Facts, information and articles about Jesse James, confederate soldier and famous outlaw from the Wild West

Jesse James Facts

Born: September 5, 1847

Died: April 3, 1882

Spouse: Zerelda Mimms![By R. Uhlman, St. Joseph, Mo. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Jesse_James_dead_01.jpg/256px-Jesse_James_dead_01.jpg)

Jesse James summary: Jesse Woodson James was born into a hardworking family. His parents lived in Clay County Missouri, where Jesse and his two full siblings were born. Robert James, Jesse’s father, was a successful farmer who eventually helped found William Jewell College located in Liberty, Missouri. When Jesse was three years old, his father died in California, preaching to those looking for gold. Jesse’s mother remarried.

During the Civil War, Jesse and his family were dedicated Confederates. When he was sixteen, his brother has already joined the Confederate Army. As his brother’s company lodged in Clay County, Missouri, Jesse took the opportunity to enlist in Taylor’s company. In 1864, Jesse and Frank joined Bloody Bill Anderson, the leader of a group of bushwhackers. They had a reputation of cruel and brutal treatment of Union soldiers, and Jesse was identified as one of the members who took part in the Centralia Massacre that left 22 unarmed Union soldiers dead or injured. As punishment, all family members of Jesse and Frank James had to leave Clay County. Jesse later married his first cousin, Zerelda Mimms, who was named after Jesse’s own mother. They had two children together, Jesse E. James and Mary James Barr.

After the Civil War ended, Jesse and Frank made their living robbing stagecoaches, banks and trains. On April 3, 1882, Jesse was shot to death be a member of his own gang. The lure of collecting reward money was far stronger than any loyalty he had to Jesse James, it appears. Some moviemakers have romanticized Jesse James as taking from the wealthy and sharing with the poor. This is purely fiction.

Articles Featuring Jesse James From HistoryNet Magazines

Featured Article

Jesse James’s Assassination and the Ford Boys

The house at 1318 Lafayette St. in St. Joseph, Missouri, was a one-story white wood cottage with green shutters, sitting in a lot on the brow of a hill overlooking the town. It was Monday, April 3, 1882, and over breakfast the man who rented the house, who was going by the name Thomas Howard, commented on a newspaper article about the surrender of Jesse James Gang member Dick Liddil to Missouri authorities. Liddil was a traitor and ought to be hanged, he said. There was considerable unease among the two guests, brothers Charlie and Bob Ford, but they pretended not to care.

After breakfast, Mr. Howard and Charlie Ford went to a stable behind the house to curry the horses. Upon returning to the house, the two men entered the living room. “It’s an awfully hot day,” said Howard, pulling off his coat and vest and tossing them aside. “I guess I will take off my pistols,” he continued, explaining that he didn’t want anyone who might be walking by outside to look through the window and see him armed. He picked up a feather duster and stepped up on a chair to clean some pictures on the wall. Bob and Charlie quickly moved between Howard and his guns, Charlie giving a wink to Bob. Both drew revolvers on the man on the chair, now with his back turned. Hearing the click of a weapon being cocked, Howard started to turn his head, and then the report of Bob’s six-shooter reverberated through the house. Charlie didn’t even bother to fire but lowered his gun as the man fell to the floor, with a bullet in his skull.

Howard’s wife rushed into the room, and the brothers tried to explain that the six-shooter had accidentally gone off. “Yes,” the wife said as she bent over her husband’s corpse, “I guess it went off on purpose.” The Fords dashed to the telegraph office down the way and sent messages to Clay County Sheriff Henry Timberlake, Kansas City Police Commissioner Henry H. Craig and Missouri Governor Thomas Crittenden. Last, they used a newfangled device known as a telephone to call the office of City Marshal Enos Craig. Thomas Howard, the man they had killed, had earlier used the alias John Davis “Dave” Howard, among others. But his real name was Jesse James.

GETTING ACQUAINTED

The Ford boys first became acquainted with outlaw Jesse James in the summer of 1879. Jesse had been living in Tennessee since 1877, trying to “go straight” following the disastrous attempt to rob the Bank of Northfield, Minn., the year before. While his older brother Frank made the transition to peaceful citizen, Jesse suffered from malaria and found it difficult to adjust to honest work. He returned to Missouri to put together a new gang and in the process crossed paths with the Fords. James T. and John Ford, the father and brother of Bob and Charlie, had served in Virginia under Colonel John Singleton Mosby, the legendary “Gray Ghost” of the Confederacy, and were fellow guerrillas. Jesse, who had served under guerrilla leaders William Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson, probably swapped more than a few war stories on his occasional visits. Jesse liked to at least maintain the pretense of being harassed by former Unionists in order to obtain food, shelter and information from ex-Confederates while he was on the dodge.

One of the recruits to this new outfit was Ed Miller, whose brother Clell had been killed in the September 1876 Northfield raid. Miller knew the Fords, and it was Miller who first brought Jesse to the Ford house, the Harbison place, outside the town of Richmond, in Missouri’s Ray County. In the summer of 1880, Jesse and Miller had a falling out. The exact details are unclear, but it appears that Ed wanted to leave the gang, and Jesse got the notion he was going to be betrayed and fatally shot Miller. Jesse turned up at the Harbison place with Miller’s horse, which he left there, telling Charlie Ford that Ed had become ill and had gone down to Hot Springs, Ark. Enter Jim Cummins, a former guerrilla comrade of Jesse’s. Jim’s sister Artella had married Bill Ford, uncle of Bob and Charlie. The couple now lived at the old Cummins place in Clay County, a few miles from the James farm. Cummins became suspicious that something bad had happened and tried to locate Miller. A trip to Nashville, Tenn., where Jesse was living, in the winter of 1880-81, brought similar suspicions on Cummins, when he started asking too many questions. He fled in the night to avoid a likely bullet from Jesse.

