Political mavens were titillated to learn, via the January 6 Committee, that when President Donald Trump heard that his own attorney general, Bill Barr, had told the press there had been no widespread fraud in the 2020 election, he threw the meal he was eating at a convenient wall. “There was ketchup dripping down the wall and a shattered porcelain plate on the floor,” former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson testified. She and a valet grabbed towels to clean up the condiment.

In the annals of temperamental leaders, this is small, er, potatoes: when King Saul was angry, what he threw at David and his own son Jonathan was spears. Americans like to think, however, that our system of elected leaders is the best. The men and women we choose should therefore be better than those elevated by bloodlines, intrigues, or coups. As the country has grown in military might, however, we don’t want a loose cannon within grabbing range of the nuclear launch codes. This duality renders tales of presidential temper both scandalous and, in modern times, worrisome.

The stories begin at the beginning. George Washington had a tightly controlled temper—except when he didn’t. One outburst occurred at a cabinet meeting in 1793. Foreign policy had become a domestic political football: should the United States support the French Revolution, or politely ignore that rumpus? The specific problem for Washington and his advisers was how to handle unreasonable demands by a French diplomat, Edmond-Charles Genêt. All at the table wanted Genêt recalled, but factions split over whether the administration should lay an account of his provocations before the public. Secretary of War Henry Knox stirred the pot by producing a satirical description, in a Francophile Philadelphia paper, of Washington being led to the guillotine. Washington was not pleased. “The President,” wrote Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson in his journal that night, “was much inflamed, got into one of those passions when he cannot command himself, ran on much on the personal abuse which had been bestowed on him…that by God he had rather be in his grave than in his present situation. That he had rather be on his farm than to be made emperor of the world…He ended in this high tone.” After this eruption there was, Jefferson added, “some difficulty in resuming our discussion.”

