Accounts of Benjamin Franklin’s years in Paris describe a celebrated bon vivant, wily diplomat and aging lion prowling on behalf of the cause of liberty. None of these labels negates any other, but in focusing on them chroniclers almost always leave out the clandestine aspects of Franklin’s activities abroad. If the popular bespectacled grandfatherly image of Franklin, a genial gentleman given to aphorisms and electrical experimentation, seems at odds with the intricacies of espionage, all the better. Spycraft is never more effective than when practitioners seem unlikely to be engaged in it.

Arriving in Paris in December 1776, Franklin remained in the French capital until 1785. Operating from a well-appointed residence in Passy, a wealthy Parisian suburb, he included in his multifarious efforts on behalf of the American project the printing of official documents as well as surreptitious production of propaganda and misinformation.

SPYmaster Franklin

Franklin, of course, was no stranger to intrigue. As one of the original members of the Committee of Secret Correspondence, established in 1776 by the Continental Congress to communicate with sympathetic Britons and other Europeans, he was an early and active participant in the emerging nation’s first spy organization. And he had done clandestine printing. In Philadelphia he produced leaflets, folded to hold tobacco, incorporating a surreptitious message aimed at Hessian troops. The leaflets, distributed among the Germans’ camps, promised a prosperous and peaceful life in the new nation to mercenaries who deserted working for the British side.

There is also reason to credit Franklin with the mysterious document known as the “Sale of the Hessians Letter.” Dated Feb. 18, 1777, the purported communique ostensibly is from a fictitious Count de Schaumbergh in Germany to an equally fictitious Baron Hohendorf, supposedly the commander of Hessian troops in North America. The message, in French, requests that Hohendorf see to it that more Hessians die in combat or from denial of medical treatment to enhance the flow of mercenary revenue from Britain.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

FRANKLIN: PASSY FIST

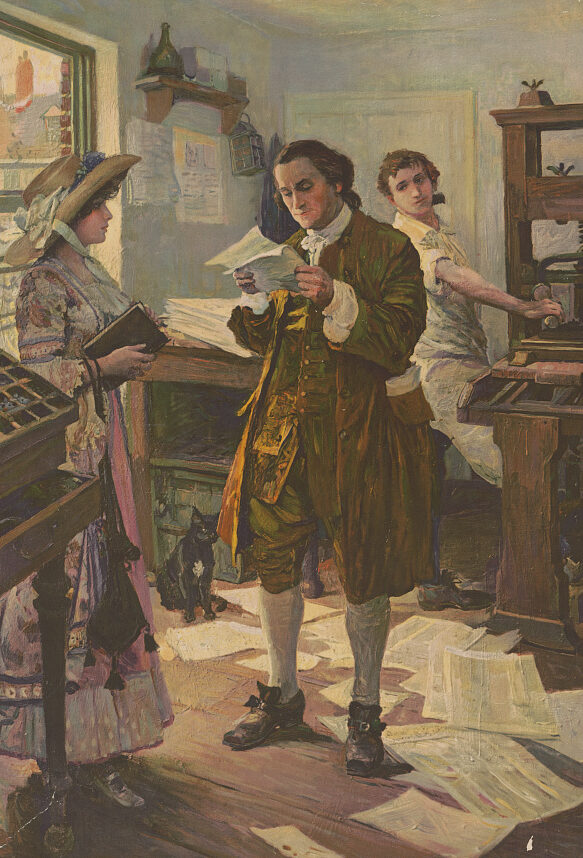

Franklin, upon setting up housekeeping at Passy, quickly acquired a printing press and related equipment. Years of experience as a printer and publisher had schooled him not only in the skills those roles demanded but also the power of the printed word. Parisian print shops would have eagerly turned out whatever documents the colonial envoy required, but Franklin, who apprenticed as a printer in youth and mastered the trade, insisted on overseeing the printing himself and soon had brought his young grandson Benjamin “Benny” Franklin Bache into the operation.

