Facts, information and articles about John Mosby, a Civil War Commander during the American Civil War

John Mosby Facts

John Mosby Facts

Born

December 6, 1833, Powhatan County, Virginia

Died

May 30, 1916, Washington, D.C.

Nickname

The Gray Ghost

Rank

Colonel CSA

Battles Fought

Battle Of Bull Run

Peninsular Campaign

John Mosby Articles

Explore articles from the HistoryNet archives about John Mosby

» See all John Mosby Articles

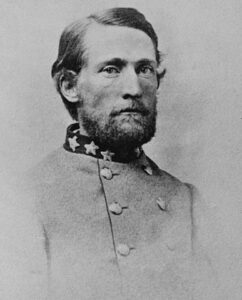

John Mosby summary: John S. Mosby was a Confederate cavalry commander. Known for his speed and elusiveness, he was given the nickname “Gray Ghost.” Mosby was born in Powhatan County, Virginia, on Dec. 6, 1833. As a child, he was a small boy with frail health and became a target for bullies in school, whom he always fought back against despite his ill health and smaller stature—though he admitted he always lost. While attending the University of Virginia, a confrontation with one such bully led 19-year-old Mosby to pull a pistol and shoot the bullying student—George Turpin, who had something of a bad reputation—nonfatally wounding him in the neck. He was sentenced to a year in jail, fined $500 and expelled from the university; however, Gov. Joseph Johnson pardoned him around Christmas of 1853. Mosby’s brush with the law had one positive outcome that would affect the rest of his life: he began reading law, tutored by the man who had been the prosecuting attorney in his trial, and opened his own practice in 1855. The following year, on December 30th, he married Pauline Clark, the daughter of a prominent Kentucky lawyer.

John Mosby In The Civil War

Although he had opposed secession, Mosby enlisted as a private in a company that was soon incorporated into the 1st Virginia Cavalry. In February 1862, he was promoted to first lieutenant and served as adjutant of the 1st Virginia, but he clashed with the regiment’s commander, William “Grumble” Jones. He resigned in April, becoming a staff courier and scout for J.E.B. “Jeb” Stuart. In Stuart, Mosby found a hero to emulate. Intelligence information Mosby provided aided Stuart’s famed “Ride Around McClellan” during the Peninsula Campaign of June 1862. In July 1862, Mosby was briefly a Union prisoner before being exchanged. During the course of the war he would be wounded seven times, and would lose an eye in a carriage accident in the 1890s; for someone who had been a sickly youth, he proved quite resilient.

In early 1863, he was authorized to recruit a group of partisans. Both Stuart and Robert E. Lee wanted the horsemen Mosby recruited to be under the command of the 1st Virginia Cavalry, but Mosby preferred operating outside the traditional military structure and argued that guerrilla actions would be useful in defense of Virginia and the Confederacy. He sought and received permission from Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon to organize a partisan unit; Company A, 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion, became part of the Provisional Army of Confederate States (PACS). Mosby was promoted to major, rising to full colonel before war’s end.

Since his men were not a traditional army unit, they could be called together to strike a selected target, then disperse afterward, making them hard to run to ground. This ability to strike quickly and then “disappear” gave rise to Mosby’s nickname, “Gray Ghost” (which was used as the title of a television series about him in 1957-58, starring Tod Andrews, and of a 1980s board game based on his exploits). Mosby himself, wearing a disguise, would often reconnoiter an area for a raid.

Mosby and his partisan rangers leaped to fame in a raid on the town of Fairfax Court House on March 9, 1863. With just 29 men, he captured Union brigadier general Edwin H. Stoughton, along with a number of horses. He also came close once to capturing a train on which General Ulysses S. Grant was a passenger. His primary area of operations in Northern Virginia became known as “Mosby’s Confederacy,” but he and his men raided as far north as Pennsylvania.

Mostly, Mosby’s Rangers (also called Mosby’s Raiders) disrupted supply lines, captured Union couriers, provided intelligence to the regular Confederate army, and generally became a thorn in the side of Federal officers operating in northern Virginia—so much so that some started executing guerrillas and Mosby retaliated by executing prisoners. He wrote to Gen. Phil Sheridan, commanding in the Shenandoah Valley, proposing that both sides end the executions, and Sheridan agreed. Mosby was still a wanted man, however. As a partisan, he was devoid of the protection under military law that he would have enjoyed as a member of the regular army.

