Best known as a combat reporter trekking alongside battered American infantrymen, ace journalist Ernie Pyle got what he described as his “own introduction to modern war” during three months in Great Britain—witnessing the firebombing of London, accompanying an anti-aircraft gun crew shooting down German bombers, and mingling with civilians to document the heroic struggles of ordinary people in wartime.

“Britain’s civil army has its big blitz heroes who are the greatest this war has produced,” Pyle wrote for the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate. “But it also has its little heroes by the tens of thousands. I think it’s lots harder to be a little hero, because you have to keep so everlastingly at it.”

Starting in December 1940, Pyle traveled across England, Scotland and Wales, a self-motivated ambassador for Anglo-American alliance a year before the U.S. officially joined the conflict. He had volunteered to go, inspired by the brave stand of the British people against Nazi Germany and compelled by human interest. “From the day war was declared, I felt keenly for the side of Britain,” he wrote. “I simply wanted to go privately—just inside myself I wanted to go.”

Pyle first arrived in London, which he described during blackout as silent and “mysterious, darkly seen in a dream” filled with blurred shapes, shadows and tiny lights. Looking out of his hotel window upon the city, he claimed, “I can see no more than if I were standing in the middle of the Sahara Desert on the darkest night of the year, blindfolded and with my eyes shut.”

Taxi driving was “ramming forward into nothingness,” which at times resulted in fatal collisions with pedestrians. The East End seemed gloomy and haunted. “We walked amid wreckage and rubble and great buildings that stood, wounded and empty,” recounted Pyle. “It was ghostlike and fearsome in the wet dusk.”

Bombings and Fire

Witnessing the firebombing of London from a city balcony on Dec. 29, 1940, Pyle described the city as “ringed and stabbed with fire” in one of his most famous early war reports. Eager to “get out and see some shooting” at the enemy, the adventurous American soon found himself among an AA-gun crew—sipping tea. Bored with inaction, Pyle began to despair of missing a fight when the German bombers appeared. However, once the shooting started, he got more than he bargained for.

“Your first experience in a gun pit is a truly shocking one. From every side you seem to have been struck by a terrific blast of air that almost knocks you down … there are horrifying sheets of flame, as if everything on earth caught fire and exploded. And mingled with both of these things there is certainly the loudest noise you ever heard,” he wrote. “The whole thing shakes you, physically and spiritually.”

Always matter-of-fact, Pyle didn’t pretend to enjoy the experience. “I wished I was home in bed,” he wrote, adding ironically, “but then I swear I got used to it.”

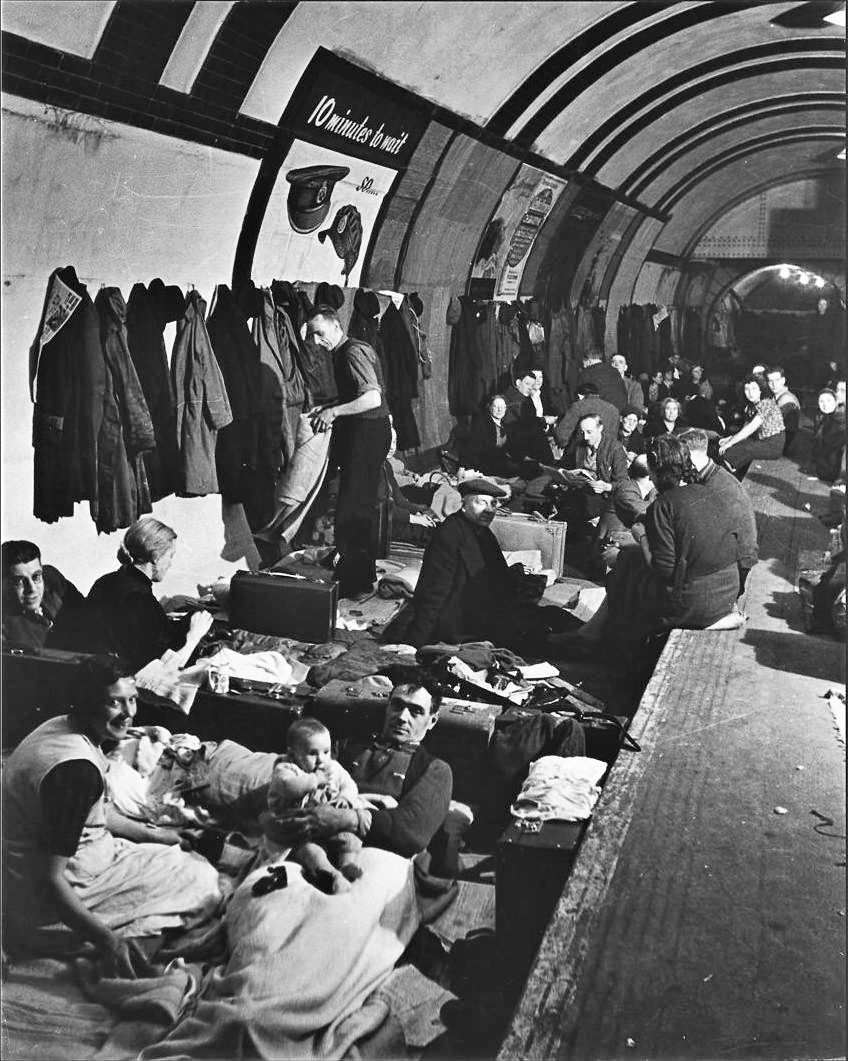

Yet despite being part of these literally earth-shattering events, Pyle claimed that what moved him most deeply was seeing British civilians huddled underground for protection. “It was not until I went down 70 feet into the bowels of the Liverpool Street tube and saw humanity sprawled there in childlike helplessness that my heart first jumped and my throat caught,” he wrote in February 1941, reflecting on his experiences. “People looked up as we came along in our good clothes and our obviously American hats. I had a terrible feeling of guilt as I walked through there … I couldn’t look people in the face.”

