The B-52 flight back to Guam was uneventful until they began their final approach, when the co-pilot shouted, “The flaps are splitting!”

It had been nearly 12 hours since Captain Bob Amos had taken off from Andersen Air Force Base in Guam on a B-52 bombing mission to strike targets near Saigon. As he piloted his Stratofortress into its approach for landing back at Andersen, slowing to 220 knots and lowering the flaps, his co-pilot, Captain Lee Meyers, shouted out, “The flaps are splitting!”

Amos ordered Meyers to raise the flaps as he corrected a rolling moment to the left, and then declared an emergency as he pulled out of the bomber stream and climbed to gain altitude. What had been an uneventful flight was now getting hairy, all the more so because of the man who was seated behind Amos in the instructor pilot seat. Visions of screaming newspaper headlines hitting doorsteps across America raced through his head: “Jimmy Stewart Killed in Bomber Accident with Bob Amos Piloting!”

Surprise Passenger

Recommended for you

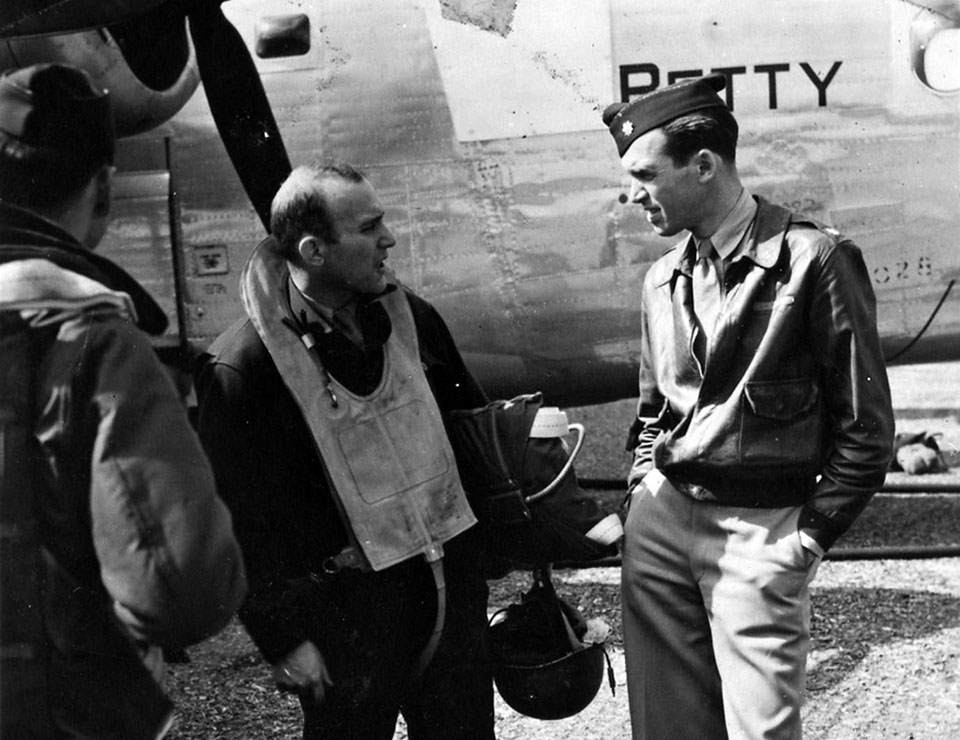

Early the day before, February 20, 1966, Captain Amos was thumbing through the flight schedule in preparation for the mission he and his crew would fly the next day, and he was surprised to see that there was a “Brigadier General Stewart” listed as an extra pilot to fly with them. Figuring this Stewart was probably from Strategic Air Command (SAC) headquarters coming along as an observer, Amos nonchalantly asked his squadron commander, Lt. Col. Collins Mitchell, who the visitor was.

“You know, Bob, it’s Brig. Gen. Jimmy Stewart, the actor! He’s over here on an active duty reserve tour, and we wanted him to fly with a young crew that would be reminiscent of the World War II crews he commanded while flying B-24 Liberators out of England, and to see how we were supporting the troops in Vietnam.”