Mosby after the Civil War

On April 21, 1865, twelve days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Mosby simply disbanded his rangers without formally surrendering. Because of his position outside the accepted military structure, he remained technically a wanted man until pardoned in 1866 by Ulysses S. Grant, with whom he became lifelong friends. He supported Grant’s election in the presidential campaigns of 1868 and 1872, which earned him the enmity of many Southerners, who did not realize he had urged grant to restore rights to former Confederates. Southerners were further angered by Mosby’s refusal to accept the Lost Cause version of history that attempted to separate slavery and the war. He wrote in an 1894 letter, “I always understood that we went to War on account of the thing we quarreled with the North about. I never heard of any other cause of quarrel than slavery.”

He was named U.S. Consul to Hong Kong, 1878–1885, and gave the federal government more headaches as he fought to reform corruption in the foreign service. He returned to practicing law, authored books, toured as a speaker, and held additional posts with the U.S. Government. He offered to raise a regiment during the Spanish-American War in 1894 but was turned down. He died in Washington, DC, on Memorial Day, May 30, 1916.

Articles Featuring John Mosby From HistoryNet Magazines

Featured Article

A Tour of “Mosby’s Confederacy”

A tour of ‘Mosby’s Confederacy’ gives a taste of the famed cavalryman’s hair-raising exploits.

“They had for us all the glamour of Robin Hood and his merry men, all the courage and bravery of the ancient crusaders, the unexpectedness of benevolent pirates and the stealth of Indians.” So wrote Sam Moore, a young man from Berryville, Virginia. Such extravagant admiration for Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his Partisan Rangers continues today, more than 130 years after the end of the Civil War.

Recently, a group of 35 Civil War buffs retraced Colonel Mosby’s exploits through Virginia’s Fauquier and Loudoun counties. The trip, sponsored by the Goose Creek Association, whose members come from both counties, was billed “The Ultimate Tour of the Gray Ghost’s Confederacy.” The tour began at the Mount Zion Baptist Church, three quarters of a mile east of Gilberts Corner, a place Mosby often used as a rendezvous point. Mount Zion Church is only a footnote in the annals of Civil War history, but a significant one to Mosby fans. Church property was never involved in the fight, which took place to the east of the two-story brick building. Because the church is an easily identifiable landmark, the skirmish that took place on July 6, 1864, between Mosby’s Rangers and Union soldiers was labeled the Mount Zion fight.

Tom Evans, one of the two guides, has conducted the tour more than 200 times. In the church cemetery Evans pointed out the graves of William “Major” Hibbs and James Sinclair, two of Mosby’s Rangers. Evans could not resist telling the group about Sinclair’s strange drinking habits.

Whenever Sinclair sat down to do some serious drinking, he would have a bagful of live snakes at his side. Between swigs of whiskey, he would bite off a piece of whichever reptile took his fancy. For obvious safety reasons, the head was eaten first. “It beats potato chips,” Evans quipped.

Sinclair’s penchant for snakes was not shared by his fellow rangers, but it illustrates the type of men who were attracted to the 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry–independent, bold men who, like Mosby, disliked the routine of ordinary military life.

“I preferred being on the outposts,” said Mosby, who found garrison duty boring. The 5-foot-7-inch, 128-pound Mosby was an ordinary-looking man who seemed an unlikely candidate for the dashing, romantic figure his admirers envision. Like Robert E. Lee, Mosby opposed secession, yet joined the Confederate forces when Virginia left the Union.

Mosby’s lack of enthusiasm for the military was evident from the beginning, and no one expected such an indifferent soldier to achieve military fame. Long after Mosby’s participation in the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, a member of his regiment commented, “There was nothing about him then to indicate what he was to be.”

Others disagreed. Brigadier General James Ewell Brown Stuart, Mosby’s mentor, saw a young man of intelligence and courage, and sent him on several scouting expeditions behind Union lines. Mosby’s intelligence reports on Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Union army may have been the reason Stuart allowed Mosby and nine men to remain in Loudoun County when he set up winter quarters near Fredericksburg.

Lee opposed partisan units, as did many old-line military officers. Too often men of questionable character with dubious motives filled the ranks of such units. When discipline broke down, the partisans often victimized the very citizens they had pledged to defend. Despite the military’s reservations, the Confederate Congress enacted a law in April 1862 that created partisan ranger units. Within a few months, partisan units ranging in size from regiments to companies were organized in eight states.

Almost 2,000 men would serve with Mosby over the next two years. Many were too young to join the regular army, yet Mosby favored these young troopers. “They haven’t sense enough to know danger when they see it, and will fight anything I tell them to,” he once noted.