On Friday evening, March 25, 1881, almost two weeks following the robbery of a Corps of Engineers payroll at Muscle Shoals, Ala., gang member Bill Ryan became drunk at a small store a few miles north of Nashville. Brandishing a revolver, he claimed to be Tom Hill, “outlaw against State, County, and the United States Government.” He was soon taken into custody. On his person was found some of the Muscle Shoals loot, and he was quickly lodged in the Nashville calaboose. Clearly, Jesse’s choice of gang members left a lot to be desired. It would only get worse.

The bad news about Ryan arrived via the local newspapers, and Frank, Jesse, their respective families and gang member Dick Liddil were soon beating a hasty retreat to Kentucky, with the law on their tail. Soon that state was getting too hot, and they decided to go back to Missouri. Jesse saw this as a chance to lure his now unemployed brother Frank back into the holdup business. He also wanted to keep an eye on legal proceedings against Ryan, who was extradited to Independence, Mo., in June, to be tried for his part in the Glendale train robbery, and to follow up leads on Jim Cummins.

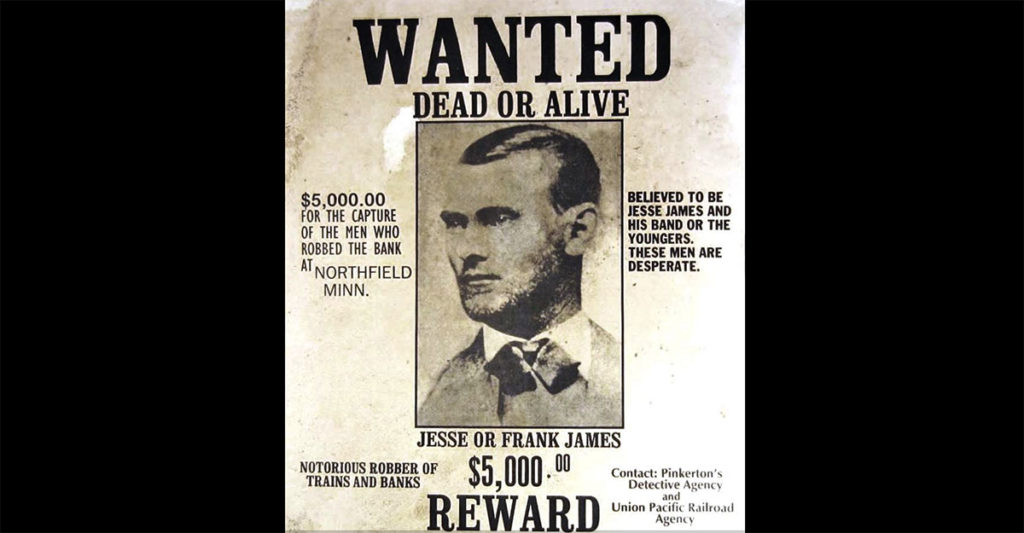

Jesse soon settled in Kansas City, and was planning a raid on the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad somewhere near Gallatin, Mo. It was said that the trains brought large sums of cash to the Farmer’s Exchange Bank there twice a week. On the evening of July 15, 1881, the gang struck near the whistle stop at Winston. Conductor William Westfall was killed in the process. It was later said that Westfall had been on the train that took Pinkerton detectives on their 1875 raid on the James farm, but this was apparently not known at the time. The crime created a sensation in the press. Governor Thomas T. Crittenden, who had vowed to rid the state of the James Gang in his campaign the year before, held a meeting in St. Louis with railroad and express company executives, who promised a collective reward of $50,000 to put the gang out of business. Frank and Jesse had a reward of $5,000 each on their heads for their capture and delivery to authorities, with another $5,000 on conviction. There was no mention of it being dead or alive. Handbills were printed to this effect, though in later years counterfeit “Dead or Alive” posters would be marketed to unwary tourists.

Following the Winston robbery, the gang scattered. Dick Liddil spent a good bit of time at the Harbison place with the Fords, and the brothers were reportedly initiated into the holdup business in August 1881. Liddil, a convicted horse thief prior to joining Jesse’s new gang in 1879, took Charlie Ford with him to rob a stage running between Excelsior Springs and Vibbard. The driver was hauling just one passenger. “Charlie made them stand and I made them deliver,” Liddil recalled in his later confession, the take being a whopping $30. About a week later, Liddil put together another sub-gang consisting of himself, Jesse’s cousin Wood Hite, and Bob and Charlie Ford. On Thursday evening, August 25, they robbed a man with a wagon of $20 to $30 halfway between Lexington and the railroad junction at North Lexington. They tied up their victim and continued to wait for other prey. About five minutes later, they halted a stage with seven passengers, six men and a woman.

“All of you hold up your hands and get out of there,” one of the outlaws commanded. Bob and Wood held double-barreled shotguns on the men after they stepped down, while Dick and Charlie, armed with revolvers, relieved them of around $200 and several watches. All the bandits wore blue masks. The woman, a Miss Hunt from St. Joseph, was allowed to remain in the coach and to keep her valuables. One of the victims, C.W. Horner of Appleton City, a cripple studying for the ministry, was relieved of $52. Oddly, it was the same stage driver, a Mr. Gibson, who had been robbed by the James-Younger Gang seven years before, almost to the day, near the same place.

