Major General Benedict Arnold’s 1780 plot to surrender the American fortifications and garrison at West Point to the British, one of the Revolution’s most dramatic episodes, nearly succeeded. Arnold’s treasonous undertaking failed thanks to a remarkable convergence of events—events that many, including General George Washington, could explain only as divine intervention. “In no instance since the commencement of the war has the interposition of Providence appeared more conspicuous than in the rescue of the post and garrison of West Point from Arnold’s villainous perfidy,” he said later. Scrutiny reveals the sequence’s more mundane logic, whose conflicted outcome severely tested Washington.

British commanding General Sir Henry Clinton first negotiated terms with Arnold through ciphers and intermediaries, then insisted on a face-to-face meeting between a trusted subordinate and the turncoat. Clinton wanted to ascertain that Arnold’s proposition was not a ruse to set up Crown forces for an ambush. The Briton he assigned to vet the supposed turncoat Arnold and his proposal was Major John André, barely 30 years old, a dashing adjutant general Sir Henry held in much the same esteem as Washington held the Marquis de Lafayette.

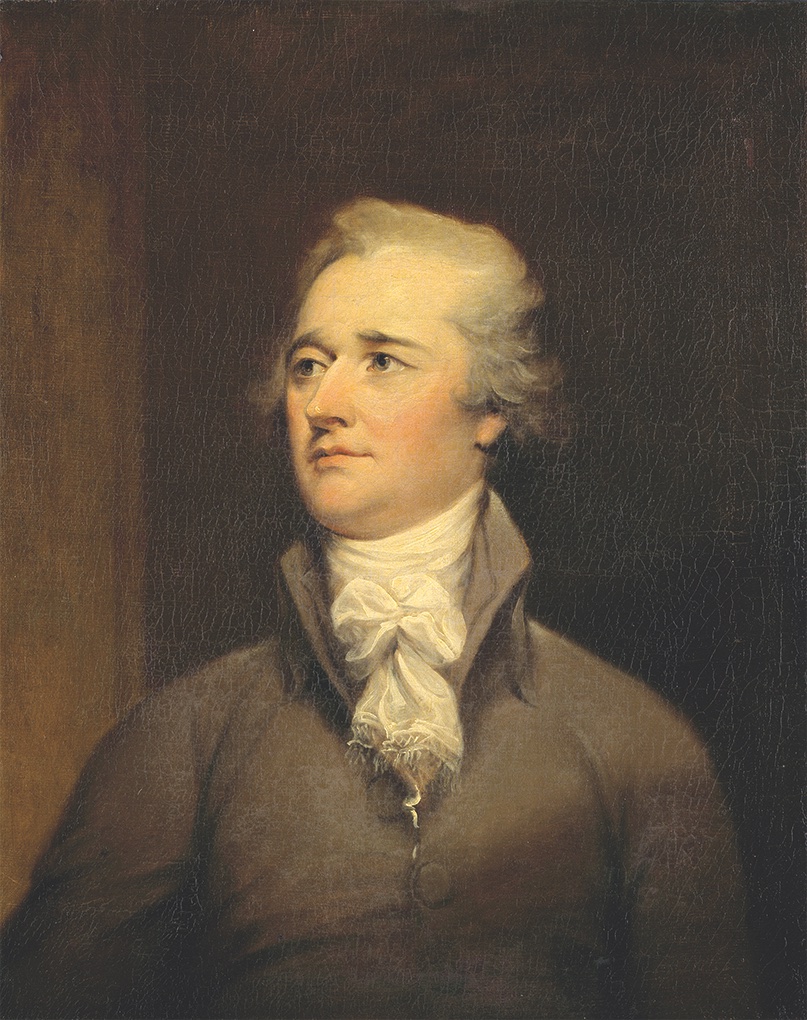

A seasoned intelligence officer, André was accomplished, well educated, and by many accounts charismatic. He spoke fluent German and French—his parents were wealthy Huguenots, his mother a Parisienne—and was schooled in painting, music, and verse. He wrote poetry. Over the years a composite portrait has evolved of a charming, gentlemanly warrior.

