Pat Garrett admitted dreading only one thing, and it had nothing to do with facing down a killer.

Instead, it was facing a stranger who, on being introduced to the lawman, would exclaim: “Pat Garrett! The man who shot Billy the Kid, the noted desperado! Glad to meet you! When I write home, I shall say that I actually had the honor of shaking hands with you” — or something similar.

A soft-spoken and modest man, Garrett abhorred such encounters. “I sometimes wish that I had missed fire, and that the Kid had got his work in on me,” he lamented to a friend.

Garrett’s feat of single-handedly killing one of the West’s most notorious outlaws had been a double-edged sword. It had given him instant celebrity, a cash bonanza via a reward and donations from grateful citizens, and entrée to prominent politicians and businessmen. But the dead outlaw’s growing legend also haunted Garrett. Kid sympathizers branded Garrett a coward for shooting down Billy in the dark and claimed the Kid was unarmed to boot. And in Garrett’s later years, many viewed him as a violence-prone relic from an unseemly past.

Pat Garrett deserved better. The man had his flaws, but he was a sure enough hero when New Mexico needed one, and he rates in retrospect as one of the West’s greatest lawmen.

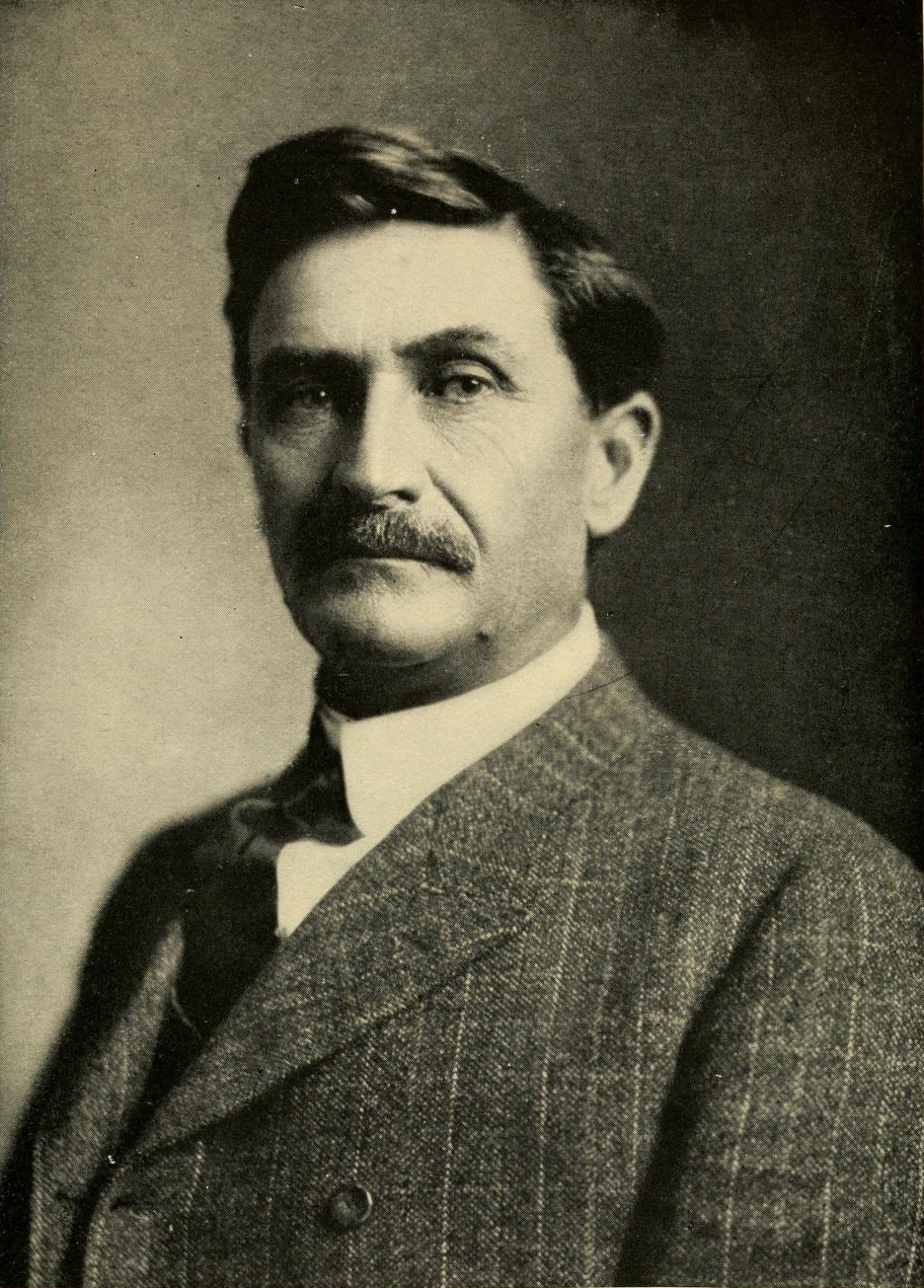

Born in Chambers County, Ala., on June 5, 1850, Patrick Floyd Garrett moved with his family to a Louisiana cotton plantation when he was 3 years old. He enjoyed a relatively privileged upbringing, earning his first dollar working in his father’s plantation store. But the Civil War changed all that. Losing his slave labor and seeing his crops confiscated, Pat’s father sank deep into debt and alcoholism, dying a broken man in 1868. Upset at the handling of his father’s estate, 18-year-old Pat struck out for Texas on January 25, 1869.

Garrett farmed for a couple of years around Lancaster (south of Dallas) but gave it up to become a cowpuncher. By 1876, he had switched occupations again, joining the hunters and skinners who were fast eradicating the bison herds on northwest Texas’ Staked Plains. His hide business partner, Willis Skelton Glenn, remembered Garrett as “rather young looking for all of his 25 or 26 years, and he seemed the tallest, most long-legged specimen I ever saw.” Garrett stood a remarkable 6 feet 4 inches in his stockings.

“There was something very attractive and impressive about his personality,” Glenn recalled, “even on a first meeting.”

It was on the buffalo plains that Garrett killed his first man, but that man was no outlaw or bully. He was a young friend of Garrett’s named Joe Briscoe. A silly tiff between the two quickly escalated into blows, and when an enraged Briscoe came at Garrett with the cook’s ax, Garrett grabbed the camp pistol and pulled the trigger at point-blank range. As Briscoe lay dying, he asked his killer’s forgiveness. A distraught Garrett turned himself in at Fort Griffin, but the law there had no interest in pressing charges against him. All they had to go on was Garrett’s story, and the evidence — Briscoe’s body — was buried miles away under a clump of mesquite.