MORE PLANS FOR JESSE

Meanwhile, Jesse James had other plans afoot. Gang member Bill Ryan was being held in jail in Independence to face trial for the robbery of the Chicago & Alton at Glendale. Jesse would kill two birds with one stone—rob the railroad again, not far from the same spot; and at the same time intimidate railroad employees, some of whom might testify at Ryan’s trial. On Wednesday night, September 7, 1881, six years to the day after the Northfield robbery attempt, the James Gang went to work at a 30-foot chasm along a curve known as Blue Cut. The trains were known to slow down at this point, and men could be placed along the rim of the cut to cover the proceedings below.

A masked man was placed on the track, beside a pile of rocks, where he waved a lantern to get the oncoming westbound locomotive to halt. Wood Hite and Charlie Ford were to take the engine and express car. A few blows to the door by the now captive engineer were enough to open the latter, and the agent for the U.S. Express, who had slipped out, was coerced to return with threats on the engineer’s life. This and a perceived slowness at opening the safe caused Charlie Ford to pistol-whip the clerk. Less than $400 was found inside, and Ford gave the man another whack for good measure.

Little did the bandits know that an Adams Express safe, hidden under a pile of chicken coops, contained more cash. Frustrated, the outlaws proceeded to rob the passengers. The whole affair lasted about half an hour. Before leaving, one of the outlaws, thought to be Jesse, shook hands with engineer “Chappy” Foote, gave him $2 and told him to “spend it on the boys.” The outlaw then warned Foote: “You’d better quit running this road. We’re going to make it so hot for this damned Alton road they can’t run.” Newspaper accounts reported the anguished passengers’ arrival at the Union Depot in Kansas City. Many had lost every cent they had and were stranded.

In the latter part of September, Ryan went on trial in Independence. An official of the Chicago & Alton told Jackson County prosecutor William Wallace that his superiors didn’t think any of the gang could be convicted in Missouri but that if Ryan was convicted, the railroad might be singled out for further raids. He asked Wallace not to call any railroad men as witnesses. During the course of the trial, some of Ryan’s friends, fully armed, hovered ominously about the courthouse.

Wallace’s key witness was former gang member Tucker Bassham, convicted and sentenced to 10 years for participation in the Glendale heist. Crittenden offered him a full pardon for his testimony. Ryan was found guilty and sentenced to 25 years in prison. There was talk of a possible rescue attempt, but the old jail was built like a fortress, and the prisoner was guarded by Captain M.M. Langhorne, described as “one of the coolest, gamest men” of Joe Shelby’s former Confederate Brigade. Several other guards were also former Confederates, and even prosecutor Wallace had been forced to relocate with his family during the war after their homestead was ransacked by Kansas jayhawkers. “The jury that convicted Ryan broke the back of outlawry in the state of Missouri,”commented Wallace. “Thousands of mouths that had been locked by fear were opened….”

DEATH OF A FIRST COUSIN

Sometime in the fall of 1881, Jesse James resumed his pursuit of Jim Cummins. This took him to the home of Bill Ford, whose wife was Cummins’ sister. In an effort to get information on Cummins’ location, Jesse roughed-up Samuel Ford, 15-year-old first cousin of Bob and Charlie. It was a bad mistake. John W. Shouse, a neighbor who lived about a mile or so from the James farm, was a fellow Southern sympathizer who was also getting tired of the brigandage. When he learned of what had happened to the Ford boy, he enlisted several neighbors who were armed and went on the watch for Jesse. It was around this time that Bill Ford and William Wysong, one of the neighbors of Shouse, brought Bob Ford into the fold.

Meanwhile, Dick Liddil, during a trip to Kentucky, got into an argument with Wood Hite, first cousin of Frank and Jesse James. Liddil was said to be having an affair with Hite’s stepmother. It all culminated in a shootout at the Harbison place on December 4, 1881, with Hite and Liddil firing at each other and then Bob Ford joining the fray. Ford fired one shot at Hite, which he would claim was the fatal bullet. In fact, Liddil had shot Hite as well, and it’s still unclear who deserved credit for the killing. Both, however, would be considered equally guilty if Jesse only knew.

An arrangement was made for Bob Ford to meet Governor Crittenden on January 12, 1882, in Kansas City. While Bob would later claim that he struck a deal to get Jesse “dead or alive,” both his brother Charlie and the governor later denied this. It was for the “capture” of Jesse. Bob was to coordinate with Shouse, Wysong and other neighbors, as well as Sheriff Timberlake of Clay County and Police Commissioner Craig of Kansas City. “There was no sort of bargain about his receiving a portion of the reward and a pardon if he would kill Jesse James,” Crittenden later said. “It was of course known that the outlaw had sworn never to be taken alive, and men who went in search of him were acquainted with this fact.” If you went after Jesse you took your own chances. Dick Liddil decided not to risk it. On January 24, he secretly surrendered to authorities and soon helped Craig and Timberlake capture Clarence Hite, Wood’s brother. Clarence was taken without a fight (and without extradition papers) at his home near Adairville, Ky., on February 11 and hustled back to Missouri by rail to answer for his role in the Winston and Blue Cut robberies.

Time was running out for Jesse James. “He said he expected to be a bandit as long as he lived,” recalled Charlie Ford, who had helped Jesse move from Kansas City to St. Joseph in November 1881 and lived with Jesse and his family. In early March 1882, Charlie accompanied Jesse in casing a number of banks in northeast Kansas. Jesse asked Charlie if he knew of any possible recruits to help with future robberies. Charlie suggested his brother Bob. After looking over likely targets, Jesse and Charlie headed back to pick up Bob. On the day of the killing, April 3, Jesse had talked of leaving for Platte City, to rob the bank there the following day. A trial was in progress, and he felt this would distract the local population. The Fords wondered if he hadn’t suspected them after reading about Liddil and would try to gun them down as he had Ed Miller, out in the middle of nowhere.