“Mosby’s Confederacy” encompassed almost 125 square miles in the Piedmont region of Fauquier and Loudoun counties. The tour’s sponsor, the Goose Creek Association, focuses its efforts in the same area. The association promotes historic preservation, orderly growth and conservation of natural resources. Founded in 1970, the group has never lost a battle, according to President Janet Whitehouse–a record unmatched by Mosby. “The countryside is essentially what it was during the Civil War,” Whitehouse noted. “It’s a treasure.”

As the tour bus made its way down secluded country lanes, past open farmland and rolling pastures, it was obvious that the terrain favored guerrilla warfare. A lone sentry could sit astride his horse on a hilltop and see for miles. Forests provided natural cover, and the ubiquitous stone walls gave temporary refuge.

The people of Virginia may have been Mosby’s greatest asset. Jeffry D. Wert, author of Mosby’s Rangers, wrote, “When Mosby came to Virginia, he made his mission theirs and gave shape to people’s lives for over two years.” The rangers could not have operated without the cooperation and assistance of local citizens.

“Jeb” Stuart once cautioned Mosby to “not have any established headquarters anywhere but in the saddle.” Accordingly, Mosby and his rangers lived in “safe houses” throughout the region. Many had hiding places–trapdoors and secret wall panels that enabled them to go undetected when houses were searched by Union soldiers.

Hathaway House, the former home of James and Elizabeth Hathaway, was one of these places. Mosby’s wife, Pauline, and their children had joined him at the three-story brick house northeast of Salem (now Marshall) in March 1863. Their presence did not go unnoticed by an informant.

On the night of June 11, a detail of men from the 1st New York Cavalry was sent to Hathaway House to look for Mosby. Each room was searched, but all the soldiers found was a pair of spurs in Pauline’s bedroom. Rather than leave empty-handed, the New Yorkers arrested Hathaway and left with their prisoner.

Mosby had crawled out the bedroom window and hung from a limb of a large black walnut tree next to the house. Had any of the soldiers below bothered to look up, Mosby would have been discovered. The tree is still standing, but the limb is gone.

When the current owners, Jimmy and Sally Young, moved in, they doubted the story until tourists started showing up. In cars and by buses, people came to see the huge old walnut where Mosby had clung more than a century ago. Whatever doubts remained were put to rest when their daughter-in-law’s uncle, Virgil Carrington Jones, author of Ranger Mosby, confirmed the tale.

Throughout the tour, Evans pointed out a number of structures that had harbored wounded rangers or had been used as rendezvous sites. Stuart met with Mosby at Middleburg’s Red Fox Inn (then the Beveridge House) on several occasions, and a second-floor dining room is named in Stuart’s honor. Unlike the Red Fox Inn, many buildings remain in private hands and are not accessible to the public.

Over 80 percent of Mosby’s Rangers were Virginians, and that may explain the overwhelming support he received from local citizens. A Massachusetts cavalryman summarized the situation this way: “Every farmhouse in this section was a refuge for guerrillas, and every farmer was an ally of Mosby, and every farmer’s son was with him, or in the Confederate Army.”

Quarters were easier to secure than horses–the rangers’ lifeline. Most of the men had two horses, and Mosby reportedly kept six. To evade capture and effectively employ the element of surprise, the rangers moved constantly. Demolishing bridges, destroying railroad tracks and robbing trains took their toll on horseflesh.

Local farmers supplied some mounts, but most were taken from Union soldiers. When Mosby’s Rangers raided the Fairfax Court House on March 9, 1863, they captured 30 soldiers, two captains, Brig. Gen. Edwin Stoughton and 58 horses. Upon hearing the news, Abraham Lincoln remarked, “I can make brigadier generals but I can’t make horses.”

Mosby’s successes so irritated Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant that after the Berryville wagon train raid on August 19,1864, in which 29 of 30 Union soldiers were killed, the North’s top military leader told Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan to hang any rangers he captured without benefit of a trial. Sheridan’s main objective was to defeat Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, not Mosby, in the Shenandoah Valley, and he delayed committing any men to the new task.

Three weeks after Sheridan’s defeat of Early at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, Grant again instructed Sheridan to “clear out the country so that it will not support Mosby’s gang.” Brigadier General Wesley Merritt was given four days to destroy all barns and mills in Snickersville before moving on to other areas. A Middleburg resident reported, “The whole heavens are illuminated by the fires.” Mosby was a hunted man, his days clearly numbered.

Mosby’s military career nearly ended two months later at Lakeland, a two-story ashlar stone house near Rectortown. During the Civil War it was owned by Ludwell Lake, a huge man who never saw his shoes after the age of 20, according to local historian John Gott.

