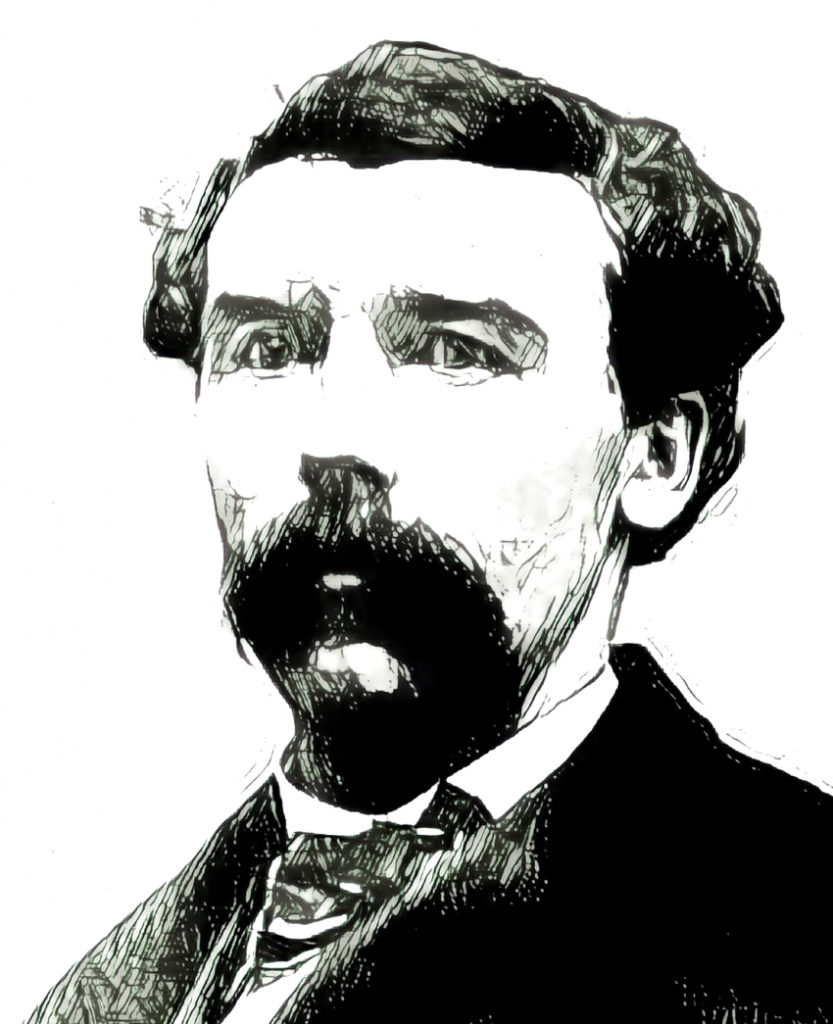

This letter was written by William Graham of Co. B, 107th New York Infantry.

William enlisted at Elmira, New York, on July 18, 1862 as a private. He was promoted to a corporal on Nov. 1 1862, and mustered out of the regiment at Washington, D.C. on June 5, 1865 as a first sergeant (according to his obituary).

William emigrated from County Down, Ireland, with his parents in 1850. They arrived in New York City aboard the vessel Roscius on Sept. 18, 1850. The ship’s passenger manifest tells us that his parents were James Graham — a 64 year-old farmer, and Jane Shaw, 48. At the time of his enlistment, William resided in Wayne, Steuben County, New York.

After the war, the Rathbone-West Union (Steuben county) town clerk recorded William’s military experience in the 107th New York as follows: “Was in the Battle of Antietam. Joined Sherman at Chattanooga and participated in nearly all the engagements his regiment had until Johnston’s surrender in North Carolina. Discharged June 5th 1865. P. O. Address, Weston, N.Y.”

