On Jan. 3, 1891, a party of civilian burial contractors crossed the snowy South Dakota plains and arrived at the somber site along Wounded Knee Creek where five days earlier the last major confrontation between the U.S. Army and American Indians took place. Army burial crews had already tended to the dead soldiers, but Sioux bodies remained strewn across the ground. The hired civilians were to stack the frozen corpses in wagons for transportation to a waiting pit. The lingering press corps, a cadre of photographers and opportunistic artifact plunderers were on hand to witness the grim business.

The mass grave sat atop a rise that would become known as Cemetery Hill. During the December 29 clash the battery of Hotchkiss guns that had dealt death to so many of the Sioux had been positioned on the hill. The earth had already been heaped for entrenchment of the light mountain howitzers, so the burial detail had a head start in carrying out its assignment. Trundling their wagons to its lip, the crews unceremoniously dumped 146 bodies into the excavation.

As a somewhat gimpy lawman turned storekeeper, George Bartlett might have escaped recruitment for such distasteful duty, but he chose to be there nonetheless. At one point he folded his arms, resting them on the handle of his spade, and gazed at each distorted frozen face. He recognized many of the dead—some longtime friends, others familiar patrons of his nearby trading post. Watching the mass burial was painful enough. But five days earlier, from a distance, Bartlett had witnessed something even more troubling—the killing at Wounded Knee, a tragic event that has been termed both a battle and a massacre and at the very least was a largely one-sided brutal fight. By that time Bartlett had already lived an adventurous life, and more exploits lay in store.

Born in New Haven, Conn., on Aug. 25 1858, George Edward Bartlett moved with his parents to Sioux City, Iowa, in 1873. A year later the teenager struck out on his own, moving to the Yankton Agency in south-central Dakota Territory, where he worked at a reservation trading post. In 1876 he joined a prospecting party bound for the Black Hills. When the claims the men staked proved unsuccessful, they returned to Yankton. But in March 1877 young Bartlett ventured back into to the Black Hills with other aspiring miners. Though he again failed to hit pay dirt, he managed to land a stint as a rider with the mail delivery service between Rapid City and Fort Pierre, 170 miles to the east. Bartlett’s 60-mile round-trip route took him from Cheyenne River Station (near present-day Wasta) east to Deadmans Creek. He rode at night to avoid Indians. Caught out in a blizzard one night, he holed up in a hollowed-out cottonwood stump for three days with only a single jackrabbit for food. When the weather finally cleared, he recovered his horse and completed his route. It was during his time as a rider Bartlett first fractured his right knee, a recurring injury that would plague him for life.

He next turned to market hunting for deer, elk and bison. Working with a team of skinners, Bartlett used a .45–90 Sharps rifle to kill buffalo for their hides. He came to know the country and local Indians well, sometimes working as a scout and interpreter for the Army.

Some of the Sioux at the Pine Ridge Agency playfully referred to him in English as ‘Wounded Knee,’ after the creek that coursed 50 yards behind the store

Bartlett was still only 21 in 1879 when Deadwood-based U.S. Marshal John B. Raymond appointed him a deputy marshal. In that capacity the young lawman traveled all around the Black Hills and into the wilds of eastern Montana and Wyoming territories. His job sometimes required gunplay, most notably on a frigid Valentine’s Day 1884, his fifth year behind a badge.

Authorities had received word that local outlaw George Axelby and gang were planning to ambush a deputy then transporting cohort Jesse Pruden from Miles City, Montana Territory, to the Dakotas for trial. Bartlett joined a five-man posse to thwart their plans. The lawmen tracked the gang to the Stoneville Saloon, just over the Montana Territory line some 65 miles northwest of Deadwood. Bartlett and the others arrived late on February 13 in the midst of a snowstorm and spent the night bunked in Lew Stone’s ranch house, across a gully from the saloon. As the gang prepared to light out the next morning, the posse sprang the trap.