His press, one of the finest available, was largely outfitted by the Fournier family’s type foundry in Paris. In addition to standard typefaces, the Fourniers supplied a typeface — Le Franklin— designed and cast for his exclusive use. Franklin also acquired type from British foundry Caslon, buying typefaces through a front company in the Netherlands. So that he could create his own typefaces, he also outfitted his shop at Passy with a small foundry, and for a while employed a multilingual compositor.

Franklin’s insistence on having his own press arose in part from his duty to produce passport blanks, loan certificates and other sensitive official documents. Maintaining end-to-end control over these items discouraged attempts at forgery. However, he also used his press and his skills to publish witty satirical essays he composed in French and English. These Bagatelles, as he called them, numbered a dozen or so, and went to close friends. The best known may be “A Dialogue Between Franklin and the Gout,” followed by the “Morals of Chess.”

Sneak Peek

In one notable instance, Franklin did rely on a French printer. In 1783, he arranged through a nobleman, Louis-Alexandre de La Rochefoucauld, to have the 13 American colonies’ constitutions translated into French for printing and distribution in his host country. In addition to offering French officials a preview of what the U.S. Constitution would likely include, the gesture marked an early appearance by the Great Seal of the United States, prominent on the volume’s title page. Since the document was to be circulated openly, Franklin went through official channels and hired Paris printer M. Pirres to print the edition. In June 1783, Franklin had the finished copies bound in an assortment of lavish calfskin and Moroccan leather covers. The first circulated went to King Louis XVI and his family.

The gesture seems to have gone over well. In a Dec. 25, 1783, letter to Thomas Mifflin, president of Congress, Franklin wrote, “It has been well taken, and has afforded Matter of Surprise to many, who had conceived mean Ideas of the State of Civilization in America, and could not have expected so much political Knowledge and Sagacity had existed in our Wildernesses. And from all Parts I have the satisfaction to hear, that our Constitutions in general are much admired. I am persuaded that this Step will not only tend to promote the Emigration to our Country of substantial People from all Parts of Europe by the numerous Copies I shall disperse, but will facilitate our future Treaties with foreign Courts, who could not before know what kind of Government and People they had to treat with.”

Revolutionary Fake News

Franklin’s masterpiece of disinformation and covert influence came late in the Revolution, when he forged a newspaper supplement whose contents effectively but falsely alleged that Native Americans, at the British army’s behest, committed atrocities against American rebels. The 1782 forgery represented itself as “A Supplement to The Boston Independent Chronicle.”

Franklin’s fake, measuring 14 5/16 inches by 9 1/8 inches, was a broadsheet in size and design. Posing as an addendum to a legitimate edition of an actual and widely read newspaper, the bogus two-pager incorporated phony real estate advertisements and a notice of a “stolen or stray Bay Horse.” These quotidian items, staples of the form, lent credibility to the main content.

Franklin also indulged in literary trickery intended to enhance his creation’s credibility. The field report, ostensibly written by “Captain Samuel Gerrish” of the New England militia, incorporates a letter by British agent James Craufurd to Colonel Haldimand, governor of Canada, detailing the Indian atrocity. Craufurd, purported to have been captured by Patriot troops, describes the scalps of men, women and children taken by Native American allies of the Crown. In an appropriately dispassionate military voice, the letter says that goods captured included “eight Packs of Scalps, cured, dried, hooped and painted, with all the Indian triumphal Marks.”

The Crauford missive also presents what purports to be a transcribed translation of a Native American speech paying tribute to King George and presenting the monarch with the grisly cargo. The three narratives’ specificity bolsters one another’s believability, suggesting this may not have been the first such macabre tribute the king had received.

