The 1908 murder of Pat Garrett in New Mexico Territory’s Doña Ana County remains one of the West’s persisting whodunits. Broach the subject at any gathering of Western history aficionados, and you’ll start a lively, lengthy debate. The numerous publications bearing on the topic differ in important details of the narrative. The matter is further complicated by the reluctance of primary sources to have revealed all they knew when interviewed, misinformation that originated with attorney Albert B. Fall, and a lack of evidence to establish motive, means and opportunity beyond a reasonable doubt.

Fueling the debate are more than 16 books and scores of articles and archived documents, not to mention countless other sources deemed unacceptable by most scholars. As the case has been legally settled since May 4, 1909, and all players in the drama have long since headed for the last roundup, whatever conclusion researchers draw must be based on a preponderance of existing evidence, the standard imposed on juries in present-day civil cases.

The Facts

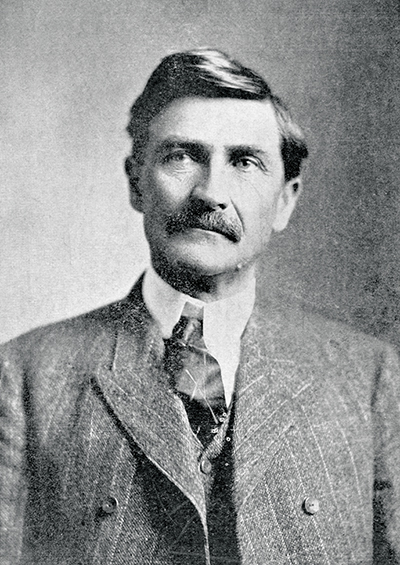

Following are the verified facts of the case. The victim, Patrick Floyd Jarvis “Pat” Garrett, was the former sheriff of Lincoln County best known for having killed outlaw Billy the Kid on July 14, 1881. Garrett served as sheriff of Doña Ana County from 1896 to 1900.

He was murdered at about 10:30 on the morning of Feb. 29, 1908, some 5 miles east of Las Cruces. His killer first shot Garrett in the back of the head, then shot him again in the abdomen as he lay dying. Garrett had been headed to town ostensibly to finalize the sale of his ranch in Bear Canyon on the eastern slope of the mountains just north of Agustín Pass.

He’d been riding in a rented two-horse buggy driven by Carl Adamson, one of the “buyers,” and accompanied by Wayne Brazel on horseback. Brazel had a lease on the ranch, was grazing goats on it and disputed Garrett’s termination rights. The route the men took from the Organs down to Las Cruces (a descent of 1,184 feet) was the Mail-Scott Road, a wagon track that ran just over a dozen miles through Alameda Arroyo.

At a point some 5 miles northeast of Las Cruces a smaller arroyo runs into the south side of Alameda. A wagon track through the smaller arroyo trended southeast from the junction across rangeland controlled by influential local rancher William W. “Bill” Cox. Existing accounts neglect to mention that key geographic feature of the murder site.

A Confession

Around noon that day in Las Cruces, Doña Ana County Deputy Sheriff Felipe Lucero (his brother José R. Lucero was sheriff) was preparing lunch when Brazel burst into the office and exclaimed: “Lock me up! I’ve just killed Pat Garrett!”

Adamson accompanied Brazel into the sheriff’s office, handed over Brazel’s revolver and, as the sole eyewitness, gave Lucero his account of the killing. He related a tale of self-defense, which seemed dubious, as Garrett was shot in the back of the head while standing beside the buggy in the midst of urinating, one glove off and no weapon in hand. But never mind—his killer had confessed.

Brazel was indicted on April 13, 1908, and tried on May 4, 1909. Although Adamson was not subpoenaed and did not testify, his account of the killing to the grand jury was in evidence.

