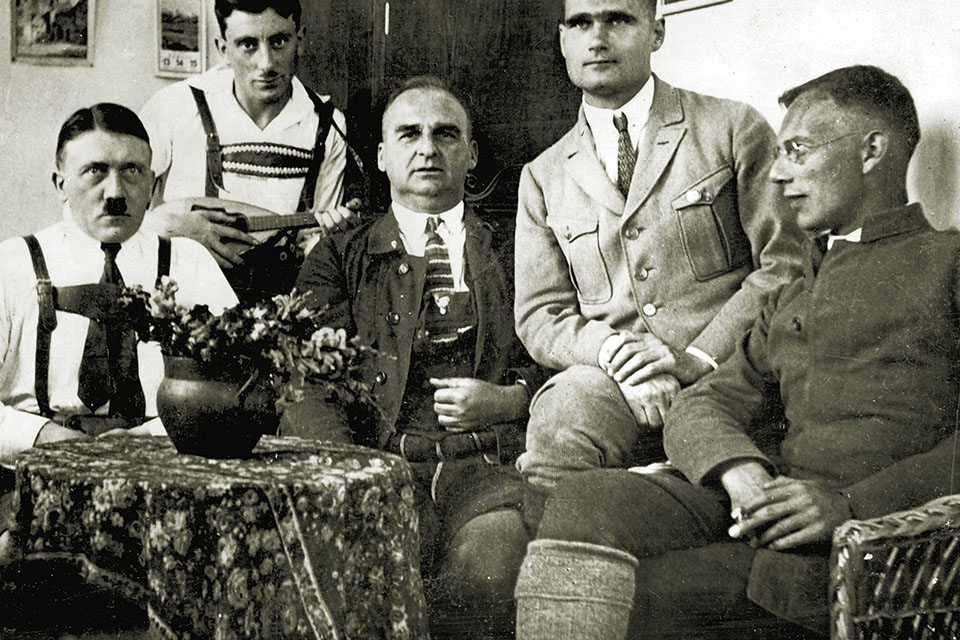

On a damp and windy day in late February 1932 presidential hopeful Adolf Hitler and his devotees in the National Socialist German Workers’ Party gathered in a secluded corner of a Munich café to discuss an article in Hamburg’s Social Democrat newspaper Echo der Woche. Headlined Kamerad Hitler, the piece suggested the rising star of German politics was not the World War I hero his followers purported him to be, but was in fact an Austrian deserter. The writer alleged that while serving on the Western Front, Hitler hadn’t come under enemy fire, as claimed, but had spent most of his time in the rear at regimental headquarters. The newspaper had withheld the writer’s name, ostensibly to protect that individual from retribution by Hitler’s Sturmabteilung paramilitary thugs.

By the early 1930s Nazi propagandists were on track to build Hitler into the Führer—a godlike supreme leader of the people. During his World War I service in the German army the Austrian-born soldier had received the Iron Cross (2nd and 1st Class) and the Wound Badge, thus his followers were eager to portray him as a hero who had risked his life for the Fatherland. Germany’s Social Democrats were as anxious to tarnish the war record of the “little corporal” by revealing any falsehoods or exaggerations.

In seeking to belittle the increasingly influential Nazi leader, however, those behind the article in Echo der Woche handed Hitler the perfect opportunity to take the “hero or coward” battle public by filing a libel lawsuit against the newspaper and its anonymous writer. In a libel action the person making the accusation—the newspaper, in this case—had to prove the claim was true. In addition, the court hearing the action would determine whether the reputation of the plaintiff—Hitler—had been harmed in the eyes of those who had read or heard the accusation. Unfortunately for the Echo, most of the witnesses called would testify on Hitler’s behalf.

Born in a small Austrian village on April 20, 1889, Hitler was the son of a minor civil servant the imperial government periodically transferred. Adolf was 5 years old when his father retired to a farm near Linz, where the family lived for several years. When his father died in 1903, the teenager experienced academic difficulties, though he ultimately graduated from secondary school. In 1907 young Adolf moved to Vienna to study art, only to be twice rejected by the Academy of Fine Arts. By year’s end his mother had died, leaving him an orphan.

In the fall of 1909 the empire issued a public decree via posters and newspaper notices requiring all Austro-Hungarian men born in 1889—the year of Hitler’s birth—to register for compulsory military service. Hitler later claimed to have duly reported to the conscription center in his district. “There I requested that I be allowed to report for military service in Vienna,” he wrote, “had to sign a deposition, or application, and pay one krone, and never again heard a word about the matter.” No such document has surfaced, though authorities had Hitler’s home address and could have picked him up, had they found cause. The destitute young bohemian lingered in town only long enough to collect his paternal inheritance. Before leaving for Munich in 1913, Hitler properly notified police of his planned departure, though he didn’t report his destination on the required form. By that fall Austro-Hungarian police were on his trail and sought the assistance of the Munich police in locating him.

