On the afternoon of Friday, September 6, 1901, President William McKinley was in Buffalo, New York, shaking hands with well-wishers at the Pan American Exposition when an assassin shot him. The gunman, an unemployed factory worker, had been following McKinley for two days. Gravely wounded, McKinley fought for eight days to stay alive. The president’s much-ballyhooed presence at the inland port had attracted numerous camera wielders, professional and amateur. After McKinley died many of those photographers believed they had made the last exposure before the fatal moment.

Photography had come a long way. In 1827, when Joseph Nicéphore Niépce made a study of a street in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France, that he titled Le point de vue du Gras (“View from the Window at Les Gras)”, his camera’s shutter, which made an image by letting light strike photosensitive material, had had to stay open for hours; anything in frame that moved appeared in the resulting print as a blur. Over decades exposure times shrank to minutes, but photographic portraitists’ subjects still had to keep deathly still, sometimes using armatures. As early as the 1850s, however, leaps in technology and technique were making possible faster exposure times and more natural-seeming images. Thomas Skaife’s Pistolgraph pioneered the concept that smaller lenses and image areas, requiring less light, could further shrink exposure times. Skaife’s use of wet plates and smaller negatives had this effect. His camera suggested a handgun, with the lens for a barrel, a resemblance said to have caused his arrest while he was attempting to photograph Queen Victoria with a Pistolgraph. Loading and processing glass and metal plates and sheet film, which required noxious solutions and total darkness, remained cumbersome and costly. Plates had to be inserted and removed from the camera one by one and, until processed, always shielded from light.

In 1884, George Eastman of Rochester, New York, invented roll film, which, when fitted into an apparatus within the camera, advanced mechanically from one exposure to the next until the roll had run out. Roll film obtained its flexibility from nitrocellulose, or guncotton. In 1888 Eastman founded a company to mass-produce his cameras and the roll film they used, and also to process the results into negatives and prints. Eastman named his company after himself and dubbed his box camera the “Kodak” because that nonsense word could be pronounced in any language. Customers mailed exposed film in the camera to Eastman Kodak, receiving in return prints, negatives, and another camera loaded with film and ready to use. “You press the button,” Kodak advertised. “We do the rest.” Camera sales and use soared as Americans took up this new and exciting activity as a hobby or as a profession.