In the initial heavy exchange of fire, three deputies were wounded, one mortally. Creased in the skull by a bullet, outlaw Jack Campbell fell from his horse, gouging the saddle with his spurs as he fell. Axelby took a bullet to the thigh and had his horse shot out from under him, while a third outlaw was shot in the elbow and also lost his mount. As the rest of the gang dug spurs and galloped off, the wounded trio scurried into the underbrush and promptly vanished. The posse caught up to Campbell the next day. According to a wry newspaper report, in attempting to steal a horse, “He found one that was loaded, and it went off and riddled him with bullets.” Axelby was never heard from again.

In newspaper interviews a quarter-century later Bartlett claimed to have been shot in the kneecap during the Valentine’s Day fight—certainly a more romantic explanation for his lifelong limp. He also claimed to have received “sympathetic ministrations” from the legendary Calamity Jane.

Whatever the truth, though hindered by his injured knee, Bartlett continued to carry out his duties admirably and without complaint. Ever ambitious, he’d even taken on a second job, operating one of five Indian trading posts on the Pine Ridge Agency along the southern Dakota border. Barrett was fluent in several Sioux dialects and was comfortable among the Indians. He understood and respected their culture and listened to their troubles. The Sioux responded in kind and accepted, even admired, the storekeeper. They called him Huste, which means “lame” in Lakota, and painted a placard bearing his new name to hang over the store’s front door. Some playfully referred to him in English as “Wounded Knee,” after the creek that coursed 50 yards behind the store. For the next seven years Bartlett and the Sioux enjoyed a mostly harmonious relationship, with friendship at its foundation.

By 1890 there were no “wild” Indians in South Dakota. Subdued and restricted to reservations under federal administration, the Sioux adhered to the government regulations and boundaries, subsisted on government rations and shot the allotted government beeves in place of the nearly exterminated buffalo. But their level of compliance varied from settlement to settlement, and increasing numbers of disaffected Lakotas were placing their confidence in a quasi-religious movement known as the Ghost Dance.

As preached by its Paiute founder Wovoka, faithful practice of the dance would remove encroaching whites from the land, resurrect the Indians’ dead ancestors, restore the traditional ways of tribal life and restore the all-sustaining bison. Though Wovoka preached passive resistance, more bellicose followers spread word the ceremonial Ghost Dance shirts would deflect the bullets of the bluecoats. By November 1890 Black Hills settlers and Indian agents alike viewed the escalating movement as an incitement to war and called for the military to suppress the Ghost Dance, restore order and prevent an uprising. President Benjamin Harrison authorized troops on Nov. 13, 1890, and four days later Maj. Gen. Nelson A. Miles placed Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke in command of forces in the field at the Pine Ridge and Rosebud agencies.

Brooke, who established his headquarters at Pine Ridge on November 19, recognized the value of a knowledgeable, experienced man like Bartlett and without delay named him captain of the Indian Police. As he was tasked primarily with restricting white encroachment on agency lands, the Indians did not view him as a threat. Brooke also appealed to Bartlett to mediate a solution to the Ghost Dance problem before armed force became necessary. The lawman approached the Indians not as a badge wearer with a gun but as a friend who might reason with them. But there was only so much one man could do at a time of such mass discord on the reservations. By early December the number of Ghost Dance adherents at Pine Ridge had escalated alarmingly, their practice of its rituals becoming increasingly frenzied. By Christmas things had come to a head.

As December 29 dawned, Barrett stared out of the window of his store on Wounded Knee Creek. The rising sun gradually illuminated the cluster of Sioux tepees to the southwest. Also visible were the bivouacking soldiers who’d cordoned off Chief Big Foot’s village on three sides. These were troopers of the grudge-holding 7th U.S. Cavalry, Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s old command. Several of the officers and enlisted men present had ridden with him to the Little Bighorn in June 1876. Commanded by Colonel James W. Forsyth, the force comprised eight companies of 800 men. The Hotchkiss battery was dug in atop the hill 300 yards to the northwest. Its four rapid-fire guns, already ranged in and directed at likely escape points, stood ready to sling their 1.65-inch explosive projectiles. The night before many men of the 7th had reportedly been drinking.