On the miserably cold, wet night of December 21, Mosby sought refuge at Lakeland because of the owner’s reputation for “setting a good table.” As Mosby was about to sit down to dinner, a Union soldier shot through a nearby window and wounded him in the abdomen.

When questioned by a Union officer, the grievously wounded Mosby said he was a lieutenant with the 6th Virginia Cavalry. The Yankees figured he would die of his wounds and left without him, but took his hat. By the time they realized whose hat they had, it was too late. Mosby had been taken by oxcart to another farm. He was continually moved from one safe house to another to avoid capture until he recovered.

The infamous house where Mosby was shot has attracted its share of tourists, much to the chagrin of the current occupant, who once looked up from the breakfast table and found a stranger staring through the window.

Other homes, such as Belle Grove, where diarist Amanda “Tee” Edmonds and her family lived, were frequented by Mosby’s Rangers. Two of Edmonds’ brothers rode with Mosby, and she faithfully recorded conversations with them and the other rangers who boarded at Belle Grove. The site was the perfect place for tour participants to have lunch on a brilliant fall day–or so they thought.

As lunch concluded, the sound of hoofbeats made some wonder if they had eaten their last meal. Suddenly the “Gray Ghost” and four of his rangers charged across the lawn in a shoot-’em-up style reminiscent of an old Western movie.

To everyone’s surprise, these modern-day rangers were from Lima, N.Y., a small town 30 miles south of Rochester. The role of Mosby was played by Donald Stumbo, whose two great-uncles were rangers. The 30-man unit Stumbo organized in 1967 participates in cavalry drills, ceremonies, parades and re-enactments. Each October, members travel to Virginia to ride the same trails Mosby’s Rangers rode in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Once the excitement died down and guns were holstered and horses tethered, Janet Whitehouse talked to the group about the Goose Creek Association’s success in protecting the local quality of life. “I feel very encouraged by our citizens who are increasingly aware of our countryside and the need to preserve it,” she remarked.

From Belle Grove the tour group proceeded to the Marshall National Bank, where, on the corner of Main and Frost streets, a small concrete marker identifies the 43rd Battalion’s disbanding site. Mosby had not known of Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865, until he read about it in the Baltimore American newspaper. Soon afterward, Union Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent a message to Confederate stragglers: “Those who do not surrender will be brought in as prisoners of war. The guerrilla chief Mosby will not be paroled.” Mosby chose to disband rather than surrender.

On Friday, April 21, 1865, almost 200 men gathered for a farewell address read by Mosby’s younger brother, William. In part, Mosby had written: “The vision we have cherished of a free and independent country, has vanished, and the country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our enemies.”

Mosby opened a law practice in Warrenton after the war and for nine years lived in the large white house at 173 Main Street. When he decided to support President Grant and the Republican Party, many of his men labeled him a political turncoat and accused him of deserting the South. People turned their backs on him when he walked down Main Street. One night someone shot at Mosby after he disembarked from a train at the depot.

Grant became so concerned for Mosby’s safety that he appointed him consul to Hong Kong. Other Republican presidents awarded him positions in the General Land Office and Department of Justice. It would be a long time before he returned to Warrenton.

Many years later, when a Baptist minister asked him if he knew what hell was, Mosby replied: “I certainly do. Anyone who has lived in Virginia and voted Republican knows what hell is.”

Mosby died on May 30, 1916, at the age of 82 and was buried in Warrenton Cemetery. His wife and several of their children lie beside him. Not far from the family plot is another daughter, Stuart Mosby Coleman, named after the man her father so admired–Jeb Stuart.

Sixty-six of Mosby’s Rangers are buried in the same cemetery. Perhaps these are the soldiers who forgave him; perhaps these are the ones who realized that after the war Mosby, like Grant and Lee, wanted to get on with rebuilding a divided nation and were willing to forgive their former enemies.

In an effort to stave off development in northern Virginia, a group of local preservationists has persuaded officials in Loudoun and Fauquier counties to designate a broad swath of land as the “John Singleton Mosby Heritage Area.” The proposed tract runs from the Bull Run Mountains to the Blue Ridge Mountains and is bounded by Virginia Route 7 on the north, and Interstate 66 on the south.

Leaders of the effort are planning to draft a map of the region indicating historic sites, as well as compiling educational resources for teachers and preparing a documentary film about the historic area, according to Whitehouse. The group also hopes to encourage tourism such as self-guided car tours through the region by re-erecting small road signs indicating historic locations in Mosby’s Confederacy.

