Marvin Strombo stood next to the mailbox of his Montana home and opened the envelope. He froze, staring at the photograph in his hand. In the photo was a gravestone marked with the name of old friend, alongside dates: Martin Russell Dyer Jr., June 14, 1923 – June 30, 1944.

More than seven decades had passed since he’d met Dyer, when the two Marines bunked next to each other on a troopship destined for the battle of Saipan. But here his image was, bringing back old memories as Strombo sorted through the accompanying letter from an author who’d previously interviewed him about his experiences.

Back in the Second World War, Strombo, who was trained as a scout sniper, had just seen combat on Tarawa before heading toward Saipan. Dyer had already fought — and barely survived — Guadalcanal, intense fighting nearly two years earlier that set the stage for Marines and soldiers to battle their way through the Pacific en route to mainland Japan.

Strombo, who shared his stories with the inquiring author Joseph Tachovsky, would eventually do the same with graphic novelist and Air Force veteran August Uhl, who pieced them, and numerous other tales, together in the recently published third volume of “Full Mag: Veterans Stories Illustrated.”

Talking to Uhl, Strombo noted that Dyer gave no false bravado during their discussions about what was to come.

“He would talk about fear, how some could cope with it and others had a hard time,” Strombo recounted. “It was an emotion that was hard to control.”

Shortly before they landed on the beaches of Saipan, Dyer shared his own secret with Strombo. He hadn’t handled combat on Guadalcanal as he’d hoped. He couldn’t cope.

“Then he told me the reason he volunteered for the scout snipers was to see if he could live up to being able to cope with it better than he did at Guadalcanal,” Strombo said.

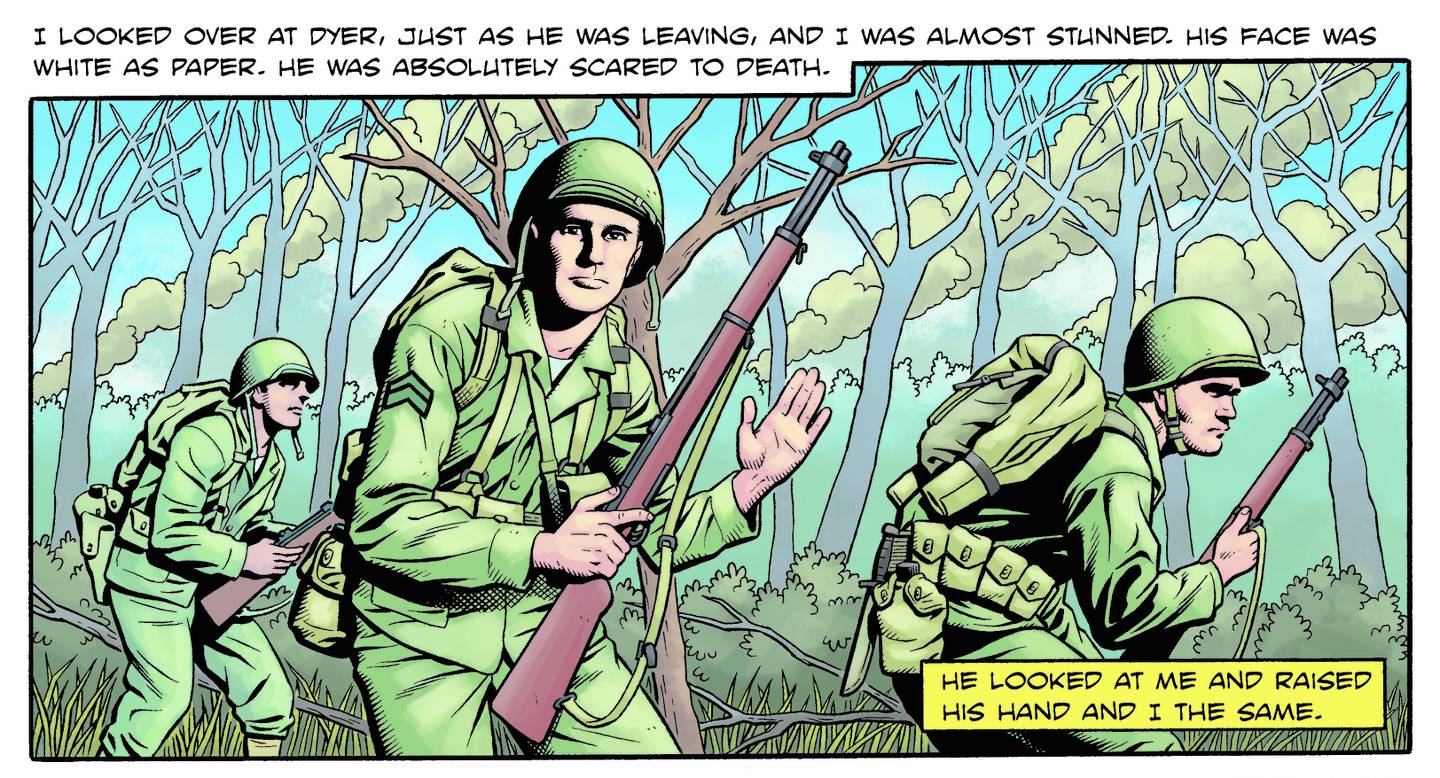

Moving inland on Saipan, Dyer’s lieutenant told him to take his squad and inspect a ravine on their left flank.

“I looked over at Dyer, just as he was leaving, and I was almost stunned,” Strombo said. “His face was white as paper. He was absolutely scared to death.”

Yet Strombo would later learn that his good friend displayed anything but fear on that patrol. In his Navy Cross citation, officials recounted how, after two failed attempts to knock out a machine gun nest, Dyer told his squad mates to keep eyes on the tree line just before he ran into the open, exposing himself to draw enemy fire so his Marines could pinpoint the target.

