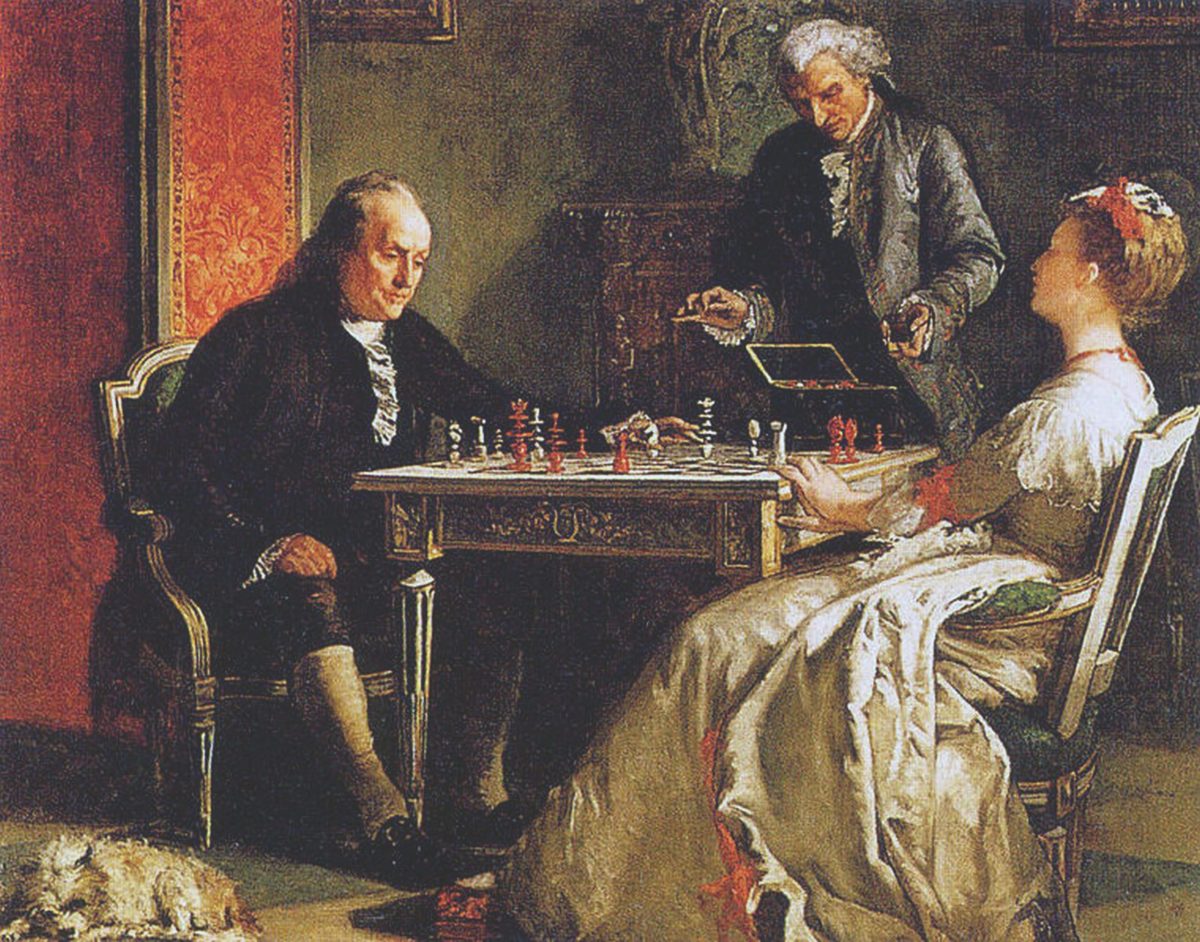

One evening in the fall of 1777, Benjamin Franklin was sitting at the chess table, deep in a game with close friend and neighbor Louis-Guillaume Le Veillard. Le Veillard was the mayor of Passy, the elegant Parisian suburb where Franklin resided. The Sage of Philadelphia had arrived the year before, commissioned by Congress to negotiate an alliance with France, but seemed to spend more time absorbed in pastimes like the one before him than engaged in diplomacy.