André

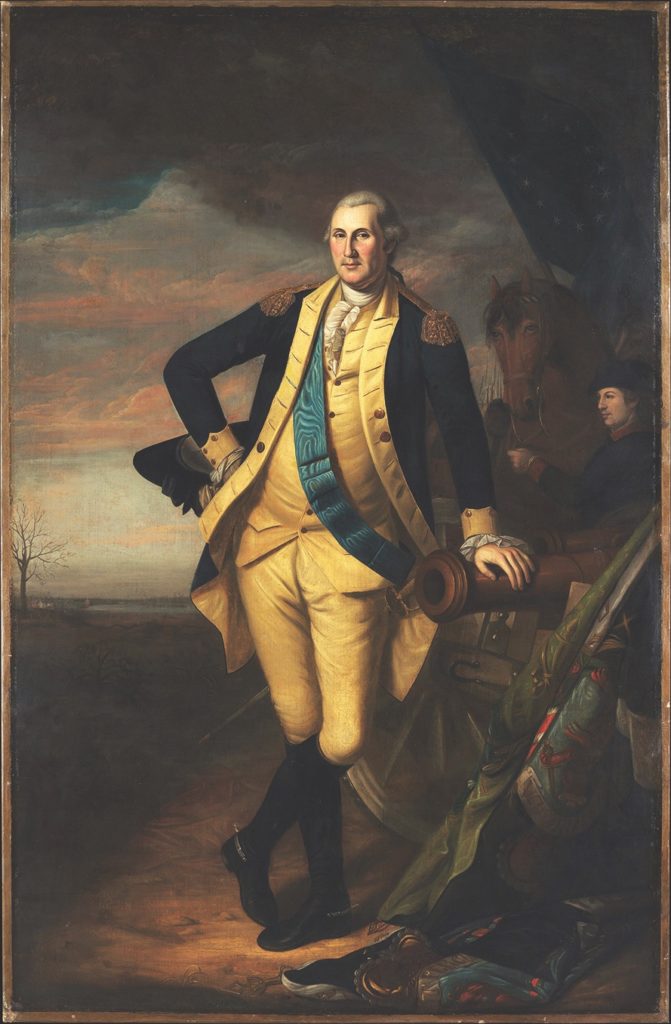

Arnold

Clinton

(New York Public Library; Niday Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo; The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Historian Nathaniel Philbrick is not buying it. Philbrick sees in André a bloodthirsty and ambitious careerist who “developed a chameleon-like talent for ingratiating himself with whoever might be useful to him.” There was “an edgier, even ruthless side to the British captain,” Philbrick maintains, noting that André was present at the Paoli Massacre in 1777 when British troops attacked Americans led by General Anthony Wayne. The historian quotes André as writing afterward that the British troops put “to the bayonet all they came up with and, overtaking the main herd of the fugitives, stabbed great numbers [of them]. He noted they were “stabbed…till it was thought prudent to…desist.”