Featured Article

John Singleton Mosby’s Revenge

A ragged line of Union soldiers stood in a field along Goose Creek in Rectortown, Virginia, on November 6, 1864. They jostled, chatted and joked with each other, pleased to be outdoors on a brisk autumn day. As prisoners of war these 27 Yankees had been confined to a brick store building in the village, waiting to be taken south to a Confederate prison camp. Little did they know that nearly a fourth of them were marked to settle a blood debt — minor characters in a major drama of reckoning between Lieutenant Colonel John Singleton Mosby and Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer.

A few minutes before noon their captors — members of the 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, better known to history as Mosby’s Rangers — led the Federals from the store to a gentle slope above the creek. It was likely Ranger Sgt. Maj. Guy Broadwater who addressed the prisoners. Seven Rangers had been executed by the prisoners’ Union comrades, Broadwater informed the group, and an equal number of them would share a similar fate. The words stunned and silenced the Northerners. A hat with 27 slips of paper, he explained, would be passed along the line, and each man must draw one slip. Seven of the pieces had been marked, and if a Yankee drew one of them, he was to be executed. A Ranger handed the hat to the first soldier.

Mosby, commander of the battalion, stayed in the village, unwilling to watch as his orders were carried out. Events during the past three months had forced Mosby to act. He did so reluctantly, or as he explained later: “I determined to demand and enforce every belligerent right to which the soldiers of a great military power were entitled by the laws of war. But I resolved to do it in the most humane manner, and in a calm, judicial spirit.”

Mosby had been conducting partisan operations since January 1863. An opponent of secession and a reluctant soldier, he had adapted to military life with surprising ease as a member of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Restless by nature, Mosby thrived on scouting and picket duty. In time he became one of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s most trusted scouts. On December 30, 1862, Stuart gave Mosby permission to conduct forays against enemy detachments, camps and wagon trains in northern Virginia during the winter months. Within weeks Mosby’s value as a partisan became evident. The climax came when he daringly captured Union Brig. Gen. Edwin Stoughton at Fairfax Court House on March 9, 1863.

The Stoughton capture brought Mosby fame both in the South and in the North. Young volunteers hurried to join the growing command. Mosby chose as a base the counties of Fauquier and Loudoun, where civilians enthusiastically sheltered, fed and concealed the Rangers. The local folks also alerted the partisans to the arrival of Federal units in the region, devising various warning signals. The area became known as “Mosby’s Confederacy,” and Mosby, an antebellum lawyer, served as its supreme military and civil authority.

The Rangers’ mission was, as he stated it, “to weaken the armies invading Virginia by harassing their rear.” Scouts constantly searched for targets. When one of them found an opportunity to strike, Mosby gathered his men at a prearranged rendezvous. With outriders ringing the column, the Rangers descended upon supply wagons, an enemy outpost, a railroad train or a body of Federal troops. The Confederates struck swiftly, with each man firing a brace of revolvers. “A small force moving with celerity and threatening many points on a line can neutralize a hundred times its own number,” asserted Mosby.

On June 10, 1863, at Rector’s Cross Roads (modern-day Atoka), Mosby organized his command into Company A, 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. He selected each officer personally while allowing the men to affirm his choices with a vote. Reserved and even taciturn, Mosby imposed his will and discipline upon youthful hotheads serving under him. If a member dared to cross him or behave badly with the civilians, Mosby banished him to the Confederate Army. He forged a matchless partisan command, earning official praise from Stuart and General Robert E. Lee for its exploits and timely gathering of critical intelligence.

By the summer of 1864, the battalion consisted of six companies, including an artillery company. Before autumn chilled into winter, Mosby organized two more companies. He counted between 300 and 400 officers and men in the command. Although he seldom used more than 100 to 150 Rangers on a raid, the reach of the partisans extended to the outskirts of Washington, D.C., and west beyond the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley. It was toward this latter region that Mosby increasingly shifted his operations as a decisive struggle for control of the “breadbasket of the Confederacy” unfolded that summer and fall.

A July raid into Maryland by a Confederate army under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early ignited the confrontation. After testing the defenses of the Federal capital, Early returned to Virginia, where he defeated a Union command in the Second Battle of Kernstown. He also sent cavalry units to burn Chambersburg, Pa., in retaliation for burnings and other depredations committed earlier that year by Federal forces in the Valley. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant reacted, with prodding from President Abraham Lincoln, by amassing an army at Harpers Ferry, and appointed Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan as its commander. On August 10, Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah marched south, up the Valley, against Early’s Army of the Valley.