Bartlett never revealed what his thoughts were at the time, but he must have suspected things would not end well for the Indians

Bartlett never revealed what his thoughts were at the time, but he must have suspected things would not end well for the Indians. At some point he left the store window, mounted a horse and rode to a hilltop three-quarters of a mile distant, presumably for a better view.

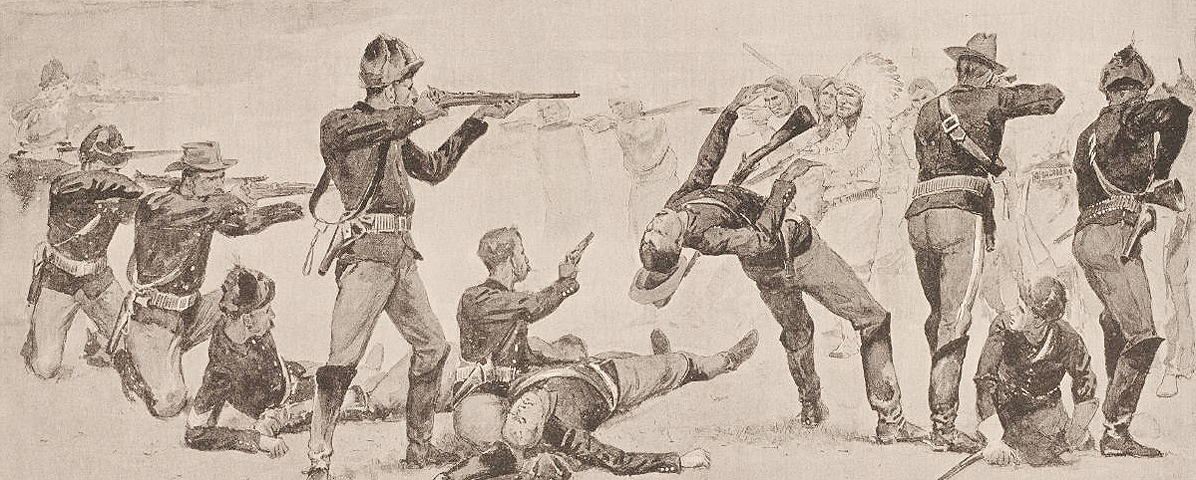

Forsyth had demanded the Sioux surrender their weapons, but a search of the Indian village turned up only a scattering of archaic guns. The critical moment came when the increasingly frustrated colonel ordered soldiers to bodily search the gathered warriors and confiscate any remaining weapons. By some accounts medicine man Yellow Bird then tossed a handful of dirt in the air to signal the Indians to open fire. Bartlett upheld another eyewitness who said an Indian rifle discharged accidentally as a soldier wrested it from its protesting owner’s hands. At least four Sioux warriors have been identified as the “trigger man.” Barrett didn’t mention a name, only that “a single shot was fired,” answered in turn by a fusillade from the troopers and the subsequent muddled and deadly fight. When the dust and smoke settled, 25 soldiers lay dead and 39 wounded, six mortally—many thought to be victims of friendly fire. Upward of 200 Indians were killed and wounded, including women and children. Though the soldiers’ actions would be condemned in some circles, 20 would receive the Medal of Honor.

It was Captain Bartlett who dashed overland to Pine Ridge to deliver the distressing news to General Brooke. “Impossible! Impossible!” Brooke exclaimed in disbelief. Bartlett also informed agency physician Dr. Charles Eastman, who was of Santee Sioux, English and French ancestry. The doctor rushed to help the wounded. “Wholesale murder” is how he described the horrific scene. “Dead Injuns laid [sic] around pretty thick. The worst of it was so many women and kids killed.”