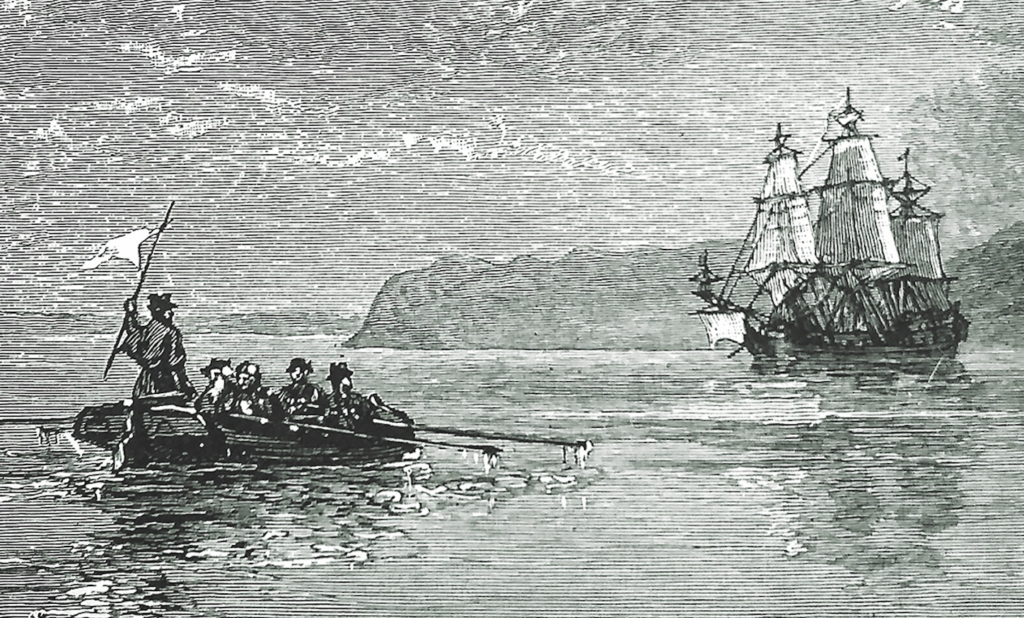

There is no doubting André’s ambition. He had been involved in negotiations with Arnold from the beginning and wanted to guide them to a successful conclusion. The capture of West Point and its 4,000-man garrison could well be the turning point of the war—and of his career. As Hessian Captain Johann Ewald said, “If this affair had had a successful result, it would have put an end to the war, preserved the thirteen great and beautiful provinces for the Crown of England, and made Major André immortal.” André won his commander’s grudging approval to travel from New York City to the British warship Vulture, anchored in the Hudson about 14 miles downstream from Arnold’s headquarters. Clinton made clear that André was not to be out of his uniform or to go behind enemy lines. André made the trip on a small boat, arriving aboard Vulture on September 20.

