The Fisher XP-75 Eagle was the worst aircraft that U.S. taxpayers bought during World War II. When the P-75 program was finally shut down in October 1944, only 14 unarmed, useless aircraft had been manufactured. Estimates vary wildly as to how much each airplane cost, but the kindest guess is about $9,375,000 in 2020 dollars. (The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, which the P-75 was intended to replace, went for roughly $1.2 million in today’s dollars.)

How could this have happened? Blame it on stupidity, greed, poor management, an unfortunate engine choice and an overrated aircraft designer.

By the time the United States entered the war in December 1941, it was clear that traditional ideas about air combat had become outmoded. Short-legged, medium-altitude bomber interceptors weren’t going to be of much use. The U.S. military needed long-range, fast-climbing, high-altitude escort fighters that could outfly the best that the Germans and Japanese could be expected to develop, and it needed them right away.

The War Department had mobilized Detroit’s car manufacturers to build tanks, guns and airplanes. Ford built the largest factory in the world at Willow Run to crank out B-24 Liberator bombers (though industry adviser Charles Lindbergh called early-production units the worst examples of metal aircraft construction he had ever seen). General Motors had quickly established an entire new division, Eastern Aircraft, to produce Wildcats and Avengers for the Navy.

GM execs had the bright idea of designing their own fighter under the brand name Fisher, to be manufactured by their body-building division. They followed that up with the stupid idea of creating it from already-built components of existing airplanes, so that it could be slapped together in six months with a minimum of engineering. Curtiss P-40 wings, Douglas Dauntless rear fuselage and empennage, Vought F4U landing gear…why not? GM knew that you could put a Pontiac engine in a Buick or Cadillac suspension on a Chevy chassis, so there should be no reason the same mix-and-match technique wouldn’t work for an airplane, right?

Ignored was the fact that wings aren’t just the big flat things that poke out of the fuselage, they are carefully engineered to maximize performance without excess drag, matched as well as possible to the airframe they support. Nor are tailfeathers just the pointy surfaces back aft, they are engineered to help create each airplane model’s stability and controllability with the least drag.

Not surprisingly, the a la carte manufacturing approach was initiated by a car guy: William Knudson, former president of General Motors—yet another GM finger in the pot—who had been put in charge of the U.S. government’s war procurement and production programs. Knudson believed that the country’s aircraft builders needed to learn to interchange major components, just as the car manufacturers did.

GM’s Don Berlin signed on to this idea. History gives us no clue why a seemingly intelligent aircraft designer and engineer would buy into such a kludge…other than to keep his job.

Berlin was well known as the designer of the P-40, the Army Air Forces’ obsolescent frontline fighter. The P-40 was a re-engining of Berlin’s 1938 P-36 Hawk, which could be called his last good design. At Curtiss he had gone on to create the unstable Seamew Navy floatplane and the canard XP-55 Ascender, quickly dubbed the Ass-Ender thanks to its pusher engine. Berlin then quit Curtiss and was hired by GM, which was told by the War Department that it needed a big name as part of its aborning fighter program.

GM knew that it had to use the most powerful engine it could find if it was to achieve the performance the AAF was requesting: 440 mph top speed, a 38,000-foot ceiling, 2,500-mile range and a remarkable 5,600 feet per minute initial climb rate. Pratt & Whitney and Curtiss-Wright had powerful contenders under development, but so did Allison, which happened to be owned by GM. So the Allison V-3420 (actually a W configuration rather than a V) became by default the heart of the XP-75.

The 2,600-hp V-3420-B was two V-1710 engines—the familiar P-38/P-39/P-40 power plant—on a common crankcase. But it had two crankshafts, and cranks are the heaviest part of a piston engine. The crankshafts counterrotated, spinning two 15-foot-long driveshafts, which transitioned into a single propshaft through a large, heavy gearbox in the airplane’s nose. In the P-75A, the engine sat behind the cockpit, like a P-39’s Allison V-12, and the driveshafts ran under the pilot. Further complication was created by the need for two enormously complex contrarotating propellers to absorb the V-3420’s horsepower. (Four of the P-75’s never-installed 10 .50-caliber machine guns were in the nose, firing through the props. Imagine the complexity of an interrupter mechanism choosing clear spaces between such a Cuisinart of prop blades.)

The V-3420 was never intended to be a fighter engine. It was too large and heavy, and was initially developed to power a very long range, very heavy four-engine intercontinental bomber. The new V-24 could have used the multiengine redundancy, too: At one point, the AAF proudly reported that the V-3420’s reliability was much the same as that of two V-1710s—another way of saying the V-24 would fail twice as often as the V-12.

One of the V-3420’s major problems was uneven mixture distribution between its four banks of carbureted cylinders, all four fed by a single supercharger through just two induction trunks. This necessitated running the engine at a setting that would not cause detonation in the leanest of those 24 cylinders, thus impacting both power and fuel efficiency.

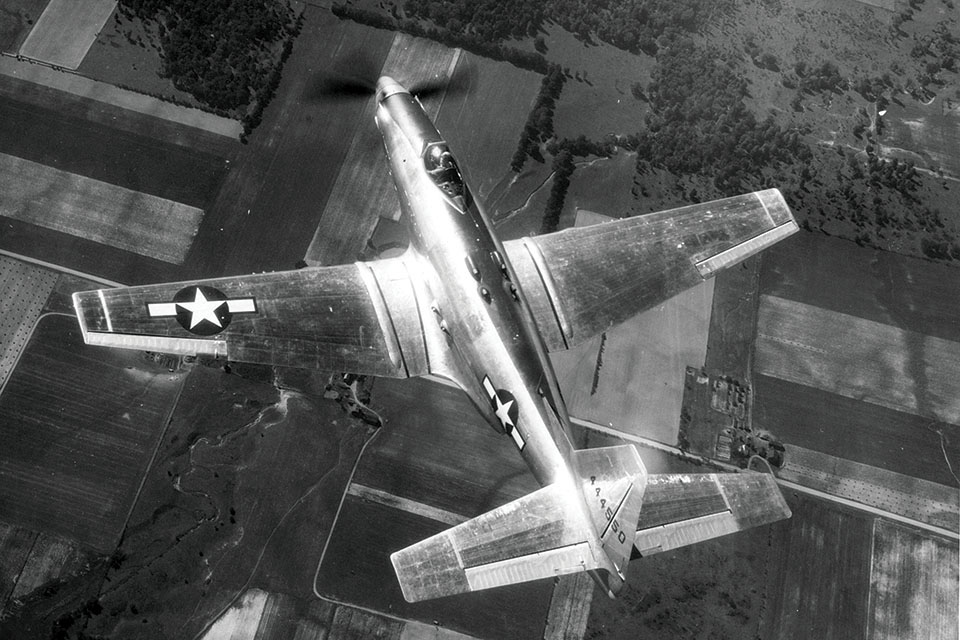

Lumbered with an underperforming experimental engine, the Fisher P-75 was fated to fail. In an inverse affirmation of the old cliché “If it looks good, it’ll fly good,” the P-75 looked clumsy and flew badly. Slow and unstable, it would stall and spin during standard dogfighting maneuvers.

Never an Eagle, it was certainly a turkey.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!

Ready to add a replica of this unique aircraft to your own collection? Click here!