Any mention of Soviet or Russian fighter aircraft immediately brings to mind one name: “MiG.” In fact, to most people the word is as synonymous with Russian fighter aircraft in much the name “Zero” once was for Japanese fighter aircraft. Of course, not all Russian fighters are MiGs, just as not all Japanese fighters were Zeroes, but those names became so prevalent that they became almost synonymous for their respective countries’ fighter planes.

“MiG” actually does not represent the name of a company or even an individual. It was the abbreviation of the names of two Soviet aircraft designers: Artyom Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, and their partnership ended up changing the face of military aviation — in the Cold War and beyond.

In Soviet Russia, Planes Build You

The aviation industry worked differently in the Soviet Union. Aircraft were not the products of companies. Instead, they were designed by engineers working at state-controlled Experimental Design Bureaus, or OKBs. Once an aircraft design was selected for production, it was assigned to a state-owned factory for mass production. The designers did not work for the factory, nor did they have anything to do with its management.

During the 1930s, Mikoyan and Gurevich were aeronautical engineers working at the OKB headed by Nicolai Polikarpov, who had created some of the most important Soviet aircraft of the 1930s, including the Po-2 trainer as well as the I-5, I-15 and I-16 fighter planes. However, Polikarpov fell out of favor during 1939 as a result of the failure of his I-180 fighter prototype, as well as a recent business trip to Germany he had been sent on in an attempt to acquire German aviation technology. While Polikarpov was in Germany, Gurevich presented a preliminary design proposal for a high-altitude fighter called the I-200. He set up his own design bureau in partnership with Mikoyan, whose elder brother was a senior official in Joseph Stalin’s political administration. They took many of Polikarpov’s staff along with them. Initially known as OKB-155, the new design bureau was subsequently renamed MiG, based upon the initials of the two leading engineers.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Before World War II: High Expectations

With war looming on the horizon in 1939, MiG’s I-200 became a high-priority project. It was to be a high-altitude fighter with a speed of 417 mph, a ceiling of 39,370 feet and a range of 621 miles. First flown in April 1940, the new aircraft exceeded 400 mph at over 22,000 feet and proved to be the fastest Soviet fighter ever made.

Unfortunately, it also had issues with maneuverability and stability. As a result, after only about 100 examples of the initial MiG-1 version were built, it was superseded by an improved version known as the MiG-3.

World War II: Wartime Weapon

Soviet fighter units were only just beginning to re-equip with the new Yak-1, LaGG-3 and MiG-3 fighters when Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. The MiG-3 was the fastest of the three and had the best high-altitude performance, but since the air war over Russia quickly developed into a mainly tactical conflict carried on at low to medium altitudes, the MiG-3 rarely had the opportunity to operate to its best advantage. The MiG-3 was also more difficult to handle than its counterparts and required experienced pilots, who were in short supply at that time.

However, the most important issue effecting MiG-3 production was its Mikulin engine, which was in demand for use in the Ilyushin Il-2 “Shturmovik” armored ground-attack aircraft.

“The Red Army needs the Il-2 as it needs air or bread,” Stalin himself declared. “I demand more!”

As a result, production of the MiG-3 was terminated in 1942, after 3,422 were built.

Nevertheless, the MiG-3 played a major role in the defense of Moscow during the air battles over that city in 1941 and 1942. Nearly half of the Soviet fighters deployed in the defense of Moscow were MiG-3s. Many were lost because they were frequently used during night interceptions, a mission for which the MiG-3 was neither designed nor equipped, and pilots flying them were untrained for that role.

Joining the Jet Set After World War II

Although MiG produced a few new designs during World War II, none of them advanced beyond the prototype stage. It was not until the end of the war that the design bureau finally came into its own through the creation of something totally new.

It was clear to the Soviets that the Red Air Force had fallen behind in jet aircraft technology, since the Germans, British and Americans already had operational jet fighters. Stalin demanded that his design bureaus to come up with jet fighters as quickly as possible. The competing design bureaus came up with different ways to meet that that need. On one hand, Alexander Yakovlev, who was vice minister of aviation in addition to heading his own aircraft design bureau, simply attached a German Junkers Jumo 004 jet engine onto his existing Yak-3 piston-engine fighter to create the Yak-15 jet fighter.