The players had an audience of one. As was her habit, Franklin’s mistress, Anne Louise Brillon de Jouy, was watching the game from her enclosed bathtub, whose wooden cover preserved her modesty. The play lasted into the small hours. Immersed so long, Brillon’s skin turned prunish, later prompting her lover to apologize by post. “I’m afraid that we may have made you very uncomfortable by keeping you so long in the bath,” Franklin wrote. “Never again will I consent to start a chess game with the neighbor in your bathing room. Can you forgive me this indiscretion?”

“No, my good papa, you did not do me any ill yesterday,” Madame Brillon replied. “I get so much pleasure from seeing you that it made up for the little fatigue of having come out of the bath a little too late.”

The game of revolutionaries

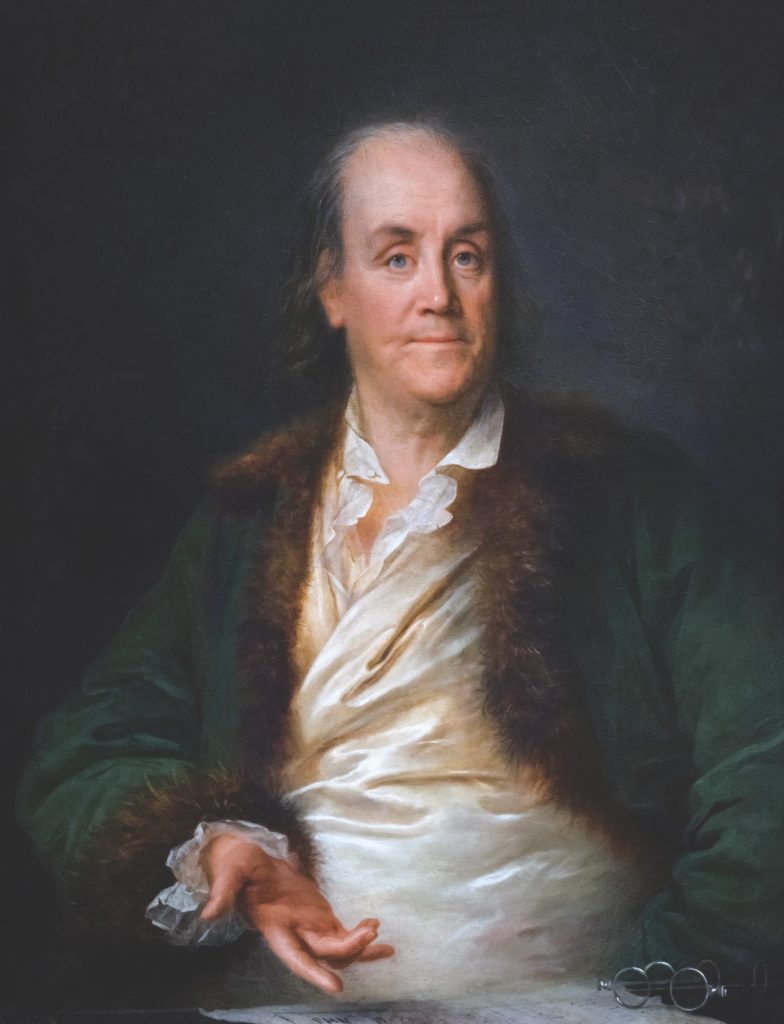

In his lifelong enthusiasm for chess, Benjamin Franklin had company among his fellow revolutionaries. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison competed avidly in four-hour games. In a pen-and-ink sketch artist John Trumbull showed George Washington and Israel Putnam at the board. But Franklin stood head and shoulders above them all, not only as a player of the game but as a writer on the subject. The practice and discipline that chess instilled in him helped Franklin to achieve diplomatic triumph during the Revolutionary War. Far from being a distraction, he insisted, the time and energy that he devoted to the game were crucial to moving America along the path to independence.

Franklin published numerous essays on his favorite pastime, dating to his days in the 1730s as the young proprietor of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Notably, in his Autobiography he mentions a friend from that period with whom he was studying Italian, a fellow who “used often to tempt me to play chess.” Franklin agreed to play provided “the victor in every game should have a right to impose a task, either parts of the grammar, to be got by heart, or in translations.” He and his companion being well-matched on the board, Franklin drily remarked, “we thus beat one another into that language.” This was classic Franklin—mixing enterprise with pleasure, play with self-improvement.