The reaction of Commissioner Craig and Sheriff Timberlake to the news of Jesse’s death was mixed. “Hurrah for you,” telegraphed Craig, who said he was coming to St. Joseph. Timberlake, on the other hand, had expected to be in on the capture and to have a piece of the reward. According to one of his deputies, the news of Jesse’s killing “was a dampener.” Timberlake, who had served in the Confederate Army and knew Jesse from before his days as an outlaw, identified the body, as did others who passed through the funeral parlor where the corpse was displayed and photographed. The body bore wounds from the Civil War that matched those carried by Jesse James. Jesse’s death had been reported at least as early as late 1879, when a hoax was perpetrated by former gang member George Shepherd, who claimed he had killed the bandit in a shootout in southwest Missouri. Authorities wanted to be sure they had their man. In fact, on April 4, the day after the shooting, the Los Angeles Times raised the doubts in an editorial comment. “Jesse James is like a cat; he has been killed a great many times, only to as often enjoy a resurrection.” The Boston Globe had a rebuttal two days later, “Any Western reporter who now resurrects Jesse James ought to be shot.”

AFTER THE ASSASSINATION

Indeed there had been a full coroner’s inquest, an autopsy and photographs taken of the corpse. The body was taken to Kearney, Mo., for burial in the yard at the farm where Jesse had been born. The Fords had been taken into custody and lodged in jail. Wood Hite’s body was dug from the Harbison place when someone got the idea that there was a reward, only to discover that, as with Jesse, it was for his capture. Bob and Charlie were arraigned on charges of first-degree murder on April 17, 1882, and sentenced to hang after both pleaded guilty, but they were pardoned that same afternoon by Governor Crittenden. If the Ford brothers had expected any reward money, though, they were most likely disappointed. There was considerable commotion over the killing of Jesse for the next several months as newspapers found that, in death as well as life, he could sell papers.

But that wasn’t all. Jesse’s widow, Zee, had to support herself and her two children—6-year-old Jesse Edwards and 2-year-old Mary Susan—and was forced to sell some personal effects at the house in St. Joseph, including the family dog. Ten cents admission was charged to visit the house, and souvenir hunters reportedly made off with almost as much as they bought, chipping off pieces of the fence, house and outbuildings. Henrietta Saltzman, owner of the house, would sue Missouri and Governor Crittenden, claiming that the killing was the work of state agents. Mrs. Saltzman had been renting the house for $14 a month to Jesse James, but a few weeks after his death, she moved back and began charging visitors a quarter a head to visit the place, now replete with bullet hole in the wall. Over the next year and a half, she would make a killing. A reporter who visited the house in September 1883 estimated that she had made, between admission charged to thousands of visitors and splinters of wood sold as mementoes, $1,500 off the house as a tourist attraction. The reporter also noted that there were some 50 “bullets that killed Jesse James” floating around. Never mind that the slug had never exited the head and had been pulled out of Jesse’s brain during the autopsy.

Bob and Charlie Ford were lured to the stage, and by early August 1882 were in Chicago playing what was described as a “State Street dive.” The brothers considered moving on to Cincinnati, but instead took their act to Chicago’s Park Theater, where they began to do a depiction of the killing of Jesse James. At the end of the month, Bob was arrested for disorderly conduct and carrying concealed weapons. From Chicago the Fords moved on to New York, playing Brooklyn in late September. At Bunnell’s Museum, they were occupying a spot in Curiosity Hall when a woman thought by Bob to be Frank James’ wife appeared and sent panic through the brothers. The boys decided to move on to the Broadway Museum, which they played through the first week in October.

Bob Ford was due back in Missouri that month for trial at Plattsburg on charges of murdering Wood Hite. The jury brought in a not guilty verdict on the 26th, and Bob and Charlie again left to pursue their career on the stage in the East. On December 21, they were slated to give “a descriptive lecture” at Hartford, Conn., in Allyn Hall, but the door receipts amounted to only $2 and the appearance was cancelled. Next stop Boston, where the brothers played the Dime Museum at Horticultural Hall. This institution, which billed itself as a “select family resort for ladies and children,” was reported to be “packed to suffocation” for the Fords’ appearance, at a dime a head.

The boys had just been introduced to the crowd when a young man in the front row, thought to be intoxicated, called the Fords “damned cowards.” Charlie was restrained from jumping off the stage, but there were other remarks, and the manager, somewhat indignant himself, allowed the boys to go into the audience. Guns were reportedly drawn and two men were pistol whipped. The audience stampeded, a woman screamed and fainted and a large group smashed a window to escape, while others surrounded the Ford boys. A police officer named Robinson led half a dozen other policemen to the building, and they were about to haul the boys off when the manager intervened. He begged the police to charge the Fords later, and he would vouch for them to appear. The police agreed, and the Fords made their later performances at the Dime Museum. There were some hisses from the crowd, and the atmosphere was tense, but the show went on to conclusion without further outbursts. A Chicago Daily Tribune editorial commented that it was “a grave mistake…in allowing them any greater freedom than a comfortable cell affords.” A few days later, after the brothers had jumped bail and left Boston, the Boston Globe commented that “but for the undesirableness of the presence of the Fords in the city under any circumstances,” the paper would suggest that Officer Robinson be made to find, arrest and return the Fords at his own expense. But their checkered career on the stage had a year further to run, in which time they threatened the manager of the National Theater of Philadelphia, who sarcastically replied via mail that he had an opening for them in July 1982, nearly a century later, if they wished to play there.