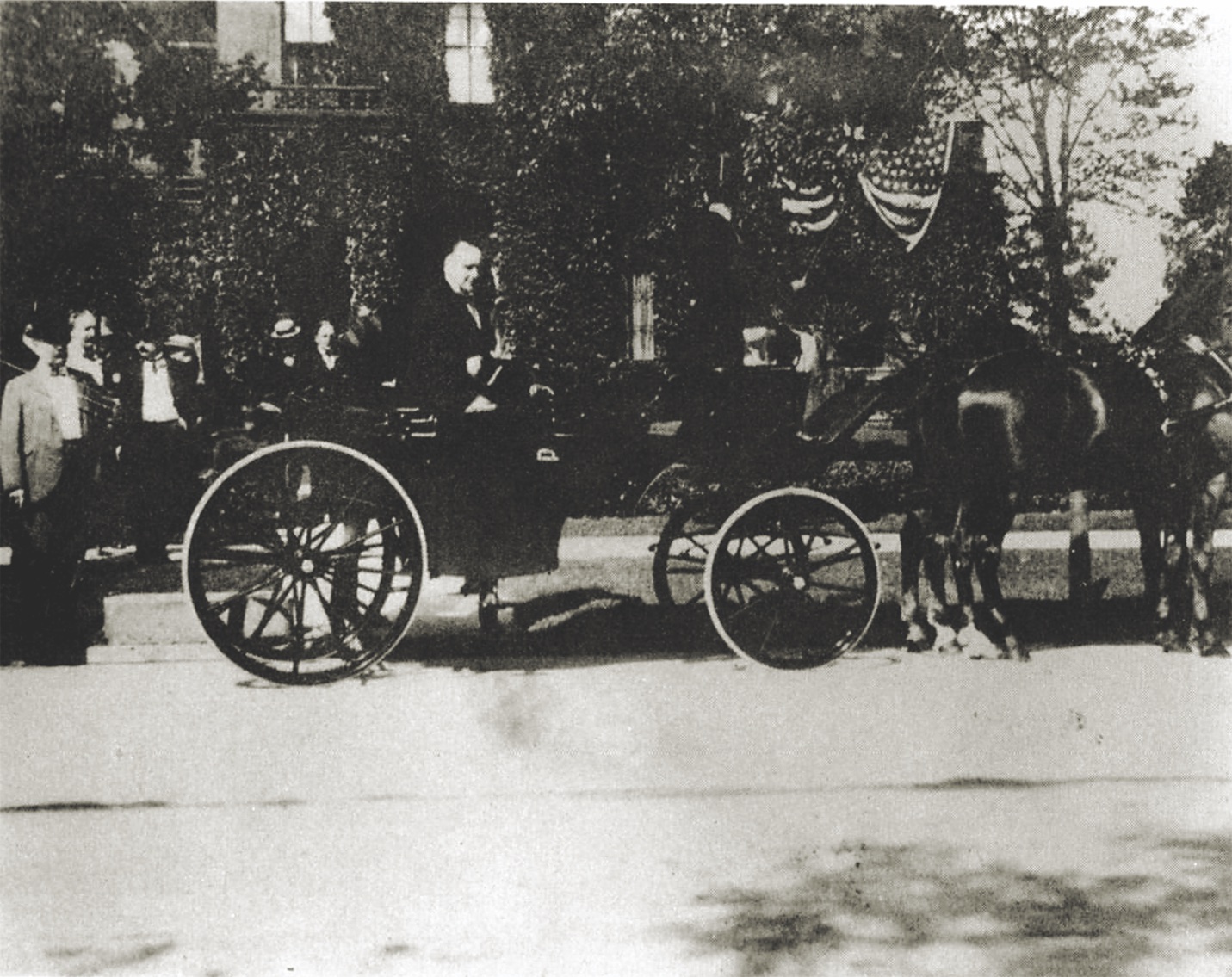

One hobbyist was Buffalo resident Hermann A. Brunn, 26, who on Thursday, September 5, 1901, had gotten out his camera to do a favor for his uncle. Henry Brunn was Buffalo’s leading coach builder and his nephew’s employer. For the duration of William and Ida McKinley’s two-day visit, Brunn Carriage Manufacturing Co. was loaning the presidential party a horse-drawn landau painted a deep wine red with upholstery to match. The carriage maker’s nephew assigned himself to document this coup for posterity. “I was very much interested in amateur photography,” Brunn later told the Buffalo Courier Express. “It occurred to me that it would be very interesting to secure a picture of President McKinley in our carriage.” At the renowned stable on the grounds of Buffalo businessman and horse breeder Harry Hamlin’s home on Delaware Avenue, Brunn learned from coachman James McGee where and when the landau driver was to fetch his famous passengers. “Knowing the police would be on guard I went to No. 6 Police Station and through Sergeant Hurley obtained permission to pass the lines of police with my camera,” Brunn told the paper.

The McKinleys, nearing the end of a transcontinental round trip, had arrived the night before by train at the railway station located at the northern end of the Exposition grounds. They were the house guests of Exposition president John G. Milburn, who also lived on Delaware Avenue, less than two miles from the fairgrounds. A little before 10 a.m. on Wednesday, September 5, young Brunn, camera in hand, was teetering atop a stepladder across Delaware Avenue from the Milburn residence. Mrs. McKinley, carrying a parasol, was stepping out through the front door when a file of mounted police officers moved into position, obstructing Brunn’s view. He abandoned his ladder. Edging between horsemen, he stepped into the middle of the roadbed, observed by Secret Service agent George Foster, assigned to protect the McKinleys.

As Brunn was tripping his shutter, Foster instinctively moved toward the curb. “As I looked into the camera I saw the sun shining on Mr. McKinley’s head,” Brunn said. “He stood hat in hand bowing to the people. The picture shows that the exposure was made at the very moment that Mr. McKinley raised his hat.”

