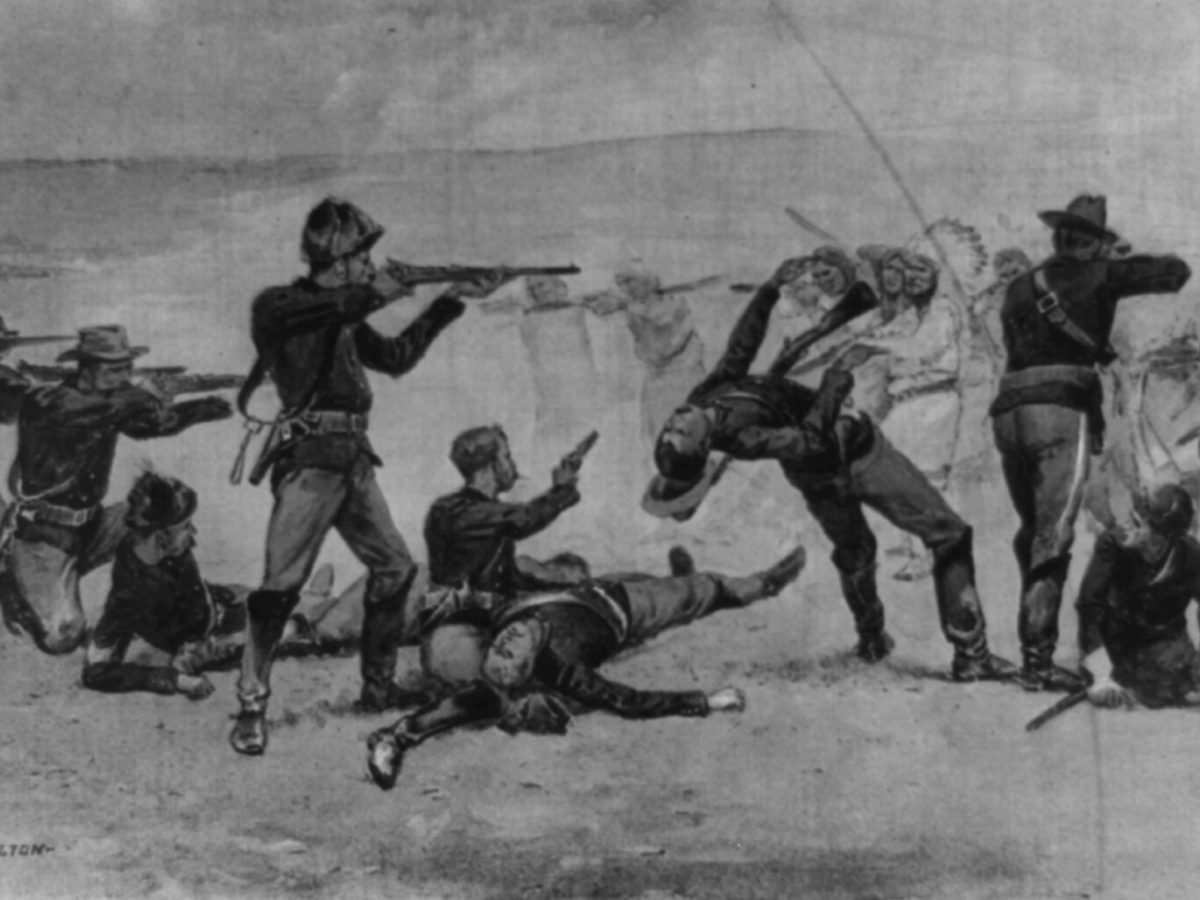

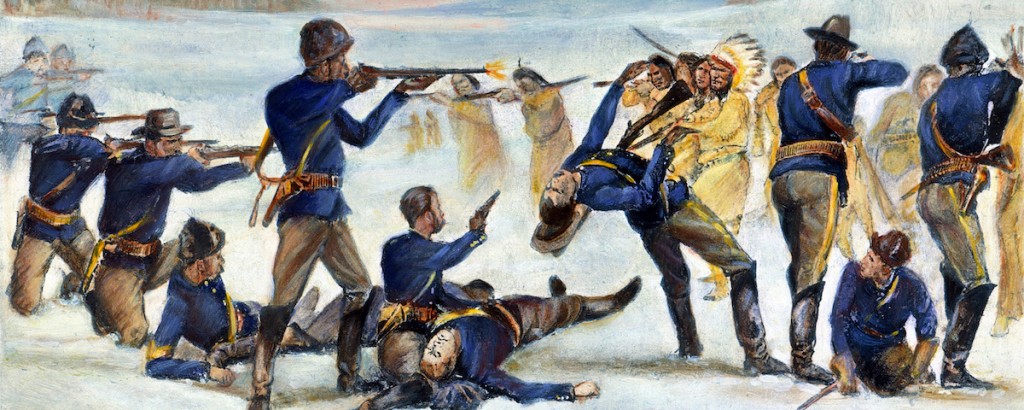

Dawn broke clear and cold on December 29, 1890. A winter storm loomed, but would not arrive until the next day. The night before, the U.S. 7th Cavalry had intercepted a band of Lakota Sioux under Minneconjou Chief Big Foot and brought them to a campsite beside a creek called Wounded Knee. The Indians had left their Cheyenne River camp and were en route to the Pine Ridge reservation. That night, the soldiers counted the Sioux, fed them and placed Big Foot, who was suffering from pneumonia, in a heated tent. In the morning, some troopers deployed along the ridges while others entered the camp, seeking to disarm the Sioux before escorting them back to the reservation.

The Lakota warriors, roughly 120 of them, were summoned to a “council circle” between their camp and the 7th Cavalry position some 200 yards north. Three companies of dismounted troopers moved in to surround the assembled braves, while two rows of mounted troopers waited in open skirmish order several hundred yards to the south and west. This was not a combat formation, but one more suited to crowd control, should the Sioux attempt to flee. As an added precaution, 7th Cavalry commander Colonel James W. Forsyth placed four Hotchkiss light artillery guns on a rise overlooking the camp.

Recommended for you

Through a translator, Forsyth demanded the Indians turn over all their weapons. Big Foot ordered his men to comply, but the warriors surrendered just two broken carbines. Forsyth, upset with this seeming betrayal of trust, ordered a complete search.

This order was the proximate trigger for the tragedy that followed.

Eyewitness accounts differ on what happened next. Most Lakota accounts describe a scuffle that began when one defiant warrior would not surrender his weapon. Typical of this version was the statement of Lakota warrior Turning Hawk, who testified to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., the following February:

There was a crazy man, a young man of very bad influence and in fact a nobody, among that bunch of Indians fired his gun, and of course the firing of a gun must have been the breaking of a military rule of some sort, because immediately the soldiers returned fire, and indiscriminate killing followed.