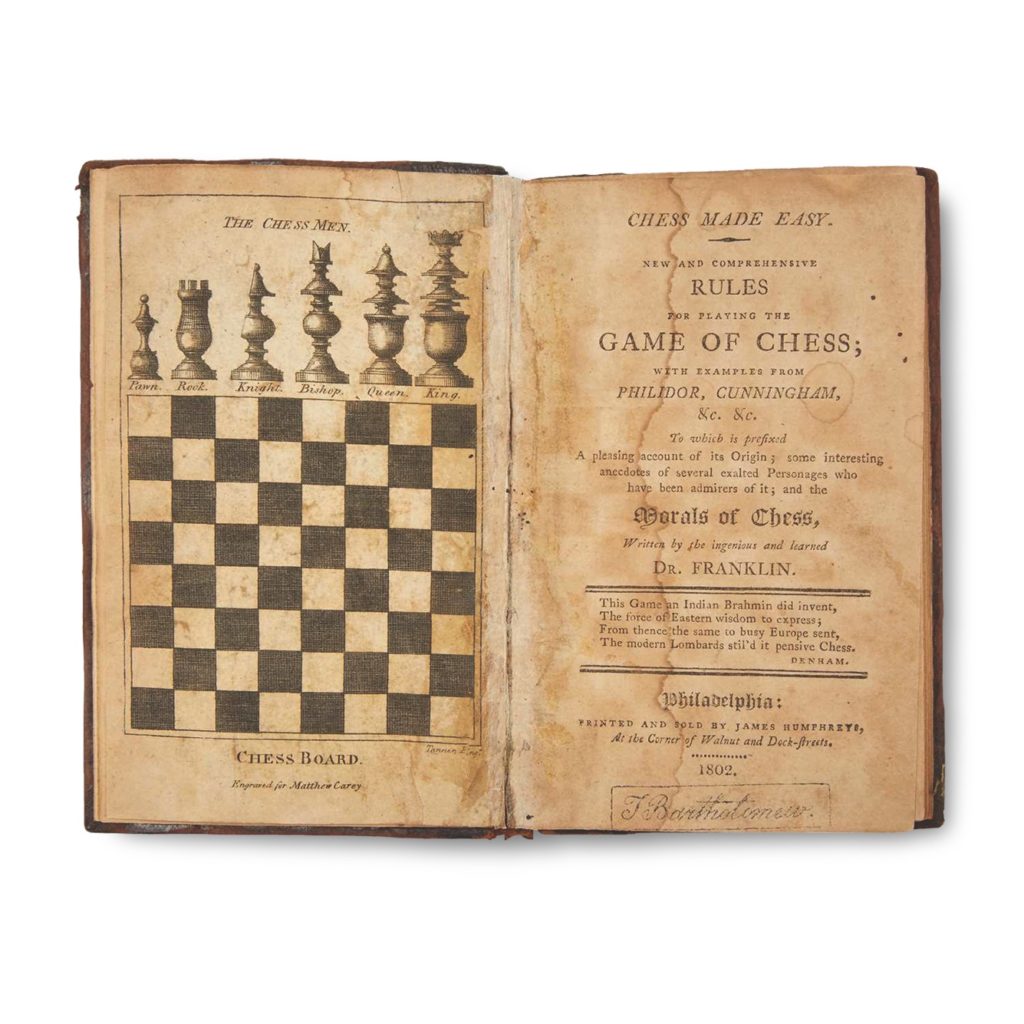

Although Franklin’s Autobiography contained his most widely known references to chess, his 1779 essay “The Morals of Chess” is by far his most revealing. Before he published this brief, humorous “bagatelle,” or trifling amusement, no American had brought out a book or article on the subject. No copies of its original French imprint are thought to have survived, but a 1786 reprint in the Columbian Magazine introduced that essay to American readers. Franklin began his discourse by sketching the game’s origins and evolution, likening its influence to that of civilization itself. The game’s origins, he wrote, lay “beyond the memory of history,” having formed “the amusement of all the civilized nations of Asia, the Persians, the Indians, and the Chinese. Europe has had it above 1000 years; the Spaniards have spread it over their part of America, and it begins lately to make its appearance in these northern states.” While acknowledging the antiquity of chess, he insisted, “[t]hose…who have leisure for such diversions, cannot find one that is more innocent; and the following piece, written with a view to correct (among a few young friends) some little improprieties in the practice of it, shows at the same time that it may, in its effects on the mind, be not merely innocent, but advantageous, to the vanquished as well as to the victor.”