Meanwhile, on the evening of July 2, 1883, Charlie Ford left his pistol in a Kansas City saloon, and when barkeep George Wampel pointed it at a patron named Webster, the gun accidentally went off, killing the teamster. A month later, Charlie was arrested and charged with participation in the 1881 Blue Cut train robbery, but he made the $5,000 bond. He claimed in the press that he was working with local lawmen to infiltrate the James Gang at the time, but Sheriff Timberlake, Commissioner Craig and Governor Crittenden were dumbfounded by his statement. On September 20, the Fords appeared in a Louisville, Ky., variety house, in what was called The Brother’s Vow; or, The Bandit’s Revenge. They were hissed and hooted by the audience at the point where Bob killed Jesse.

In addition to Blue Cut, Charlie had been charged with the 1881 stage robbery north of Lexington, and was to go on trial in Richmond on November 23, but apparently a continuance was granted in the case, which had been brought by Jesse James’ widow and mother, in an attempt at revenge. The stage career of the Fords ended in St. Louis in January 1884. Charlie, suffering from tuberculosis and addicted to morphine, shot himself. He had forfeited bond in the Richmond case, having failed to appear in court. Bob Ford would move west to Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory, where he operated a saloon briefly with Dick Liddil and had an equally lackluster career as a policeman. Finally settling in Creede, Colo., where he ran another saloon, the man who shot Jesse James was gunned down on June 8, 1892, by Ed O’Kelley, with a sawed-off shotgun. Although O’Kelley might have had other reasons for murdering the unpopular Ford, one possible motive was that while growing up in Missouri, O’Kelley had viewed the notorious Jesse James as a hero.

This article was written by Ted P. Yeatman. Ted Yeatman is considered one of the nation’s foremost authorities on the James brothers. This article originally appeared in the December 2006 issue of Wild West magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!

Featured Article

Jesse James and the Gads Hill Train Holdup

Five armed riders wearing U.S. Army overcoats stopped to have their horses shod at a village blacksmith shop on the Chalk Bluff Road in northeastern Arkansas on Tuesday, January 27, 1874. They were strangers to the area, and the bedrolls, extra clothing and other gear behind their saddles indicated they were traveling men. What’s more, each man wore several Colt Navy revolvers, three carried double-barreled shotguns, and their horses, although of superior quality, were noticeably jaded from hard riding. The blacksmith asked no questions but went straight to work. When he finished shoeing the animals, the travelers paid him and rode on.

Only later would the smithy learn a shocking truth about his mysterious patrons. Newspapers reported that they were Missouri outlaws, former Confederate guerrillas, fresh from a stagecoach holdup committed January 15 near Hot Springs, Ark. Even more disturbing were their suspected identities. Calling them “the most daring band of robbers the country ever contained,” the St. Louis Dispatch expressed “very little doubt” that they were members of the infamous James-Younger Gang, consisting that day of Frank and Jesse James, Arthur McCoy and two of the Younger brothers.

Soon after leaving the blacksmith shop, the “daring band” crossed the state line into Missouri and proceeded north along the St. Louis & Iron Mountain railroad tracks. Jesse James and his gang, it seems, had one more bit of illicit business to attend to before making the long ride back home to St. Clair and Clay counties. They were planning to rob a train—something never done before in Missouri.

Gads Hill, according to one contemporary observer, was a “small place, of no account.” Situated in the piney Ozark wilderness of southeastern Missouri, 120 rail miles south of St. Louis, the tiny settlement contained only about 15 people, three crude houses, a store/post office and a small railroad platform. Passing trains generally only slackened speed there to exchange mailbags, but today would be different.

On this chilly Saturday afternoon, January 31, 1874, the southbound Little Rock Express was scheduled to stop and put down a passenger—State Rep. L.M. Farris of adjoining Reynolds County. His 16-year-old son, Billy, had just arrived with team and wagon to meet him and was inside the store warming himself at the stove. Also present in the store were several men who had dropped by to chat with the storekeeper and station agent Tom Fitz. The village women were in their homes attending to chores, and their children were outside playing. The time was nearing 3 p.m., and all was well—or so everyone thought.

As the children played by the roadside, the five armed riders approached from the southeast. The men’s hats were pulled low, and their faces were hidden by white hoodlike masks with triangular-cut eyeholes. When young Ami Dean glanced up and saw these frightful-looking creatures, he ran for home, crying. “Don’t be afraid, little boy,” he later recalled one of them hollering. “We won’t hurt you.”

The gun-toting intruders quickly robbed the storekeeper of a fine rifle and a reported $700 or $800 he kept in his coat pockets. Fortunately they missed another $450 that had slipped down in the lining of his coat. After rousting all citizens from the store and houses, the outlaws helped them build a large bonfire to ward off the cold. One of the masked men then went to work prying open the railroad switches. Their plan was to force the expected train onto the sidetrack. After this was done, everyone—men, women, children of the community and outlaws—sat back for a long wait.

Finally, at 4:45 p.m., running about 40 minutes behind schedule, the little four-car train and its 25 passengers topped the grade and approached Gads Hill. Hearing the engineer whistle for “down brakes,” conductor Chauncey Alford walked to a door between cars and looked forward over the side. What he saw chilled his bones. A man was standing on the station platform waving a red flag, a railroad signal for “danger ahead.” Worse, the man was masked. Alford had the safety of his passengers to worry about, so he jumped off the slow-moving train and ran toward the flag-waver to find out what was going on. As he did, he noticed the train switch onto the sidetrack. At the same moment, three other masked men crawled from under the platform and a fifth emerged on the other side of the tracks. Seizing Alford by his collar, one of them shouted, “Stand still, or I’ll blow the top of your damned head off!”