During Early’s withdrawal from Maryland, Mosby had met with the general, expressing a “desire to co-operate with him.” Early probably accepted the offer and then ignored it. Mosby wrote later that the Confederate commander never sent him a message or an order. Early “never requested me to do anything,” said Mosby. Despite this, Mosby decided to augment Early’s operations by striking more frequently across the Blue Ridge against Sheridan’s supply and communication lines.

Within days of Sheridan’s initial advance south, Mosby and 350 Rangers, bolstered by a pair of howitzers, crossed into the Valley at Snicker’s Gap. On August 13, outside of Berryville, the Confederates attacked a supply train of the 1st Cavalry Division, routing its infantry guards and seizing more than 500 horses and mules, more than 200 head of cattle and about 200 prisoners. The action cost Mosby five casualties.

Farther south, meanwhile, Early’s army stopped Sheridan’s movement at Fisher’s Hill. With instructions not to suffer a battlefield defeat that might adversely affect Lincoln’s reelection campaign, Sheridan began retiring north. He had been ordered by Grant to destroy the fertile region’s crops, barns and mills and confiscate its livestock. As the Northerners retreated, cavalry units roamed the countryside, liberally applying the torch. A Union horseman admitted that it “was a sad sight,” as stunned residents watched their harvests and barns become engulfed in flames. “It was a phase of warfare we had not seen before,” he wrote, “and though we admitted its necessity, we could not but sympathize with the sufferers.”

Pillars of smoke marked the passage of Sheridan’s army. On August 19, Captain William Chapman and three companies of Rangers came upon 30 members of the 5th Michigan Cavalry who had burned the barn on the Benjamin Morgan farm southeast of Berryville, and were preparing to destroy the brick house. Enraged at the destruction, the Rangers charged, with Chapman shouting: “Wipe them from the face of the earth! No quarter! No quarter! Take no prisoners!” The Michiganders not killed in the attack were seized, shoved into the farm lane and shot. The Rangers rode away, seeking other enemy detachments.

One of the Federals, Private Samuel K. Davis of Company L, had feigned death when shot in the face. He crawled away and hid nearby. Two Rangers returned before long and examined the bodies to be certain they were dead. They found one trooper still alive and shot him in the head. When a contingent of Union cavalrymen arrived at the Morgan farm, Davis appeared and recounted what had occurred. The Civil War had long since lost its innocence, and now hard men on both sides seethed with anger — and plans for revenge.

Retribution for the Morgan affair came a month later at Front Royal. Approximately 120 Rangers under Captain Samuel Chapman, William’s brother, attacked a Union ambulance train as it rolled in from the south on the morning of September 23. Believing that the ambulances were traveling to Winchester without an escort, Chapmen divided his force, and one contingent charged toward the train. Chapman was mistaken, however, as the ambulances were trailed by two Federal cavalry divisions, led by Sheridan’s cavalry commander, Brevet Maj. Gen. Alfred T.A. Torbert.

The Rangers’ assault brought forward the Federal troopers. Suddenly, said an eyewitness, the Yankees “came up like a flock of birds when a stone is cast into it.” A Ranger claimed that the blue-jacketed horsemen “enveloped the devoted band like a cloud.” The Confederates scattered, racing toward shelter in the Blue Ridge. In the ensuing melee and pursuit, the Northerners captured five Rangers and 17-year-old Henry Rhodes, a resident of Front Royal who had borrowed a neighbor’s horse and joined Chapman’s men. Now young Rhodes and the Rangers were prisoners, surrounded by hundreds of furious Yankees.

The Federals’ anger had been fueled by a report that one of their comrades, Lieutenant Charles McMaster, had been shot after he surrendered at the Morgan farm. Squads of cavalrymen led away three Rangers — David L. Jones, Lucien Love and Thomas E. Anderson — and shot them. A Michigander, despite the pleas from Rhodes’ widowed mother, emptied his revolver into the youth. Torbert offered two remaining Confederates — William Thomas Overby and a Ranger named Carter — their lives if they revealed the location of Mosby’s headquarters. When neither man replied, Torbert ordered their execution. Earlier, Grant had advised Sheridan, “Where any of Mosby’s men are caught hang them without trial.” Members of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, McMaster’s regiment, carried out the order. On Overby’s body they placed a placard that read, “This will be the fate of Mosby and all his men.”