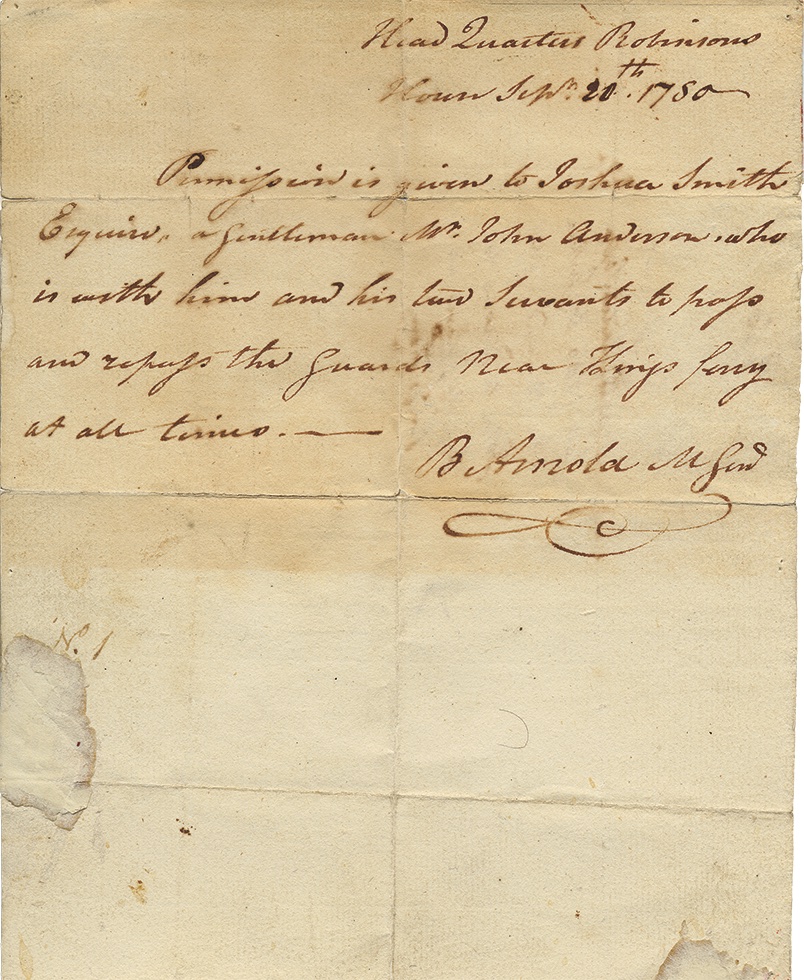

After several false starts, on the evening of September 21, 1780, Arnold sent associate Joshua Hett Smith to Vulture. Smith brought a pass signed by General Arnold assuring the safety of one “John Anderson.” André was to pose as “Anderson,” ostensibly a merchant conducting business involving the residence at West Point of loyalist William Robinson, whose home was serving as Arnold’s headquarters. André, his regimentals scarcely covered by a large blue greatcoat, accompanied Smith as two oarsmen ferried them to the west bank of the Hudson. Arnold was waiting on shore with horses to escort the men several miles to Belmont, Smith’s house, for the final negotiations. It was already the wee hours of Thursday, September 22. Arnold’s and André’s conversation while Smith was in another room is lost to history. Besides locking in Arnold’s price, André obtained from the American details on West Point’s defenses. For whatever reason, the negotiations were lengthy, and daybreak was near when they finished.

The British officer displayed “an edgier, even ruthless side,” with a “chameleon-like” personality.

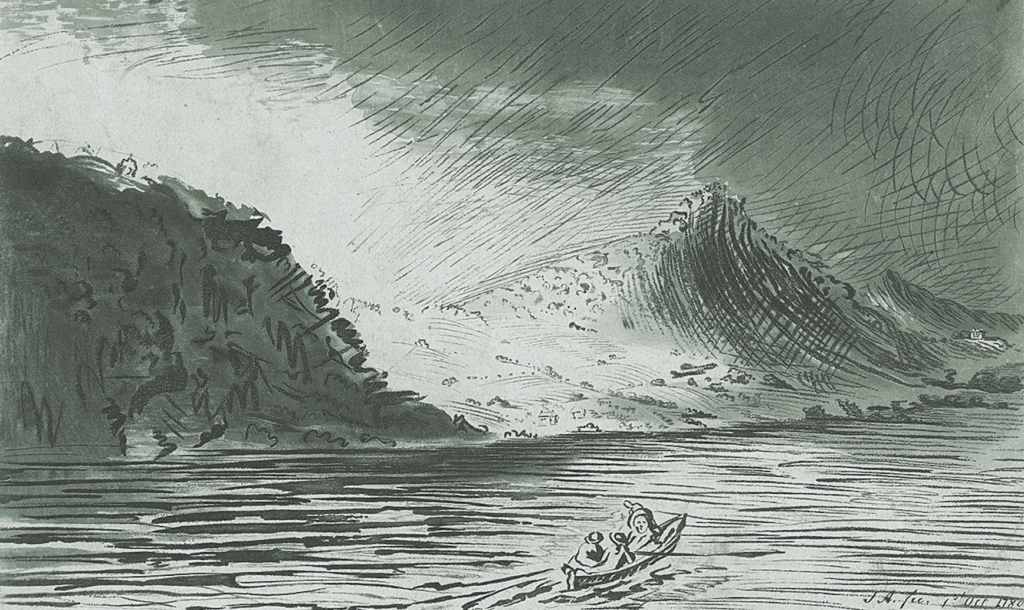

At this point things went awry. Vulture was no longer within rowing range, having been driven several miles downstream by patriot batteries on Teller Point that unaccountably opened fire on the ship. The impetus might have been the actions of Jack Peterson, a Black patriot soldier, who with a companion fired on a Vulture bumboat, killing at least one oarsman

Denied a watery route to safety, André had to make for New York City, roughly fifty miles south, by land. This meant traveling behind enemy lines while carrying incriminating documents. Arnold insisted that André don one of Smith’s coats to cover his uniform and wrote passes for use by André and Smith who, with his body servant, was to guide André back to New York City via British-held White Plains. The pass André carried read, “Permit Mr. John Anderson to pass the guard to the White Plains or below, if he chooses, he being on public business for me.”