The false story’s recitation of gruesome details sought to attract, repulse and outrage European readers and thereby influence peace talks with Britain, then entering a crucial phase. In an aside in the “Gerrish” letter Franklin introduces another character, a “Lieutenant Fitzgerald.” Granted leave to return to Ireland on a family matter, the fictional Fitzgerald has volunteered to detour to London with the scalps and “… hang them all up in some dark Night on the Trees in St. James’s Park, where they could be seen from the King and Queen’s Palaces in the Morning …”

In addition to his canny choice of format, Franklin took care to salt his fiction with familiar references. Indirectly invoking the French and Indian War of the 1750s, he had his characters contrast “Indian savagery” and the code of “civilized warfare,” echoing contemporaneous news reports and post-war memoirs. The passage also fit European assumptions regarding North America as a wild and untamed land.

As with all good propaganda and disinformation, the material played to existing beliefs and added accurate details. In composing his falsehoods Franklin ignored his own enlightened and moderate view of Native Americans, which he expressed in “Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America” (1784), also printed at Passy.

The flip side of the broadsheet was a letter purportedly written by American naval commander John Paul Jones to British Adm. Sir Joseph Yorke, then serving as ambassador at the Hague. “Jones” was protesting treatment of American seamen imprisoned by the British for piracy, a cause genuinely close to Franklin’s heart. At least some of the passports that Franklin printed were slipped to sailors who had escaped British prisons and reached France. And Franklin had funded a London operative smuggling escaped seaman out of England. A one-sided early run of the fake broadsheet, sans the “Jones” letter, was printed but does not appear to have been circulated.

“A pirate makes war for the sake of rapine. This is not the kind of war I am engaged in against England,” “Jones” writes to “Yorke.” “Our’s is a war in defence of liberty … the most just of all wars; and of our properties, which your nation would have taken from us, without our consent, in violation of our rights, and by an armed force. Yours, therefore, is a war of rapine; of course, a piratical war: and those who approve of it, and are engaged in it, more justly deserve the name of pirates, which you bestow on me.”

Getting the fake news out

Franklin did not personally distribute the Chronicle forgery but relied on credible but unsuspecting acquaintances to circulate it. Ideally, his agents would get the supplement to editors at trusted publications whose reputations would enhance the report’s credibility. Franklin sent copies to John Adams, now an envoy in Amsterdam, and John Jay, stationed in Madrid. Additional copies went to an American operative, Charles William Frédéric Dumas, a German national of Swiss parentage and trusted friend of Franklin’s who operated in Amsterdam, and James Hutton, a prominent congregant of the Moravian church in London.

Recommended for you

In an April 22, 1782, letter to Adams sent with a copy of the fake broadsheet, Franklin strongly hinted at the document’s true nature.

“I send enclosed a paper, of the Veracity of which I have some doubt, as to the Form, but none as to the Substance, for I believe the Number of People actually scalp’d in this murdering war by the Indians to exceed what is mentioned in invoice,” he wrote. “These being substantial Truths the Form is to be considered as Paper and Packthread. If it were republish’d in England it might make them a little asham’d of themselves.”

A May 3,1782, letter to Dumas also suggests the Gerrish report’s veracity and purpose.

“Enclosed I send you a few copies of a paper that places in a striking light, the English barbarities in America, particularly those committed by the savages at their instigation,” Franklin wrote. “The route may perhaps not be genuine, but the substanceis truth; the number of our people of all kinds and ages, murdered and scalped by them being known to exceed that of the invoice. Make any use of them you may think proper to shame your Anglomanes, but do not let it be known through what hands they come.”

Dumas was a particularly good choice as a collaborator. Not only had he gained experience in clandestine matters at the start of the Revolution, creating the first diplomatic cipher used by the Continental Congress, but previously planted stories in Dutch papers, such as the popular Gazette de Leyde in Leiden, Netherlands.