Deemed “President’s Day,” September 5 was the focal point of the leader’s visit, centered around a speech he gave that afternoon in the center of the Exposition grounds. An estimated 50,000 people attended the event, often referred to as one of McKinley’s finest orations, in which he spoke of the nation’s “unexampled prosperity” and predicted an end to American isolationism. There to document the moment was the exposition’s official photographer, Charles D. Arnold.

Arnold, who had had the same role at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, held the photography concession for the Pan American. He enjoyed exclusive rights to photograph on the Exposition grounds. Other photographers on the grounds faced restrictions. “No cameras exceeding four by five inches shall be allowed within the gates,” the rules stated. “Stereoscopic cameras and tripods will not be admitted under any circumstances. The fee for the admission of cameras four by five inches or under will be 50 cents for a day or $1.50 for a week.”

Not a few photographers thought the pickings were good enough to submit to the costs and controls. Famed landscape photographer B.W. Kilburn was there making numerous stereoscopic images of the President giving his speech. Motion picture men Edwin S. Porter and James H. White of the Thomas Edison Co. had brought a tripod-mounted spring-driven camera to document the President’s movements at 40 frames per second. Francis Benjamin Johnston had her Kodak No. 4 Bullseye at the ready.

The Washington, DC-based Johnston was working as McKinley’s official photographer, as she had for predecessors Cleveland and Harrison, and also had spent the summer under contract to the Buffalo Express documenting the Exposition. During her boss’s speech Johnston stayed close to the stage, exposing one of the most enduring images of McKinley. When he finished speaking the crowd dispersed.

Friday was dedicated to the urgent official leisure that presidential visits often occasioned. Thursday morning’s Buffalo Courier Express carried McKinley’s schedule, beginning with “8:15 A.M.—The President and party accompanied by mounted escort will drive from the Milburn home.” Across town Leon Czolgosz, who had been boarding for a week at Nowak’s Saloon on Broadway Avenue, read the paper. Czolgosz, an avid consumer of news, had come to Buffalo from Illinois prompted by another article. “Eight days ago, while I was in Chicago, I read in a Chicago newspaper of President McKinley’s visit to the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo,” Czolgosz testified later. “That day I bought a ticket for Buffalo and got here with the determination to do something, but I did not know just what.”

As had been the case on Thursday, Friday morning was sunny, prompting Ida McKinley, departing the Milburn house, to deploy her parasol again. Again, her husband, playing to the cameras, smiled and tipped his hat. Among that morning’s lensmen was Robert L. Dunn. Just shy of 27, Dunn had been assigned by Frank Leslie’s Weekly to cover the McKinleys’ excursion from Washington to San Francisco and back. Dunn was a comer. A colleague described him as “American every inch, a Tennessee man, trained in New York, he will do anything, bear anything, go anywhere, to get a beat.”

The McKinleys’ second day in the lakeside city was to consist mostly of a tour of nearby Niagara Falls State Park. From Exposition Railway Station a train would shuttle the couple to Lewiston, miles downstream of the park, where their party would board a rail car carrying them along the scenic gorge route to the falls. At the cataract the guests would ride around the park in a carriage to Prospect and Terrapin Points and other overlooks as well as visit Goat Island, which marks the Canadian-American border at the falls. The president and his entourage would lunch at the nearby International Hotel, then call at a newly built plant harnessing Niagara’s power for electricity. The six-hour circuit was to deliver the McKinleys to the Exposition grounds for a public reception at 4:00 pm.

As the McKinleys were leaving the Milburn house Friday morning, Dunn framed them yet again. So did John D. Saulsbury of Batavia, New York. Subsequent reports, including one in the Batavia Daily News headlined “John D. Saulsbury Slave to Morphine,” characterized the lensman, who was around 24, as a “soldier, photographer, electrical engineer, chemist and counterfeiter.” In 1899 Saulsbury had enlisted in the Army Signal Corps. Assigned to cover the Philippine insurrection as a combat photographer, he was taken prisoner by insurgents in Manila. “During my service in the Philippines I took about 27,000 pictures,” Saulsbury recalled. “About 400 of these were on exhibition at the Pan-American Exposition.”

