Philadelphia’s contribution to the Union war effort was as expansive and diverse as the city itself.

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Philadelphia’s size and economic output placed it second only to New York in population and prosperity among America’s cities. This enabled the city to swiftly capitalize on wartime needs.

The strength of Philadelphia’s economy lay in its diversity. Its manufacturing firms sent finished products to the rest of the nation—including the South. It was strong in textiles, iron manufacturing, shoes and boots, publishing, railroad equipment, machine tools and hardware, lumber and wood, and chemicals. Many people throughout the North believed that Philadelphia business was as closely tied to the South as to the North. Indeed, its manufacturers bought lumber, cotton and turpentine from the South while selling locomotives, Bibles and schoolbooks, carriages, wagons, clothes and shoes to Southerners. Even as late as April 1861, trainloads of consumer goods were en route to Southern customers. More than half of the students enrolled in the city’s medical schools were from south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

But the firing on Fort Sumter united the city of 565,000 people behind the Lincoln administration’s war effort. Within hours of the news, mobs of patriotic citizens roamed the streets, intimidating those who dared to declare their Southern sympathies and forcing recalcitrant newspaper editors to show the Stars and Stripes. More than 8,000 young men marched off to war within days of Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 militia to suppress the rebellion. Thousands more would don the blue in the next four years.

The war forced the city’s thriving business establishments to adapt to meet wartime needs. According to Lorin Blodget, secretary of Philadelphia’s Board of Trade, in 1860 there were 6,314 business establishments in the city. They produced an annual revenue of $141 million—second only to that of New York—and employed 98,400 workers. The more enterprising owners quickly looked for ways to land government contracts. Many subcontracted to other businesses to acquire the goods they needed. As a result, the city generally hummed with business activity throughout the war.

The hat firm of Adolph & Keen furnished 249,700 army hats, forage caps and Zouave fezzes. Hadden, Booth & Porter, a hardware business, supplied more than 200,000 canteens. Thomas Potter, listed in the city directory as an oil cloth manufacturer, must have realized a good profit from his government contracts for 375,000 haversacks, 138,500 knapsacks, 30,000 ponchos, 60,000 India rubber blankets and 50,000 tent blankets.

By 1861, Philadelphia production of railroad locomotives and wagons, and was well on its way led the nation in to becoming the largest producer of iron. The city had already developed a working relationship with iron mining operations scattered throughout Pennsylvania. Railroads brought iron ore and coal into the city, where a host of large and midsized foundries eagerly consumed the raw materials and produced gas pipes, ship boilers, iron machinery and an entire spectrum of other iron products.

Representative of these iron foundries was I.P. Morris, Towne & Company, popularly known as the Port Richmond Iron Works, founded in 1828. The firm had nine buildings crowded into its five acres along the Delaware River. A 700-foot wharf reached out into the river, with cranes to raise and lower completed boilers into waiting vessels.

During the war, this ironworks supplied boilers for several ironclad and wooden men-of-war. It also manufactured iron lighthouses as well as various large machines for a wide variety of companies and purposes.

Matthias W. Baldwin’s firm, opened in 1832, covered 20 acres by 1861 and was the nation’s largest manufacturer of locomotives. Prior to the war, many of his customers were from the South, but secession only briefly affected M.W. Baldwin & Company (later renamed the Baldwin Locomotive Works). Two related businesses assisted Baldwin’s company. The nearby firm of A. Whitney & Sons Car Wheel Manufactory could churn out 75,000 wheels for locomotives and cars per year. The company’s molding room was 460 feet long and 60 feet wide, perhaps the largest of its kind in the country. Furnaces melted the requisite iron, which was then poured into molds, each of which would take three days to cool. On the western side of the Schuylkill River was the William C. Allison Car Works. This railroad car business occupied about five acres and employed more than 300 workers. On May 2, 1863, the building complex caught fire, but Allison rebuilt and by the end of the war was back in business.

