IT IS ARGUABLY one of the most emotional and impactful scenes in Hollywood history. Sitting at Martini’s bar in the fictional town of Bedford Falls, a forlorn George Bailey has reached his breaking point. Festive music plays in the background as gleeful customers celebrate Christmas Eve. However, the hero of the classic holiday film It’s a Wonderful Life is immune to the merriment. He sits at the bar, nursing a drink and fondling his life insurance policy, a payout of which could cover the lost $8,000 from Bailey Building & Loan. A tight close-up shows Bailey with tears in his eyes as he holds his head in his hands and begins to pray:

“God, God, dear Father in Heaven. I’m not a praying man, but if you’re up there and you can hear me, show me the way. I’m at the end of my rope. I… show me the way, oh God.”

Actor Jimmy Stewart nailed the scene—and then some. He followed the script exactly but then added something extra: the tears. Stewart broke down unexpectedly during the 1946 filming of this memorable moment, about a year after World War II had ended in Europe. Bottled-up feelings poured forth in a rare display of emotion by Stewart, who had already won an Academy Award for Best Actor in 1940’s The Philadelphia Story.

Director Frank Capra was elated with the performance, but he knew he hadn’t captured the scene properly. The cameras were set up for a long shot and Capra wanted to reshoot it with a tight frame on the actor’s face as the tears spilled.

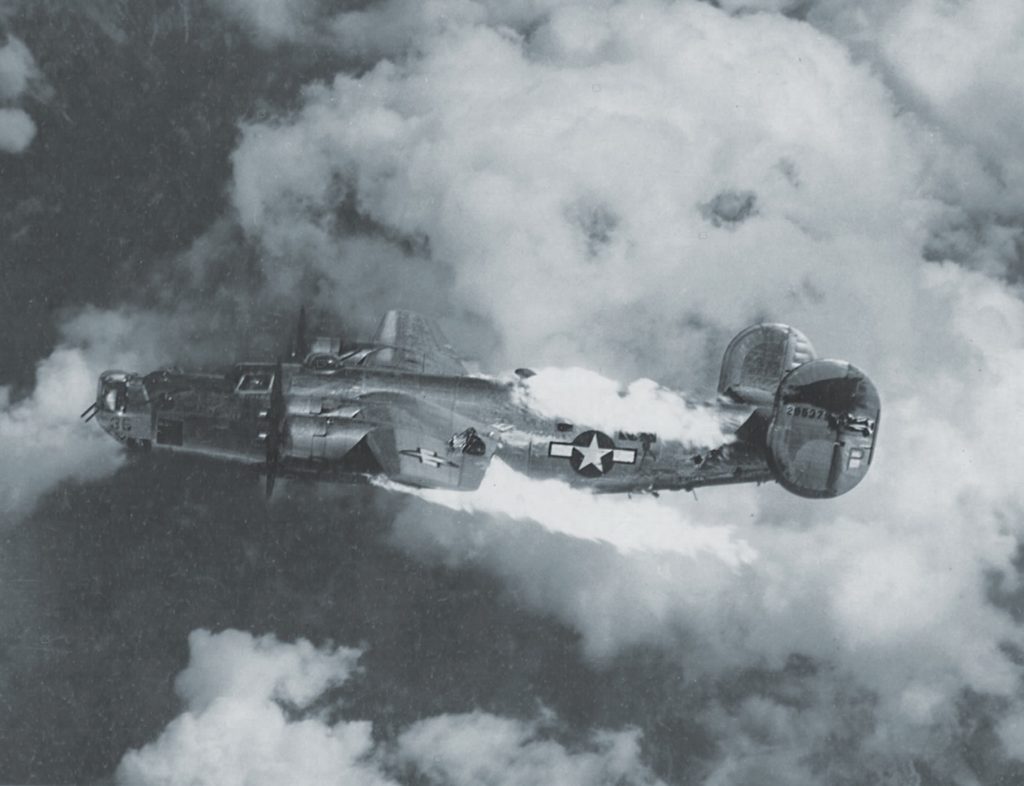

Stewart looked at the director and said, “Frank, I can’t do that again. Don’t ask me.” The actor knew the moment had been spontaneous: he had opened up a reservoir of buried emotions and was unwilling to revisit that dark place in his soul. Although Stewart himself rarely talked about the source of that despair, those close to him knew it came from his combat service as a bomber pilot in World War II. Many noticed the change in him when he returned home after flying 20 missions in Europe in a B-24 Liberator.