The Exposition originally was to occur in 1899 on Cayuga Island at Niagara Falls but in 1898 the United States had gone to war with Spain, delaying the event. After the war Buffalo challenged Niagara Falls as the Exposition site and won the opportunity thanks to a larger population and superior railroad connections. The rescheduled Exposition occupied 350 acres of farmland north of town. In 1901 Buffalo—the country’s eighth largest city—was reveling in prosperity gained in 75 years as the junction between the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes. Location and ambition had made more millionaires per capita there than in any other American city, with Harry Hamlin, John G. Milburn, and others lending Delaware Avenue the sobriquet “Millionaire’s Row,” while at the same time seedy, harborside Canal Street bore the tag “the most dangerous street in the world.”

The city fathers planned the Exposition to showcase their bustling town, America’s Gilded Age, electricity’s promise, and the nation’s martial eminence. The scale meant to impress. “The spectator, as he approaches the Exposition, will see it develop gradually until he reaches the Bridge, when the entire picture will appear before him and almost burst upon him,” head architect John M. Carrère wrote in the 1901 Art Catalogue to the Pan-American Exposition. The main gate led to the Triumphal Bridge and the Court of Fountains, flanked by the ornate Temple of Music and Ethnology Buildings, themselves dwarfed by the 389’ Electric Tower. By night the entirety glowed and buzzed amid spectacularly electric illumination.

Friday morning President McKinley passed through all that splendor on his way to the Exposition Railway Station to catch his 9 a.m. train to Lewiston. At the rail station gate Leon Czolgosz was waiting, hoping for a chance to get close to the president. “I waited near the central entrance for the President, who was to board his special train from that gate,” he said later. “But the police allowed nobody but the President’s party to pass where the train waited, so I staid [sic] at the grounds all day waiting.”

In Buffalo, Czolgosz’s intentions had solidified. As of Tuesday he had resolved to kill William McKinley. At Walbridge’s Hardware downtown, he paid $4.50 to purchase a .32-calibre Iver Johnson Safety Hammer Automatic Revolver. He may or may not have trailed the presidential party to Niagara Falls; in any event, it came to him that the 4 p.m. public reception in the Temple of Music would offer him his best shot. The McKinleys arrived in Lewiston with Leslie’s Weekly photographer Dunn, as ever, close by. As the couple was exiting their rail car Dunn exposed a frame. At Dunn’s side and at nearly the same second competitor Jimmy Hare, working for Collier’s Weekly, did the same.

James H. Hare, 45, had grown up in London, England, where he worked for his father. Camera manufacturer George Hare, whose business was large-format tripod-mounted rigs, abhorred the burgeoning trend toward the small, portable “hand cameras’’ that fascinated his son.

Leaving his father’s employ, the younger Hare became a photographer. In 1884, using a hand camera, he made what some refer to as “the first snapshot,” showing a hot-air balloon aloft. The phrase dates to an 1860 article by British inventor John Hershel about “instantaneous photography” in which Hershel repurposed a term hunters employed to mean “a quick shot with a gun, without aim, at a fast-moving target.”