Franklin is rightly considered American chess literature’s founding father, but his willingness, even eagerness, to avail himself of the board amid often tense treaty negotiations at Versailles tells its own story. When Franklin described the game as “the image of human life, and particularly of war,” he was commenting in deadly earnest. And though he loved chess and played it constantly, for him the game was never “merely an idle amusement.” Chess, he insisted, inculcated in enthusiasts valuable habits “useful in the course of human life.” These included “foresight,” “circumspection,” “caution,” and, crucially, “the habit of not being discouraged by present bad appearances in the state of our affairs.” That chess could furnish such an education was only natural, he believed. “For life,” he wrote, “is a kind of chess, in which we have often points to gain, and competitors and adversaries to contend with, and competitors or events, that are, in some degree, the effects of prudence or the want of it.”

networking across the chessboard

Franklin dedicated the original “La Morale des Échecs” to Madame Brillon, circulating copies of the work among his close-knit circle in France. These chess-playing friends, neighbors, and enhancers of his diplomacy included the polymath Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg, who in the 1760s had introduced French readers to Franklin’s experiments, electrifying a cult of personality that developed around the American scientist. Another ally was Louis-Guillaume Le Veillard, with whom Franklin jousted on the square board beneath Madame Brillon’s eye.

But none of these allies made the same impact as Franklin’s formidable network of female friends and supporters. French society was staunchly patriarchal, but aristocratic women like Madame Brillon wielded power both in the salon and the boudoir—in ironic contrast to the domesticated ideals of womanhood prevailing in revolutionary America. Even before the Revolution, Franklin was leveraging his relationships for diplomatic ends. In London, as late as 1774 and despite having lost official favor as Pennsylvania’s overseas representative, he continued to pursue reconciliation between the Crown and his fellow rebellious colonists.

Franklin described how a colleague at the Royal Society told him of “a certain Lady who had a desire of playing with me at Chess, fancying she could beat me.” Franklin duly visited the woman, whose name was Howe, at her home and played a few games. Finding Madame Howe “of very sensible Conversation and pleasing Behaviour,” Franklin agreed to meet for another round of chess. He claimed to experience “not the least Apprehension that any political Business could have any Connection with this new Acquaintance.” As it turned out, their chess playing was a prelude for communicating with her brother, British Admiral Lord Richard Howe, who shared Franklin’s hopes for a peaceful outcome. Those talks came to nothing, however, and upon the outbreak of war, the Royal Navy dispatched Admiral Howe to blockade the American coast. Franklin remembered Lady Caroline Howe fondly, but never said who won their games.

With the cunning of a master chess player, Franklin grasped the power of appearance in an image-obsessed world. Arriving in France in December 1776, he presented himself as a rustic philosopher, a colonial rube jarringly out of place amid the sophistication at Versailles. “Figure me in your mind as jolly as formerly, only a few years older; being very plainly dress’d wearing my thin gray strait hair, that peeps out from under my only coiffure, a fine Fur cap, which comes down from my forehead almost to my spectacles,” he wrote an old flame shortly after his arrival. “Think how this must appear among the powder’d heads of Paris!” The French adored this incarnation of Franklin, who rode his notoriety to become an unlikely sex symbol. He cultivated multiple intense friendships with his female admirers, including the chess-loving Madame Brillon, four decades his junior. The widower described his married companion as “a lady of most respectable character,” whom he chided for being too demure. In return, she doted on “my dear papa,” and gave herself to public displays of affection, including sitting in Franklin’s lap and kissing his bald head.

