Poor Kamala Harris. The vice president took office in January 2021 trailing a cloud of firsts: first woman to hold the job, first African American (thanks to her Jamaican father), first Asian-American (thanks to her Indian mother). But the job itself has been a cavalcade of vexations. President Joe Biden saddled her with an unattractive assignment—managing and explaining the migrant mess at the southern border. She is reputed to be hard on her staff in private, and she is often tongue-tied in public. Even media outlets friendly to the administration have run hit pieces on her. According to The New York Times, “dozens of Democrats in the White House, on Capitol Hill, and around the nation” said (anonymously) that “she had not risen to the challenge of proving herself as a future leader of the party, much less the country.”

The office of vice president was devised in the home stretch of the Constitutional Convention as a flywheel in the machinery for picking an executive, and a successor in case the president died or was removed from office. Along the way, Elbridge Gerry worried that veeps would be too closely allied to the presidents alongside whom they served, which provoked a snort from Gouverneur Morris: “the vice president will then be the first heir apparent that ever loved his father.” Initially the vice presidency went to the runner-up in the Electoral College’s vote for president; the 12th amendment (1804) ensured that the veep would be the running mate of the winning presidential candidate.

The office got off to a rough start. John Adams, first vice president under George Washington, was the first (though not the last) to feel that he had nothing to do. Thomas Jefferson, second vice president under Adams, spent his term undermining his old friend and plotting to supplant him. Aaron Burr, third vice president under Jefferson, was shut out of all patronage, denied renomination when Jefferson ran again, and spent his post–vice presidential years plotting to break up the United States.

Most modern vice presidents, beginning with Walter Mondale, Jimmy Carter’s number two, have been given substantive responsibilities, and have worked well with their number ones. Four of them—Mondale, George H.W. Bush, Al Gore, Joe Biden—have run for president themselves, two—Bush and Biden—successfully. But two vice presidents of an earlier era anticipated the problems bedeviling Harris today.

Henry Wallace was the scion of an Iowa family of farmer/journalists (they published a magazine called Wallace’s Farmer). His father served as secretary of Agriculture under Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge; Henry, crossing party lines, held the same job for FDR. In addition to his interests in crop cycles and new plant strains, Wallace had a passion for oddball religions. In the 1920s he came under the spell of Nicholas Roerich, a Russian émigré painter and seer who dressed in Tibetan robes and claimed to be the reincarnation of a Chinese emperor. Wallace and Roerich exchanged hundreds of letters, in which they referred to each other and to famous acquaintances in mystical code: Roerich was the Guru, Wallace was Parsifal or Galahad, FDR was the Flaming One, or the Wavering One, whenever Wallace felt disappointed in him.

In 1934 Wallace got Roerich attached to an Agriculture Department expedition to Mongolia seeking drought-resistant grasses. Roerich was also seeking the Holy Grail on the side. American diplomats reported that he was traveling the steppes with a bodyguard of White Russian Cossacks, trying to set up a Central Asian Buddhist kingdom. Wallace, embarrassed, cut ties with him.