Since the locomotives used anthracite (hard) coal for fuel, the city developed a close relationship with eastern Pennsylvania’s coal industry. This centered in Schuylkill County, the Lehigh Valley and to a lesser extent the fields situated around Wilkes-Barre and Scranton. By 1860, Philadelphia imported close to half the anthracite mined in the country. Some of the coal went directly to city businesses using it for fuel. Coal was also loaded onto ships for distribution along the East Coast, while some went south around the tip of South America to San Francisco. More coal went by canal or rail to other cities in the North, where growing industrial use ensured a steady market. Colonel George H. Crosman appointed Captain Augustus Boyd to take charge of directing coal shipments from Philadelphia for the Army’s fleet of transport ships. During the 1864 fiscal year alone, the Army purchased 255,376 tons of coal for its vessels.

Philadelphia also boasted the largest wagon manufacturer in the country— Wilson, Childs & Company. Prewar sales were generally to Southern planters, who needed sturdy wagons to haul tobacco and cotton. During the war, the firm received numerous contracts to supply wagons and ambulances to the Army.

The war kept Philadelphia textile manufacturers busy. Since they were smaller than those in New England, they were able to make the shift from cotton to wool much more easily than their larger competitors because of the cost involved. One of the largest textile establishments was the Wingohocking Mills in the Frankford suburb. This mill employed 300 workers and completed 4,000 pounds of yarn each day. The Ripka Mills in Manayunk could churn out 4 million yards of cotton per year.

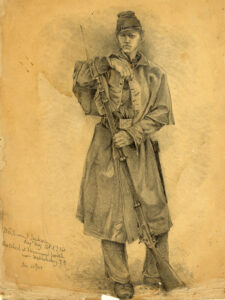

Many of the clothing businesses scattered throughout the city competed for contracts. Bloomingdale & Rhine, a wholesale clothing store, landed a single contract for 30,000 infantry greatcoats, while Joseph Newhouse, listed as a gentleman’s clothing supplier, furnished 10,500 greatcoats and 10,000 cavalry trousers. Kunkle, Hall & Company supplied 22,500 infantry greatcoats, 44,000 sack coats, 35,000 cavalry greatcoats, 57,500 infantry trousers and 45,000 infantry coats. Joseph F. Page had contracts for 26,000 cavalry greatcoats, 10,000 Veteran Reserve Corps jackets, 8,000 infantry greatcoats, 264,000 sack coats, 75,000 cavalry trousers and 325,000 shirts.

The chief Federal military installation in Philadelphia, the Schuylkill Arsenal, was a huge contractor for clothing. Established in 1799, the arsenal was the sole supplier of uniforms, clothing, shoes and camp equipment to the Regular Army. Under the supervision of the Army’s quartermaster general, the commandant of the arsenal purchased cloth by contract, had it cut into garment pieces by government-employed cutters, then issued the pieces to seamstresses across the city for final sewing and completion.

But the Schuylkill Arsenal could not hope to supply all the state volunteer units then forming. Acting on a recommendation from a military storekeeper with Mexican War experience, Secretary of War Simon Cameron approved expansion of the system. By July 1861, the Army had established a second clothing depot in New York and would eventually open a third depot in Cincinnati. As the war progressed, smaller depots appeared in other cities. But the actual purchase of cloth for uniforms was restricted to the two eastern depots in Philadelphia and New York, near the largest textile mills.

Quartermaster General C. Meigs reviewed the situation and decided that the Schuylkill Montgomery Arsenal should not be expanded but merely brought up to full working capacity, which meant that about 10,000 workers could be hired to manufacture camp equipment and cut cloth. To assist local businesses hurt by the war, Meigs ordered the implementation of a new contract system. Local businesses could bid on the contracts, thus keeping the firms afloat and workers employed. The Army would also furnish material, approved and inspected at the arsenal, to larger businesses for completion. Most contracts required the successful bidder to purchase the raw material and supply the government with finished products.

As a result, many Philadelphia merchants prospered during the war—after an initial downturn for many of the textile establishments that had to retool from cotton to the production of wool, the favored cloth for Army uniforms. Army volunteers early in the war suffered from supply shortages as Philadelphia and the rest of the country struggled to catch up with the government’s voracious need for military goods. By the end of the war, however, the Federal Army was one of the best-outfitted fighting forces in the world. This was due in large part to the success of the contracting system, and Meigs’ insistence that a large supply of essential materiel be stored in depots and warehouses for emergency use.