Not until very late in the afternoon of September 22 did André and his companions begin their trek. They crossed the Hudson River at King’s Ferry and made their way east and south toward New York City, passing several patriot positions and spending a restless night sharing a single bed. The following morning, as the three were approaching Piney Bridge, Smith dropped a bombshell. He declared he was turning back, likely for fear of the territory ahead. Smith went with the Briton as far as Piney Bridge.

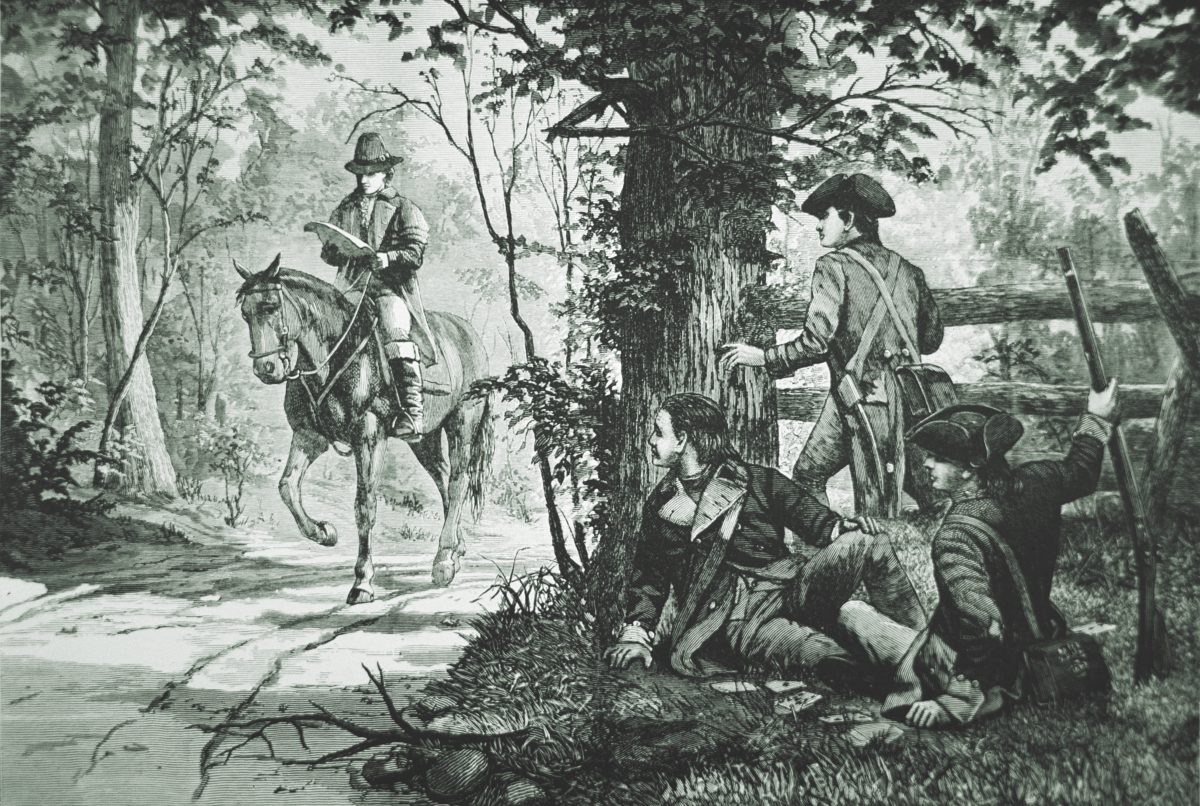

André continued alone for approximately 30 miles. Near Tarrytown on Friday, September 23, three armed civilian roughnecks accosted him. One wore a green shirt of the style favored by Hessians fighting for the Crown. Guessing he had stumbled upon compatriots, André admitted to being with the British.

He could not have made a bigger mistake. Later hailed as heroes by some and painted as brigands by others, John Paulding, Isaac Van Wort, and David Williams were perhaps both. The trio apparently had thought at first to rob their quarry, but when they discovered Arnold’s maps in his boot, they refused the Englishman’s offer of a bribe and took him and his bogus pass to the American authorities. Apprised of possible monkeyshines, the slow-thinking officer they consulted, a Lieutenant Colonel Jameson, sent a message to Arnold that someone was using passes in his name, enough of an alert to give Arnold time to flee to Vulture.