Though wounded, Dyer then led a third assault on the position before succumbing to his injuries.

Strombo, meanwhile, would fight through his time on Saipan and on other fronts until the end of the war. He would then return to civilian life, only to be called back to fight in Korea. In a shut closet at home he kept a captured Japanese flag and other souvenirs, but the memories didn’t stay closed up with them.

Strombo returned to Montana but left numerous times for work, even finding a wife from El Salvador while building roads in Central America. He’d often bring her back to snowy Montana, where they would have three children that he raised alone when she left to return home.

“He never remarried, he just focused on us,” his daughter, Sandra Williamson, said.

As the years elapsed, Strombo worked and cared for his family. Williamson said he never really talked about his wartime experiences, but she remembers him comforting friends and relatives whose sons were fighting in Vietnam.

Her father did share details of the Marines’ unorthodox work on Saipan, however, with the son of his late platoon commander, Lt. Frank Tachovsky. After interviewing surviving members like Strombo, the platoon commander’s son, the aforementioned Joseph Tachovsky, penned the book “40 Thieves on Saipan,” recounting the unit’s exploits.

The Marines of Strombo’s unit were also called “Tachovsky’s Terrors” in a December 1944 issue of Leatherneck Magazine, but it was the Marines in the 6th Regiment who gave them the name “The 40 Thieves,” a moniker earned due to the snipers’ preference for sneakers over boots, which allowed them to slip quietly through the jungle.

For the new “Full Mag” stories, Strombo shared more intimate experiences, including a terrible war-induced nightmare that plagued him throughout his life and the close calls he had in both World War II and Korea, during which times he said he heard a mysterious voice amid the carnage.

“As I was laying in a prone position, someone or something whispered, ‘move back,’” he said. “I immediately moved back. Just as I moved a bullet hit the sand where I had moved from.”

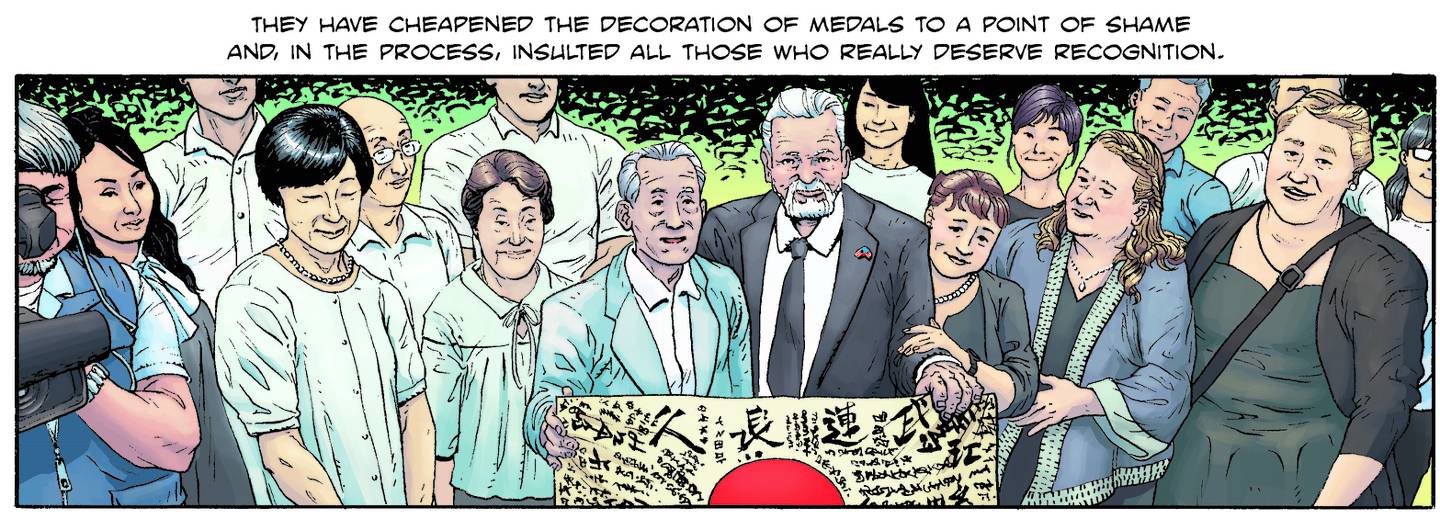

The illustrations also depict a world of reconciliation, such as when Strombo returned the Japanese flag he’d retrieved from a fallen enemy to the soldier’s family in Japan.

Those stories capture the essence of what “Full Mag” creator August Uhl seeks to share in each of the volumes, which, after interviews, research and artwork, take about 13 to 15 months start-to-finish, he said.

And they feature stories from World War II to present day.

Early projects included interviews with a list of subjects such as David Thatcher, at the time the last of two survivors of the Doolittle Raid. A local story detailing Uhl’s interview with Thatcher, who died in 2016, just happened to catch the eye of Williamson, who called Uhl to see if he’d like to hear her the story of her father, a fellow Montanan.

Strombo agreed, and this time, allowed his daughter to see his notebook that was filled with stories he’d written during his later years, stories that he couldn’t leave behind.

Strombo later read Uhl’s draft and offered his notes. Williamson remembers her 96-year-old father looking over and chuckling.

“Well, I guess I’m famous now,” he said.

Marvin Strombo died at his Missoula home surrounded by family on June 23, 2020.

Up next for Uhl is a historical graphic magazine that’s tentatively titled “Saved Rounds,” featuring both nonfiction and fiction veteran stories. It’s likely to be published next year at the earliest.