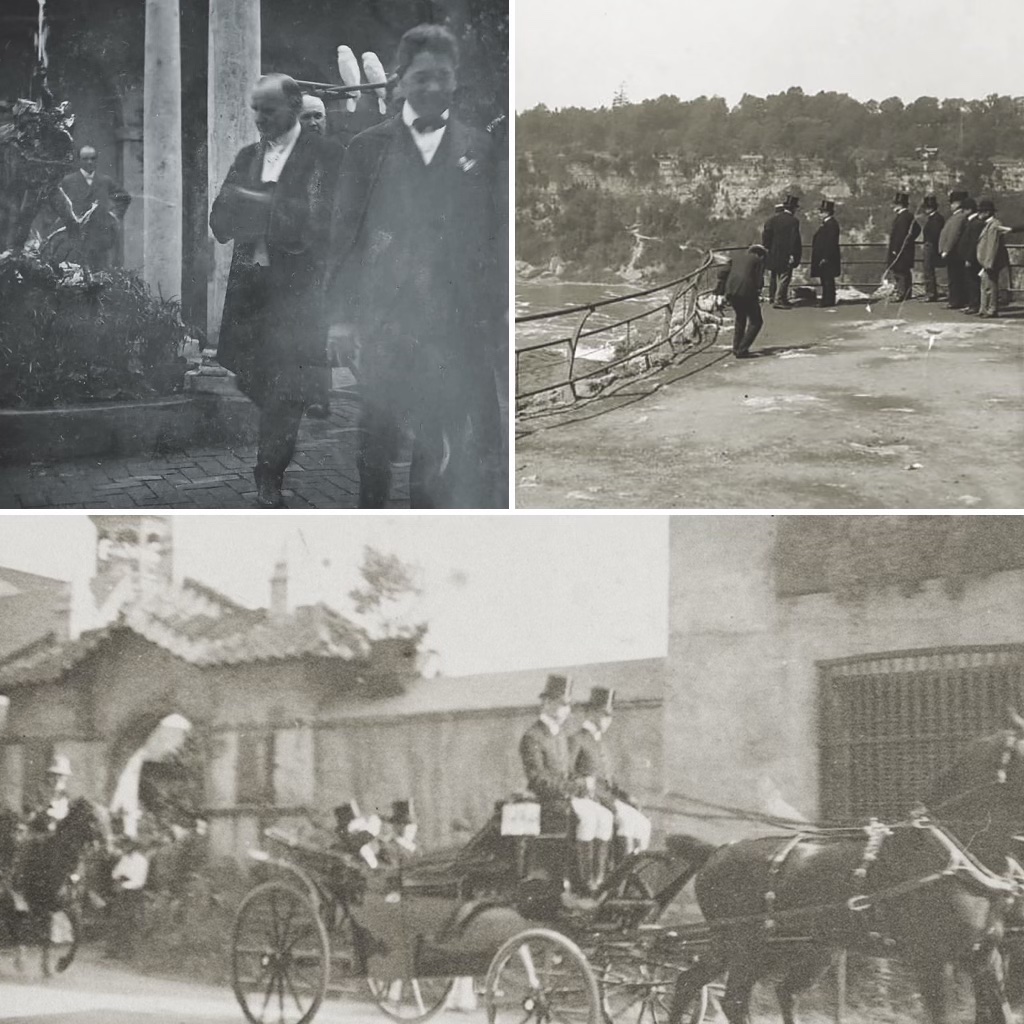

Gilbert D. Brinckerhoff, capitalizing on opportunities created by the Pan American Exposition, was running a chain of souvenir and photography stands on the fairgrounds. He had taken the day off from overseeing his operation to bring his camera on the McKinleys’ Niagara Falls excursion. He got the first picture of the president at the falls, an image of McKinley stoically staring into the lens from a Great Gorge Route railcar.

Orrin E. Dunlap also had brought a camera to the falls. A writer, historian, and newspaperman who had edited the Niagara Gazette from 1890 to 1895, Dunlap had written extensively on the Falls and electrification. An enthusiast with serious journalistic experience behind the lens, Dunlap made six exposures of McKinley, three of the president with Milburn touring the park adjoining the falls, one as the president was climbing stairs at Goat Island—a moment also captured by Niagara Falls stationer George S. Cowper—and two in sequence at Prospect Point.

The last frame documented Robert Dunn documenting a conversation involving the President, Exposition president Milburn, and Thomas V. Welch, the first Superintendent of the New York State Reservation at Niagara Falls.

While he and his companions were wandering Goat Island, President McKinley requested that a photo be taken. “Quick as a flash it was taken by Mr. Dunn of ‘Leslie’s Weekly,’ before the word was scarcely uttered,” National magazine wrote later. The picture shows Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson, President McKinley, and John Milburn posing together, as in the background Secret Service man George Foster hovers, peering into the lens.

When the presidential entourage repaired to the International Hotel for a luncheon, Niagara Falls-based photographer Thomas Smith made three photographs of McKinley. The tour resumed with a circumnavigation of the new Adams Power Station, in which vicinity Dr. William H. Potter, a Niagara Falls dentist, made two photographs of the President and Milburn seated in a carriage at the stone entryway to the power station.