André was conveyed under heavy guard to Washington’s headquarters, then at the residence of a family named Robinson. There is no evidence that Washington interviewed the prisoner. Next André was taken to Tappan, a town where the main American army was camped. The patriots confined André in Mabie’s Tavern, at the foot of a steep hill in Tappan, for less than a week before a 14-member military court presided over by Major General Nathaniel Greene tried him.

As a prisoner André completely captivated Americans with whom he had contact. His chief guard, Benjamin Tallmadge, declared, “I can remember no instance where my affections were so fully absorbed in any man.” Alexander Hamilton waxed poetic in describing André. “To an excellent understanding well improved by education and travel, he united a peculiar elegance of mind and manners, and the advantage of a pleasing person,” Hamilton wrote. “His knowledge appeared without ostentation, and embellished by a diffidence, that rarely accompanies so many talents and accomplishments. His sentiments were elevated and inspired esteem. They had a softness that conciliated affection. His elocution was handsome; his address easy and polite.”

But charm was no guarantee against the evidence. The tribunal voted unanimously to convict the prisoner of espionage. André was slow to realize that Arnold’s treachery was going to cost him his life. When he did grasp his situation, he had only one request—that he be shot like a soldier, not hanged, the disgraceful end reserved for spies, traitors, and their ilk. “Buoy’d above the Terror of Death by the Consciousness of a Life devoted to honorable pursuits and Stained with no Action that can give me Remorse,” André wrote to Washington. “I trust the request I make to your Excellency at this Serious period and which is to Soften my last moments will not be rejected.”

His prisoner’s request presented Washington with a dilemma. The general’s animus was personal and aimed at Arnold, not at André. Washington had trusted and supported Arnold, rewarding him with the command at West Point, only to have the man respond with “treason of the darkest dye,” a betrayal that cut the general to the quick. Washington prided himself on his ability to judge men, and it mortified him to have been so wrong about Arnold. He desperately wanted Arnold to pay mortally for his treachery.