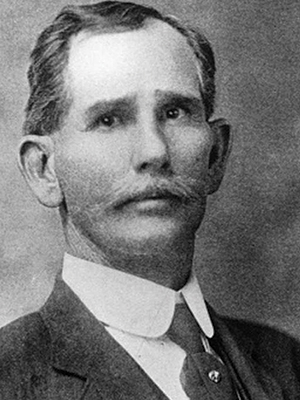

Defending Brazel was attorney Fall, a ruthless politician and consigliere for the W.W. Cox/Oliver Lee political mafia of Doña Ana County. As witnesses, Fall called policeman John Beal, saloonkeeper Jeff Ake and rancher Jim Baird, each of whom testified Garrett had threatened Brazel’s life. The prosecutor was District Attorney Mark Thompson, a longtime Fall associate, who centered his case on Adamson’s eyewitness account. Nothing was mentioned about the latter’s conspicuous absence during the trial. The jury was out 15 minutes and returned a verdict of not guilty. That evening Cox hosted a celebratory barbecue at his ranch.

The Usual Suspects

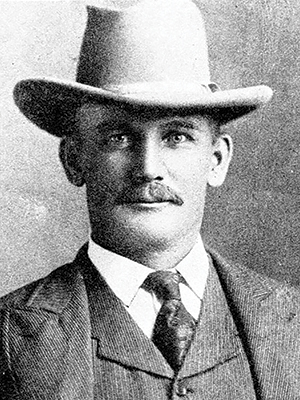

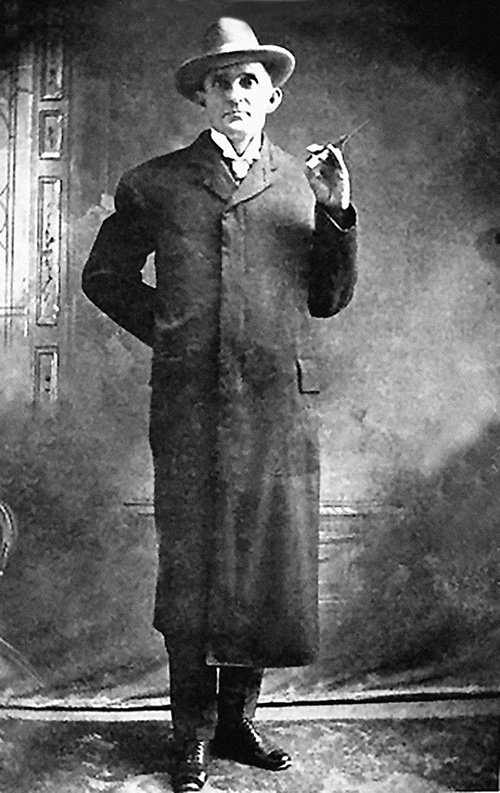

The usual suspects in the Garrett case are Cox, his brother-in-law Archie Prentice “Print” Rhode, Adamson, Brazel and notorious hired killer James Brown Miller (aka “Deacon Jim” or “Killin’ Jim”). The accepted narrative dismisses Miller as the primary murder suspect in favor of Brazel, due to the latter’s confession. As the backstory goes, Garrett, in desperate financial straits, was seeking to sell his Bear Canyon ranch to Adamson, who said he and his partner—one “James P. Miller”—owned a ranch in Oklahoma.

It seems reckless for Adamson to have invented a name for a fictitious partner that differs from known assassin Miller’s name by only the middle initial (using a “P” instead of a “B”). But contemporary journalists seemingly never wondered about the name. Adamson’s imaginary partner was said to have been waiting in El Paso during the ranch negotiations. Some versions of the story state James P. Miller never attended any of the meetings with Garrett.

Adamson claimed that on February 29 he and Garrett were traveling from the latter’s home ranch on the eastern slope of the mountains just north of San Agustín Pass to meet with James P. Miller and an attorney in Las Cruces, about 4 hours west by buggy. There they would work out a deal and draw up necessary papers for the sale. Brazel, who opposed the sale, rode alongside on his own horse.

According to Adamson, Garrett and Brazel argued heatedly en route. When Adamson pulled off the road for a rest stop, the argument reached the boiling point, and Wayne shot Pat twice with his revolver, allegedly as the latter reached for a gun, despite his compromising position.