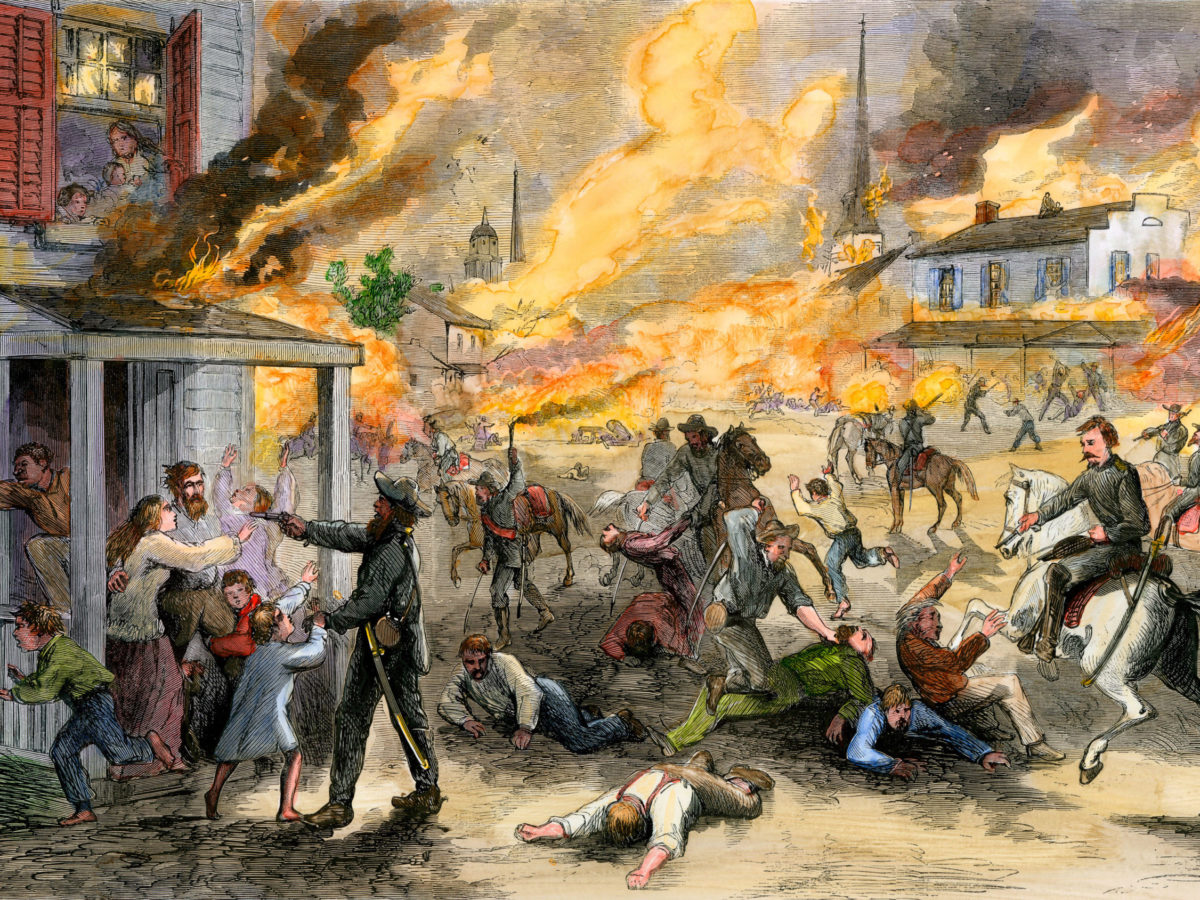

Maelstrom of War

In his letter, William describes the maelstrom the 107th New York found itself in on the morning of Sept. 17, 1862 near Miller’s Cornfield and the East Woods on the Antietam Battlefield.

After making their advance, the yet untested regiment soon found itself hunkered down behind a fence on the Smoketown Road near Mumma’s Lane. Across the clearing before them, through the dense smoke of battle, they could just barely make out the Dunker Church and the West Woods beyond. On the right before them was Monroe’s Battery and to the left was Owen’s Battery, both under heavy fire from Rebel cannoneers. And when their right flank was threatened, the regiment was ordered to change front to meet the new attack, only to find themselves soon afterward prostrate again between two rows of Union artillery, every cannon belching out fire and canister as fast as it could be loaded. For four hours, the regiment lay pinned to the ground between the rows of artillery, one member of the regiment [Newton T. Colby] telling his father he “tried to get as thin as possible and felt somewhat like a pancake.”