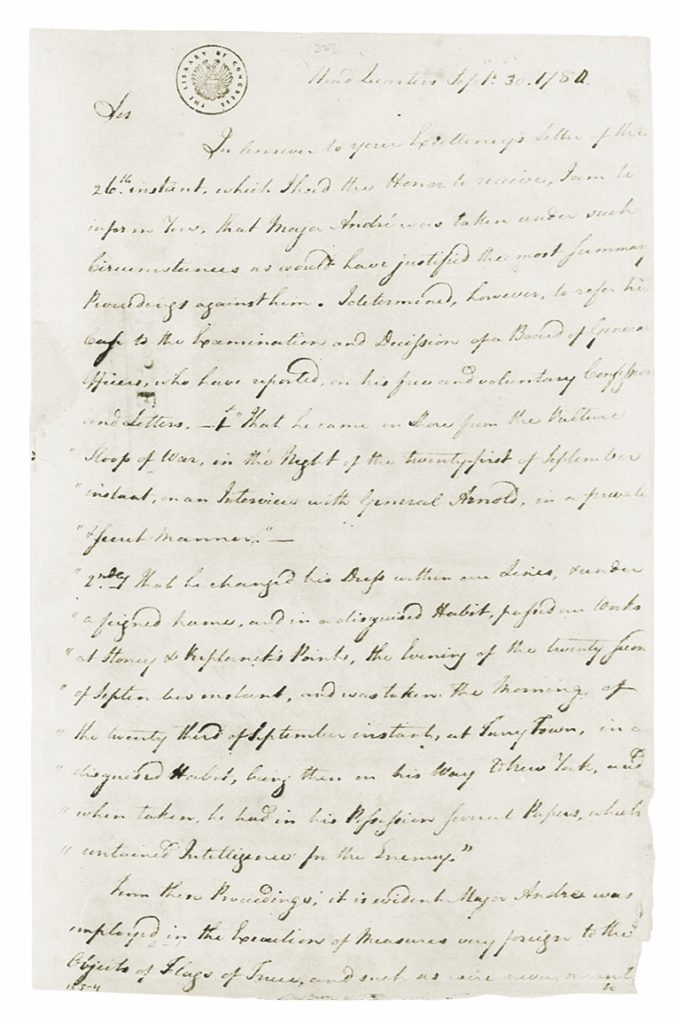

Through unofficial channels Washington made clear to Clinton that to save his beloved André the British commander had to hand over Arnold. Not wishing to discourage other prospective American turncoats, Clinton refused. He warned Washington against putting André to death. “I have not any the least doubt but your Excellency will be cautious of putting to Death an Officer of the British Army under my command,” Clinton wrote. “And I am perfectly convinced of the real humanity which governs your conduct on all occasions and it will assuredly lead you, Sir, to not suffer too sudden an operation of so violent a measure.”

The facts were compelling. André had not come ashore under a flag of truce, a fact he acknowledged. He was engaged in espionage, and he had been captured behind enemy lines out of his military uniform with incriminating documents, making him a spy and not a prisoner of war. The accepted punishment for espionage was the ignominy of death by hanging. Washington concluded he had no other option.

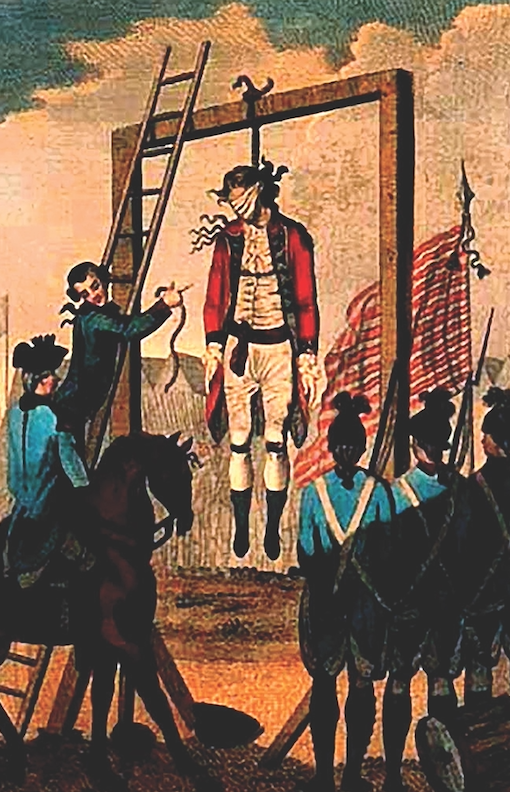

By all accounts, André’s execution was an emotionally charged event that left an indelible impact on those present.

Hamilton

Washington

(Yale University Art Gallery; Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The sentence was carried out before thousands of Continental Army troops at Tappan on October 2, a day later than planned due to a last-ditch British proposal which proved unacceptable. Military surgeon Dr. James Thacher recalled that upon seeing the gallows on the hill overlooking Mabie’s Tavern from which he was to hang, André recoiled. “I am reconciled to my fate,” he said. “But not to the mode.” André knew hanging to be a gruesome end, often involving loss of bowel control, an affront to his soldierly sensibilities and dignity.

Quickly collecting himself, the doomed man added, “It will be but a momentary pang,” according to eyewitness Thacher. “Springing upon the cart [André] performed the last offices to himself with a composure that excited the admiration and melted the hearts of the beholders,” he wrote. “Upon being told the final moment was at hand, and asked if he had anything to say, he answered: ‘nothing, but to request you will witness to the world, that I die like a brave man.’”

“When I saw him swinging under the gibbet, it seemed for a time as if I could not support it,” Tallmadge recalled. “All of the spectators seemed to be overwhelmed by the affecting spectacle, and many were suffused by tears. Perhaps no person ever suffered the ignominious death, that was more regretted by officers and soldiers of every rank in our army.”

In Lafayette’s words, André “behaved with so much frankness, courage and delicacy” that one could not help but lament his fate.

