Standing on a mighty volcanic rock overlooking Scotland’s capital city, Edinburgh Castle is hard to miss. But that’s exactly what German bombing crews did when they took aim at the famous landmark during a zeppelin air raid over Edinburgh in 1916.

Most people associate German air raids against the British Isles with the Second World War. But German bombers started lurking above British skies more than 20 years earlier during World War I — sometimes in planes, but also in airships known as zeppelins.

Zeppelin Attacks on the UK

The German military under Kaiser Wilhelm II was particularly anxious to use airship technology to humiliate and inflict terror on Great Britain. The World War I bombing campaigns were no less brutal than those to follow in World War II, with many zeppelins dumping massive bomb loads in broad areas as they drifted across the sky. East London suffered particularly from these raids — one tragic example being a school at Poplar in which 18 children were killed, most of whom were 5-year-olds. An additional 37 children were wounded.

The month of April 1916 was particularly busy for the zeppelin raiders. In addition to Essex and Kent in England, the Germans also decided to target Scotland. As is evidenced by the bombast of German reports afterward, a raid against Edinburgh was intended not only to wreak material damage but also to be a propaganda coup.

Under cover of darkness, two zeppelins headed to Edinburgh, where they hoped not only to rain terror on the population but to land blows against the city’s prominent castle.

The mighty old Scottish fortress — as in medieval times — proved uncooperative.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The Mysteries of Edinburgh Castle

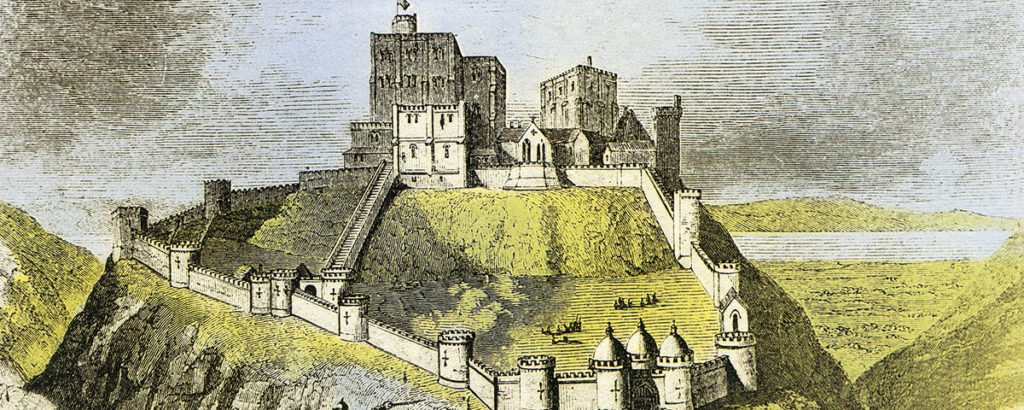

Edinburgh Castle, one of Europe’s oldest continuously fortified sites and the focal point of numerous wars, holds the distinction of being most besieged castle in Britain. Sited on the steep, craggy cliffs of a volcanic plug known as Castle Rock, it transformed into a stronghold bristling with towers and cannons throughout various fierce struggles over the centuries.

The castle, one of “preeminent symbols of the Scottish nation,” has a colorful history. It has not only proved difficult to assail with sheer military force but occasionally baffles people with its mysteries — the crown jewels of Scotland were lost inside it for over 100 years, and merely passing through the gates is said to bewilder university students into failing their final exams. A force of Jacobites who hoped to scale the ramparts in 1715 was left at a loss when its ladder turned out to be too short; the would-be besiegers were stranded and subsequently arrested.

The castle had a similarly mystifying effect on German invaders who drifted over it on the night of April 2, 1916. The German navy had improved its technology, allowing its airships to sneak up the coastline at night without being thwarted by cloudy Scottish weather.

“A new method to determine the location of the airship at night or in foggy weather had been introduced,” wrote Alfred Stenzel in a chronicle of German naval tactics in 1921. “Two radio message stations on land communicated the direction of the incoming radio messages from the airship. By taking a bearing on the magnetic lines, the point of intersection turned out to be the location of the airship, whose crew was now informed of it [their location] by one of the stations. The ‘directorial stations’ of the English were set up in a similar way with regard to naval radio messages.”

Castles: IMpregnable … and Pregnable

No Stone Unturned

Two German airships reached Edinburgh before midnight and flew over the city for about 40 minutes, dropping an estimated 24 bombs in less than an hour. Thirteen people were killed and 24 injured in Edinburgh and Leith. The Scots, however, had become aware of the enemy’s approach and blacked out all lights in the city, which may have prevented additional loss of life.

But whether it was the darkness, or perhaps some magic in the old stones of the fortress, that prevented the Germans from scoring even a single direct hit on the castle is an open question. Although one of the zeppelins “appeared to aim for Edinburgh Castle” and rained bombs over it, shattering windows on Castle Terrace, none of the missiles hit home.

A few bombs struck Castle Rock, but failed to touch the walls. Another bomb bounced up the road toward the main castle gate but failed to strike it. A bomb that struck a tenement in the shadow of the castle tore through the ceiling and four floors of the building — yet nobody inside was hurt. The bomb was recovered from the basement and became an heirloom of the MacLaren family.

The castle’s famous One O’Clock Gun, used to help ships keep the time, was allegedly fired during the raid in its first and only wartime action. Although it was firing blanks, the sound of the large gun firing may have spooked the zeppelin crews.

Conflicting Reports

“Scotland had its first experience with a Zeppelin raid …. No building of public importance was struck, but much damage was done in the residential quarter,” according to a report published in The Pantagraph of Bloomington, Illinois, on April 4, 1916.

Despite a propaganda-flavored German report to the Oberste Heeresleitung (Supreme Army Command) boasting of “very good results” from the April raids, including airship attacks on “dock facilities at the Firth of Forth” and “fierce and violent fires, massive explosions with extensive collapsing effects” overall, the raid had failed to strike military sites, including bridges and a nearby naval base.

Additionally, while the German report claimed that “all airships returned and landed undamaged,” two zeppelins were actually brought down by English gun crews during the April forays, with one shot down at the mouth of the Thames River.

An imperial Austro-Hungarian account of the raid into Scotland published in 1916 claimed that the German crews had dropped a total of 54 bombs, including 36 explosive bombs and 17 fire bombs. To date, the official number known in Scotland is 24 bombs. It has also been suggested that the number of total civilian casualties may have been higher than reported by British authorities at the time.

Incredibly Fortunate

However, the facts remain that the raid on Scotland was unsuccessful in its aims to sow widespread terror and mass destruction. Despite the tragic harm caused to civilians and residential areas, both Edinburgh and Leith were “incredibly fortunate in terms of civilian casualties and the number of buildings destroyed,” according to The Scotsman.

The raid also failed to strike militarily or culturally significant targets — including the castle. Like the Jacobites in 1715, the Germans were ultimately vexed by Edinburgh Castle and unable to conquer it.

Despite the advantages of airpower and modern explosives, the zeppelin bomber crew passed into history as just another one of a long line of invading powers that proved unable to bring the mighty Scottish stronghold to its knees.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.