He described lethal enemy bombs as death “dealt by mystic lottery.” He witnessed the grief of a policeman unable to save a woman buried beneath rubble and saw handprints left on an outdoor wall of a man who had been crushed by a bomb.

Although surrounded by darkness, Pyle managed to focus his reporting on the goodness and bravery of ordinary people. “A lot of mighty fine sacrificing is being done in the bomb shelters of London. I don’t care where you go … there is somebody there who is giving his time and his strength and his heart for his fellow humans.”

British Spirit

Pyle seems to have been impressed by the solidarity of King George VI with his people. Writing of the bombing of Coventry, Pyle credited the monarch with bringing the shellshocked people “back to life again” with a surprise visit, saying that “somehow the realization that the King was there among them startled the people out of their stupor and they were actually able to cheer.” He also noted the ragged condition of Buckingham Palace, describing “three-fourths of the windows” as blasted out and covered with boards. “I’ll bet they wouldn’t fix it for ten thousand pounds,” wrote Pyle, “for it shows all England that their King is taking it too.”

Situations weren’t always gloomy. Pyle was cheered by British humor, getting lost in translation, and the tendency of people to keep upbeat despite hardships.

“Don’t tell me the British don’t have a sense of humor. I never get tired of walking around reading the signs put up by stores that have had their windows blown out. My favorite one is at a bookstore, the front of which has been blasted clear out. The store is still doing business, and its sign says, ‘More Open than Usual,’” Pyle wrote. “A sign on a bomb-scarred pub says, ‘Even Hitler Can’t Stop Us from Selling Watney’s Ale.’ And in front of a beauty shop along the Strand there is a sign saying, ‘Non-Stop Perming During Raids.’

Pyle also derived humor from the Home Guard long before it was lovingly satirized by the British TV show Dad’s Army. Pyle wrote that the “middle-aged Home Guardsmen” hated the Germans with a “frenzy” and were keen to catch any invading enemy parachutists who dropped into their path. “The Home Guardsmen say they intend to take no prisoners,” Pyle wrote, adding wryly, “I don’t know whether it has been definitely settled which is the stronger—steel or a man’s spirit. I only know that Britain’s Home Guard is armed with a state of mind that is likely to make parachuting a very unpleasant calling.”

The seasoned traveler also rejoiced in cultural differences—for example, the notorious British art of the understatement. “A single bombing is referred to … with traditional British reserve, as an ‘incident,’” he described dryly. “When you get there, the ‘incident’ will likely turn out to be half a block merely blown all to hell.”

People regaled him with stories of near escapes from bombs, which sometimes took the form of jokes and “tall tales.” Even bomb shelters were not all grim. Pyle’s self-described “favorite” shelter was at the Church of St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, where an enterprising pastor had converted medieval crypts into underground bungalows, complete with canteens for civilians and military personnel, and tables for billiards and ping pong. Sermons and solemnity were not part of the package, according to Pyle—but socializing, drinking and lighthearted merrymaking were definitely permitted.

“When you see a church with a bomb hole in its side and 500 fairly safe and happy people in its basement, and girls smoking cigarettes inside the sacred walls without anybody yelling at them, then I say that church has found a real religion,” Pyle wrote in admiration.

In light of what he saw, Pyle assured the American people that Britain would not fall before the terror of Nazi Germany—in Pyle’s view, the British spirit was unshakeable.

“The attitude of the people is not one of bravado… It isn’t flag-waving, or our own sometimes silly brand of patriotism,” according to Pyle. “It is simply a quaint old British idea that nobody is going to push them around with any lasting success.” Or, more simply put by Pyle: “The British won’t let anything interfere with their being British.”

A Lasting Impression

A born wanderer, Pyle soon felt the call to get back to his drifting. Yet he felt torn. “It is not easy to leave. There is something about leaving England in wartime that you cannot bear,” he wrote. Returning to his modest home in Albuquerque, N.M., which he shared with his wife, Geraldine, the roving writer enjoyed a respite amid the wide open spaces of the Southwest. Yet memories of the bombings and the people he left behind constantly nagged at him. “But when we sit in our west window at sundown it is past midnight in London, and the guns are going and the bombers are raising hell and my friends of yesterday are … alert to death and the sounds of death.”

Committing himself heart and soul to the war in Europe, Pyle later traveled side by side with the U.S. Army infantry—the military branch he liked best, he wrote, because he admired the “underdogs.” An unlikely star, Pyle would achieve fame for his writings on the triumphs, tragedies and endurance of the “little heroes” around him.

Reluctantly agreeing to report on the war in the Pacific, Pyle lost his life to a sniper’s bullet at Ie Shima in Okinawa, Japan, on April 18, 1945. He died alongside the people he loved most—ordinary men, striving and sacrificing, fighting and surviving amid extraordinary hardships and against all odds.

His early experiences in Britain had shaped his perspective on the war and had always remained with him.

“Day and night, always in your heart, you are still in London,” he wrote pensively after he returned home. “You have never really left. For when you have shared even a little in the mighty experience of a compassionless destruction, you have taken your partnership in something that is eternal. And amidst it or far away, it is never out of your mind.”