Garrett settles in New mexico

With hunters like Garrett, who could kill 60 or more buffalo a day, it did not take long for the Texas hide men to put themselves out of business. Garrett and two companions drifted into New Mexico Territory, arriving at the small settlement of Fort Sumner on a cold February day in 1878. Garrett’s pals soon moved on, but Garrett made Fort Sumner home, the locals nicknaming him Juan Largo (“Long John”). He tried various business endeavors: hog farm, butcher shop and combination saloon and grocery. And he married two local gals. The first, Juanita Martínez, fell sick with a mysterious illness on their wedding night. She died the next day. His second wife, Apolinaria Gutiérrez, whom he married in January 1880, would eventually bear him eight children.

Fort Sumner was where Garrett first encountered Billy the Kid, who found the settlement’s watering holes, young ladies and weekly bailes as attractive as had Garrett before him. Nearly 10 years Billy’s senior, Garrett might find himself across a poker table from the Kid, but the two were neither chums nor enemies.

“He minds his business, and I attend to mine,” Garrett once told a friend when asked about Billy. “He visits my wife’s folks sometimes [the Kid was friendly with the Gutiérrez family], but he never comes around me. I just simply don’t want anything to do with him, and he knows it, and knows that he has nothing to fear from me as long as he does not interfere with me or my affairs.”

Once Garrett was elected sheriff of Lincoln County in November 1880, his business became Billy the Kid and his gang of stock rustlers. Why Garrett ran for sheriff and, more significant, why Roswell cattleman and business entrepreneur Joseph C. Lea handpicked the lanky former buffalo hunter for the job are unknown. But in hindsight, Lea’s assessment of Garrett as the right man to put a stop to New Mexico Territory’s most wily, if not most dangerous, outlaw was a stroke of genius. Smart, determined and brave, Garrett would take to the job as if born to it, quickly proving himself an unparalleled manhunter.

billy’s capture — and shooting

Garrett wasted no time in going after the Kid; he actually started his pursuit weeks before his official term as county sheriff began, having received appointments as a deputy sheriff and deputy U.S. marshal. In the midst of a memorably harsh winter, Garrett led posses all over eastern New Mexico Territory. Through sharp cunning, he ambushed the Kid and his pals at Fort Sumner, fatally wounding Billy’s close friend Tom Folliard when Folliard ignored Garrett’s command to throw up his hands and instead went for his gun. Billy and the rest of the gang escaped into the darkness. Four days later, in the early morning hours of December 23, Garrett and his posse tracked Billy and cohorts Charlie Bowdre, Dave Rudabaugh, Billy Wilson and Tom Pickett to an abandoned stone house northeast of Fort Sumner at Stinking Spring (present-day Taiban).