First Degree Murder

Garrett’s body was recovered and brought into Las Cruces. Dr. W.C. Field, who performed the autopsy, found only the bullet that had struck Garrett in the abdomen, the other having passed through the victim’s head. Field described it as a .45 slug, though it could have been the nearly identical .44–40 Winchester bullet, which fits either a Colt revolver or a Winchester rifle. Dr. Field’s stated opinion was that Pat had been killed in cold blood—murder in the first degree.

Governor George Curry instructed New Mexico Territory Attorney General James M. Hervey and Captain Fred Fornoff of the Territorial Mounted Police to conduct an independent investigation of Garrett’s murder.

The pair interviewed Adamson, and on examining the murder site on March 5, 1908—the day of Garrett’s funeral—each found one freshly fired Winchester .44–40 shell. They concluded Adamson’s story didn’t make sense.

Governor Curry agreed, and though there were no funds to launch a deeper investigation, he told Hervey and Fornoff to do what they could.

Each made inquiries in El Paso. Hervey tried unsuccessfully to raise money for the investigation from Garrett’s longtime friend Tom Powers (a partner in the Coney Island Saloon). He also solicited Pat’s friend author Emerson Hough in Chicago, who begged off and cautioned Hervey to drop the investigation or “get killed trying to find out who killed Garrett.”

Meanwhile, Fornoff got wind of a reported autumn 1907 meeting between conspirators and Jim Miller at El Paso’s St. Regis Hotel. Fornoff supposedly wrote up the details for Hervey, though his report has since disappeared.

Word had it Garrett’s friends in Las Cruces overwhelmingly believed Miller was the assassin, though few would publicly state that belief, as they feared the powerful Cox/Lee/Fall faction. In 1970 El Paso author Leon C. Metz interviewed 93-year-old Frank C. Brito, who had served as a Rough Rider under Theodore Roosevelt, a deputy sheriff of Doña Ana County and the jailer at Las Cruces for 20 years under the Lucero brothers.

“I don’t like to talk about Pat Garrett,” Brito told Metz. “He was a friend of mine, and that’s all I have to say.”

Period newspaper accounts suggest officials ultimately accepted Adamson’s story as the truth. There is no indication anyone knew Adamson and Miller were brothers-in-law.

“Killin’ Jim” Miller of Soledad canyon

John P. Meadows was living in Tularosa, Otero County, about 80 miles northeast of Las Cruces, when Garrett was slain. He’d been a friend of Pat’s since about 1880 and had served under him as a Doña Ana County deputy during the investigation into the February 1896 disappearance and probable double murder of attorney Albert Fountain and son Henry. Fountain had run afoul of the Cox/Lee/Fall cabal. But the prevailing power brokers in Las Cruces and Doña Ana County didn’t intimidate Meadows. Some of what he knew about the Garrett murder came from sources independent of the rumor mill in Las Cruces.

On June 13, 1936, 10 days before Meadows died, historian J. Evetts Haley interviewed him in Alamogordo, N.M. A transcript of that interview resides in the Nita Haley Stewart Memorial Library at Midland, Texas. Y

et none of the existing books and articles about Garrett reference the Meadows interview, a document that seems relevant for several reasons: 1) Meadows knew Garrett well personally and professionally; 2) Meadows lived in Tularosa throughout Garrett’s stint in Las Cruces and was his deputy during the related Fountain murder investigation and trial; 3) Meadows was considered a reliable source; 4) his story contains information found nowhere else; and 5) it provides new information about the murder.

Such a scenario fits the facts. It wasn’t Wayne Brazel who did the dirty deed. It was Killin’ Jim Miller by way of Soledad Canyon.

Meadows told Haley that on Feb. 26, 1908, Adamson had visited Jim Baird’s ranch, west of White Sands, and the next day Miller had ridden south through Tularosa. According to Meadows, on February 28, a young cowboy who worked for rancher W.N. Fleck told sometime-cowboy and retired Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo he’d seen Miller ride by Fleck’s spread, “down here 20 miles this side of El Paso, riding a big gray horse branded S bar,” adding, “Jim Beard [sic] here owned that horse. He was fresh shod.”