After the trial, Washington wrote to British counterpart Clinton (right) seeking to swap his condemned prisoner for the turncoat Arnold but Clinton was unwilling to make a deal.

(Library of Congress; Hulton Archives/Getty Images)

André’s execution outraged the British. Clinton never overcame his anger at Washington for the hanging. “The horrid deed is done W has committed premeditated murder, he must Answer for the dreadful Consequences,” Clinton wrote. In a memoir, Clinton asserted that Washington “burnt with a desire of wreaking his vengeance . . . And consequently, regardless of the acknowledged worth and abilities of the amiable young man who had thus fallen into his hands, and in opposition to every principle of policy and call of humanity, he without remorse put him to a most ignominious death.”

André’s close friend, Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe, excoriated Washington. “It is my most ardent hope, that on the close of some decisive victory, it will be the regiment’s fortune to secure the murderers of Major André, for the vengeance due to an insulted nation, and an insulted army,” Simcoe wrote. “It has fixed an indelible stain on General Washington’s character—a stain which no time can efface. . . His name will be transmitted to posterity with this hateful circumstance—that he was the unrelenting MURDERER of Major André.”

The hanging outraged the british. For the rest of his days Clinton burned with anger over Washington’s refusal to spare Andre’s life.

Hamilton was among patriots critical of Washington’s decision to hang André. “I must inform you that I urged a compliance with André‘s request to be shot, and I do not think it would have had an ill effect; but some people are only sensible to motives of policy, and sometimes from a narrow disposition mistake it,” Hamilton wrote on October 2 in a letter to his fiancée, Elizabeth Schuyler. “When André’s tale comes to be told, and present resentment is over, the refusing him the privilege of choosing [the] manner of death will be branded with too much obduracy.”

Washington did not lightly send André up that hill in Tappan. Always a stickler for protocol, he felt he had no choice. “It was the duty of General Washington to see that sentiment did not prompt leniency toward a man engaged in the most dangerous conspiracy the war had hatched,” a prominent historian wrote.

Washington held André in high personal regard, viewing him more as a victim of misfortune than as a guilty party. He wrote to but never interviewed André. Not wanting his prisoner to dwell any longer than need be on the grotesquerie of his demise, Washington pointedly did not answer a letter from the accused requesting to be shot.

Following the hanging, the General wrote, “André has met his fate, and with that fortitude which was to be expected from an accomplished man and gallant officer.” Nephew Bushrod Washington later wrote, “On perhaps no other occasion in his life did Washington obey with more reluctance the stern mandates of duty and policy.”

Washington was inordinately sensitive to criticism, and one riposte to his handling of the André matter struck him hard. Among the most widely circulated commentaries on the incident was “Monody on Major André,” a poem by celebrated British poetess Anna Seward, a friend of fellow poet André. The first stanza reads, “Oh WASHINGTON! I thought thee great and good,/ Nor knew thy Nero—thirst of guiltless blood!/ Severe to use the pow’r that Fortune gave,/ Thou cool determin’d Murderer of the Brave!/.”

In an 1802 recollection, Anna Seward made a surprising claim that has the ring of truth. In a letter she explained that after the Revolution Washington sent an aide to see her in Britain. The man presented his hostess with copies of letters Washington had written to André during his brief captivity and André’s replies in the dead man’s own hand.

“Concern, esteem, and pity, were avowed in those of the General, and warm entreaties that he would urge General Clinton to resign Arnold in exchange for himself, as the only means to avert that sacrifice which the laws of war demanded,” Seward continued. “Washington did me the honor to charge his aide-de-camp to assure me, that no circumstance of his life had given him so much pain as the necessary sacrifice of André’s life, and that next to that deplored event, the censure passed upon himself in a poem which he admired, and for which he loved the author; also to express his hope, that, whenever I reprinted the Monody, a note might be added, which should tend to acquit him of that imputed inexorable and cruel severity which had doomed to ignominious death a gallant and amiable prisoner of war.”

History came to judge André and Washington as honorable. André is memorialized at Westminster Abbey, Washington, as the father of his country. Each did what he believed to be his duty. There is honor in that.