Billy, who had helped gun down a former Lincoln County sheriff and deputy during the Lincoln County War, had let it be known he would never be taken alive, so Garrett instructed his men to shoot to kill if Billy appeared outside the house. Unfortunately, Bowdre stepped through the doorway at first light wearing garb similar to Billy’s, and Garrett and his men let him have it. Bowdre lived only a few minutes. A siege of several hours ended when Billy and the gang surrendered after Garrett gave his word he would protect them from any lynch-happy New Mexicans.

Giving one’s word was no small thing to Garrett, and in one of the lawman’s finest moments, he and a handful of men stood off an angry mob at the Las Vegas, N.M., train station bent on lynching Rudabaugh for a previous murder. The armed crowd even had local law officers on its side, but Garrett made them back down, too. Garrett was so determined to keep his pledge that he told Billy and the others he would give them their guns if the mob attacked their Pullman. Garrett and his men were able to get the train out of Las Vegas before it came to that, but if there was ever any question as to Garrett’s grit, that episode put it to rest.

A fact often overlooked when assessing Garrett’s career is that he had to hunt down the Kid not once, but twice. After a Mesilla court convicted Billy for the murder of Sheriff William Brady, it placed him in Garrett’s care to await the date of his hanging. But in what would become the most infamous jailbreak in Western history, Billy killed his two guards and fled the town of Lincoln while Garrett was in White Oaks collecting county taxes. Garrett bided his time for weeks until he received good information the Kid was hanging around Fort Sumner to be close to a sweetheart, Paulita Maxwell. Garrett then slipped out of Lincoln with two deputies, and on the moonlit night of July 14, 1881, he shot his man dead in the darkened bedroom of Pete Maxwell (Paulita’s brother), a scene that has been reenacted time and again in movies and on television—and one that has been the source of some controversy. Over the years, various parties have questioned Garrett’s version of the shooting, some even making the bizarre claim that Billy didn’t really die that night.

Recommended for you

Garrett’s life After billy’s death

That fateful face-to-face confrontation birthed an American legend and came to define Garrett, so much so that few today realize or care that Garrett lived another 26 years, each one filled with highs and lows — and not a one uninteresting. Contemporary newspapers contain numerous references to Garrett and his exploits post-Billy. In June 1882, for example, the Las Cruces Rio Grande Republican reported that Sheriff Garrett and posse trailed an Indian raiding party 90 miles in an effort to recover 21 head of stolen horses. After a “fearful storm” wiped out all tracks, and with their provisions exhausted, Garrett was forced to turn back, but he did recover six of the animals (one or two had been lanced). There would be more manhunts in Garrett’s future.

Garrett declined to run for a second term as Lincoln County sheriff in order to run for the territorial council. He lost the election, after which he devoted his energies to ranching near Fort Stanton. In 1884, Garrett returned to chasing rustlers for a living when the Texas governor commissioned him a captain of an independent ranger company, his salary to be paid by the panhandle’s larger cattle operations. At the time, there was much tension between the big cattlemen and the small ranchers and cowboys. A recent gubernatorial proclamation prohibiting civilians from wearing six-shooters became a priority for Garrett, and according to his friend John Meadows, Texas “got Pat Garrett just in time to save another Lincoln County War, and Pat, he understood it, and he disarmed every doggone one of them.” Less than a year later, Garrett quit the ranger business when it became apparent his cattlemen employers preferred he kill the worst rustlers rather than bring them to justice.