Around 2:45 p.m. the president headed for the train to get to his reception at the Temple of Music but once on the Exposition grounds made a surprise detour to attend a tea at the Old Spanish Mission. Buffalo entrepreneur and exposition board member George K. Birge had invited the President to see the Mission, taking care to get word to White House photographer Johnston to be present with her camera. At the tea, where the President had just enough time to smoke a cigar, Johnston made several pictures. “I never saw him so genial and expansive,” she said. “Miss Johnston caught the party fair and square with her kodak showing the president as he removed his hat to bow and smile in his own gracious and charming manner,” the Rochester Democrat reported later.

After tea, as the entourage was departing, C.J. Waddell, a banker and amateur photographer from Albany, made a picture of the president and company with the Mission building as a backdrop. Hoping for a frame of the President on the move, Jimmy Hare had installed himself at the Temple near the spot where the presidential party was to arrive. So had a mob of onlookers. To kill time, Hare photographed the crowd drawn by a chance to press presidential flesh. McKinley was stepping from the carriage when Hare caught him at mid-stride, smiling. Hare remained outside. “Jimmy did not go into the building himself,” biographer Cecil Carnes wrote. “He paid a visit instead to his friend C.D. Arnold, official photographer of the exposition. The two men were chatting when a hurried little procession went by them bearing the president on an improvised stretcher. Horrified they heard the news.”