On December 30, the day after the deadly confrontation, Bartlett told a reporter from Great Falls, Montana Territory, about two wounded boys found miles from the village—one shot through both eyes, the other through a hip. Both died within days. Presumably tormented by such dreadful images, Bartlett said nothing more publicly about what he’d witnessed until Nov. 30, 1903. That’s when he spoke with Eli S. Ricker, a Nebraska journalist who recorded many firsthand accounts from the Indian wars on ruled tablets (“Ricker Tablets”), published posthumously under the title Voices of the American West. By the time of their interview, Bartlett’s memories had faded, or he’d repressed them. “I can’t remember all those things,” he admitted to Ricker. “There was so much happened about that time.” When pressed about the Indians’ attempts to escape, Bartlett spoke in broad terms: “Oh, they run in every direction, and the soldiers followed them and killed them while they run, and some of them sat down on the ground and did not try to do anything.” He did allow himself to recall five fleeing women being overtaken by two soldiers. Resigned to their fate, the squaws sat down, covered their faces with their shawls and were summarily executed. “You saw that?” Ricker asked. “Yes,” came the clipped answer.

From his hilltop vantage Bartlett also witnessed firsthand the destructive power of the Hotchkiss guns. When the firing broke out, one warrior had hidden in a soldier’s Sibley tent. Unwisely showing himself at its open flap, he received a direct hit to the torso. “There were chunks taken out of his body,” Bartlett recalled, “as though they were pulled out.” A wagonload of Sioux women was rolling toward the refuge of the captain’s store when struck by another Hotchkiss projectile that “burned the wagon half up.” All were killed, Bartlett told Ricker.

On New Year’s Day 1891 Bartlett joined a party of civilians on the field to collect bodies and search for survivors. Around midday as the men approached a blanket-shrouded tangle of seven dead Indian women, the captain thought he heard the whimper of an infant. He instructed the others to keep silent. On hearing another cry, the men pried apart several of the frozen corpses and discovered an unharmed months-old baby girl wrapped in a shawl. Bartlett turned her over to a Sioux couple he knew. At some point after her rescue the girl was given the wistful name Zintkala Nuni, Lakota for Lost Bird. On January 19 Nebraska National Guard Brig. Gen. Leonard Colby and wife Clara adopted the child in what some viewed as a public relation’s move, even as a stepping stone to political office. That June, coincidentally or not, President Harrison appointed Colby assistant attorney general of the United States. Over the following decades Bartlett kept in touch with Lost Bird, who died during an influenza outbreak on Valentine’s Day 1920.

In the aftermath of the Wounded Knee tragedy, 1st Infantry Captain William Dougherty was appointed acting agent for Pine Ridge, charged with “removing intruders from the reservation.” Among his first orders of business was to send Bartlett a rather terse dispatch: “Your presence at this agency being deemed detrimental to the interests of the Indians and of the government, you are hereby notified and required to depart from the Indian reservation forthwith.” Exactly why Dougherty did this is uncertain, but Bartlett immediately resigned his deputy marshal’s commission of a dozen years. Some years earlier he’d started a horse ranch just across the Nebraska line as a side venture, and he is thought to have retired to it. Not for long.