Too Good for his Own Good

As a typesetting propagandist and psychological warfare operative, Franklin was both meticulous and sloppy. He took care to give his fake broadsheet a genuine edition number — “Numb. 705,” issued on March 12, 1782 — and to refer in it to Nathaniel Willis, a well-known Boston newspaper editor. But the editor and the actual paper involved were not connected. Franklin’s forgery was supposedly the Boston Chronicle; Willisedited the Boston-based Independent Chronicle and the Universal Advertiser. Whether this mix-up was intentional or inadvertent is unknown.

Franklin also was over-enthusiastic with typefaces. As a matter of style and economics, a newspaper of the day would have kept font changes to a minimum in a given issue, but in laying out his fake broadsheet Franklin employed a variety of faces and fonts clearly beyond the means of even a prominent Boston newspaper. He also used the custom typeface the Fourniers had created for him. No one apparently blinked at the jumble of styles, nor noticed that the sheet used the faces he had employed in composing the Bagatellesand official documents.

Franklin’s prose also may have been too clever by half. British parliamentarian and noted author Horace Walpole, reading the forgery as reprinted in London’s Public Advertiser on Sept. 27, 1782, grew skeptical of the “Jones” letter. “Dr Franklin himself I should think was the author,” Walpole wrote to a friend. “It is certainly written by a first-rate pen, and not by a common man-of-war…The ‘Royal George’ is out of luck!”

Walpole was not alone. The editor of the London Public Advertiser called the letter to Yorke a work of “contemptuous insolence” and “the Production of some audacious Rebel.”

TRUE LIES

Misinformation’s impact is difficult to quantify, but the success of Franklin’s fakery shows in its durability. THe “Gerrish” atrocities report resurfaced multiple times, notable in the years preceding the War of 1812. The Reporter, whose circulation included Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, ran the fake report on its front page in December 1811, headlined, “British Warfare.” The editors’ introduction read, “At a time when it is notorious that English agents are actively employed in exciting the savages to commence war on the citizens of our western frontier, we consider it a duty we owe our country to give a place to the following account of some of the atrocities committed by the Indians in this state during the revolutionary war, to which they were excited by the ministry, of that idiot king, who we hope will live to atone, in some degree, in his own person, for part of the evils with which he has so long afflicted mankind.”

According to one historian, the Gerrish story was reprinted no less than 35 times with many periodicals simply copying it from other publications. To date, the earliest public confirmation of the forgery was by the State Gazette in Trenton, New Jersey, in that paper’s Oct. 4, 1854, issue.

Secrets he kept till his death

Franklin, who died in 1790, never commented publicly on his clandestine publishing career and left few clues to the extent of his disinformation activities. His grandson downplayed the press at Passy, writing, “Notwithstanding Dr Franklin’s various and important occupations, he occasionally amused himself in composing and printing, by means of a small set of types and press he had in the house, several of his light essays, bagatelles, or jeux d’esprit written chiefly for the amusement of his intimate friends.”

The truth of Franklin’s involvement and extent of his printing operations in France emerged in 1914 when Luther S. Livingston, a bibliophile and scholar, brought out “Franklin and his Press at Passy.” In that volume, published by the Grolier Club in a limited edition of 300, Livingston brought together the document’s text, technical aspects, letters and other evidence to paint a clear picture of not only Franklin’s involvement but also his intent.

“The sheet was circulated with a political purpose which was quite foreign to the light-hearted, philosophical or amusing ‘Bagatelles’ already enumerated, and though it has been called a ‘bagatelle’ by modern Franklin editors, I have not included it in my description of those pieces,” Livingston wrote.

Livingston had it right. The bogus supplement was neither satire nor whimsy. Unfamiliar with espionage jargon, he and other commenters to this day invariably call the spurious Revolutionary War-era broadsheet a “hoax.” In his Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Franklin, Carl van Doren labeled the escapade an instance of “gruesome propaganda.” Today Benjamin Franklin’s imaginative effort would be called “fake news.”

Henry R. Schlesinger is an author and journalist with a specialty in espionage. His latest book, Honey Trapped is available through The History Press in the U.K. and Rare Bird in the U.S.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.