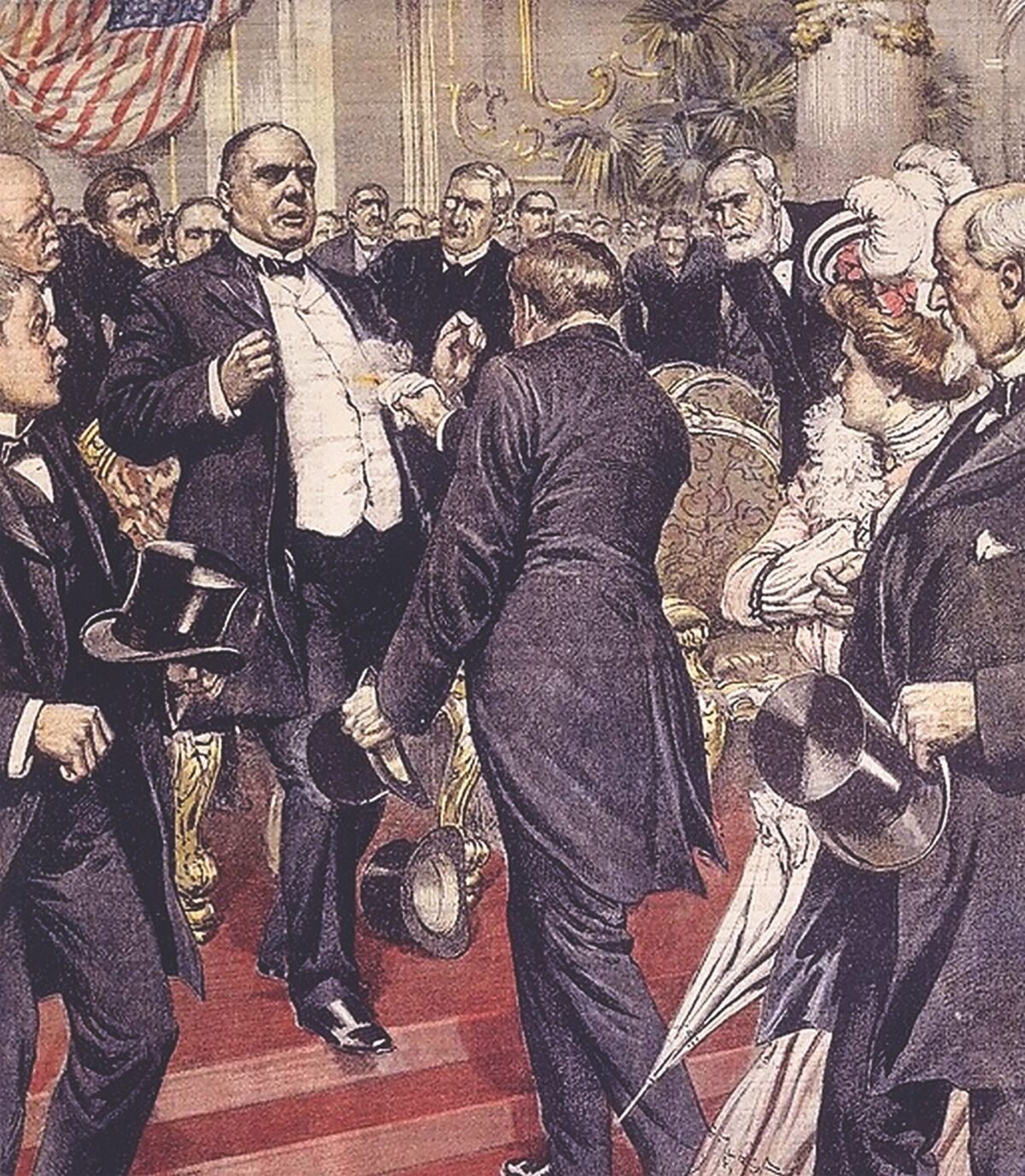

The news was that a fellow in line had shot the president at close range. Eyewitnesses described how “a well-knit young man, whose right hand, with seeming innocence, was in his back pocket. That hand held a pistol, and both were concealed from even the treacherous depths of the pocket by a dirty rag.” With his Iver Johnson hidden in a handkerchief Leon Czolgosz had waited his turn. As the President was offering his right hand, Czolgosz pulled his revolver and fired twice. The .32-calibre slugs tore into McKinley’s midriff.

“The smile, with its dimpled placid sunniness, left his face,” wrote journalist and eyewitness Richard Barry. James Parker, a waiter also in line, helped tackle the gunman. Secret Service man George Foster joined in the affray. Parker or Foster broke Czolgosz’s nose. A small electric ambulance rushed the wounded president to the Exposition’s emergency hospital. Expo photographer C.D. Arnold happened to be at that facility. He photographed the scene unfolding as doctors worked to stabilize their patient. Within days the president, recuperating at the Milburn residence, was said to be on the road to a full recovery. On September 14, 1901, he died.