Others suggest the Lakotas had planned an ambush, cued to a prearranged signal by a holy man performing portions of the Ghost Dance. According to this version of events, as troopers searched the camp, the holy man danced and chanted amid the warriors, then bent to the earth and tossed a handful of dirt into the air. At this gesture, the Lakotas reportedly dropped their blankets and opened fire.

Consider the testimony of the 7th Cavalry translator, a mixed-race Sioux named Philip Wells:

Forsyth ordered [a trooper] to take the gun from the Indian, which he did. [Major Samuel] Whitside then said to me, “Tell the Indians it is necessary that they be searched one at a time.” The young warriors paid no attention to what I told them. I heard someone on my left exclaim, “Look out! Look out!” I saw five or six young warriors cast off their blankets and pull guns out from under them and brandish them in the air. One of the warriors shot into the soldiers, who were ordered to fire into the Indians.

Wells was not of the same tribe, so his account should be carefully weighed. But witnesses among Big Foot’s Minneconjou people provided similar testimony. Among them was Frog, an older warrior, who gave the following account just days after the hostilities:

I am a brother of Big Foot’s. We [the Minneconjou] left Cheyenne River, where we had been living, as Big Foot was tired of the bad treatment he had been getting at the hands of both the Indians and the white people—and besides we had been asked at different times during the summer by Red Cloud, Little Wound, Afraid-of-His-Horses and No Water to come to Pine Ridge agency and join them.

From the time we left till we came to Pine Ridge reservation, we had not been interfered with by the soldiers; they treated us with nothing but kindness and brought us into camp. The following morning the soldiers began blowing their bugles and began to stand around us in ranks, but I thought nothing of it, as it was their natural custom to do so. And then we [the men] were told to come out and sit down at a place near the door of Big Foot’s tent, which we did. Then a lot of soldiers got in between us and our camp, separating us from the women and children.