Meadows’ details mesh with facts from other sources: 1) Baird, a Cox associate, owned a ranch where Meadows claimed; 2) Fleck owned a ranch about 20 miles north of El Paso, crossed by the El Paso & Southwestern Railroad tracks (present-day U.S. 54); 3) Adamson, Miller’s brother-in-law, was definitely in the Tularosa Basin/Las Cruces area.

Assassinated?

Meadows then told Haley of two black men from Tularosa who had been traveling behind the Garrett party and were also headed for Las Cruces. The pair said they’d heard the shots and decided it best to pause their journey. When they did continue, they came on the murder scene and noticed horse tracks leading from Garrett’s body into an arroyo about 50 yards to the south. The men said it looked as though a horse had been waiting in that arroyo all night.

According to Meadows, Eugene Van Patten—a former sheriff of Doña Ana County and respected pillar of the community—had examined the site on the afternoon of Garrett’s murder and told Meadows of similar findings, adding the horse had dunged four times, suggesting it had waited in the arroyo overnight.

In considering the Meadows interview, I focused on clues to the killer’s identity, how he may have traveled to and from the murder site, and information bearing on the logistics of such an undertaking. I did not consider Meadows’ account about Miller traveling down through Tularosa, as that is not critical to the murder narrative.

Assuming Miller was the assassin, whatever he did would have to be consistent with the hard facts of the case. Such considerations led to the following interpretation of Meadows’ tale.

Miller was well known by reputation, and it is likely at least some New Mexico Territory lawmen had seen photos of him, so any plan had to steer Miller away from Las Cruces. Statements in newspapers and books to the effect Miller was “seen in Las Cruces” on the day of Garrett’s murder were unattributed, implying they were hearsay or whole-cloth fiction. Either way, they lack credibility. Adamson’s presence was risky enough.

Conspiracy to Murder

District Attorney Thompson subpoenaed a batch of Western Union telegrams exchanged by Adamson, Cox, Rhode, Brazel and Miller a day or two before the murder, yet he didn’t place them in evidence at Brazel’s trial. Such an omission seems tantamount to conspiracy to murder, as the telegrams may have been sent to arrange Miller’s journey to and from the murder site, conceivably tying him to the plot.

The sighting of Miller on a distinctive horse owned by rancher Baird the day before the murder at a point on the Fleck ranch some 20 miles north of El Paso suggests a route by which Miller could have approached the murder site, done the job and slipped away unseen. He could have taken a northbound morning train from El Paso on February 28 to a prearranged spot on the EP&SW tracks, debarked, met Baird, mounted the saddled and provisioned horse, and made the three-hour ride through Soledad Canyon to the murder site. A well-kept secret among 19th-century ranchers, Soledad is the only canyon that crosses the Organ range.

Once through, Miller could have met Adamson as the latter drove out to Garrett’s place, and together they could have chosen the spot where Adamson would stop the buggy the next morning. Then Miller could have tied the horse to a bush in the feeder arroyo and camped for the night.

Had everything played out as planned, at 10:30 the next morning Miller would have been in his selected shooting spot, made the kill with two shots from a Winchester .44–40 rifle (chosen for the range to his target) and retraced his route to the EP&SW tracks. There he would have turned the horse over to a waiting accomplice and flagged down the southbound afternoon passenger train to El Paso. He would have been back at his hotel by evening.

Such a scenario is consistent with Meadows’ story. It is also consistent with the need for coordination by telegraph, the discovery of two spent .44–40 shells at the murder site, the horse tracks leading back into the feeder arroyo and the amassed dung.

The Fountain Murders

Back in 1896, when Doña Ana County officials had refused to look into the suspected double murder of Albert Fountain and his 8-year-old son, Henry, at Chalk Hill in the Tularosa Basin, territorial officials had brought in Garrett from Uvalde, Texas, to Las Cruces to investigate.