On arrival in the Bavarian capital Hitler rented a shared one-room apartment on the third floor of a building owned by tailor Joseph Popp and family. Most mornings the street artist left quietly with his sketch pad and watercolor brushes to find local scenes to paint. He sold some works to acquaintances, such as customers at the popular coffeehouses where he often spent time drawing and indulging in a pastry with his tea.

One Sunday afternoon in January 1914 Hitler answered a knock on his door and was startled to find a Munich policeman, who presented the young man with a summons to appear in Linz within two days to register for Austro-Hungarian military service. The next day German authorities escorted him to the Austrian consulate. Taking pity on the thin, shabbily dressed young man, the consul general allowed Hitler to write a three-page letter to Austrian authorities, explaining his impoverished condition and apologizing for his failure to comply. “Despite great need,” he wrote, “I kept my name clean and am not guilty in the face of the law and have a clear conscience, except for the omitted military report, of which I did not even know at the time.”

Accepting his excuses, the consular official granted Hitler approval to take the required medical examination in Salzburg. He failed the physical. Filed at the State Registry Office, document “Nr. 786” noted, “Adolf Hitler, born on 20 April, 1889, in Braunau am Inn and resident of Linz, Upper Austria…was found by examination of the third age group in Salzburg on 5 February, 1914, to be ‘too weak for military or support service’ and was declared ‘unfit for military service.’” Though Hitler faced no fine or imprisonment for his initial failure to register, he was deeply embarrassed by the determination he was unfit for service. The document later proved a critical piece of evidence in the libel trial, proving Hitler was not a deserter from the Austro-Hungarian army. Regardless, some historians continue to argue the future German Führer was at the very least a draft dodger.

For his part, Hitler—whose abhorrence of the Hapsburg monarchy contrasted starkly with his near adoration of the German nation and its culture—expressed relief at having avoided service in the mixed-race Austro-Hungarian army. As he later wrote in Mein Kampf, the weak-kneed policies of the Austro-Hungarian empire aimed at “Germanization of the Austrian Slavs” would only lead to “a destruction of the Germanic element.” On his return to Munich he resumed his meager existence painting and selling watercolors of local scenes, spending much of his free time browsing newspapers in local cafes to brush up on foreign events and national politics.