Amos could hardly wait to break the news to his crew, a lead crew that had already flown 20 combat missions over South Vietnam. Strategic Air Command had been reluctant to contribute the B-52 to the war, but General William Westmoreland asked for the B-52 to hit known Viet Cong strongholds in the south. Amos’ crew was of the 736th Bomb Squadron, from the 454th Bomb Wing, under the command of the 3rd Air Division. Originating out of Andersen AFB, Guam, there were no short flights—missions generally took at least five hours just to reach their targets.

Long Mission

General Stewart and the 454th Bomb Wing commander, Colonel William Cumiskey, attended the special mission briefing late that afternoon. It would be a long, nonstop mission requiring aerial tanker support. Captain Amos’ crew had prepared a series of extra maps and charts depicting the operation over South Vietnam, and Amos outlined the mission, air refueling and recovery procedures back at Guam. The sortie would be against a suspected VC stronghold and bivouac area northwest of Saigon, where the potential threat was from Cambodian-based MiG-17s.

Amos’ bomber would be designated Green-2 in a 30-ship bomber stream mission named New Car-1. Before leaving, Amos had his tail gunner, Tech. Sgt. Demp Johnson, go to the commissary and buy fresh eggs, bacon, bread and cheese so they could have scrambled eggs and bacon along with grilled cheese sandwiches on the long five-hour flight back to Guam. With the B-52’s large upper cockpit and power outlets, the crew had gotten accustomed to using an electric frying pan to prepare hot meals to supplement the standard in-flight lunches provided.

Jimmy Stewart had developed a love of aviation long before he became a famous actor. He took his first airplane ride in a Curtiss biplane while he was in high school—15 minutes for $15 that he had saved while working around the family’s J.M. Stewart Hardware Store in Pennsylvania. When Charles Lindbergh made his historic ocean crossing from New York to Paris in 1927, Stewart created a window display of it for the store, complete with a model of the Spirit of St. Louis that he built. The 19-year-old Stewart would race across the street to the newspaper office to get updates of Lindbergh’s progress off the teletype, then return to the store window to move the model plane closer to the Eiffel Tower he had fashioned.

After graduating from Princeton University, Stewart passed a screen test in New York in 1935, and moved to Hollywood under contract to MGM. His success allowed him to fulfill his lifelong dream to fly, and he received his private pilot’s license that same year, followed by his Commercial Pilot Certificate in 1938. He owned a Stinson 105 two seater and often flew cross-country to visit his parents in Pennsylvania. The leading role in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington made Stewart a megastar in 1939, the same year that Adolf Hitler’s army stormed into Poland.

Volunteering for the war effort

Stewart, whose father and grandfather had both served during wartime, wanted to fight for his country—but MGM did everything it could to dissuade him from enlisting. Then he was drafted in 1940, and after he was turned down because his weight did not meet the required minimum, he decided to volunteer. In February 1941, the 32-year-old Stewart finally managed to pass his physical, and in early March, seven days after receiving the Academy Award for Best Actor in The Philadelphia Story, he received his orders to report for duty as a buck private.

Assigned to the Army Air Forces, he was sent to Moffett Field in San Francisco and quickly met the qualifications to start flight training. He won his wings in early 1942 and received a commission as a second lieutenant. His ultimate goal was to fly combat overseas, but he got bogged down Stateside as a flight instructor in Boeing B-17 bombers. The main obstacle to getting into combat was not with Stewart’s piloting ability but the fact that commanding officers did not want to risk losing a high-profile movie star in combat.

Finally in summer 1943, through a friend in higher places, Stewart managed to wrangle a transfer into a Consolidated B-24 bomber squadron that was in its final stages of training for combat in the European Theater as part of the Eighth Air Force’s 445th Bomb Group. He arrived in England in November 1943, and two weeks later Captain Stewart was flying his first bombing mission against Nazi Germany.

As squadron commander of the Brunswick mission over Germany in February 1944, Stewart earned the Distinguished Flying Cross, for holding the formation together during Luftwaffe fighter attacks and heavy antiaircraft fire, and for directing a bombing run in which the bombs were accurately released over the target. His abilities as a pilot and his leadership skills moved him up the ladder quickly. In March, after flying 12 missions with the 445th, Stewart was reassigned to the 453rd Bomb Group and promoted to operations officer.