Mosby had been recovering from a wound when the executions occurred. When he returned to duty on September 29, he questioned Chapman and others about the incident, eager to know which Union officer had ordered the Rangers’ deaths. According to his men, residents of Front Royal had identified Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer as the guilty officer. Although the citizens had no way of knowing who actually gave the order, they recognized Custer. The Union general was a striking and conspicuous figure among the Federals, wearing a black velveteen uniform with golden braid, a red neckerchief and a broad-brimmed hat over his long blond hair. Mosby accepted the locals’ word as fact and blamed Custer. Until the end of his life, despite contrary evidence, Mosby adhered to his belief that it had been the Union’s “Boy General” who had callously executed his men.

“Reprisals in war can only be justified as a deterrent,” stated Mosby. He determined that when he had captured enough of Custer’s troopers, he would exact his own retribution for Front Royal. During the next several weeks as Ranger incursions into the Valley continued, his men separated members of Custer’s command from other prisoners. He informed Lee, “It is my purpose to hang an equal number of Custer’s men whenever I capture them.” Lee granted his approval and forwarded Mosby’s letter to Secretary of War James Seddon, who concurred. When Mosby received Lee’s authorization on November 4, he decided to act with a lottery.

The “painful scene,” as Mosby described the affair, began when a Ranger borrowed the hat of Lieutenant Charles E. Brewster, a commissary officer in Custer’s 3rd Cavalry Division. Placing the 27 slips of paper in the hat, the Confederate stepped in front of the first prisoner in line, held the hat above the soldier’s head and had him draw one slip. Slowly, the Ranger moved down the line from one Yankee to the next. A few of the captives prayed; one man cried. As the hat neared him, a young drummer boy sobbed: “O God, spare me! Precious Jesus, pity me!” When the boy drew a blank slip, he leaped into the air, exclaiming, “Damn it, ain’t I lucky.”

Six men and another drummer boy had chosen the pieces marked for death. The lottery had not sat well with most of the Rangers who had been given the duty, and now a young boy, James Daley, was among the condemned. Either Broadwater or another Ranger rode into Rectortown and informed Mosby of the results. “I didn’t know before there was a drummer boy in the lot,” Mosby recounted later. “I immediately ordered his release & lots again be drawn.” Nineteen prisoners repeated the nerve-wracking process, with one of them drawing the fateful slip of paper.

Five of the seven condemned Federals have been identified — Corporals James Bennett and Charles E. Marvin of the 2nd New York Cavalry, Private George H. Soule of the 5th Michigan Cavalry, Private Melchior H. Houghnickol (or Huffnagle) of the 153rd New York Infantry and Lieutenant Israel Clement Disosway of the 5th New York Heavy Artillery. Only Bennett, Marvin and Soule actually belonged to Custer’s command. The identities of the remaining two men remain uncertain.

Mosby assigned Lieutenant Edward F. Thompson and a detail of Rangers to escort the condemned prisoners to the Shenandoah Valley and carry out the executions as close to the Union lines as possible. The column started forth with a mounted Confederate in front of and behind each of the Federals, who walked. The Rangers bound the left wrist of each captive, attaching the rope to the pommels of their saddles. At Ashby’s Gap in the Blue Ridge, Thompson halted and allowed the condemned men to write a letter to family or friends.

Before they proceeded, Captain Richard Montjoy and Company D of the battalion met them, coming from the Valley with more prisoners. A fastidious dresser, Montjoy wore a Masonic pin on the lapel of his coat. Lieutenant Disosway, a fellow member of the order, signaled Montjoy with the Masonic distress sign. Montjoy convinced Thompson to swap Disosway for a Custer trooper whom he had captured. When Mosby learned of the trade, he angrily reminded Montjoy that the 43rd Battalion “was no Masonic lodge.”

Thompson’s detail descended the mountain and crossed the Shenandoah River at Berry’s Ferry. As the column passed Millwood, a cold rain began to fall, the heavy overcast deepening the night’s darkness. Near Berryville one of the Michiganders, George Soule, loosened his rope and slipped unseen into a ditch beside the road. When the Rangers and other prisoners disappeared into the blackness, Soule fled, eventually reaching the Union lines.

Thompson halted about 4 a.m. on November 7 in Beemer’s Woods, less than a mile north and west of Berryville. Mosby had instructed the lieutenant to shoot four of the prisoners and to hang three, just as the Yankees had done to the six Rangers and Henry Rhodes in Front Royal. The Confederates acted with slow deliberation, like men reluctant to perform the duty assigned to them. Mosby had ordered it, however, and they proceeded dutifully.