An officer then told us he wanted our guns, and as soon as we gave them up, he would give us provisions, and we could go on our way. We, the older men, consented willingly and began giving them up; we had all given them up, as I thought, when I saw an Indian with a gun under his blanket, and the soldiers saw it at the same time, and they took it away from him. They [the soldiers] commenced searching the Indians at the same time.

Meanwhile, the medicine man was going through the incantations of the Ghost Dance, stopped and began speaking to the younger Indians, but I paid no attention to what he said, as I had not the least fear of any trouble; so I pulled my blanket over my head and did not see anything until I heard much talking and loud voices. I uncovered my head, and I saw everyone had arisen on his feet, and I heard a shot coming from where the young Indians stood. Shortly after that I was shot down, and I laid there as I fell.

The firing was so fast and the dust and smoke so thick, I did not see much more of the fight until it was over. I heard someone saying: “Indians, all of you who are yet alive, raise your heads; the white man does not wish to kill you.” I raised my head and saw a man standing among the dead, and I asked him if he was the man they called Fox, and he said he was, and I said, “Will you come to me?” And he came to my side. I then asked him who was that man lying there half burned, and he said, “I understand it is the medicine man.” And I throw at him [the medicine man] my most bitter hatred and contempt. I then said to Fox, “He has caused the death of all our people.”

While Frog’s account does add to the mosaic, it too warrants some skepticism, as he spoke through a translator, and the language may reflect more what the translator chose to hear than what Frog actually said. Just the use of such words as “incantations” and “consented” seem out of place in the language of the time.

Captain Edwin S. Godfrey commanded Troop D, which was posted along the perimeter on the far side of camp from where the shooting started. In the wake of Wounded Knee, President Benjamin Harrison ordered an inquiry. Godfrey’s testimony, given 10 days after the event, suggests that at least some of the cavalry casualties came from friendly fire:

Q. State what part you took with your troops in the battle with Big Foot’s Indians on December 29, 1890?

A. I was posted on the side of the ravine, with the ravine between myself and the Indian village. I was under the command of Captain [Henry] Jackson, whose troop was there also and who was my senior. The troop was deployed with intervals, and mounted, about 50 yards behind the line of scouts.

Soon after the firing began, the cordon of sentinels and scouts rushed back to the line. I told the men to fall back slowly, which they were doing, until a number of Indians from the village came up across the ravine onto the plateau, and the shots from the other lines at these Indians were falling among the men….One of the shots from the Hotchkiss gun fell near the front of the line, when I ordered the men to rally behind the hill, which was just to our left and rear, where I dismounted to fight on foot. I here opened fire on the Indians who had crossed the ravine, who were attempting to escape. As soon as I forced them back or cleaned them out, I saw some going up the ravine. I cut off about 12 men and ordered Lieutenant [SRH] Tompkins to take them to a point that I designated, to cover that ravine and prevent their escape by that line.

Lakota warrior Dewey Beard picks up the narrative:

I saw men lying around, shot down. I went around them the best I could, got down in the ravine, then I fell down again. I was shot and wounded the first time.

I went up this ravine and could see that they were traveling in that direction. I saw women and children lying all over there. They got up to a cut bank up the ravine, and there I found a great many that were hiding.

We were going to try and go on through the ravine, but it was surrounded by soldiers, so we just had to stay in that cut bank. Right near there was a butte with a ridge on it. They placed a cannon on it pointing in our direction and fired on us right along. I saw one man shot by one of those cannons. That man’s name was Hawk Feather Shooter.

At this I followed up on to the prairie, for I thought I would die quickly now; but before reaching the top, an Indian pulled me back. As I fell, he was shot through the head. I took his cartridges, for they suited my carbine, and hobbled on till I met another woman coming towards me with a revolver in her hand. It was a soldier’s gun, which she had taken from a dead body, for she was very bloody. As she neared me, a white man peered over the bank and killed her. I fired, and he ran back.

Accounts from both sides concur that after the blowup inside the council circle and the breakout of the remaining warriors, the majority of the Lakotas sought refuge in the ravine. This shelter became a deathtrap, as soldiers trapped the fleeing Sioux in a crossfire. Again, testimony from both sides supports Beard’s contention that the Army wheeled at least one of the Hotchkiss guns to the lip of the ravine and fired directly into it. Finally, Beard notes that some of the women were armed and actively fighting back against the 7th Cavalry troops.

