Recommended for you

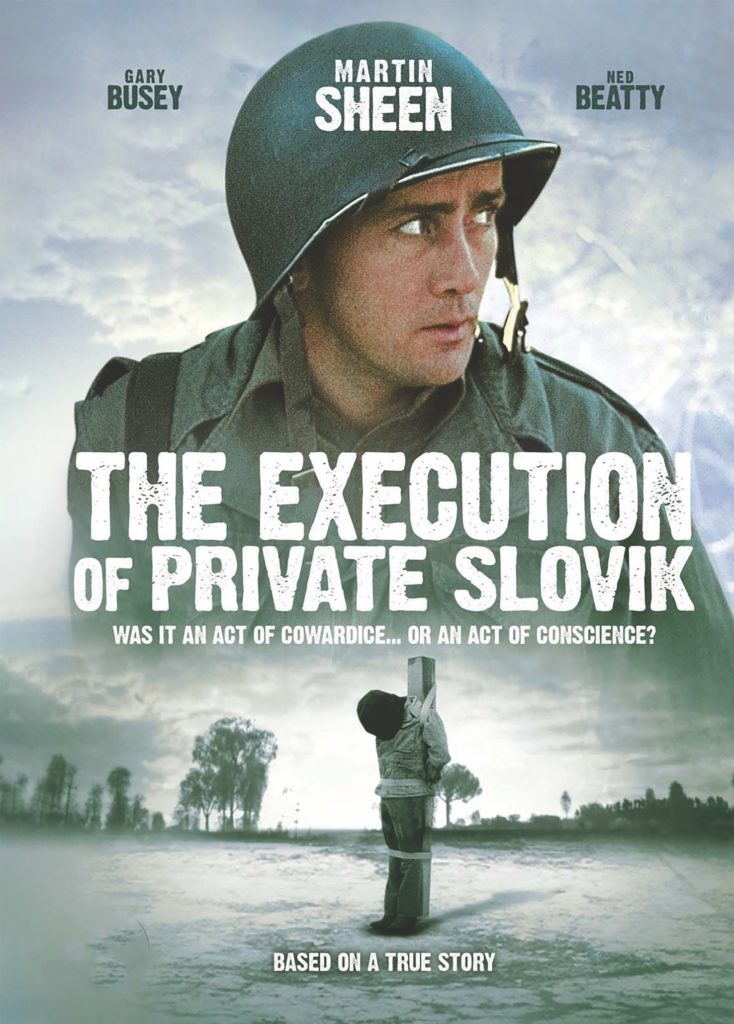

In March 1974, NBC conducted a major campaign to promote “the television event of the year!”—a made-for-TV film about World War II soldier Eddie Slovik, the only American shot for desertion since the Civil War. A large advertisement, widely placed in newspapers, showed a uniform-clad man standing, head bowed, as two soldiers tie him to a post in preparation for his execution, his plaintive expression somewhat reminiscent of a puppy in the rain. The ad left no doubt for viewers about how they should feel: “For the first time in his life,” its text read, “Eddie had a good home and a good woman. Suddenly—war, panic, a court-martial and…The Execution of Private Slovik.”

If this weren’t enough to tug at the heartstrings, the promotion continued: “Millions served. Thousands deserted. And one—only one in over a century—paid the full price for desertion. Why Eddie Slovik, who finally had something going for him?”

Why indeed? The answer is simple: never mind what Slovik had going for him. He got what was coming to him. Nobody made more sure of that than Slovik himself.

Directed by Lamont Johnson and starring Martin Sheen in the title role, The Execution of Private Slovik is far more nuanced—and powerful—than that treacly newspaper ad; the film respects its audience far too much to tell it how to feel. Its first 20 minutes focus not on Slovik, but on the hapless collection of infantrymen plucked from the front lines and saddled with the task of executing him. They have done their duty killing Germans in the heat of battle. Now their country demands that they must kill a fellow American in cold blood. They don’t like it. Neither does army chaplain Father Stafford (movingly played by Ned Beatty), who has been assigned the task of serving as Slovik’s spiritual adviser in his final hours but who also makes a point of providing pastoral care to the execution squad.

When Stafford prods the men to tell him how they feel about the job ahead, they are reluctant to speak. Finally one opens up: “If you want to know the truth,” he says, “all of us feel pretty bad about this,” adding that he tried to get out of the assignment. “He’s a deserter,” another man states without conviction. “Lots of men are deserters,” observes a third. “None of them have been shot.”