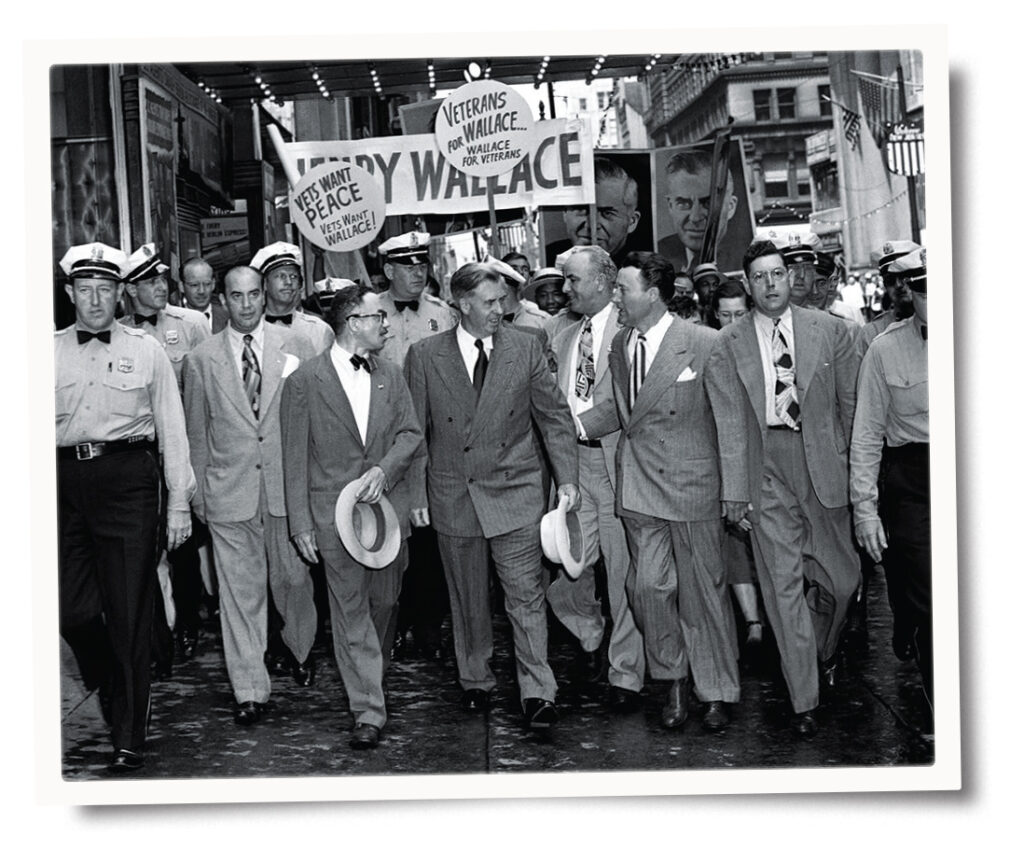

The Flaming One, tired of his crusty Texan veep John Nance Garner, tapped Wallace to be his running mate when he sought a third term in 1940. FDR wanted a man of liberal views, and Wallace fit the bill. One potential landmine threatened the new ticket. The Republican National Committee had procured copies of 120 Guru letters. The GOP candidate Wendell Willkie nixed using them, however, afraid that the Democrats would expose his long-running extramarital affair with a prominent New York journalist. Roosevelt and Wallace cruised to victory.

Wallace found new soul mates post-Roerich—American Communists, whose designs he naively failed to penetrate. The Soviet Union was a wartime ally, and Communists were billing themselves as liberals in a hurry. Alarmed Democratic bosses told FDR in 1944 that he must dump Wallace, so the nod for his fourth run went to Missouri Senator Harry Truman, who became president when Roosevelt died three months into his last term. When Wallace ran for president himself in 1948 as candidate of the left-wing Progressive Party, the Guru letters finally hit the papers. Wallace won a meager 2.4 percent of the popular vote, and carried no states. Repenting of his pro-Soviet backers, he lived until 1965.

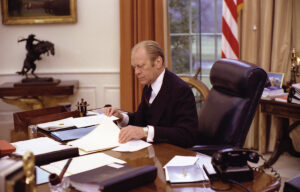

Richard Nixon was tied to Dwight Eisenhower politically and personally. He served as Eisenhower’s veep for two terms, 1953–1961. After Nixon won the White House himself in 1968, his daughter Julie married Ike’s grandson, David Eisenhower. Yet his relationship with Ike was always fraught.

Nixon had been put on the ticket in 1952 as a sop to the conservative wing of the GOP that Ike had defeated in winning the nomination. The two barely knew each other, however. There was a 23-year age gap between them. In September, the press revealed that Nixon had a campaign expense account, characterized in headlines as SECRET RICH MEN’S TRUST FUND. Ike’s advisers, fearful of any taint on the war-winning hero, pressured Nixon to resign from the ticket. Instead he made a half-hour television speech, defending his innocence (the account was legal), attacking Democrats (Ike’s rival, Adlai Stevenson, had his own campaign account), and pledging to keep Checkers, a cocker spaniel that a supporter had given Nixon’s daughters. The Republican National Committee got millions of letters, telegrams, and phone calls praising the put-upon Nixon. Ike embraced his feisty running mate.

But their relations never warmed. Nixon was intelligent and hard-working, but too political and ambitious for his old boss. In August 1960, at the end of Eisenhower’s second term and the start of Nixon’s first presidential run, against Sen. John F. Kennedy, the president was asked at a press conference what role Nixon had played in his administration. Had the vice president offered any “major idea” that Ike had subsequently adopted? “If you give me a week,” Eisenhower answered, “I might think of one. I don’t remember.” The Kennedy campaign gleefully used the line in an attack ad. Had Ike meant it as a flat-out diss? Probably not. But he hadn’t made a ringing endorsement either. The 1960 race was razor thin. Could a love-bombing Eisenhower have pulled Nixon over the line? Nixon would have to wait eight more years for a second shot.

The Vice President is a constitutional fixture and a political anomaly—a high official with hardly any defined role; a successor whom the president picks but cannot fire until and unless he runs again. Wallace was a deficient veep whom the president—and almost only the president—liked. Nixon was a work horse the president never truly admired. Kamala Harris seems to enjoy the worst of both worlds: low achievement, low esteem. With Biden determined to run again, will she be replaced a la Wallace, or retained a la Nixon? All the political termites of D.C. will be gnawing on that question.

This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.