A Ranger grabbed Corporal Bennett and shot him in the left arm and head. Another Rebel walked up to Private Houghnickol, shooting the New York infantryman in the head and right arm. Corporal Marvin, Bennett’s comrade in the 2nd New York Cavalry, pleaded for time to say a final prayer. When he had finished, Thompson evidently stepped forward, placed his revolver to Marvin’s head and squeezed the trigger. The gun misfired, however. The New Yorker had loosened his hand from its bindings during the march, and he escaped through the woods after knocking Thompson down.

That left three condemned Federals. Their captors mounted them on horses, swung ropes over tree limbs, placed nooses around their necks and, as it had been done at Front Royal, whipped the horses. The identity of only one of the three hanged men is known — Wallace Prouty, who was identified by a small Bible with his name on it found in his pocket. Whether Prouty had drawn a marked slip or had been exchanged for Disosway remains uncertain. Before Thompson’s men departed, one of them hung a note on the body of one of the Federals: “These men have been hung in retaliation for an equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men hung by order of General Custer, at Front Royal. Measure for measure.”

Later that morning a Berryville resident who happened on the execution site examined Bennett and Houghnickol and found they were still alive. The Rangers had never checked to see if the two men had died. The citizen cut down the three corpses and buried them. He then placed the two wounded Federals in a wagon and hauled them into Winchester, where he delivered the note to Union Colonel Oliver Edwards. Bennett and Houghnickol survived. Bennett lost the use of his arm and much of his eyesight, while Houghnickol’s right arm had to be amputated.

When Mosby learned the details of the incident, the escape of Soule and Marvin did not bother him. “If my motive had been revenge,” he asserted later, “I would have ordered others to be executed in their place & I did not. I was really glad they got away as they carried the story to Sheridan’s army.” His object, he explained, “was to prevent the war from degenerating into a massacre….It was really an act of mercy.”

With this “act of mercy,” Mosby wanted the reprisals to end. He penned a letter to Sheridan, dated November 11, hoping that it would settle the issue. In it, he recounted the execution in Front Royal and an October 13 incident where Ranger Alfred Willis was hanged as a spy by Union Colonel William Powell. He added, “Since the murder of my men not less than 700 prisoners, including many officers of high rank captured from your army by this command, have been forwarded to Richmond, but the execution of my purpose of retaliation was deferred in order, as far as possible, to confine its operation to the men of Custer and Powell.”

Mosby then noted that seven Federals, “by my order,” had been executed. Although he probably knew by then that two Federals had escaped, it did not matter. His point was that he had issued the order for their executions.

He concluded the letter, “Hereafter any prisoners falling into my hands will be treated with the kindness due their condition, unless some new act of barbarity shall compel me, reluctantly to adopt a line of policy repugnant to humanity.”

Mosby asked Lieutenant Charles Grogan if he would deliver the letter to Sheridan, but Grogan refused to accept the dangerous mission. Lieutenant John Russell, a Berryville native and Mosby’s most valued Valley scout, agreed to the duty. Mosby assured Russell that if the enemy executed him, he would kill 100 Union prisoners currently in Ranger custody.

Carrying a flag of truce, Russell encountered Union videttes outside Millwood. The horsemen blindfolded Russell and led him to army headquarters at the Lloyd Logan home in Winchester. The Union general had withdrawn his army into the lower Valley after inflicting four battlefield defeats upon Early’s forces and destroying scores of barns and mills along the Federals’ retreat route. Valley residents had termed the days of destruction “The Burning.”

Russell delivered the letter to Sheridan, who read it. “Little Phil,” as he was called by his troops, conferred privately with Russell before writing a reply to Mosby. Neither Sheridan nor Mosby revealed the contents of this second letter. Whatever Sheridan responded, the executions and reprisals ended between the two foes.

The war, however, went on. Mosby’s Rangers continued to cross the Blue Ridge and clash with Sheridan’s units. On November 17, the Confederates routed and effectively destroyed Blazer’s Scouts, a command created by Sheridan and led by Captain Richard Blazer with the mission of wiping out the Rangers. Two weeks later Union cavalrymen entered Mosby’s Confederacy, carrying with them fire and smoke. But Mosby and his Rangers endured, finally disbanding on April 21, 1865, 12 days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Years after the war, Mosby recalled his decision to exact “measure for measure.” “It was not an act of revenge,” he argued, “but a judicial sentence to save not only the lives of my own men, but the lives of the enemy. It had that effect. I regret that fate thrust such a duty upon me; I do not regret that I faced and performed it.” And so he did, with a lottery of death outside the village of Rectortown on an invigorating Virginia autumn day.

This article was written by Jeffry D. Wert and originally published in the May 2007 issue of Civil War Times Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!