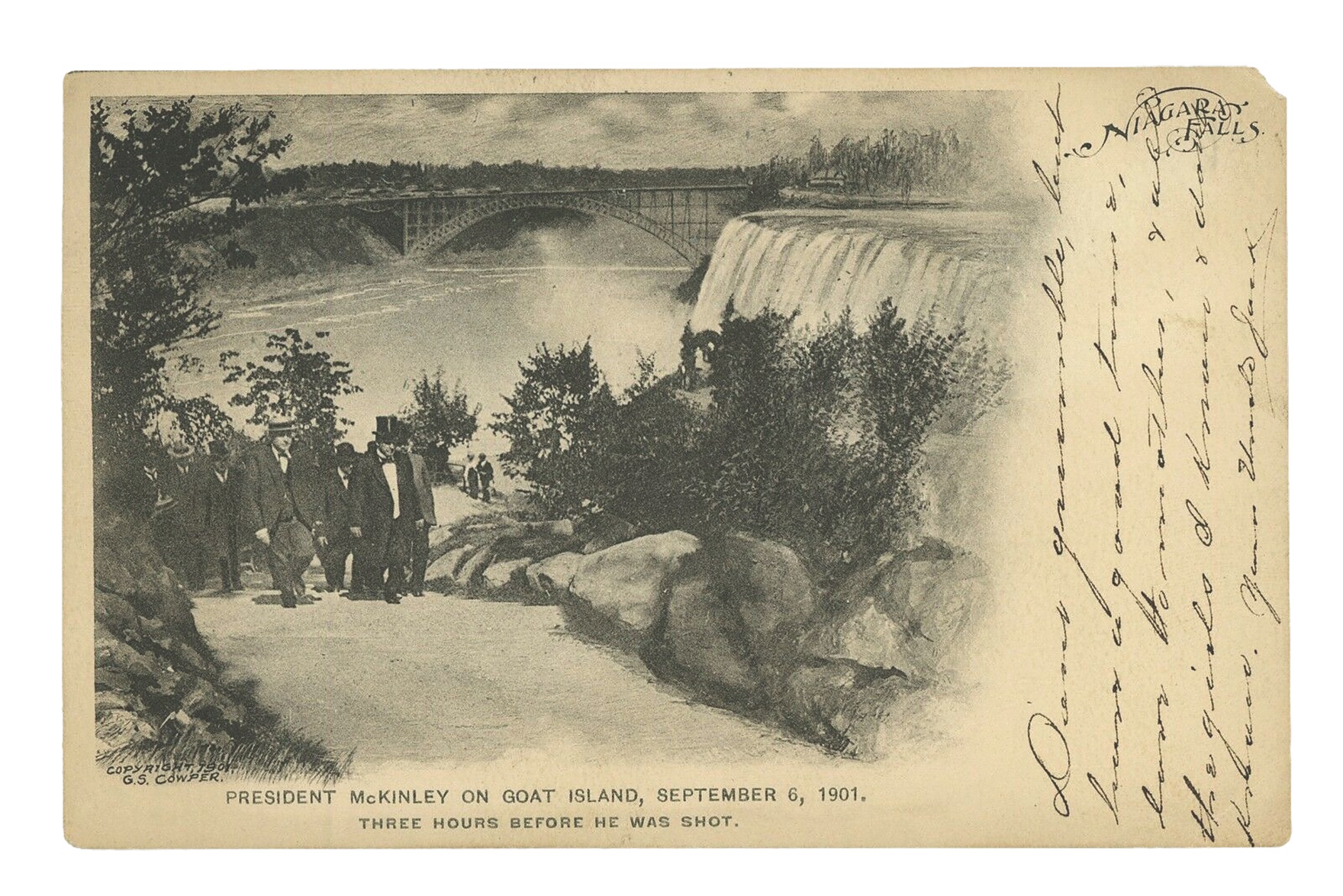

By then the race had long since begun to get images of McKinley into print. Hermann Brunn sold his photo, taken the day of the shooting, for $10 to the Buffalo Express; it ran in Sunday’s paper, and in the next three weeks Brunn sold 1,400 prints in and around Buffalo. Gilbert Brinckerhoff’s photo of McKinley looking into the lens from aboard his railcar ran in the weekly Western Electrician. “This photograph was made about four hours before the shooting on the exposition grounds and is possibly the last picture made of President McKinley in health,” the caption read. Stationer Cecil Cowper, responsible for one of two pictures of the president on the Goat Island staircase, printed a postcard of his photograph that he sold in packets of 12 for 25¢, touting the image as being “of historic value and it was about the last photograph taken of our Late President.”

Robert Dunn’s photo of McKinley, Milburn, and Welch on Goat Island appeared in the front matter of Murat Halsted’s 1901 book The Illustrious Life of William McKinley, captioned “Last Photograph of McKinley, The Day He Was Shot.” Thomas Smith, who had been at the hotel luncheon, filed his three photos for copyright under the description “The Last Photograph of William McKinley No. 1, 2, and 3.” The National Museum of American History in Washington, DC, displays one of Dr. William Potter’s photographs from the power station bearing the description “As nearly as can be determined, the above photograph is the last picture ever taken of President William McKinley.” Frances Benjamin Johnston’s “Last Photograph,” of McKinley leaving the Old Mission tea party, proved so popular George Eastman considered undertaking an advertising campaign based on the fact that Johnston had been using a Kodak. One of C.D. Arnold’s images from the chaos at the emergency hospital frequently is reprinted with the claim that a stretcher-bound McKinley is somewhere in the frame—though the optimistic caption never labels Arnold’s photograph as the last one of the president.

The British Journal of Photography in 1904 stated that Jimmy Hare, “in picturing Mr. McKinley as he mounted the steps of the Temple of Music, took the last photograph of the living President.”