Capra would have to find another way to get the scene he wanted.

SOLDIER’S HEART. Shell shock. Battle fatigue. Flak happy. PTSD. As long as humans have fought wars, soldiers have suffered the psychological impact brought on by the horrors of combat. The ancient Greeks even wrote about it in their plays and histories. At the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, Herodotus described how Epizelus “spent the rest of his life in blindness” after witnessing the man next to him killed by a large bearded Persian.

Whatever it is called, Jimmy Stewart most likely suffered from it. “His wife talked about the symptoms of PTSD he had long after the war,” said Robert Matzen, author of the 2016 book Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe. “The nightmares, the sweats, the shakes. He did have to stand down from some rotations because the pressure got to him. In his command position and with the pressure he put on himself as a perfectionist, he just couldn’t stand up to it.”

Fellow actors on the set of It’s a Wonderful Life were concerned by Stewart’s darker side, according to Ben Mankiewicz, a host on Turner Classic Movies and a film critic. “Donna Reed noticed it,” he noted. “She said people were tense. There was definite discussion about playing someone who was that depressed and considering suicide, knowing obviously that was something that was happening across America at the time. Jimmy Stewart was clearly affected by what he went through, and it’s a change we didn’t understand.”

It is well-documented that Stewart suffered nightmares, nervousness, anxiety, and fits of rage after the war. In his book, Matzen evokes the actor’s postwar terrors:

“[T]he nightmares came every night. There he was on oxygen at 20,000 feet with 190s [German fighter planes] zipping past, spraying lead and firing rockets, flak bursting about the cockpit. B-24s hit, burning, spinning out of formation. Bail out! Bail out! Do you see any chutes? How many chutes? Whose ship was it? Oh no, not him! Not them! Bodies, pieces of bodies smacking off the windshield. And the most frequent dream, an explosion under him and the plane lifted by it and the feeling that this was the end. There he was, straddling a hole at his feet big enough to fall through, feeling the thin air at 30 below biting at his skin and swirling as he choked on the stench of gunpowder, looking four miles straight down at Germany.”

After the war, Stewart talked about his service in mostly positive terms and avoided dwelling on the negative. “I saw too much suffering,” he once said. “It’s certainly not something to talk about.” Like so many men of that generation, Stewart would deal with psychological issues that followed him after living through the terror of combat in his own way. “He learned that the anger he had inside of him could be channeled into these dark performances, dark character moments,” Matzen said. “You are looking at the effects of war in some of the scenes in that movie and many other pictures after that. His wife and daughter both said, ‘That’s him in real life.’ He would go from zero to 100 in two seconds. He would fly into a very rare blind rage. That was the war.”

STEWART’S MILITARY CAREER is remarkable, considering how improbable it was. He was 33 when America entered World War II—old by the day’s standards, when most combat pilots were 21 or 22.

He had had a love of airplanes long before he stepped in front of the footlights. He was a licensed pilot and was determined to use those skills with the U.S. Army Air Corps. But his 6-foot-4, rail-thin frame earned him a six-month deferment when he was evaluated for service in the fall of 1940: he was too underweight for his height. He was persistent, though. While trying to get his status changed, Stewart set about getting his transport license as a commercial pilot, figuring that would help offset his age problem: at just shy of 33, he was already over the maximum age for air cadet training. He was at last inducted into the army on March 22, 1941, and assigned to the Air Corps—soon to be the U.S. Army Air Forces. Stewart completed his training in 1942, earned his wings, and piloted B-17 Flying Fortresses as an instructor.

Stewart pushed for a combat assignment and finally got his wish when he was transferred in November 1943 to the 445th Bombardment Group (Heavy). Based at the Royal Air Force airfield Tibenham in Norfolk, England, the unit was part of the VIII Bomber Command, later Eighth Army Air Force, which had been established the year before to conduct daylight bombing raids on strategic targets in Germany. This squadron flew Liberators, so Stewart was checked out on the B-24 after joining the unit.

“Stewart’s commander knew how badly he wanted to get into the war,” said Michael S. Simpson, unit historian for the 445th. “He knew of a B-24 outfit that was in their initial stage of training and needed an operations officer for one of the squadrons. Stewart’s CO asked if they could use an experienced officer, and he got the job.” It wasn’t long before Stewart’s leadership abilities were noticed, and he was made commanding officer of the 445th’s 703rd Bombardment Squadron. He led by example, and his men loved him. Stewart used the laid-back style that he displayed onscreen to get his crews to trust him and follow his orders no matter what.