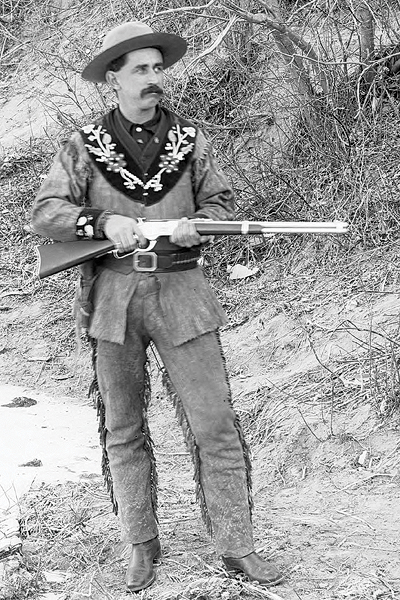

The entertainment business beckoned in 1893, a promoter hiring Bartlett to shepherd a band of Pine Ridge Indians to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. While there he and his wards signed on with a minor traveling Wild West show, the captain himself putting on a shooting exhibition. Other opportunities followed. On the road with Adam Forepaugh’s Circus in 1896, Bartlett added a Deadwood stagecoach to his performance and became a popular attraction. Newspaper reporters, intrigued by his shooting skills and real-life adventures with a gun in the Old West, often grilled him to satisfy their Eastern audience’s appetite for hair-raising, bloody adventures. For the most part Bartlett obliged their requests for rehashes of the shootout at the Stoneville Saloon and the occasional question about his memories of Wounded Knee.

In 1897 he hit the road with a traveling theatrical troupe, appearing that January in the melodrama “The Great Train Robbery” at Heuck’s Opera House in Cincinnati, Ohio. Between performances he took questions from The Cincinnati Times-Star. The reporter in particular sought validation of accounts that women and children were killed at Wounded Knee. Speaking hesitantly, Bartlett confirmed that in the ferment of the initial fight soldiers regarded all Indians as hostile and shot them indiscriminately. The troopers then chased down fleeing survivors. In the wake of the killings, he added, many soldiers were heard to remark that accounts with the Sioux for the Custer massacre had been “partly squared.” Bartlett later sat down with a writer from The West Coast magazine, who paraphrased him as saying, “The ‘battle’ was a deliberately planned, ferocious slaughter of Sioux men, women and children.”

When Bartlett made a 1898 stop in his hometown of New Haven, Conn., a Marlin Firearms Co. executive offered him a position as its traveling representative. He accepted and was soon wooing crowds at trap shoots up and down the East Coast. In 1899 he broke off his arrangement with Marlin to tour with Pauline Cooke and May Clinton, traveling sharpshooters who billed themselves as Misses Cooke and Clinton. Bartlett and the Misses were a hit and planned to tour Europe, opening in Copenhagen in April 1901. When that trip fell through, George and May made other plans and got married. That spring the Peters Cartridge Co. of Cincinnati persuaded Bartlett to represent their firm in the same fancy shooting capacity he’d enjoyed with Marlin. By then he was a polished showman with a national following. Exhibition shooters customarily crowned themselves with the honorific of “Captain.” In following tradition, Bartlett took on a dual captaincy of sorts.

For a decade the captain toured the country for Peters, plinking nuts, coins, rocks, washers and other thrown objects out of the air with a rimfire rifle. His trademark stunt, reducing a thrown brick to dust with a high-powered Remington rifle, was always a crowd-pleaser. His routine was among the first captured by motion pictures.

On Aug. 19, 1911, after an unspecified illness, 52-year-old Bartlett died at his home in Los Angles. He left behind a notable collection of Indian artifacts, as well as the Colt six-shooter, gun belt, knife and scabbard he’d “inherited” from Jack Campbell after the Stoneville shootout. (Years earlier Bartlett had sold Campbell’s saddle, which still bore the marks from the unfortunate outlaw’s spurs.) Author E.A. Brininstool recalled that shortly before Bartlett’s death, his old friend gave him the “old gun belt, knife, knife scabbard and pistol holster.” The Colt had vanished into memory, much like the outlaw and the man who brought him to justice. WW

Jim Foral writes from Lincoln, Neb. For further reading he suggests Voices of the American West: The Settler and Soldier Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, edited by Richard E. Jensen; Trail to Wounded Knee: The Last Stand of the Plains Indian, 1860–1890, by Herman J. Viola; Voices of Wounded Knee, by William S.E. Coleman; American Carnage: Wounded Knee, 1890, by Jerome A. Greene; and Eyewitness at Wounded Knee, by Richard E. Jensen, R. Eli Paul and John E. Carter.