Young Billy Farris stood with the others at the bonfire until he saw his father appear in the doorway of one of the cars. Then, ignoring the armed guard, he ran to L.M. Farris, shouting that the train was being robbed and he should step off on the side where the villagers were. Farris did so, and he was not robbed.

As the train stopped, two of the outlaws ran forward and forced the engineer and fireman off the locomotive. Several curious passengers and trainmen stepped out on the platforms between cars, and others leaned out of windows. A masked man armed with a double-barreled shotgun shouted, “Take those heads back again, or you’ll lose ’em!” Another, brandishing a revolver in each hand, ran along the opposite side of the train, warning that the conductor and engineer would be shot if anyone attempted to interfere.

The other three outlaws climbed aboard the combination mail-baggage-express car. They rifled the contents of the express safe and registered-mail packages; then two of them stepped off. The one remaining asked express agent Bill Wilson for his receipt book. Apparently he wanted to bring the records up to date. Opening the book and turning to a blank page, the thief mischievously wrote, “Robbed at Gads Hill.”

The robbers forced Wilson to join his fellow crewmen on the platform. Then, some of the former guerrillas moved to the passenger cars. At first they announced they would only rob the “sons of bitches” who wore high silk hats (or plug hats, as they called them), but they soon added they would also rob “Goddamned Yankees,” regardless of their hat styles. Capitalists—men who came by their money easily —were also on their hit list. “Workingmen” and ladies would be spared. The bandits began examining the palms of male passengers. Men with soft hands were robbed; men with calloused hands were not. A minister, who was passed by when he told them his profession, asked if the outlaws might stop a moment so he could pray for them. “We hain’t time,” the leader responded, but then added, “You pray for us tonight…that we may all get to the good country.”

The passengers’ fears were eased somewhat by the light-hearted behavior of their abductors. As the masked men walked the aisle, they made jokes, patted the heads of children and bowed politely to the ladies. One of them exchanged his battered slouch hat for the much finer hat of a well-dressed gentleman. When a rather intoxicated Irishman offered his flask and said, “Won’t you have a drink, boys?” the leader answered with a chuckle, “No, sir, I’m afraid you might have it spiked.” But it wasn’t all fun and games. The robbers seemed to think that a famous Chicago detective was aboard and repeatedly asked, “Where’s Mr. Pinkerton?” For two-and-a-half years, Allan Pinkerton and his Pinkerton National Detective Agency had been ardent pursuers of the James-Younger Gang, and the outlaws were apparently intent on doing him in. Several male passengers suspected of being the sleuth were threatened. One was even taken to a private compartment and strip-searched for a Pinkerton “secret mark.” All proved their identities and lived to travel another day.

Just before stepping off the coach, the robber who had requested prayer from the preacher turned and spouted a few lines of William Shakespeare. Although it was never reported what lines he quoted, they may have been from King Henry IV. In that play, the bard used Gad’s Hill, England, after which the Missouri village (without the apostrophe) was named, as a setting for a highway robbery pulled off by Sir John Falstaff and friends. It has been suggested that perhaps Frank James’ love for that play—or Shakespeare in general—was a determining factor in the selection of Gads Hill, Mo., as the robbery site.

The wealthiest passengers were in the Pullman car. Among those to hand over his money was a despised, soft-handed, plug-hatted Minnesotan who had the misfortune of being named Lincoln. “Any Goddamned son of a bitch [with] that name ought to be shot!” one of them growled. John F. Lincoln was, by one account, robbed of about $200, and when his hat (accidentally?) fell to the floor, the bandit gave it a swift kick. Lincoln later voiced a strong opinion that this particular robber was Cole Younger.

Also aboard this coach was James H. Morley, chief engineer of the Cairo & Fulton Railroad, a St. Louis & Iron Mountain subsidiary. When Morley stood up and protested the robbery of the company for which he worked, a revolver was placed under his nose. “Sit down, shut your head, and mind your business,” he was told. Had the gunman known that Morley indeed was minding his business, it wouldn’t have mattered. The railroad executive still would have been fleeced of $15. Morley’s wife was not robbed, but when they came to another woman in the car, the rules suddenly changed. A Mrs. Scott was traveling from Pittsburgh to Hot Springs, Ark., with her young son and carrying the hefty sum of $400.10. When she presented the money, the noble bandits apparently forgot their promise to not rob ladies and took all but the dime.

At last, satisfied they had gotten all the desired monies and valuables from the train, one of the thieves walked back to John Lincoln and handed him a piece of paper. On it was scribbled a detailed account of the train holdup, complete with a headline. The outlaw said he had written it for the newspapers to make sure that this time they reported the facts correctly. It read:

THE MOST DARING

ROBBERY ON RECORDThe southbound train on the Iron Mountain railroad was boarded here this evening by five heavily armed men and robbed of ______ dollars. The robbers arrived at the station a few minutes before the arrival of the train and arrested the agent and put him under a guard and then threw the train on the switch.

The robbers were all large men, none of them under six feet tall. They were all masked and started in a southerly direction after they had robbed the express. They were all mounted on fine blooded horses. There’s a hell of an excitement in this part of the country.

Lincoln turned the article over to conductor Alford, and, although not entirely accurate, it would later appear in several newspapers as part of their coverage of the crime.

The amount stolen from the train was never reported with certainty, but Alford, who should have known, stated that the bandits made off with $2,500, four registered money packages (one of which contained $2,000), a gold watch, five pistols, one ring and a diamond stick pin. Newspaper estimates ranged from $2,000 to $22,000.