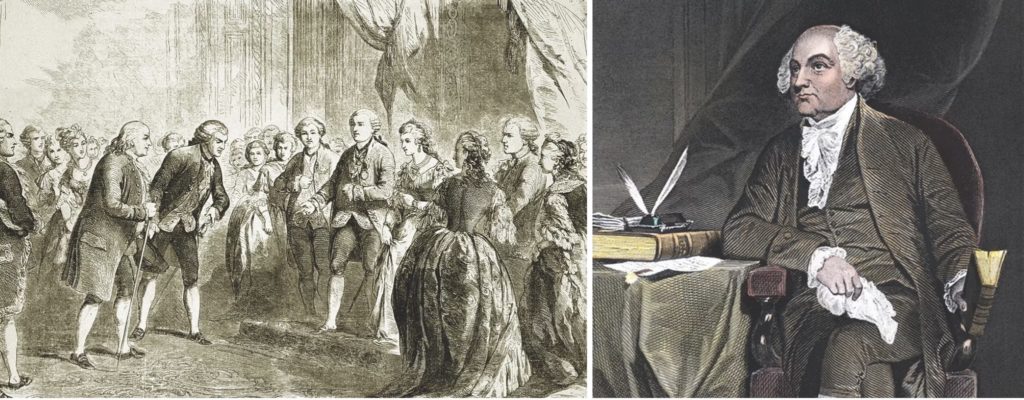

adams does not approve

Franklin’s tightly buttonedfellow diplomat John Adams could hardly have been less suited for the delicacy of their mission. Franklin’s dalliance with Madame Brillon, not to mention French manners in general, perturbed the unrelenting New Englander. It was bad enough that Adams could not understand his hosts’ language—worse, he did not even play chess.

Conceding that Brillon was “one of the most beautiful women of France,” Adams dismissed her husband as “a rough kind of country squire.” The Brillons noticeably kept company with a “very plain and clumsy woman,” he grouched, to which Franklin matter-of-factly commented that the lady was Monsieur Brillon’s mistress. “I was astonished that these people could live together in such apparent friendship and indeed without cutting each other’s throats,” Adams blustered. “But I did not know the world.”

Still bristling some 17 years after Franklin’s death, Adams related a scandalous anecdote to Mercy Otis Warren, the pioneering female historian. At a banquet in France, “in company with Archbishops and Bishops,” an engraving was handed around the table to “much diversion,” Adams told Warren. Eventually, a pair of smirking French abbés showed Adams the titillating image.

“With all the skill of the finest artists in Paris, America was represented as a Virgin naked,” Adams said. “And the grand Franklin, with his bald head, with his few long scattering straight hairs, in the Act of debauching her behind her back. Can you imagine any Ridicule more exquisite than this both upon America and Franklin?”

To the puritanical Adams, such displays of decadence only confirmed his worst fears regarding France, as well as his fears regarding Franklin.

The louche persona Franklin inhabited so enthusiastically, and which Adams so despised actually accounted for the former’s enviable success as a diplomat. With independence in the balance, Franklin seemed to Adams to be frittering away time and goodwill gossiping and playing chess with French nobles. Adams recorded his profound dismay in a 1778 diary entry. “The Life of Dr. Franklin was a Scene of continual dissipation,” he wrote.

The contrast between the two men was near complete. Not only was Franklin given to breakfasting late—Adams habitually rose at five—but the older man spent his afternoons entertaining visitors over tea, and evenings “hearing the Ladies sing and play upon their Piano Fortes…and in various Games as Cards, Chess, Backgammon, &c. &c.” As Adams noted, however, “Mr. Franklin never play’d at any Thing but Chess or Checquers.”

Leisure pursuits exerted no pull on Adams, anxious always to get down to business. The New Englander believed France to be stalling efforts by the United States to activate an alliance, finally formalized in February 1778. He began pressuring French officials for greater economic and military commitment. His targets included France’s foreign minister, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, who in the summer of 1780 responded to Adams’s hectoring by issuing an exasperated response. “The King,” he wrote, “did not stand in need of your solicitations to direct his attentions to the interests of the United States.”

Scrambling to the rescue, Franklin kowtowed to Vergennes, expertly displaying a sense of where the game was going and gently pressuring it into a fresh direction. “Mr. Adams…thinks, as he tells me himself, that America has been too free in expressions of gratitude to France,” Franklin told the French noble. “I apprehend that he mistakes his ground, and that this Court is to be treated with decency and delicacy. The King, a young and virtuous prince, has, I am persuaded, a pleasure in reflecting on the generous benevolence of the action in assisting an oppressed people, and proposes it is as a part of the glory of his reign. I think it right to increase this pleasure by our thankful acknowledgments, and that such an expression of gratitude is not only our duty, but our interest.”

master of diplomacy

In life as on the board seldom making a bad move, Franklin was a master of tact and diplomacy, even while stabbing a colleague in the back. In chess terms, Adams was a blunderer; as Franklin put it, despite certain admirable qualities his fellow diplomat was “sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses.”