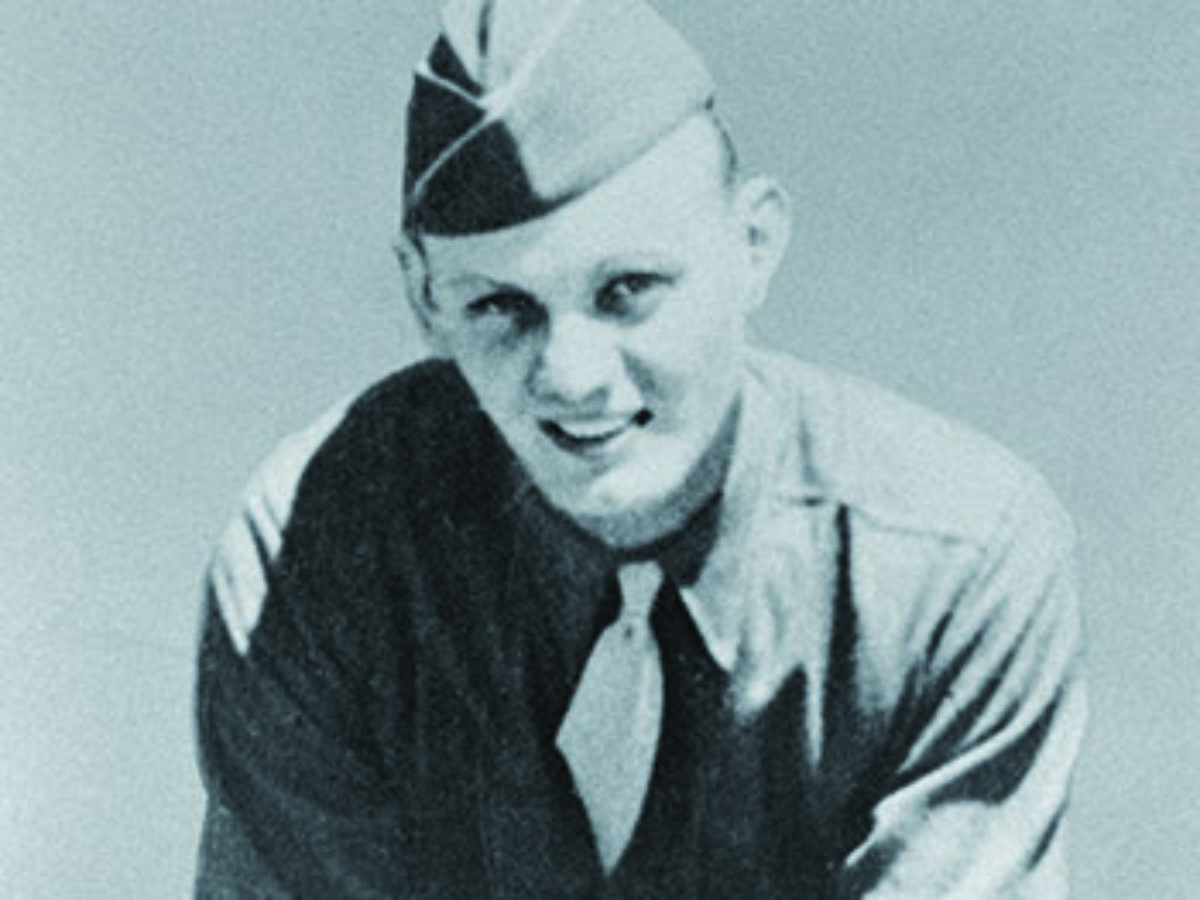

Eventually a truck arrives carrying a group of MPs along with the condemned man himself, 24-year-old Edward Donald Slovik of Detroit, Michigan. He is soft-spoken and courteous to his captors, who plainly think he’s a nice guy. He is a nice guy. The following flashback, comprising most of the movie, makes that abundantly clear.

The flashback kicks off several years earlier, with Slovik’s release from prison on parole following a string of minor crimes. He goes in search of an honest job and finds not just good employment but a good woman, Antoinette (Mariclare Costello), who soon becomes his wife. Slovik cares about Antoinette and the life they’re building together, and not much else; certainly not his country’s struggle to defeat the Axis powers.

The couple regards Slovik’s prison record as a shield from separation, since as a convicted felon he is automatically classified 4-F and exempt from the draft. But when heavy battlefield losses drive an urgent need for replacements, Slovik is reclassified as 1-A and conscripted into the army. He views this as inexcusably unfair; after vain attempts to get out of his service, he decides that if he must remain, he can at least make sure he survives to return to Antoinette. He deserts—not from a desire to escape, but with an urgent desire to get caught, figuring jail is preferable to dying in combat. He even writes an uncoerced confession stating that he has deserted. It promises, in all capital letters, that if sent to the front, he will desert again.

Slovik is court-martialed and convicted, which he expects, but is then sentenced to death, which is unsettling. He doesn’t believe he’ll be shot, but he figures that when the army commutes his sentence, he may end up in military prison a year or two longer than he calculated. After all, none of the other guys convicted of desertion have been shot.

True, but none of the other convicted guys ever tried to game the system so blatantly.

The Execution of Private Slovik insists that audiences empathize with Slovik, but it does not require that they view his fate as a miscarriage of justice. Slovik expected clemency from the army justice system, but clemency is an act of mercy, a magisterial show of forbearance by a powerful authority. Slovik did not see it that way. He mistook forbearance for weakness—and strength never permits itself to be confused with weakness, even when the person confused is a nice guy. And the men assigned to remove the confusion were—as the film makes clear—other nice guys who would rather have been anywhere else.