Having completed the heist, the outlaws paused to shake hands with the engineer and thank him for his hospitality. Alford and another crewman went to close the switches, and while this was being done, the robbers galloped away. Besides money and valuables taken from the train, they also stole three fine saddle horses from the village.

Alford was happy to finally have his train rolling again. At Piedmont, seven miles south, he reported the robbery by telegraph to the Iron Mountain headquarters in St. Louis. From there the news spread like wildfire. Indeed a “hell of an excitement” had been orchestrated in Missouri, and at least a stir would be felt across the nation.

On Sunday morning, a posse of 25 armed horsemen set out in pursuit of the villains. Others joined in along the way. Although a slight snowstorm had occurred during the night, the possemen had little trouble following the trail. The retreating gang, it was discovered, had forded Black River six miles northwest of Gads Hill and then taken the Lesterville road north to the three forks. On Middle Fork, the posse recovered a spent horse. It was one of those stolen at Gads Hill and reportedly belonged to a member of the posse.

As was the custom among traveling horsemen of the day, Jesse James and his friends often stopped for food and lodging at farmhouses. Stories of some of those visits were reported in contemporary newspapers; others have been handed down. In all instances, according to news accounts, “they behaved very genteelly” and paid all their bills “lavishly.”

The train robbers proceeded along Black River until they came to its West Fork. Turning west, they followed that stream into northwestern Reynolds County. By then they were badly in need of fresh horses. The Salem Success reported, “In one instance they paid $130 for a horse and shot one they were riding, substituting the fresh one.” The newspaper may have been referring to an incident that is said to have happened one night near the confluence of West Fork and Tom’s Creek. There the gang had supposedly stopped at the farmhouse of James and Elizabeth Sutterfield and asked to buy a horse, as one of theirs was worn out. Should he refuse to sell, they told James Sutterfield, they would take the horse anyway. Sutterfield had little choice, and the deal was made. After saddling the fresh mount, the buyer drew a revolver and shot the jaded horse in the head. As it fell kicking in the barnyard, the strangers rode away. The next morning, Sutterfield went out to bury the animal and was shocked to find it still alive. With proper care the wounded horse eventually recovered and lived on the farm for many years as a local celebrity.

Jesse James and his gang continued across the state and Tuesday night stayed at the home of a widow named Cook, who lived on Current River about one-half mile above the mouth of Gladden Creek. Two of them appeared to be brothers, Mrs. Cook later said, “being very much alike in form and face.” They left at 4 o’clock the next morning and, according to the widow, went two abreast about 100 yards apart, the odd man riding last and leading a spare horse. Some two miles upstream, near a gristmill at Welch Spring, they forded the river and proceeded across Texas County to Big Piney River. Along the way they continued their practice of paying farmers for food and shelter. Horses, though, were usually “borrowed.”

Their next reported stop was at the Mason farm, where they arrived Wednesday evening. Dexter Mason, soon to be elected state representative, was in Jefferson City, but his wife agreed to feed the travelers and put them up for the night. Sometime after they left the next morning, three farmers rode up in search of thieves who had stolen their horses. Mrs. Mason, already suspicious of her house guests, was now virtually certain she had entertained the robbers of Gads Hill.

Also still in pursuit was the main posse, although it was rapidly losing enthusiasm and members. When the men left the trail Thursday evening and rode up to Licking for a much-needed night’s rest, there were only 11 remaining—and they, too, soon admitted defeat and headed home.

By now reported sightings of the long riders were becoming fewer. On the morning of February 12, they were spotted about three miles northeast of Phillipsburg crossing the railroad tracks at Brush Creek. Then, at shortly past midnight on February 18, a Bolivar couple was awakened by the sound of passing horses and from their bedroom window observed five men of the outlaws’ descriptions riding down the street. A newspaper supposed they were bound for nearby St. Clair County, where the Younger brothers often stayed with friends.

It is indeed likely that the Youngers did stop in St. Clair County, while Frank and Jesse (and perhaps the fifth man) continued on to their mother’s farm near Kearney in Clay County. When they arrived there during the first week of March, Allan Pinkerton already had agents en route. Among them were Joseph W. Whicher, assigned to locate the Jameses, and Louis J. Lull and John H. Boyle, assigned to hunt the Youngers.

On the evening of March 10, Detective Whicher arrived at Kearney by train. Posing as a farm laborer in search of work, he naively believed he could outwit and single-handedly capture the James brothers on their home turf. That night he set out on foot for the James farm. The next morning his lifeless body, shot in the head, neck and shoulder, was found along a roadside in neighboring Jackson County. One week later, Lull, Boyle and a hired guide, part-time Deputy Sheriff Edwin B. Daniels, were accosted by Jim and John Younger on a road near Roscoe in St. Clair County and a deadly gunfight ensued. Cole Younger later claimed his brothers had stopped the detectives only to explain that they were innocent of the Gads Hill affair, and had Lull not overreacted, no one would have been harmed. As it was, John Younger, Daniels and Lull all died from their wounds.

Some months passed and Allan Pinkerton, still bitter over the deaths of his agents, sent a squad of detectives by special train to Clay County with orders to capture the elusive James brothers and burn down their mother’s home. At shortly past midnight on January 26, 1875, the Pinkerton men and a neighboring farmer, Daniel Askew, attempted to do just that. During the raid, a fireball, supposedly intended only to light up the interior, was tossed through a kitchen window. When someone inside panicked and swept it into the fireplace, the device exploded, killing the James boys’ 8-year-old half-brother and blowing off their mother’s right forearm. Efforts to burn the house failed, and the detectives fled. On the night of April 12, Askew was gunned down in his backyard. Revenge may also have been the motive in July 1881 when conductor William Westfall was murdered by Jesse and his gang during a train robbery near Winston, Mo. Westfall may have been in charge of the train that carried the Pinkertons to Clay County the night of the fatal bombing.