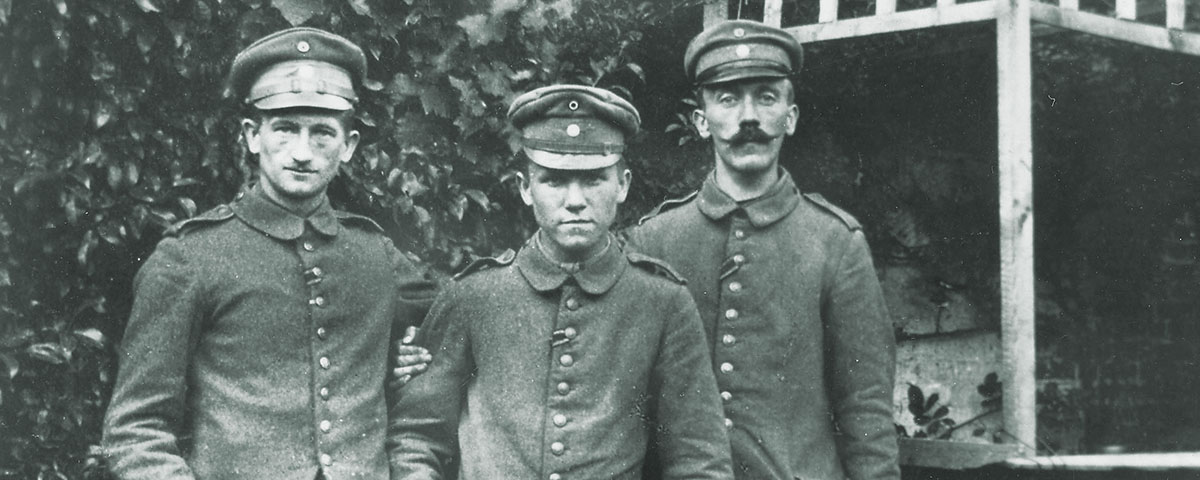

Though still a citizen of Austria-Hungary, Hitler joined the millions of Germans who welcomed news of their nation’s declaration of war on imperial Russia and its allies on Aug. 1, 1914. Many believed war would bridge the long-standing domestic political divisions and finally unite the Germanic people. On August 3, the day after attending a huge patriotic gathering in Munich’s Odeons-platz, Hitler volunteered for service in the Bavarian army, a constituent part of the German imperial army. On August 16 he was summoned to his local recruiting office and directed to join the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, aka the List Regiment. Despite the rigors of training, Hitler found his new life exciting, and early on October 21 he joined his comrades on a train bound for the Western Front. As the morning sun rose over the misty Rhine River, the embarked troops began singing the patriotic anthem “Die Wacht am Rhein.”

“I felt as though my heart would burst,” Hitler recalled.

The picture of Hitler going off to war as an enthusiastic volunteer was far from the image presented in the Echo der Woche article of a “deserter” who spent his time at the front in the relative comfort and safety of regimental headquarters. Unfortunately for the newspaper’s lawyers, they had to work with a writer who insisted on remaining anonymous and were able to find only a single veteran willing to confirm the allegations.

Part of the problem for the defense in the libel case stemmed from semantics. First came the question of whether Hitler had served “in the trenches.” The fact was, there were countless miles of trenches, some in proximity to the enemy, others far removed from immediate danger. Then came the matter of how long a soldier had to be at the front to qualify as having “served” there. And while there were certainly distinctions between frontline trenches and rear-area regimental headquarters, both could be killing zones. Would anyone, let alone a court of law, think less of Hitler were it proven he’d been wounded 2 miles to the rear versus at the front?

In fact, Hitler spent about a month in the front lines as a rifle-carrying infantryman. That November his regimental headquarters assigned him to serve as a dispatch runner and promoted him to Gefreiter, the equivalent of lance corporal. But he wasn’t out of danger.

Dispatch runners typically carried messages over considerable distances. The German lines usually comprised three trenches, each about a half-mile apart and connected to the others by zigzag communications trenches. Typically 12 feet deep, the trenches were often reinforced with wooden slats or sandbags and featured elaborate redoubts. Some delved as deep as three stories, with concrete steps and rooms with cupboards, furniture and electric lights. Yet despite the strength and depth of the German fortifications, the entire trench network—forward, middle and rear—and the regimental and brigade headquarters in villages behind the lines were exposed to mortar and artillery fire. Dispatch runners were in constant peril from enemy fire. One of Hitler’s fellow runners, Balthasar Brandmayer, later described a perilous run the pair undertook between regimental headquarters: “Grenades chased us through the darkness of the night; we rolled in time with them into a water-filled mine crater.…‘Now, push on!’ said Hitler, and we scrambled up the crater wall.” That said, there were quiet days, Brandmayer conceded, when even Hitler would say, “Today an old woman would have had no trouble in getting through.”

Frontline infantrymen dubbed those stationed behind the lines “rear-area pigs,” the fortunate few who rolled in comfort compared to their own squalid existence amid knee-high mud and unending storms of shells and bullets. Such a label might haunt a man with postwar political aspirations.

Thomas Weber, the author of Hitler’s First War, is among those who question the heroics of Hitler’s service. One discrepancy Weber points to is Hitler’s claim in Mein Kampf to have been “wounded as a frontline soldier rather than in regimental headquarters in a village 2 kilometers behind the front.” But if Hitler’s account was an embellishment, it isn’t clear he intended it as such. His exact words were, “On Oct. 7, 1916, I was wounded but had the luck of being able to get back to our lines and was then ordered to be sent by ambulance train to Germany.” Hitler and other runners were reportedly in a dugout in Le Barque when he was wounded and taken to the nearest field hospital, at Hermies, some 10 miles farther east. Although Hitler gave the date as October 7, the regimental casualty list records he was wounded on October 5. Statements from his comrades regarding the incident also differ on the specifics. Private Ignaz Westenkirchner testified that when the shell hit their dugout, the explosion killed four and wounded seven others, including Hitler, whose face was gashed by shrapnel. Westenkirchner said that incident occurred on October 2, while on October 7 Hitler was wounded in the left leg.

An account by another of Hitler’s comrades described the incident as follows:

The message runners were in an underground passage that was so narrow and low that two people could not pass each other. You could hardly sit. We kept tripping over each other’s legs. The air was so thick and heavy you could barely breathe. A small stairway led outside. I had just sat down next to Hitler when the passage took a direct hit. The roof was demolished and torn into a thousand pieces. Shrapnel flew everywhere.