Jim Mesteth, another Lakota warrior, further described the resistance offered by the few remaining warriors in the ravine:

White Lance was the brave one. He had a gun, and they fought him all the rest of the day. He went up that canyon and got to the end of the canyon, but it’s bank all around there under there, so he got in there. He’d peep up and shoot down one of the soldiers. That fellow killed 12 soldiers there, and they never got him.

Of course, there are problems with this account too. If this one brave accounted for 12 of the 25 soldiers killed, that would leave just 13 killed by the other 120 braves, not to mention the soldiers’ own crossfire, which hardly seems likely.

Despite inconsistencies, however, such accounts offer a fairly clear picture of the Lakota side of the conflict. Thrown on the defensive after the first few minutes, their primary motive was to escape the killing zone. The Army’s version of events, although it largely matches Sioux testimony, takes an entirely different tack.

The 7th Cavalry’s main contention was that at least some Lakota warriors planned an ambush, blasting without warning into the ranks of troopers. Several officers further testified that it was crossfire from this phase that must have killed many of the women and children. This makes sense to some degree, but it alone doesn’t account for the dozens of Lakota deaths. Quite a number of those came later amid small groups in the ravine.

Captain Godfrey continues:

I was then ordered by Major Whitside to take the balance of my troop and make a pursuit of some Indians who seemed to be going up the hillside to the westward. After I got to the top of the divide, I saw only one Indian mounted, who made his escape up the ravine. I continued on to the westward of the creek, beyond the divide, to a high point from which I could see the country. I saw no Indians from that point. From there I scouted down the creek some distance. Some of my men called my attention that they saw some Indians in the creek bottom. I dismounted some men and sent them forward, enjoining them not to shoot if they were squaws and children, and called out, “How, kola,” which means friend. They, the Indians, made no reply, and the men, as soon as they got a glimpse of the Indians through the brush, fired about six shots. I heard the wailing of a child, and stopped the firing as quickly as possible. My men had killed one boy, about 10 or 17 years old, a squaw and two children.

A month after the massacre, Captain Frank Baldwin of the 5th Infantry found the bodies of a woman, two girls and a boy. An investigation ensued. On March 2, 1891, General Nelson Miles, commanding the Division of the Missouri at the time, reported the following:

Captain Baldwin’s report, which accompanied the papers pertaining to the Wounded Knee investigation, shows also that the tracks of a troop of cavalry horses were found near the bodies, as well as other evidence of the presence of soldiers. The boy, however, was not 16 or 17 years of age, but between 8 and 10, and the two girls between 5 and 7.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Captain Godfrey subsequently admitted that this party was killed by his men, but gave as an excuse for them that he did not think they could see the Indians on account of the brush. Persons who were on the ground and examined the brush declared that they were without leaves, and that persons could easily be identified in that locality at a distance of 50 yards.

The weight of this excuse, however, is entirely destroyed by the fact that the soldiers could see well enough to take deliberate and deadly aim and kill four persons with six shots, and so near were they as to burn the clothing and flesh of every victim, and one of their United States cartridge shells was found in the midst of the dead bodies.

To this day what happened after the initial outbreak of hostilities remains unclear. Certainly, in the weeks, months and years following the massacre, both sides had definite agendas and motives behind modifying their stories. Estimates of the Lakota death toll range from around 160 to nearly 300, a discrepancy further clouded by the delayed recovery of bodies. A burial detail didn’t arrive at the site until the first week of January 1891. The military detachment of this detail, led by Captain Folliot Whitney of the 8th Infantry, counted 62 men, 40 women and four children in its official report. Factoring in all official burial records, 157 Lakota dead appears the most accurate count, though it still doesn’t account for bodies taken away by the Sioux themselves in the days after the massacre. An estimate of somewhere between 200 and 225 seems more probable.

What matters in the end is that American soldiers, troopers of the 7th Cavalry and their officers, went too far on the morning of December 29, 1890. Fueled by fear, possibly enraged by perceived perfidy, they shot without discretion, killed without concern and left a lasting stain on the honor of the regiment. The only path to redemption lies in deeper introspection and understanding of what happened along that cold ravine 117 years ago.

For further reading, author Robert Bateman recommends Voices of Wounded Knee, by William S.E. Coleman, and Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866–1891, by Robert M. Utley

Originally published in the June 2007 issue of Military History.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.