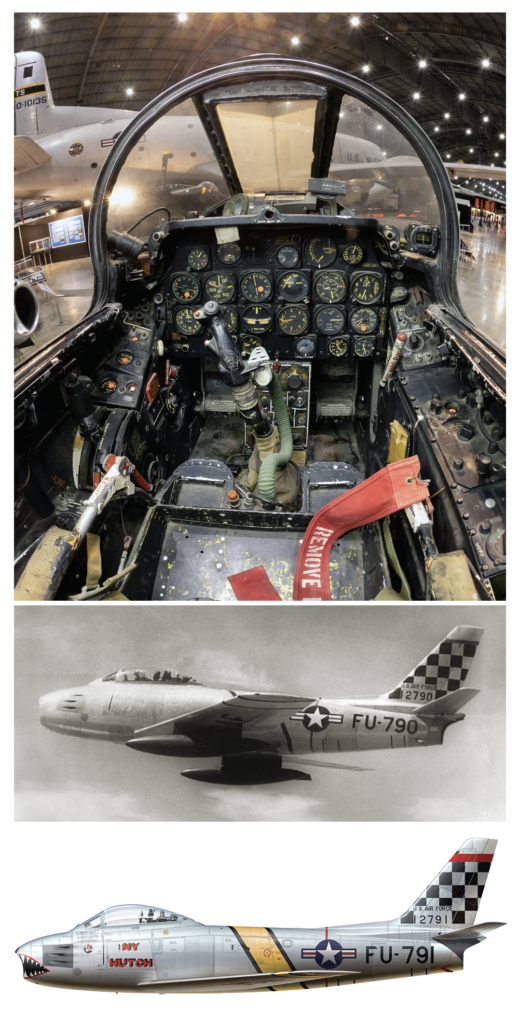

The jet’s superiority was quickly challenged in December 1950 when the United States rushed three F-86 squadrons to counter the MiG-15 threat. Built by North American, the Sabre featured the General Electric J47-GE-7 jet engine through late 1953. That engine produced 5,200 pounds of thrust with a top speed of 687 mph—a close match with the MiG-15. However, the F-86 could reach only 45,000 feet, about 5,000 feet below the Soviet-built jet’s ceiling. This gave enemy pilots momentum during an attack, as well as the element of surprise when they dove on American aircraft. The MiG-15 could make tighter turns, but the F-86 could descend faster, an advantage in a downward spiraling dogfight.

The Sabre’s six Browning .50-caliber machine guns featured a fast rate of fire—about 1,500 rounds per minute, which was more than adequate to inflict serious damage on an enemy plane. Though not as powerful as cannons, the F-86’s weapons were aided by a computerized aiming system that automatically determined the target’s range. Guided by radar, the A-1CM gunsight proved a game changer by providing highly accurate firing and impressive kill statistics. By the end of the war, the U.S. scrapped the machine guns and added four 20mm cannons to the F-86H. The future of American fighter aviation would be based on variants of this weapon as faster and more technologically advanced jets were introduced over the years.

The Sabre and Mig-15 clashed for the first time over Korea on December 17, 1950. Flying an F-86A, Lt. Col. Bruce H. Hinton of the Air Force shot down a MiG-15 in that showdown. By war’s end, Sabres scored 757 victories in head-to-head matchups against the enemy aircraft while losing only 103 encounters.

While Aldrin was pleased to get his first victory, the celebration was decidedly low-key. “There were no celebrations awaiting me as there would have been in all previous wars,” Aldrin recalled. “I didn’t even get to paint a MiG on the nose of my aircraft—I had no aircraft of my own; I flew whatever was available. That night I bought drinks for several of my friends and that was that.” The return to war so soon after World War II likely dampened celebratory spirits, as did the threat of annihilation by two nervous superpowers equipped with nuclear weapons facing each other through their proxies in Korea.

The dawn of “push-button” warfare may have also had an impact on how pilots viewed success in combat. Advancing technology altered the scope of combat to the point where long-distance attacks with missiles were possible against an enemy that wasn’t even visible. “The Korean War was the first of what historians called the impersonal conflicts,” Aldrin wrote.

Impersonal or not, Aldrin continued to take to the skies over Korea. On June 7, 1953, he scored his second kill. “If the first MiG was a piece of cake, the second was the hairiest experience I’ve had flying machines in this planet’s atmosphere,” he said.

On that day, Aldrin’s wingman had to abort due to engine problems shortly after takeoff. The young lieutenant continued on alone, trying to catch up with three other Sabres over MiG Alley. Called Tiger Flight, this unit of the 39th Fighter Interceptor Squadron flew the more advanced and faster F-86Fs. Aldrin was piloting a slower F-86E and had a hard time keeping up with the American jets.