According to the witness, several men were wounded, including Hitler, who was carried to the field hospital at Hermies with shrapnel in his left thigh. Doctors sent him and fellow wounded runner Ernst Schmidt by ambulance train to a military hospital within 30 miles of Berlin.

Hitler spent two months in the hospital, then traveled to Munich for further recuperation. He spent Christmas with List comrades also on wounded leave. But Hitler was anxious to return to his unit at the front. “It is my pressing wish,” he wrote the regimental adjutant, “to be with my old regiment and old comrades.”

In 1932 Hitler’s attorney found several veterans—fellow soldiers and superiors alike—willing to testify about their comrade’s honorable service. “[Hitler] was a dispatch runner for the staff of the [List] Regiment,” affirmed Wilhelm von Luneschloss, former commander of 3rd Battalion, “and had truly proved himself as such. Hitler never failed and was particularly suited to the tasks that one could not give to the other dispatch runners.” Among the most credible of the character witnesses was Michel Schlehuber, who had known Hitler since the outset of the war. Schlehuber recalled him as a “good soldier and faultless comrade” who never shirked any duty or danger. While the testimony was similar to that others had given, it carried more weight, as Schlehuber was a Social Democrat and longtime trade union member—certainly no supporter of the Nazis.

Of course, in defending his record as a valiant soldier, Hitler’s comrades in arms also preserved their own honor. One of them, Hitler’s friend and fellow runner Schmidt, remained steadfastly loyal through the war years. At the time of the libel trial the young men, who were the same age, remained in contact and would occasionally meet at a restaurant to share a meal and memories of the war. Schmidt had joined the Nazi Party in the early 1920s and later became deputy mayor of his small town. His friendship with Hitler came to light in 1945 when Allied interrogators interviewed Schmidt.

In the end, given the steadfast backing of such former comrades and the Echo writer’s refusal to testify or even reveal his identity, the newspaper’s attorneys didn’t stand a chance. The court ruled the paper had indeed committed libel against Hitler. Usually a lost libel case resulted in a monetary fine for the defendant, so it is probable the publishers of the newspaper had to pay Hitler’s attorney and issue a public retraction.

A year after the trial Brandmayer wrote a memoir about comrade Hitler, in which he described their first encounter at the front. “He had only come back fatigued after a delivery,” Brandmayer wrote. “I looked at him for the first time in my life. We stood eye to eye, facing one another.…He was like a skeleton, his face pale and colorless. Two piercingly dark eyes, which struck me especially, stared out of deep sockets. His prominent mustache was unkempt.” While the veracity of Brandmayer’s memoir is shaky in spots, his description of Hitler does include a telling detail. “There was no man under his uniform,” the author wrote. “He had an iron nature.”

Despite Nazi propaganda portraying Hitler as a hero, the man himself never claimed such a distinction. In fact, he admitted sharing the fear of his comrades. “A time came,” he wrote in Mein Kampf, “when there arose within each one of us a conflict between the urge to self-preservation and the call of duty.” In a letter dated Feb. 5, 1915, Hitler wrote to Ernst Hepp, a Munich lawyer who had helped him before the war, again confessing weakness: “From 8 in the morning to 5 in the afternoon, day after day, we are under heavy artillery fire. In time, even the strongest nerves are shattered by it. I keep thinking about Munich.” Some comrades recalled Hitler’s anxiety. “As soon as serious firing would begin,” one wrote, “he acted like a racehorse before it has to start…walking around restlessly, buckling on his equipment.” Nearly a decade after the war, while languishing in Landsberg Prison after the failed Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler broke down in tears while recalling to his Nazi Party deputy, fellow inmate and Mein Kampf transcriber Rudolf Hess how frightened he’d been in the midst of combat.

So, although Hitler wasn’t the cowardly deserter depicted in the Echo, neither was he the heroic martyr Nazi propagandists sought to enshrine years later. Yet his rivals’ slander worked in Hitler’s favor. The libel lawsuit was just one example of the countless times the Nazis exploited the courtroom for publicity, receiving the ostensible approval of the Weimar judiciary and keeping on the right side of the law as they pursued the politics of global domination with Hitler as their iron fist.

Suzanne Pool-Camp is a freelance writer based in Fredericksburg, Va. The coauthor of Who Financed Hitler (1978), she is writing a book about Nazi legal battles during the Weimar Republic. For further reading she recommends Hitler’s First War, by Thomas Weber; Private Hitler’s War, by Bob Carruthers; and A Storm in Flanders, by Winston Groom.