In the late ’80s, Garrett masterminded and helped implement a plan to transform the Pecos Valley into a farmer’s paradise, with strategically placed dams, flumes and irrigation canals. His own farm at his home near Roswell became one of the most valuable in the valley. Garrett also invested in several local business ventures: a Roswell hotel, blacksmith shop, livery stables in Roswell and Eddy (present-day Carlsbad) and even a stage line. But Garrett was also running through a lot of money. When he and his partners were forced to bring in large capitalists to continue the irrigation project he had envisioned, Garrett, who could not match these substantial contributions, was forced out.

In 1890, when legislators carved Chaves County from Lincoln County, Garrett threw his hat in the ring to become the new county’s first sheriff. Because of his hard work and many investments in the Pecos Valley, he was an obvious frontrunner. But John W. Poe, Garrett’s former deputy and successor as Lincoln County sheriff, had fallen out with Garrett over a loan. Poe endorsed another candidate, which, along with something of a backlash over Garrett’s fame and popularity, cost Pat the election. Disgusted, Garrett moved his family to Uvalde, Texas. It appeared his days as a lawman of any kind might be over.

At Uvalde, Garrett again invested in irrigation, but he devoted most of his time to breeding and racing blooded trotters. Garrett had always been a gambling man, which had contributed greatly to his financial troubles over the years, and he and his horses became well-known fixtures at racetracks from Albuquerque to New Orleans. Yet his winnings did not come close to reducing his growing debt.

A return to law enforcement

Garrett’s fortunes took a turn for the better in February 1896, however, when New Mexico Territorial Governor William T. Thornton sent him an urgent communication. Someone had murdered prominent Las Cruces attorney and politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son near New Mexico’s White Sands, and Thornton wanted the Southwest’s most famous manhunter put on the trail of the killers, who had disappeared, as had the bodies of their victims.

It was a triumphant return to New Mexico for Garrett, who soon secured the job of Doña Ana County sheriff. The leading suspects in the Fountain murders were rancher Oliver Lee and associates William McNew and Jim Gililland. Less than two weeks before his murder, Fountain had obtained indictments against Lee and McNew for cattle theft and brand defacing. Garrett’s investigation took time, but in April 1898, he secured bench warrants in the murder case and promptly arrested McNew and another suspect. Lee and Gililland, on the other hand, made themselves scarce, refusing to turn themselves in to the lawman. Lee was Garrett’s match in cunning and marksmanship, and at a now-famous gun battle at Wildy Well, one of Lee’s satellite ranches in the Tularosa Basin, the two wanted men got the better of Garrett. From a commanding position on the roof of the ranch house, Lee and Gililland pinned down Garrett and his four deputies, mortally wounding one. When the shooting stopped, the fugitives agreed to let Garrett and his men retreat to a safe place, after which Lee and Gililland made their escape.

Garrett’s doggedness finally wore down the fugitives, however, who secretly arranged to turn themselves in to the district court judge in Las Cruces, thus bypassing the sheriff. Their subsequent trial, in May and June 1899, received national press coverage and quickly turned into a battle between Republicans and Democrats, big cattleman and small ranchers. Garrett shined on the witness stand, but Lee and Gililland were acquitted, due in large part to their brilliant attorney and local power broker, Albert Bacon Fall. No one was ever convicted of the murders of Fountain and his son. Garrett chose not to run again for Doña Ana County sheriff, although he had conducted the sheriff’s office better than any of his predecessors. He explained to a reporter in November 1900 that times had changed in the territory, and the sheriff’s office no longer needed his “peculiar talents in the line of good marksmanship and quick action at the head of posses.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

A year later, Garrett’s name was back in the national headlines when President Theodore Roosevelt chose Garrett for the post of El Paso customs collector. Roosevelt had appointed Garrett over the strong objections of Texas Republicans, who felt the plum job should go to a Texan — and one of their choosing, of course. But Garrett had a strong supporter in Lew Wallace, the former governor of New Mexico Territory, who visited the president to lobby for Garrett. Garrett later wrote his wife that Wallace had said, “He would do anything I asked him to do, says I did him a great favor once (in the ‘Kid’ affair), so he is anxious to express his gratitude.”

Garrett’s presidential appointment gave him a status and respectability he had not known as a county sheriff. Yet he retained his characteristic modesty.

“Pat never talked about how many men he killed,” recalled one El Paso acquaintance, “and it was the hardest thing in the world to get him to tell the story about his killing of Billy the Kid.” Indeed, Garrett never went “Buffalo Bill.” He did produce a biography of the Kid with friend and drinking companion Ash Upson, but Garrett saw that effort as his opportunity to answer falsehoods about his encounter with the Kid. And if he should make money on the venture (he didn’t), there were nickel novel publishers back east profiting off of his exploits, none of whom had looked down the barrel of the Kid’s Colt.