Other manufacturers in the city and its environs competed for government contracts for weapons and munitions. While Philadelphia was not a major weapons center, existing records show that Philadelphia-area weapons makers received $5.2 million in government contracts. Alfred Jenks & Son in Bridesburg furnished the government with 98,464 Model 1855 Springfield rifled muskets. The Phoenix Iron Works produced somewhere between 958 and 1,300 3-inch rifled cannons for the Union artillery service. Other ordnance producers included James Henry & Son (Henry carbines), Richardson & Overman (Gallagher carbines), Sharps & Hanks (Sharps carbines), Henry G. Leisenring (cavalry sabers) and Horstmann Brothers & Company (sabers and swords). Horstmann was one of the nation’s preeminent military goods suppliers when the war began. It also obtained contracts from the Cincinnati Depot to supply regimental flags to units from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, West Virginia and Minnesota. Isaac Broome received the contract to furnish 9-foot lances for the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, popularly known as “Rush’s Lancers.”

Another government installation, the Frankford Arsenal, manufactured percussion caps, paper fuses and other munitions. The arsenal staff also tested new weapons. Pennsylvania native Captain Josiah Gorgas was in command of the arsenal in 1861, but resigned on April 3. His wife was the daughter of a former governor of Alabama, so Gorgas decided to offer his services to the Confederacy, where he served as chief of ordnance. The arsenal continued its operations throughout the war under the command of Colonel Stephen Vincent Benet.

The U.S. Navy Yard, which had opened in 1800 and by 1865 employed more than 3,000 workers, was situated on the Delaware River near the center of the city. The 18-acre site featured two large ship houses and a sectional floating dry dock that enabled yard workers to attach vessels to a hydraulic engine that pulled the ships onto a railway for repairs and cleaning. The yard built and launched 10 vessels during the war. The most important was the double-turreted monitor Tonawanda; the remainder were screw sloops and gunboats.

Several other shipbuilders cashed in on the war effort and together with the Navy Yard built or overhauled more than 30 vessels. The firm of William Cramp & Sons was located on the Delaware River at the foot of Norris Street. Recognizing the growing importance of iron, Cramp had converted his firm exclusively to the production of iron vessels in the years preceding the war. Among the important vessels constructed by Cramp & Sons were the ironclad New Ironsides, the sloop Chattanooga and the gunboat Wyalusing. The firm of Neafie & Levy, known as the Penn Iron Works, was located near Cramp’s and built 120 engines for ships during the war. It also launched the U.S. Navy’s first submarine, Alligator, in April 1862.

The war also prompted creation of a system of military hospitals in Philadelphia, encompassing more than two dozen facilities with over 11,000 beds by 1865. They ranged from the small Officers’ Hospital of 50 beds to two of the largest military hospitals in the United States—Satterlee U.S. General Hospital, with 3,519 beds, and Mower U.S. General Hospital, with 3,100 beds. The hospitals employed hundreds of nurses and provided opportunities for thousands of volunteers from benevolent societies such as the Sanitary Commission and YMCA.

The city hosted a number of publishing firms, several of which received government contracts to produce military manuals. According to Francis A. Lord’s extensive list in They Fought for the Union, New York publishers (principally D. Van Nostrand) produced 105 manuals, Washington, D.C., companies printed 31 manuals and printers located in six other cities collectively printed 10 titles. Ten Philadelphia firms published 52 government manuals, with the prestigious firm of J.B. Lippincott accounting for 37.