“His soft drawl was calming to the airmen,” Simpson said. “I talked with several members of the 703rd who said he was a dynamic leader who didn’t need to crack the whip. Once, an enlisted man stole a keg of beer from the officer’s club. They stashed it in their Quonset hut and wrapped it up in blankets. Stewart came in and noticed the pile of blankets. Instead of throwing a fit, he took a canteen cup and poured himself a beer. As he sipped on it, he mentioned that a keg of beer had disappeared, and he knew that none of his men would have taken it. He then finished the beer and walked out of the hut. They couldn’t wait to return the keg!”

Stewart led 11 of the 41 missions the 703rd Bomb Squadron flew against German targets—each of them pressure-filled and dangerous. In 1943 the Eighth Air Force had no long-range fighter protection, so the B-24s were at the mercy of German Me 109s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s as they attacked the formations in deadly waves. Once past the enemy fighters, the Liberators—“widow makers,” as the crews dubbed them—would be pounded mercilessly by exploding flak as they made their bombing runs.

For the Americans, daylight bombing was a meat grinder. Losses were appalling, especially early on in the campaign before defensive tactics were perfected and fighters could escort the bombers to their targets. All told, the Eighth Air Force lost more than 10,500 airplanes, with 26,000 men killed and another 28,000 taken prisoner. By contrast, the U.S. Marines had a total of 23,160 men killed during its bloody island-hopping campaign across the Pacific.

The 703rd Bomb Squadron suffered comparable losses under Stewart’s command. The unit lost 10 aircraft in combat, with 71 men killed in action and 25 taken prisoner. Stewart took each one of those losses personally, compounding the stress he felt in organizing and leading the assaults against Nazi Germany.

Stewart was a perfectionist in many ways, trying to control outcomes with unrealistic expectations. His father, Alex, had been a demanding alcoholic who insisted his son get it right all the time. The pressure Stewart placed on himself to perform was immense. “I prayed I wouldn’t make a mistake,” he later recalled. “When you go up, you’re responsible.”

A few missions, in particular, left a mark on Stewart’s psyche. One was during “Big Week” in February 1944, the attempt by the Allies to knock the Luftwaffe out of the war by bombing airplane factories and luring German fighters to their doom in a costly battle of attrition. The 445th Bomb Group lost 13 of 25 airplanes and 122 airmen. Stewart’s B-24, in which he was copilot and group commander, took a direct hit from an 88 shell, which left a two-foot hole in the fuselage just below the actor’s seat. The damage was so extensive that the Liberator suffered a structural failure when it landed back in England.

While the experience was unsettling, it’s not what Stewart feared the most. His deepest dread was making mistakes that would result in men under his command getting killed—a situation that is almost impossible to avoid in the fog of war. For those who didn’t return, Stewart was often the one who had to write to the families and tell them their loved ones wouldn’t be coming home.

“He felt responsible for these men,” Matzen said. “These were either men in his squadron or that he had trained or were in his formation. Stewart took that so seriously.”

Flak was also a problem on Stewart’s last mission with the 703rd Bomb Squadron. The unit planned to bomb an aircraft engine factory in Basdorf, Germany, but due to weather it was diverted to Berlin, its secondary target. The planes took a beating from antiaircraft fire over the German capital. Michael Simpson’s father, Lieutenant Leland Simpson, was lead bombardier with Stewart that day.

“The strain was really starting to show then,” the historian said. “His commanding officer was concerned Stewart was flying too many missions. When the 453rd Bomb Group lost its group operations officer, it was decided to transfer Stewart, by then a major, to that role. This didn’t mean Stewart would stop flying, just that he would be farther up in the rotation and wouldn’t fly as much.” He went on to fly nine missions as operations officer for the 453rd. Nearly a month later, Stewart’s final mission—his 20th—was a near-disaster. The 453rd Bomb Group almost collided with another, causing several formations to veer away and miss their target: an airfield full of Me 262 jetfighters. Instead, bombs rained down on farm fields and forest.

Quietly, Stewart was told to stand down. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces, let the actor know his services were more important to the Eighth Air Force as an operations officer.

“It wasn’t ever official, but I just told him I didn’t want him to fly any more combat,” Arnold recalled. “He didn’t argue about it.”