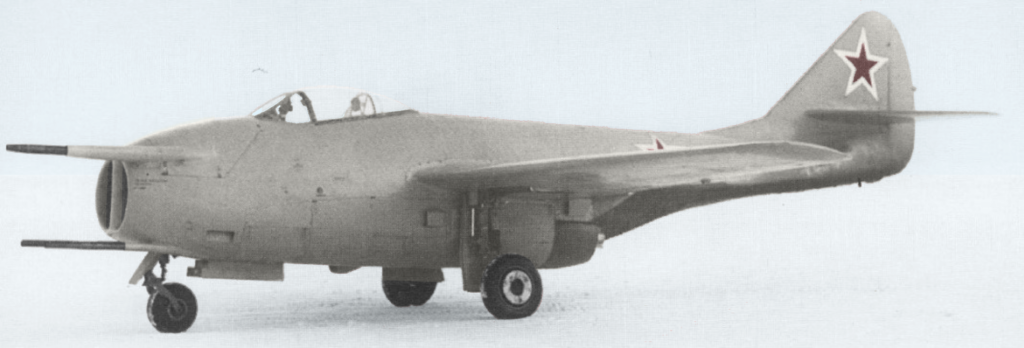

MiG, on the other hand, started from a clean sheet of paper to design an entirely new jet fighter. Powered by two BMW 003 turbojets, the resulting MiG-9 was a remarkable effort for a first-generation jet fighter created in such a very short time by engineers approaching entirely new technology for the first time.

Yak vs. MiG

Both the Yak-15 and MiG-9 were ready for flight testing on April 24, 1946. The order of the first flights was decided by a coin toss, resulting in the MiG-9 becoming the first Soviet jet fighter to fly. It was clear from the outset that the MiG-9 was the superior design. Both fighters ended up being ordered into production, but that coin toss became an omen, since, from that day on, MiG eclipsed Yak as the premier producer of Soviet fighter planes.

Nevertheless, the MiG-9 did exhibit a few issues. For one, firing the armament of two 23 mm cannons and one 37 mm cannon, the muzzles of which projected ahead of the air intake, could cause the engines to flame out. However, those faults were eventually rectified, and a total of 598 MiG-9s were built.

Recommended for you

Cold War: Beating the West

It was MiG’s next jet fighter that really made the world take notice. That story began in 1946, when the British government granted the Soviet Union permission to manufacture Rolls-Royce’s latest jet engine, the Nene. Reportedly, even Stalin was surprised at that lapse in judgement. Although the deal stipulated that the engine not be used for military purposes, the advent of the Cold War quickly abrogated that agreement.

So MiG was directed to initiate development of a new jet fighter powered by the Klimov RD-45, the Soviet version of the Nene. First flown on Dec. 30, 1947, the new MiG design also featured swept-wing technology acquired from Germany. Easily outperforming its straight-wing competitor, the Yak-19, the new fighter was ordered into production as the MiG-15. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the MiG-15 created as great a shock to Western aviators as the Japanese Zero had done a decade earlier. Armed with two 23 mm cannons and one 37 mm cannon, the MiG-15 had a top speed of 669 mph and could outclimb and outmaneuver most Western fighters, only the F-86 Sabre being able to meet it on equal terms.

During 1950, MiG introduced a refined version of the MiG-15, the MiG-17, which superseded it on the production line. Although too late for the Korean War, the MiG-17 became widely used by the Soviets as well as allies such as China and North Vietnam. Allegedly, some MiG-17s are still in active service with the North Korean air force. All told, about 28,000 MiG-15s and MiG-17s were built and used operationally by the air forces of no less than 36 different nations.

Cold War: Going Supersonic

First flown in 1952 and introduced into service in 1955, MiG’s next effort, the MiG-19, was the Soviet Union’s first supersonic jet fighter. Powered by a pair of Tumansky RD-9B turbojets generating 7,100 pounds of thrust, the MiG-19 had a top speed of Mach 1.35 and was a match for the USAF’s latest “century fighters” of the mid-1950s. Although allegedly difficult to fly, a total of 2,172 MiG-19s were build, not including about 4,500 examples manufactured under license in China. They were used by many satellite air forces, including that of North Vietnam.