Who were the robbers of Gads Hill? There is little doubt that the James brothers were among the culprits. Later, Jesse’s widow even admitted so. Jesse’s share of the loot, which she said was one-fifth of $2,000, financed their wedding and honeymoon trip to Sherman, Texas. And what outlaw other than Frank James would have been so original as to quote Shakespeare while robbing a train?

As for the Youngers, Cole insisted that he and his brother Bob were visiting a friend, William Dickerson, in Carroll Parish, La., at the time of the robbery. Dickerson and 10 of his friends verified the claim. Jim and John Younger, on the other hand, had no alibi, and it might be speculated that they were the two robbers described by widow Cook as looking like brothers. Another reason for suspecting Jim and John is that they showed up in St. Clair County at about the time the retreating outlaws passed through the area.

The fifth man stood over 6 feet tall and was 40 or more years old, a description that matched known gang member Arthur McCoy. While he and the other suspects were being hunted, a St. Louis newspaper printed an anonymous letter that claimed McCoy had recently died in Texas. His “death” had supposedly occurred just prior to the raids at Hot Springs and Gads Hill, making him innocent of those crimes. The mysterious letter may have been written by one of McCoy’s friends, or even by McCoy himself, in an effort to get the law off his back. At any rate, his demise at that time was never proved and, in the opinion of this writer, he remains a chief suspect.

Gads Hill, once described as “a small place, of no account,” later became, for a few years during the lumber boom, a thriving community of some 600 people. It had at one time three steam sawmills, a water-powered gristmill, a hotel, a blacksmith shop and even a railroad depot. Eventually, though, as the pine forest was decimated and the timber industry slacked off, people began moving away.

The face of Gads Hill has changed many times over the years. Houses and stores have come and gone; the railroad station is no longer there; and an old oak tree, where legend claims Jesse tied his horse, died years ago. As of this writing, the former settlement consists only of one house, a bar and grill and two “city limit” signs. A historical marker near the robbery site reads: “Gads Hill Train Robbery. Jesse James and Four Members of His Band Carried Out the First Missouri Train Robbery Here, January 31, 1874.”

The Gads Hill train raid was not as lucrative as some of the other James-Younger robberies. For example, the July 1876 train holdup near Otterville, Mo., netted the bandits more than $15,000. However, of all the crimes associated with these men, Gads Hill undoubtedly did the most to create the myth of Jesse James as an American Robin Hood. Reports of the outlaws stealing from the rich passengers aboard the train and tales of their giving to the poor widows and farmers as they escaped across the Ozarks are legendary. The chain of tragic events spawned by the crime, though, present a darker side to Jesse and his gang that even romanticists can’t ignore. These accounts of both good and evil, all byproducts of Gads Hill, aroused national interest in the outlaws when they were reported and remain to this day integral parts of the Jesse James story.

The Lost Loot of Gads Hill

In early September 1948, almost 75 years after the infamous Jesse James train raid at Gads Hill, Missouri, a man cutting timber near the robbery site stumbled onto a small cave-like opening in the side of a hill. He thought little of it at the time and after finishing his work returned home. A couple of weeks later, he mentioned the incident to a neighbor, who recalled a local legend. For decades, his friend said, it had been told that during their retreat from Gads Hill in 1874, Jesse and his gang had hidden all or part of the train loot somewhere in the Ozark hills of Wayne County. Perhaps this cave was the place.

Excited about the prospect of instant wealth, the woodcutter headed back to the woods. This time he brought along a flashlight instead of an ax. After crawling a few yards into the cave, he came upon a sizable room. There he discovered what was later reported to have been a large bundle of paper money, a “hatful” of old coins and a muzzleloading rifle. When he returned home and told the neighbor of his unusual find, rumor mills began to grind. The story spread, and big city news reporters, eager to get the story of Jesse James’ lost treasure, soon flocked to the scene.

A so-called reliable source claimed that the coins and currency taken from the cave amounted to more than $100,000 and that he had personally seen $10,000 in old gold coins in the woodcutter’s possession. A newspaper told of an armored vehicle parked in front of the man’s house, and adding even more interest to the unfolding drama was the reported arrival of two agents from the U.S. Treasury Department who had come to investigate the matter. All this created quite a stir, and the sleepy little village of Gads Hill, which had enjoyed so many years of peace and tranquility since the train robbery, found itself once again in the national spotlight.

The hubbub went on for several days; then, as quickly as the story had broken, it began to unravel. The woodcutter, it turned out, had not discovered Jesse James’ lost treasure after all, but only a crumbling book, a rusty old rifle with a rotten, worm-eaten stock and some 2-cent pieces (the oldest dated 1886, four years after Jesse’s death). He was surprised himself to learn he had found $100,000. “Only thing I ever told about,” he said, “was finding the gun and a few coins.” The poor fellow was apparently not to blame for the wild exaggeration. It was, as one newspaper put it, “merely the workings of normal backyard gossip.”

And so the story, like so many other debunked myths surrounding Jesse James, was laid to rest. On October 8, 1948, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat printed a final article that poked fun at the whole affair. Its headline appropriately read: “Jesse Fizzles Again.”

This article was written by Ronald H. Beights and originally appeared in the June 2005 issue of Wild West.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!