The leader of Tiger Flight spotted a MiG airfield and descended to attack. Aldrin jettisoned his spare tanks and followed. He knew he couldn’t catch the other Sabres but didn’t want to be left behind. As he descended, his jet began to shake and roll as he approached Mach 1—“a forbidden speed for the Sabre,” he recalled. Just as the other pilots leveled off at 5,000 feet, Aldrin was surprised to see another aircraft suddenly banking off his right wing. He caught sight of the plane’s tail and recognized it as a MiG-15. Aldrin throttled back and activated his speed brakes so he could get behind the enemy jet.

The enemy pilot had spotted Aldrin’s aircraft at the same time. He turned into the American, who then realized he was going to overshoot the MiG and wind up with the enemy on his tail. Aldrin made a hard right turn to get on the bogie’s left side. The pair of combatants repeated the maneuver several times as they hurtled toward the earth. “Fighter pilots call this a scissors, the two opposing aircraft crossing like blades of a broken scissors,” Aldrin said. “Cross and cross again, with each pilot trying to slice the sky more sharply than his enemy.”

Aldrin saw the ground rushing up at him as the two airplanes continued to cross paths during their descent. The contest became a game of chicken as each pilot waited for the other to pull out of the dive. The enemy pilot broke first. Aldrin quickly jumped behind him and tried to line up the MiG in his gunsight, only to discover that the high-G turns had jammed the aiming device. If he was going to score this victory, Aldrin would have to do it on his own. Using the nose of his Sabre as a gunsight, the young lieutenant fired a quick burst and saw the spark of a tracer striking the wing of the enemy jet. Aldrin then throttled up and chased the MiG into a steep right turn, where he had a clear shot. “I fired and the bright tracers jumped along his wing from the root to the tip,” he recalled. “Smoke shredded back toward me. He rolled out of the turn and pitched over in a shallow dive. I gave him two more bursts. His nose came up and he started to stall out.” Aldrin saw the MiG’s canopy pop off and then a bright flash from the ejection charge. Still in his seat, the pilot blasted away from his stricken jet with an “implausible” red scarf trailing behind him. As Aldrin soared past, he couldn’t see if the parachute deployed or not.

As thrilled as he was with the kill, Aldrin knew he had to be careful about what he said when he got back to base. He had been flying north of the Yalu River and over China at the time—an area where U.N. pilots were technically forbidden to venture. “The reason for the rule was pretty clear,” the Smithsonian’s Michael Hankins says. “Everybody was worried about starting World War III, especially with nuclear weapons in play. We didn’t want to see any more involvement by the Chinese—or even the Russians for that matter.”

Still, U.N. pilots often ignored the directive. “It seems that crossing the Yalu and pursuing MiGs into a technically forbidden area was not uncommon,” Hankins says. “A lot of pilots were doing that. There was kind of a nod and a wink when they were told, ‘Don’t go over the Yalu, but we all know you’re going to.’”

Still, Aldrin was reluctant to admit where he shot down the MiG-15. If discovered that he was over China at the time, he would have been denied credit for the air-to-air victory. Fortunately, his secret was safe. “[T]here was no way to tell from the gun camera film what side of the river I’d been on, so the Air Force gave me an oak leaf cluster to go with the Distinguished Flying Cross I’d gotten for the first MiG,” Aldrin wrote. “This time I’d earned it.”

It is not clear who flew the two aircraft Aldrin shot down. At that stage of the war, North Korean and Chinese pilots were both flying MiG-15s. Chinese jets often sported North Korean markings, possibly to make U.N. pilots believe the North Korean air force was stronger than it was. In addition, Soviet pilots were secretly flying missions during the war, also in North Korean jets. They would even don North Korean uniforms to fool U.N. pilots during flybys. The U.S. military was aware that Soviets were present because of Russian chatter on the radio, yet neither side would publicly acknowledge the reality of the situation.

Perhaps the surest indicator of who was flying an enemy plane was the capability of the pilot. North Koreans were poorly trained and not as adept at air combat. Chinese pilots were better because they were trained by the Soviets. The best pilots were usually Russian since they had the most experience. Aldrin’s adversary had certainly demonstrated some skillful piloting, so it’s possible he was a Soviet pilot.