THE WAR IN EUROPE ended two months later. “He loved to fly, but he came home after the war vowing to never fly again,” Matzen said. “That’s the toll 20 missions took on him.” Stewart eventually found himself back in Hollywood looking to resume his acting career. The pickings were slim at first, especially for a 38-year-old former star who had been away from moviemaking for five years.

Also working against him was his appearance. Stewart had aged remarkably during the war. Comparing photos of him from when he entered the service and when he left show a much older, wearied individual—someone weighed down by the ravages of command in combat. Back in Hollywood, Stewart was so anxious that he couldn’t keep weight on. His stomach was in knots, and all he could keep down was ice cream and peanut butter. Capra, who had spent the war in the U.S. Army Signal Corps producing a series of films aimed at American troops, approached Stewart with the script for It’s a Wonderful Life. At first Stewart wasn’t interested, but he eventually changed his mind and embraced the project. He had previously worked with Capra on such classics as You Can’t Take It with You (1938) and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Throughout It’s a Wonderful Life, there are glimpses of Stewart revealing the emotions he had tamped down during the war, including the scene in the living room where he explodes while the family is preparing for Christmas. Stewart yells at the children and knocks over gifts and furniture in a fit of rage. Even the aftermath, when he apologizes for his behavior, is uncomfortable to watch.

“Only great actors can tap into those feelings,” Mankiewicz said. “It’s not enough to experience it; you have to have that ability to communicate that to a movie camera. You have to turn it on and capture it. Jimmy Stewart was not a method actor, but he knew intuitively that he was able to find it within himself and translate it for the audience.”

For the scene in Martini’s bar, Capra had planned a long shot to show the action surrounding Stewart. Neither the director nor the actor was prepared for what happened next, as tears poured forth as if from an inner fount.

“As I said those words,” Stewart told Guideposts magazine in 1987, “I felt the loneliness, the hopelessness of people who had nowhere to turn, and my eyes filled with tears. I broke down sobbing. This was not planned at all.”

Afterward, Capra tried to figure out what to do to make Stewart’s grief the key visual for the scene. Since a reshoot was out of the question, he did something that had never been tried before. At great expense, the director had film technicians painstakingly enlarge each frame of the scene one by one—thousands of images in all—until Stewart’s face and his tears filled the screen.

“He created a new process where he simulated the move he wanted to make but couldn’t make,” Matzen said. “Luckily, this is film with a very high quality to start out with. Today, directors can go into the Avid bed [an editing system] and do an optical zoom on computers. That wasn’t possible back then. Capra created a process for simulating the zoom he couldn’t do.”

It’s a Wonderful Life premiered on December 20, 1946. It received mixed reviews and failed to recoup its budget—all the larger because of the special process Capra invented. While the Hollywood Reporter called the film “wonderful entertainment,” New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther found it overly sentimental, although he noted that its star “has grown in spiritual stature as well as in talent during the years he was in the war.”

THE FILM SAT ON A DUSTY SHELF at the studio for decades until, thanks to a lapsed copyright in 1974, it resurfaced to introduce itself to new generations and become a holiday staple on television. It has since been ranked high up on the list of many critics’ favorite films.

“It’s the damnedest thing I’ve ever seen,” Frank Capra told the Wall Street Journal in 1984. “The film has a life of its own now, and I can look at it like I had nothing to do with it. I’m like a parent whose kid grows up to be President. I’m proud…but it’s the kid who did the work.”

Despite his pronouncement about never flying again, Stewart did—and with the military, too. After the war, he joined the Air Force Reserve and was promoted to brigadier general in 1959, becoming the highest-ranking actor in U.S. military history. In 1966, Stewart flew a B-52 mission over North Vietnam as an observer. He retired from the Reserve in 1968.

Of course, Jimmy Stewart also became one of Hollywood’s most endearing and enduring stars. He appeared in 80 movies and was nominated five times for a Best Actor Oscar. He died in 1997 at the age of 89. Two years later, the American Film Institute ranked him third on their list of greatest American actors.

Later in life, Stewart admitted that It’s a Wonderful Life was his favorite movie. The role of George Bailey and that moment in Martini’s bar inexorably changed the arc of his journey and set the stage for even greater things. Says Ben Mankiewicz: “That scene was the beginning of the second act of Stewart’s very lengthy Hollywood career.” ✯

This article was published in the December 2020 issue of World War II.