He directed the bombing operations of approximately 48 Liberators, as well as still being permitted to make occasional combat flights as a pilot. He flew eight more such missions, including one over the heart of Berlin, in which he lost several of his men. Badly shaken, but not physically injured, Stewart recuperated in the hospital for several weeks and, reluctantly, agreed to end his combat flying. For the rest of the war, he conducted combat briefings at Hethel Airfield in England while serving as wing operations officer and chief of staff for the 2nd Combat Bomb Wing. By war’s end, Stewart had reached the rank of colonel and had been awarded a number of decorations, including two Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals.

Back to Hollywood

Stewart received an honorable discharge that summer and returned to his Hollywood career, maintaining his military career as well, as a colonel in the Air Force Reserve. Even though his return to movie making took up most of his time, Stewart conscientiously attended his Reserve drills. In 1959, President Dwight Eisenhower promoted the 51-year-old Colonel Stewart to the rank of brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve, a controversial appointment in which his celebrity status had actually worked against him. At the first mention of Stewart’s one-star promotion two years earlier, a political firestorm had erupted, but the Air Force stood behind Stewart and reassigned him to a more prestigious post, easing his eventual confirmation by the U.S. Senate. Throughout his years in the Reserves, Stewart maintained familiarity as a SAC bomber pilot in the B-36, then the B-47, and finally the B-52.

Now, 22 years and one day since he had earned his first Distinguished Flying Cross for his Liberator mission over Germany in 1944, General Stewart was going on another combat mission—to Vietnam—seated in a B-52 behind Captains Amos and Meyers. The pilots ran through the checklists, fired up the engines and departed Andersen field for the five-plus hours flying time to their target. When it came time to refuel, some three hours later, Amos contacted the tanker’s boom operator while in the precontact position behind the KC-135.

Amos had Stewart repeat the command: “Green-2 stabilized in the precontact position. Ready for contact.” There was an unusually long pause before the tanker boom operator responded, as though he might have been trying to remember where he had heard that voice before. “Cleared for contact,” he finally said. At plug in, Stewart replied, “Contact.” After refueling, Amos let the tanker know who the extra pilot was. The boom operator replied: “Thank you sir, it was our pleasure to serve you. Today we are giving double stamps.” Stewart had a good laugh.

the approach

As they approached the coast of South Vietnam and were running their checklists, Stewart asked if they were at the Pre-Initial Point on the map. He then moved to the edge of his seat so he could view the bomb impacts of the aircraft ahead of them. Green-2 was at 33,500 feet, 500 feet above and two miles behind the lead bomber, Green-1. Green-3 was 500 feet above and two miles behind Green-2. The radar navigator, Captain Irby Terrell, found and tracked the bombing offset, and the Time to Go (TG) indicator started the countdown. At TG zero, they started the release of 51 M-117, 750-pound bombs.

Each of the 30 B-52s had an individual bombing aim point so as to completely saturate the rectangular target box where the VC were reportedly located. The bombs were fused to penetrate the many caves and fortifications that were in the target area. When the strike camera film was processed back at Andersen, the crew learned that their bombs fell well within the desired Circular Error of Probability (CEP) that was required to hit the desired target.

When safely outbound off the coast of South Vietnam, Captain Kenny Rahn plugged in the electric frying pan and prepared the planned meal for the crew. “You all really know how to top off a successful bomb run,” Stewart said as he enjoyed his scrambled eggs, bacon and grilled cheese sandwich.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Emergency Situation

The flight back was uneventful until they began their approach to Guam. Thinking his flaps were damaged, Amos knew that a “flaps-up” landing in the B-52 was possible but he had only practiced it in training down to an altitude of 500 feet above the runway and no actual touchdowns were ever made. The B-52’s attitude during the approach to landing is dramatically different in a flaps-up approach and landing: The normal nose-down attitude becomes a nose-up attitude and requires a different technique in flaring and controlling the sink rate of the aircraft for touchdown with its bicycle-type landing gear.

Now in an emergency situation, Maj. Gen. William J. Crumm, 3rd Air Division commander, came on the radio and asked if they could verify that the flaps had actually split. Amos radioed back: “There was a mild rolling moment to the left, but it wasn’t severe and could have been from the B-52 in front of us….By the time the tail gunner got a view of the flaps, both of them were back in the up position.” Crumm then asked Amos’ thoughts about trying the flap extension again, after moving General Stewart down to the instructor navigator position in case of a possible bailout should the aircraft become uncontrollable. Amos gave the thumbs up to Meyers, who concurred.