His presence was met with resentment by the existing power structure, a faction dominated by the very people who were likely suspects. When Garrett’s subsequent murder case against Oliver Lee and Jim Gililland ended in acquittal in June 1899, they and their associates hoped Garrett would move on and leave the Las Cruces area. But it was not to be.

From the time Garrett filed for a homestead on his ranch near W.W. Cox in 1899, it was apparent to all the Tularosa Basin ranchers who had been suspected of involvement in the Fountain murders that Pat was sticking around and might well be thinking of the $10,000 reward offered by the Masonic Grand Lodge of New Mexico Territory for the arrest and conviction of the murderers. The ranchers’ lawyer and consigliere, Albert Fall, continued to advise them while making life as miserable as possible for Garrett, spreading false stories that maligned him as a dangerous bully. By fall 1907 such efforts had obviously failed to dislodge him, and the ranchers reportedly began to contemplate murder.

According to the sources interviewed by Territorial Mounted Police Captain Fornoff, the desperate conspirators scheduled a secret meeting that fall at El Paso’s St. Regis Hotel to plan Garrett’s assassination. Among those reportedly in attendance were Cox, Lee, Fall, Rhode, Miller, Adamson and Emmanuel “Mannie” Clements Jr. (another of Miller’s brothers-in-law). After agreeing on a fee, the ranchers reportedly hired Miller to kill their common enemy, Garrett.

The rest of the meeting concerned how to pull off the murder. Miller insisted on taking no chances he would be suspected of involvement, let alone arrested. His employers would not only have to lure Garrett to a suitably remote site, but also provide a willing “shooter” to take the blame and an “eyewitness” to relate a credible account of the killing, a case of self-defense Fall might easily defend in court.

The Most Likely Scenario

An offer to purchase Garrett’s ranch would serve as a lure to secure the victim’s cooperation. The ranchers could recruit Garrett’s disaffected lessee, Brazel, to be the faux shooter, while the actual assassin, Miller, would travel to and from the secluded site by an improbable route. Such were feasible solutions, but they would require management and coordination in an age of limited communication channels—telephones in towns, telegraph service to more remote areas. Moreover, Miller must not be seen in Las Cruces during his approach or retreat.

The conspirators reportedly solved all the issues. Cox would recruit Brazel, while Adamson would lure in Garrett and orchestrate the operation, contacting Miller in El Paso by telephone or telegram as appropriate. Cox, Lee and Baird would plan Miller’s route.

Sometime in January or early February 1908 Miller reportedly arrived in El Paso to address any remaining issues and study the planned approach and retreat. The chosen route would lead through Soledad Canyon, marked by Soledad Peak, visible to the northwest from the El Paso & Southwestern Railroad tracks.

The little-traveled gorge wove an easy 10-mile track through the Organ Mountains. At the west end of the canyon the route turned northwest along a wagon track that dropped into the smaller arroyo and emptied into Alameda Arroyo about 5 miles east of Las Cruces. Where the arroyos met would be the designated kill site. The overall route from the railroad ran about 32 miles, easily traversed in about three hours on a trotting horse. Tellingly, the entire route lay on open rangeland controlled by W.W. Cox or his friends and associates.

Such a scenario fits the facts. It wasn’t Wayne Brazel who did the dirty deed. It was Killin’ Jim Miller by way of Soledad Canyon. That said, doubtless the debate will continue.

Western history author-researcher Jerry Lobdill earned the Wild West History Association’s Six-Shooter Award for best general Western article for the above feature, which was published in the August 2018 Wild West. Lobdill thanks the late Cal Traylor (onetime president of the Doña Ana Historical Society and Friends of Pat Garrett), Frank H. Parrish, Bob Gamboa and Becky Campbell for consultations on Garrett’s murder. For further reading he suggests Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, by Leon C. Metz; The Fabulous Frontier, by William A. Keleher; Tularosa: Last of the Frontier West, by C.L. Sonnichsen; and Sheriff Pat Garrett’s Last Days, by Colin Rickards.