The 1950s witnessed unprecedented improvements in aircraft performance. A replacement for the MiG-19 would be necessary if the Soviet air force were to maintain parity with the new generation of Mach 2 fighters such as the Phantom II, F-8 Crusader, Mirage, English Electric Lightning, F-104 Starfighter and F-5 Freedom Fighter.

On June 16, 1955, MiG flew the first prototype of a new jet fighter that could match its Western opponents in nearly every respect, the MiG-21. Combining small, mid-mounted delta wings with a conventional tail, the MiG-21 looked like no other jet fighter in the world and eventually became almost as ubiquitous as the AK-47 assault rifle. Powered by a single Tumansky jet engine producing, depending on the variant, from about 7,000 to 14,000 pounds of thrust, the MiG-21 had a top speed of Mach 2.05 and was armed with a single 23 mm cannon and either four K-13 or eight R-60 air-to-air missiles. With a total of 13,896 produced, more MiG-21s have been built than any other Mach 2 fighter, and it has been used by the air forces of no fewer than 44 different nations. Not least among those was North Vietnam, where the MiG-21 became a particular bane of American flyers operating over their airspace.

Cold War: Mach 3 Fighters

During the early 1960s, one aircraft that the MiG-21 was clearly not capable of intercepting was the North American B-70, a Mach 3 strategic bomber under development for the U.S. Air Force. Although the B-70 program eventually was canceled after only two prototypes were flown, the Soviets took the threat seriously enough to order MiG to develop an interceptor specifically to counter it. The result was the MiG-25, a truly gargantuan single-seat fighter plane that, at nearly 81,000 pounds and more than 82 feet, was larger than many World War II strategic bombers.

Powered by a pair of Tumansky R-15B jets producing 22,500 pounds of thrust each, the MiG-25 had a speed of Mach 2.85 and a ceiling of over 67,000 feet, which it could attain nine minutes. Some MiG-25s were also completed as high-speed reconnaissance aircraft.

Despite the cancellation of the B-70, the MiG-25 was perceived as a significant threat to the CIA’s Lockheed SR-71 strategic reconnaissance aircraft. A total of 1,186 MiG-25s were produced, not including an additional 519 of an improved version called the MiG-31, introduced during the 1980s. The MiG-25 is said to have been the last design that Mikhail Gurevich worked on before he retired.

Cold War: Flexible Fighters in the 1960s and 1970s

Effective as the MiG-21 proved, it did have limitations. By the early 1960s, the Soviets required a more versatile aircraft that could double as an air-to-air fighter or a fighter-bomber. The new fighter needed increased armament, electronic equipment and fuel for greater range. Since the MiG-21’s nose air intake limited the size of the radar sensors that could be installed, the new aircraft needed side air intakes. The newest MiG also ended up featuring another first for MiG: variable geometry swing-wings to optimize performance in a variety of flight regimes.

First flown in 1967, the MiG-23 entered service in 1970. It was produced in a variety of versions, including an armored ground-attack variant called the MiG-27. A total of 6,122 MiG 23s and MiG-27s were manufactured and have been used by a total of no less than 37 different air forces. Artyom Mikoyan died in 1969, so the MiG-23 was probably the last MiG design to which he contributed.

Despite the absence of its two founders, the MiG design bureau continued to develop new cutting-edge fighters. First flown in 1977, their next new product, the MiG-29, was clearly intended to counter the latest generation of U.S. fighters, principally the F-15 eagle, F-16 Falcon and F-18 Hornet. Entering service in 1982, despite some structural issues, over 1,600 MiG-29s have been manufactured. They have been used by over 30 countries.

MiGs After the USSR

In 1978, MiG became restyled “Mikoyan.” After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the OKB was transformed into a corporation and merged with the Moscow Aviation Production Association. During the 1990s, they developed a new fifth-generation jet fighter, initially known as the MiG-1.42 and, subsequently, the MiG-1.44.

However, the firm does not appear to have adapted well to the new capitalist methods, since, after a decade of work resulting in only one flying prototype, development of the MiG-1.44 appears to have been canceled. At present, the only program in which Mikoyan appears to be engaged is the development of an improved MiG-29 known as the MiG-35.

In recent years, MiG’s place as the leading developer of Russian fighters appears to have been usurped by rival Sukhoi. Nevertheless, the legacy of MiG and their place in aviation history rests secure on well over half a century at the top of one of aviation’s most competitive hierarchies: the producers of high-performance jet fighters.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.