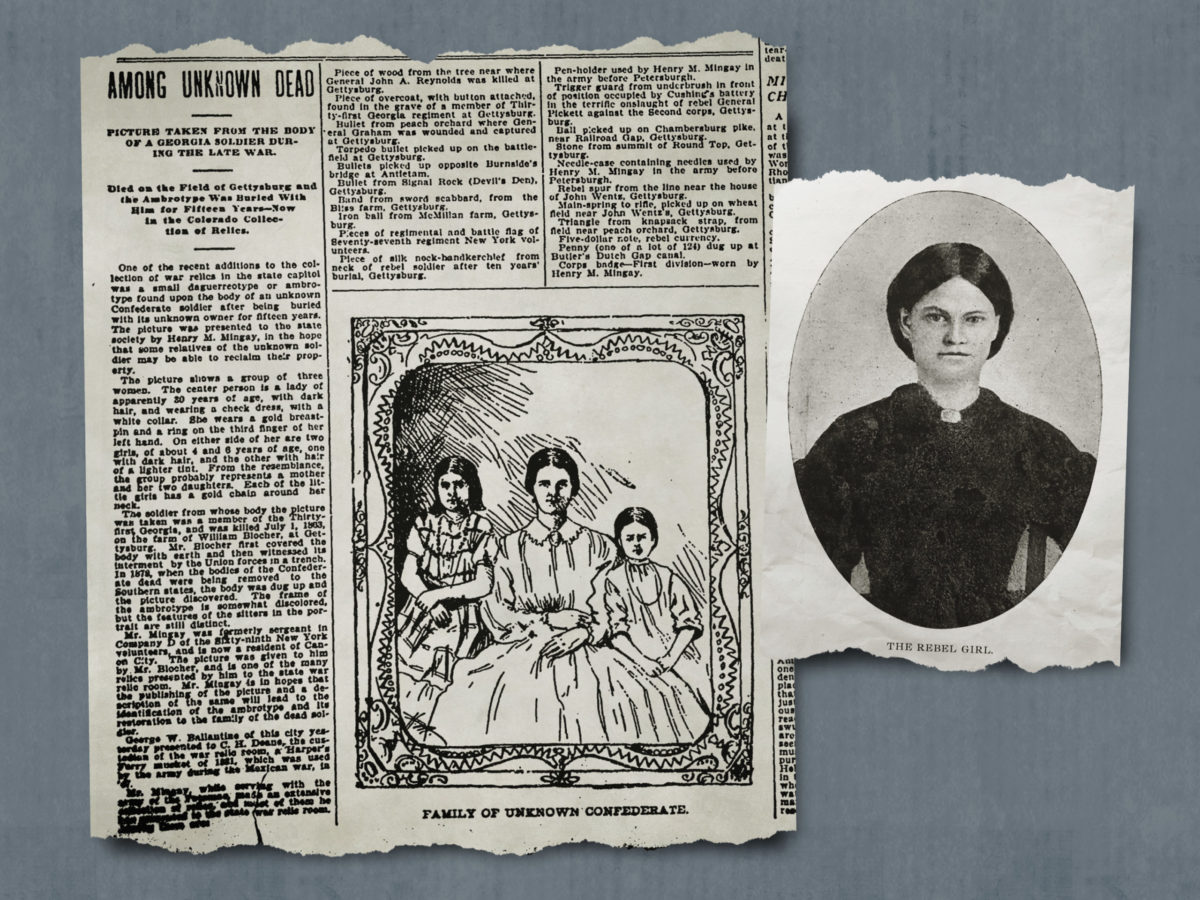

This letter is one of thousands of letters transcribed by William Griffing as part of his online repository of Civil War letters, Shared & Spared. For more of the compelling letters he makes available to read, visit the Spared & Shared Facebook page. This particular letter is from the private collection of Richard Weiner and is published with his permission.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Civil War photos and Letters