The business boom inevitably attracted fraudulent merchants eager to supply shoddy material in return for huge profits. Some were ferreted out and prosecuted; others managed to earn a luxurious living off their gains. An 1865 inspection of the Schuylkill Arsenal revealed that four local merchants had been supplying blue kersey wool that was far below government specifications. William B. Cozens, whose firm supplied thousands of tents to the Army, was arrested in September 1864 and charged with 24 counts of fraud. He was accused of bribing inspectors to look the other way when he delivered faulty tents to the arsenal. Cozens complained that the government had no right to court-martial him, but a July 1862 law specified that anyone furnishing supplies to the government during wartime was subject to the same laws and regulations as members of the Army. During the 1865 trial, it was learned that Cozens bought his material at 1861 prices but charged the government higher prices in subsequent contracts. He also admitted that his tents were not up to government specifications, but he insisted that tents furnished by other suppliers were not either. Although the court found Cozens guilty, his supporters petitioned President Andrew Johnson, who reversed the court’s decision in 1867.

Although New York banking firms were by far the largest and most important in the country, Philadelphia provided an unexpected financial base for the war effort, thanks in large part to Jay Cooke. The son of a prominent Ohio lawyer and congressman, Cooke had moved to Philadelphia and amassed a fortune selling discounted bank notes, stocks and bonds for the prestigious E.W. Clarke & Company. When the company closed its doors after the Panic of 1857, Cooke temporarily retired and returned to Ohio.

In January 1861, Cooke returned to Philadelphia and opened the firm of Jay Cooke & Company, specializing in stocks, bills of exchange, commercial paper and government notes and bonds. Shortly after the war began, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hired Cooke to help sell state bonds worth $3 million that were used to raise and equip the Pennsylvania Reserves. Cooke did this in only two weeks.

As a result of close ties between Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase (another Ohioan) and Cooke’s younger brother, Jay Cooke was appointed as a treasury agent to assist in selling $500 million worth of Treasury Department bonds in October 1862. Nicknamed 5-20s (can be redeemed in five years, must be redeemed in 20), these bonds proved popular, all the more so because of Cooke’s aggressive marketing campaign. He advertised in newspapers, sent sample editorials to newspapers, published lists of buyers, used bankers and agents in small towns all across the North, asked ministers to espouse the sale from their pulpits and opened night offices to take money from workers who did not otherwise have the time to go to one of his regular offices. Cooke, who sold as much as $1.5 billion in bonds, later jumped on the bandwagon to help the government convince Northern bankers of the merits of a national banking system.

Even though wages of most workers increased during the war because of the shortage of skilled labor, inflation wiped out most wage gains. Prices jumped an average of 75 percent over the course of the war. Taking this into account, real wages dropped by 20 percent. The workers hit hardest by the combination of inflation and wages were the women, particularly seamstresses. Many women entered the work force to feed their families after their husbands went off to war. Private contractors paid an average of only 8 cents a shirt. In 1861 the Schuylkill Arsenal paid a seamstress 17.5 cents for each shirt; by 1864, the price was 15 cents. This uneven price scale angered many women.

By the spring of 1864, seamstresses were holding public meetings to voice their concerns. A committee traveled to Washington to see the president. Lincoln listened sympathetically and instructed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to do something about it. Stanton ordered Colonel Crosman to hire more women and raise their wages 20 percent, but this move did not address the problems with contractors.

Men also complained about wage irregularities. Knapsack strappers protested about low contractor pay in September 1861, while striking tailors attempted to coerce owners into adopting a uniform pay scale. In early 1862 Navy Yard workers, angered over a congressionally mandated pay cut, struck for a few days until the government recanted and actually increased their wages. In late 1863 arsenal shoemakers threatened to strike if they failed to receive a collective raise; their request was quickly granted to ensure uninterrupted production. There were relatively few strikes overall, however, because striking workers risked being accused of being unpatriotic.

Through initiative, diversity and adaptation, Philadelphia contributed mightily to the success of the Union war effort. The contract system enabled businesses both large and small to participate in the general prosperity of the war years, and they supplied the Federal forces with everything from ships and cannons to uniforms, blankets and tents. Thanks to the businesses and work force of the city, as well as those of other Northern cities, towns and villages, the Union Army became the best-equipped and -supplied army yet seen.

Richard A. Sauers, who writes from Williamsport, Pa., is the author of several Civil War articles and books, including the Guide to Civil War Philadelphia.

Originally published in the September 2006 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.