Reflections of Franklin’s relationship with the testy Adams abounded in “The Morals of Chess,” in whose columns Franklin rebuked players who interrupted their opponents. “If your adversary is long in playing, you ought not to hurry him, or express any uneasiness at his delay,” he wrote. “You should not sing, nor whistle, nor look at your watch, nor take up a book to read, nor make a tapping with your feet on the floor, or with your fingers on the table, nor do anything that may disturb his attention. For all these things displease. And they do not show your skill in playing, but [only] your craftiness or rudeness.”

Had Adams only been seasoned at playing the literal game, he might have had the wit to take greater care figuratively to survey “the whole chess-board, or scene of action, the relations of the several pieces and situations, [and] the dangers they are respectively exposed to,” and avoid causing near-disaster. Instead, his blundering redounded in Franklin’s favor. Eschewing Adams’s battering-ram approach, Franklin’s chess-conditioned crisis diplomacy secured its reward. At Vergennes’s insistence, Franklin effectively assumed the role of sole diplomatic voice for the United States at Versailles.

With Franklin as with chess, appearances did not always match reality. Though emphasizing good sportsmanship in “The Morals of Chess,” he was in fact a poor loser, soon tiring of opponents, disarranging their pieces if they left the room, and frequently drumming his fingers on the table. Thanks as much to a competitive temperament as to a razor-sharp mind, Franklin is said to have won more often than he lost—though, since none of his games was formally recorded, his prowess remains a mystery. In Paris, he frequented the Café de la Regence, where the day’s best players—including legendary French master François-André Danican Philidor—plied their skills, likely sending him home to Passy in defeat.

the mechanical turk

But without doubt, Franklin’s most famous loss came at the hands of an opponent ostensibly not even human. In 1783, while negotiating the terms of independence from Great Britain, Franklin played the Mechanical Turk, a remarkable specimen of automaton then touring Europe. Anticipating the super-intelligence of modern chess machines, the Turk was—as Franklin deduced—an elaborate hoax. In its base hid a talented human player, who, using a complex array of pulleys and magnets, manipulated the chess pieces above him.

The Turk’s operators left no detail to chance, even redirecting smoke from the hidden player’s candle through the effigy’s pipe. The automaton’s Austrian designer, Wolfgang von Kempelen, surely merited the approval lavished on his creation—which defeated Benjamin Franklin.

The more Savage game

Returning to America in 1785, Franklin served in 1787 as a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention, burnishing his distinguished career by becoming the only founder to sign not only the Declaration of Independence, but the Franco-American Treaty of Alliance, the Treaty of Paris, and the United States Constitution. Regarding the last, a woman encountering Franklin on the steps of Independence Hall famously demanded, “Well, Doctor, what have we got, a republic or a monarchy?”

“A republic,” he replied, “if you can keep it.”

Franklin’s tone of wariness expressed volumes. Embroiled in the infighting surrounding the fate of the young republic, he had begun to question the validity of his lifelong conviction that politics was a game of logic.

“We must not expect that a new government may be formed, as a game of chess may be played, by a skillful hand, without a fault,” he confided in a letter to the former mayor of Passy, his friend Le Veillard. “The players of our game are so many, their ideas so different, their prejudices so strong and so various, and their particular interests independent of the general seeming so opposite, that not a move can be made that is not contested; the numerous objections confound the understanding; the wisest must agree to some unreasonable things, that reasonable ones of more consequence may be obtained, and thus chance has its share in many of the determinations, so that the play is more like tric-trac with a game of dice.”

Having left behind the diplomatic life that had helped the United States win its hard-fought independence, Franklin settled back in Philadelphia. He grew rueful, waxing nostalgic for days at Passy gone by and never to be repeated.

Political factionalism already was riling the United States, and across the Atlantic deadlier trouble was brewing. When Parisians stormed the Bastille in 1789, Franklin had a year of life left. He did not live to hear of the Reign of Terror, whose victims included his friend and chessboard foe Le Veillard. As events accelerated, Franklin slowed. Increasingly, he turned away from chess and to cards and cribbage, and in a 1786 letter to the daughter of his London landlady, confessed a dread of mortality.

“But another reflection comes to relieve me, whispering: ‘You know the soul is immortal; why then should you be a niggard of a little time, when you have a whole eternity before you?’” he wrote. “So being easily convinced…I shuffle the cards again, and begin another game.”

And if, in the end, life was more a game of chance than of skill, Franklin never despaired, playing that game for all it was worth.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.