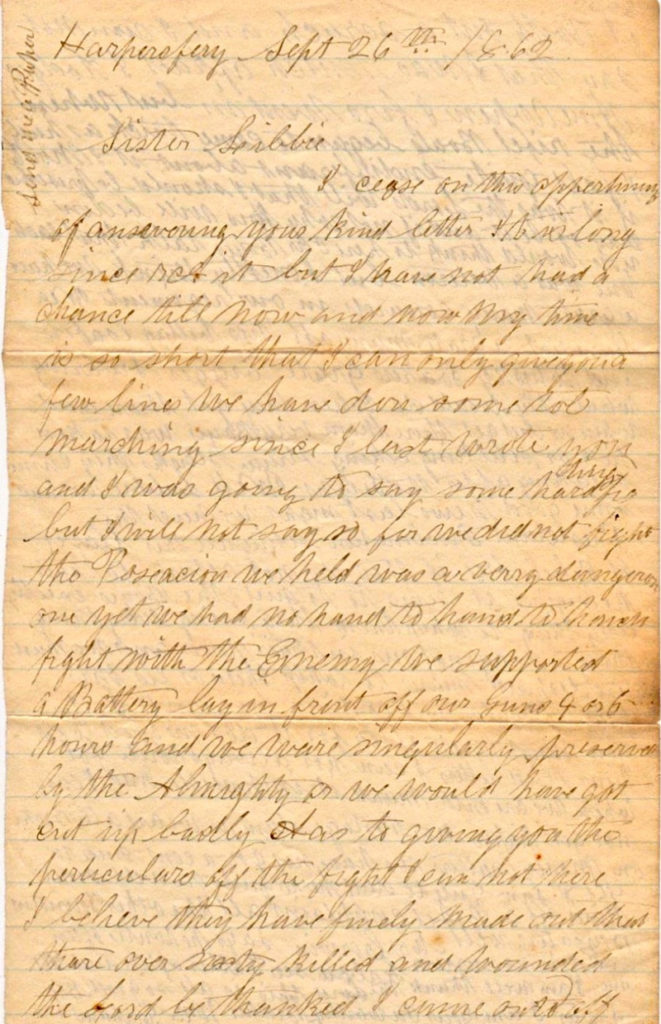

William Graham’s Letter

Harpers Ferry

September 26th 1862

Dear Libbie,

I seize on this opportunity of answering your kind letter. It is long since I received it but I have not had a chance till now. And now my time is so short that I can only give you a few lines. We have done some tall marching since I last wrote you and I was going to say some hard fighting but I will not say so for we did not fight. The position we held was a very dangerous one yet we had no hand-to-hand fight with the enemy. We supported a Battery. [We] lay in front of our guns 4 or 6 hours and we were singularly preserved by the Almighty or we would have got cut up badly.

As to giving you the particulars of the fight, I can not here. I believe they have finely made out that there [was] over sixty killed and wounded [in our regiment], the Lord be thanked. I came on & off it without a scratch and I cannot say that I was much afraid. I dodged some when I first when in but when the rifle bullets began to come thick as hail, I felt quite indifferent about it. I thought if it was the Lord’s will that I should be preserved, why so be it. And if not, why His will be done.

You would think to hear our boys talk that each one was a veteran but I honestly think we have a great many cowards in our regiment. We have got a great many of the village loafers and whiskey soakers — great braggarts — swearing what they would do when they got there [on the battlefield] and when we did get there, them very boys was taken sick or skulking behind straw stacks. They came sneaking [in] after the fight.

Well, Libbie, we had some good news. Last night we heard the President’s Proclamation setting all the slaves of Rebels free if they do not return to the [Union]. It seems to suit the boys exactly. Anything to whip them. They bring everything [to] bear against us in their power and we must use desperate means to whip them or else this manslaughter will continue for years.

Oh Sister, you must write often for it does me good to get your kind letters. I cannot always write for when we are on the march it’s impossible and I cannot get paper nor postage stamps. We are all broke on money matters. We have not got a cent since we left.

I saw Guy today. He is quite unwell — some kind of a bowel complaint. Says he writes often and gets no answer. Libbie, see Father often and tell him I am well, thank the Lord. This is all so goodbye, Sister.

I am your unworthy brother, — Wm. Graham

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.