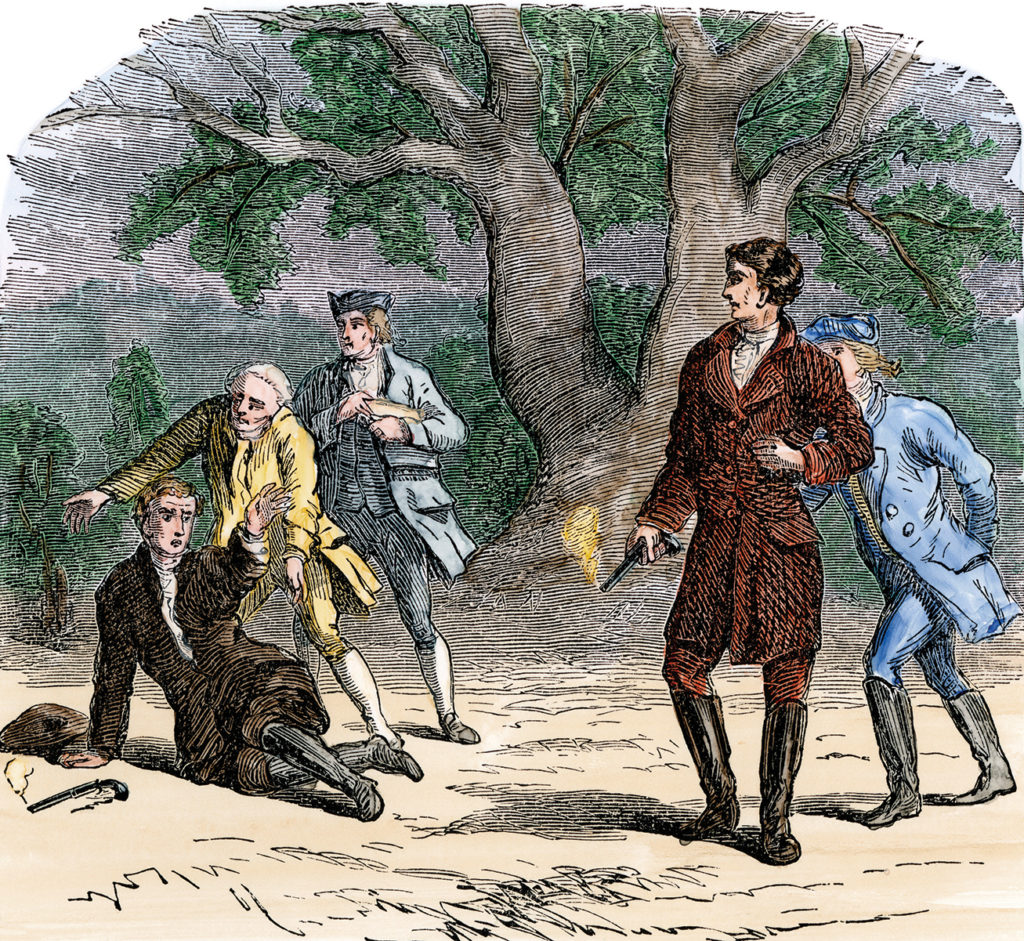

Andrew Jackson was a fighter, on and off the field. Before he was elected to the White House, he had been shot in a duel in which he killed his man, and was also wounded in an armed brawl in a hotel with his own officers. In 1835, during Jackson’s second term, a would-be assassin fired two pistols at him as he was leaving a congressman’s funeral at the Capitol. Both weapons misfired, and Jackson clubbed his attacker with a cane—a reasonable response, considering the circumstances. But the president unreasonably told anyone who would listen that the gunman, Richard Lawrence, had been put up to the assault by George Poindexter, a Mississippi senator with whom Jackson was then feuding. Lawrence was in fact a lunatic housepainter who imagined himself to be the legitimate king of England. He had once painted Poindexter’s house, but there was no evidence that the two were in cahoots; a jury found Lawrence insane after only five minutes’ deliberation. Harriet Martineau, an English sociologist who happened to be in Washington at the time, found Jackson’s tirades against Poindexter embarrassing.

“The President’s misconduct on the occasion was the most virulent and protracted,” Martineau wrote. “It was painful to hear a Chief Ruler trying to persuade a foreigner that any of his constituents hated him to the death, and I took the liberty of changing the subject as soon as I could.”

Andrew Johnson became Abraham Lincoln’s running mate, and ultimately his successor, based on Johnson’s loyalty to the Union despite being a senator from Tennessee. But there was no charity for all in Johnson. In February 1861 he had a conversation with Charles Francis Adams, Jr., 25-year-old sprig of the Massachusetts presidential clan, in which Johnson railed at secessionist colleagues. David Yulee of Florida was a “miserable little cuss,” a “contemptible little Jew,” and a “despicable little beggar.” Judah Benjamin of Louisiana was “another Jew….He looks on a country and a government as he would on a suit of old clothes. He sold out the old one; and he would sell out the new if he could in so doing make two or three millions.” Louis Wigfall of Texas—a gentile, for a change—Johnson called “a damned blackguard” and a bankrupt, explaining that “the strongest secessionists never owned the hair of a n——.” What was remarkable about this splenetic display was not Johnson’s opinions of these men, who were after all working to destroy the country, but that he should express them so vividly to a kid he barely knew.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Dwight Eisenhower’s mile-wide smile, his nickname rhyming with like, and his tangled syntax conveyed an air of innocent geniality. But on the eve of Ike’s first run for the presidency journalist Murray Kempton provoked his wrath. Senator William Jenner, Indiana Republican, had called Secretary of Defense George Marshall “a living lie,” holding Marshall responsible for losing China to communism, entangling us in NATO, and everything else about the world that the isolationist Jenner disliked. Kempton asked Eisenhower, whose mentor in the Army had been Marshall, what he thought of the charges. “He leaped to his feet and contrived the purpling of his face,” Kempton wrote. “How dare anyone say that about the greatest man who walks in America?…He would die for George Marshall. He could barely stand to be in the room with anyone who would utter such a profanation.” Kempton felt like an enlisted man being reamed as “an example to the rest of the troops.”

It is unlikely that anyone ambitious enough and compelling enough to rise to the top does so without some degree of temper in his or her makeup. Temper can be the shadow of forcefulness. The question for those who possess a temper is, can they control it, or does it control them? After Washington lost his cool in front of cabinet members, he and they returned to the question of whether to publicize Genêt’s misbehavior, and he decided: not yet. Washington’s critics could imagine chopping off his head, but he would not be provoked by a journalistic screed into losing it. Murray Kempton realized even as Eisenhower was bawling him out that the would-be Republican nominee had not criticized Senator Jenner. Ike would defend his idol, but not condemn his idol’s slanderer so long as he needed the slanderer’s support.

Andrew Jackson’s admirers then and since claim that Old Hickory used his wrath as Ike did, for momentary effect. “I never saw him in a passion,” testified Amos Kendall, one of Jackson’s senior cronies. Kendall must have been out of town in 1835. Andrew Johnson has almost no admirers to stick up for him, and why should he? His impulses, violently anti-rebel then equally violently anti-Black, crippled Reconstruction out of the gate.

Once in a while a leader emerges whose veins run with the milk of human kindness. Secular saint Lincoln is one example; another is Ulysses S. Grant who, though he killed thousands in battle, was in peacetime benevolence itself. But most leaders, like most of us, are human, all too human. The good ones don’t leave ketchup on the walls. But it is always wise to clear the table after every course.