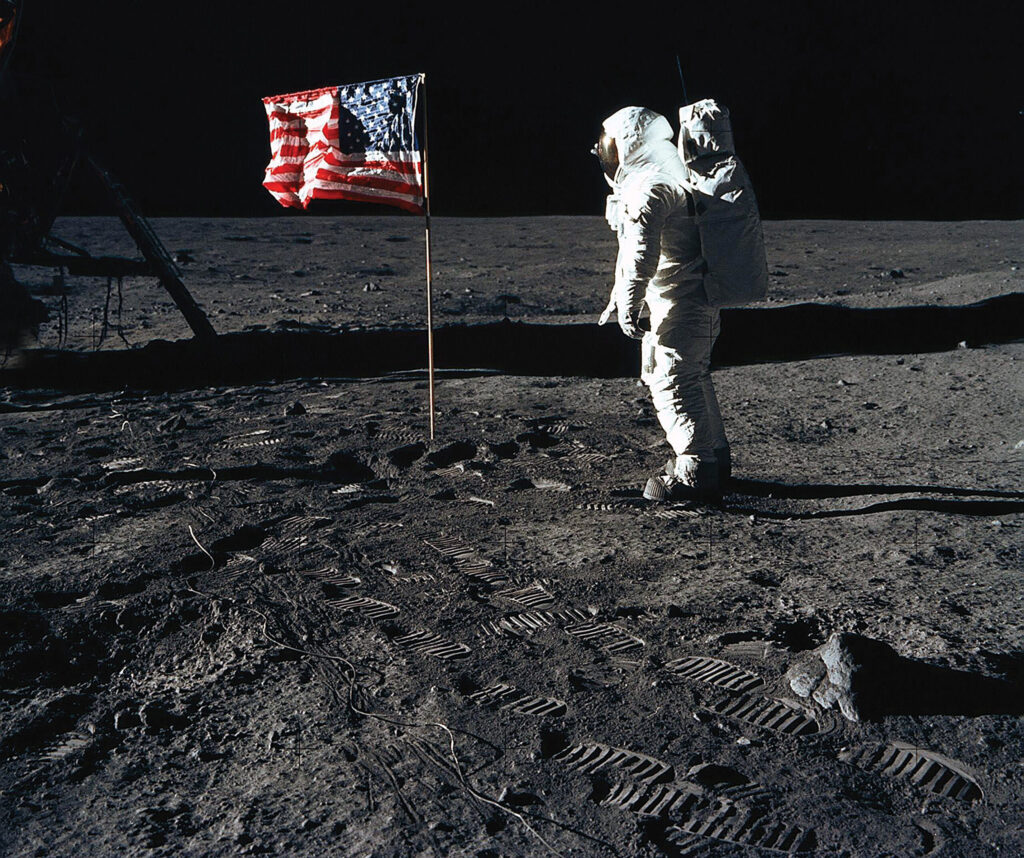

Aldrin finished his tour in Korea in December 1953 after the armistice had been signed. He had flown 66 combat missions. As a flight commander, he later flew F-100 Super Sabres equipped with nuclear weapons while stationed in West Germany. He then went back to school and earned a doctoral degree in astronautics from MIT in 1963, which opened the door for him to join NASA and the space program. In 1966, Aldrin and Jim Lovell rocketed into space on Gemini 12, a mission on which Aldrin made headlines again for a successful five-hour spacewalk—the longest on record at that point. Three years later, he was catapulted to worldwide fame when he joined Neil Armstrong for a stroll along the lunar surface during the historic Apollo 11 mission, an event viewed on television by an estimated 650 million people around the world.

Aldrin left NASA in 1971 and returned to the Air Force, retiring as a colonel in 1972. He received an honorary promotion to brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force in May 2023. In addition to his Distinguished Flying Cross and an Oak Leaf Cluster, Aldrin has an Air Force Distinguished Service Medal and Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a second DSM, three Air Medals, a Congressional Gold Medal, Presidential Medal of Freedom and the NASA Distinguished Service Medal, as well as many other honors and awards. At 93, Aldrin remains a strong advocate for space exploration, especially a manned mission to Mars. He has even proposed a special trajectory for such an expedition, using the gravity of Earth and Mars to send spacecraft to and from the planets. The procedure is known today as the Aldrin Cycler.

While exploring the dusty surface of Earth’s closest neighbor, Aldrin and Armstrong unveiled a plaque symbolizing the overall goal of the mission. Affixed to one of the legs of the lunar lander, the stainless-steel sign reads: “We came in peace for all mankind.” That was a stark contrast to his experience in Korea, where his objective was to stop communist aggression at all costs. In reality, though, both situations remained consistent with his overall mission in life. Talking to an interviewer in 2016, Aldrin said, “At age 17 at West Point, I took an oath to serve my country, and that has been the overriding purpose in all of my activities since then.”