“I’m going to extend the flaps again,” Amos told Crumm. “With a 20-degree flap differential, we should have experienced a more severe rolling moment.” General Crumm agreed, and they proceeded to the planned bailout area north of the base where ground- and water-based survival support was on alert.

As Amos flew into the abort area north of Andersen, the crew started to calculate the flaps-up landing data: airspeed plus-35 knots; landing roll—longer; if drag chute failure—50 percent longer. He then escorted Stewart to the instructor navigator position on the plane’s lower deck. “If I lose control of the aircraft,” Amos said, “I will call out over the intercom ‘bailout’ three times and activate the bailout light. The navigator will be the first to go, creating a large hole by his downward ejection seat.” Amos reassured Stewart that he would do everything he could to regain control of the bomber and would be the last to leave the aircraft.

“Do you understand, General Stewart?” Amos asked.

“Yes, Captain Amos, I understand,” Stewart very calmly answered in his familiar granular voice.

Amos verified that everyone was prepared for a possible bailout, and they began their approach in the abort area. “Lower the flaps,” Amos ordered to Meyers. The gauge again indicated a splitting condition, but both left and right flaps were extending normally without any rolling moment! Amos informed the command post: “It was a bad flap gauge, not a flap malfunction…our previous rolling moment was probably turbulence from the B-52 ahead of us in the bomber stream.” A relieved General Crumm told them “to bring her in.”

Precious Cargo

In the meantime, everyone knew that Jimmy Stewart was aboard the Green-2, and the airfield was abuzz with emergency equipment and several staff VIPs and aircrews awaiting the flaps-up landing. Later, Amos would recall: “We popped over the horizon heading westerly to the Andersen runway with flaps down. There was to be no flaps-up landing that day!”

The official time in the air for the mission was 12 hours and 50 minutes. After taxiing in, the plane was greeted by a number of VIPs, and Stewart suggested a photo of himself and the flight crew to commemorate the mission and successful landing. While the crew proceeded to the mission debriefing area, the general was escorted to the famous “Beer Barrel” area to lift a few with the flight and maintenance crews, swapping World War II and Arc Light stories. Amos’ crew joined the Beer Barrel celebration later.

The following morning as Amos and his crew were planning for the next mission, an announcement came over the loudspeaker that the wing commander wanted Captain Amos to meet him in front of the building immediately. As he rushed outside, he found General Stewart seated in the CO’s car. Stewart told Amos, “I wanted to thank you for a successful combat mission and your professionalism during the in-flight emergency.” Stewart then presented the captain with a set of personalized autographed photos, taken after they landed, for each member of the crew, and he wished all of them good luck. For the general, it was his last combat mission.

Storied Career

Captain Amos went on to fly a total of 34 combat missions in the B-52F over South Vietnam and later 126 missions in the F-105D, including 100 missions over North Vietnam. He retired as a colonel from the U.S. Air Force in 1984, after 26-plus years with a total of 5,094 flying hours. In his last flying assignment, as the director of operations of the 28th Bomb Wing at Ellsworth Air Force Base, S.D., he commanded two B-52H Squadrons, and a K-135A and RC-135 Squadron.

Amos still fondly recalls the B-52 mission and close call he had with Jimmy Stewart. “It was a great experience and an honor to have Brig. Gen. Stewart fly with us. He was truly the same gentleman in person as he had portrayed in his many films!”

Brigadier General Jimmy Stewart retired from the Air Force Reserve in 1968, but his Vietnam War experience wasn’t over. In June 1969, Stewart’s 24-year-old stepson, Marine 1st Lt. Ronald McLean, was killed in action when his unit was ambushed while on a reconnaissance patrol near the DMZ.

Warren Thompson has been researching and writing on military aviation history for 40 years and has conducted hundreds of interviews and amassed a collection of thousands of photographs from World War II through Desert Storm.

Jimmy Stewart lost his stepson, Marine 1st Lt. Ron McLean, when the young man was killed in an ambush in the DMZ. Click here to read the story.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.