Garrett was also known as a dandy dresser in his later years, but never in frontier garb. His writer friend Emerson Hough once loaned Garrett a pair of souvenir Western leather gloves. Hough had been pleased with the gloves’ embroidery and long leather fringe, but the next thing he knew, Garrett had cut the fringe off.

“He was afraid of being thought Western,” Hough wrote, adding that Garrett “wore clothing which would have left him inconspicuous on Broadway.” In fact, on a trip to New York City on customs business, Garrett had asked a policeman directions to his hotel when the policeman, looking Garrett up and down, cautioned him to hold on tight to his bag. “There’s lots of fellows in this town looking for marks like you,” the policeman said.

In El Paso, Garrett performed his job as customs collector a little too well, causing complaints from those who thought they should have received some kind of break on their duties. Others complained about his gambling, drinking and absences from his post. What many believe finally cost Garrett a reappointment, though, occurred at an April 1905 Rough Riders reunion in San Antonio. Garrett had brought along his good friend Tom Powers, owner of the Coney Island drinking and gambling establishment in El Paso, and he arranged to have a photograph taken of himself and Powers with the president. When Roosevelt later learned he had posed beside a professional gambler and saloon owner, he was furious. Garrett traveled to Washington, D.C., in an attempt to save his position, but Roosevelt had made up his mind. After a four-year stint, Garrett was replaced with someone less controversial.

His collectorship gone, Garrett had little to rely upon for a steady income. His two small ranches in the San Augustin Mountains were hardly more than a hobby. Compounding difficulties was the fact Garrett could be generous to a fault. As one old-timer put it, “Anybody ask for anything, they got it.” It might be a milk cow, cash money or a signature on a banknote. This trait, combined with his investments in get-rich-quick schemes and an unabated passion for poker and horse racing, led to financial woes. Garrett became notorious for not paying bills and for owing money to friends. There were also rumors that Garrett was spending money on an El Paso prostitute known only as Mrs. Brown.

As Garrett struggled, he became bitter, angry, desperate and depressed.

“Everything seems to go wrong with me,” he wrote his friend Hough.

Pat Garrett dies in shooting

On February 29, 1908, Pat’s troubled life ended on a lonely stretch of road in Alameda Arroyo, a few miles east of Las Cruces. Cowpoke Wayne Brazel admitted to shooting Garrett, but said he had done so in self-defense as the two argued over a lease. Brazel claimed Garrett had reached for a shotgun. A witness, Carl Adamson, backed up Brazel’s story, but a Las Cruces doctor, after examining the crime scene and Garrett’s body, determined that Garrett had been shot in the back of the head while urinating beside the buggy in which Adamson and Garrett had been riding. Nevertheless, Brazel was later acquitted of murder. His attorney was none other than Albert Bacon Fall.

Garrett’s friends claimed he was the victim of a conspiracy, and to this day, questions remain on the circumstances of his death and whether Brazel was the actual triggerman. Many believe that notorious killer Jim Miller was hired to assassinate Garrett. This is likely true. Oliver Lee Jr., in a long-sequestered interview from 1954, claimed that his uncle, rancher W.W. Cox, had solicited Miller to do the deed. Cox was a neighbor (and major creditor) of Garrett’s, and he was said to be “deadly afraid” of Pat. But Lee also stated that someone else had beaten Miller to the job. Garrett’s murderer, Lee claimed, was Brazel’s friend Print Rhode, a known enemy of Garrett’s. Brazel took the blame, though, as Rhode had a family. Cox still had to pay Miller, Lee added, to buy the assassin’s silence. No matter who killed Garrett, it was a pitiful end for a Westerner who Billy the Kid biographer Walter Noble Burns called the “last great sheriff of the old frontier.”

In 1884, a Santa Fe newspaper predicted Garrett would “ever be held in grateful remembrance by the people of New Mexico for ridding the territory of a gang which has so long held it in terror.” Unfortunately, this has not been the case. Even within his own lifetime, Garrett began to see his popularity reversed with Billy the Kid’s. Americans famously celebrate their outlaw heroes while giving short shrift to the lawmen who risked their lives to bring those outlaws to justice. This year, however, Roswell is dedicating a bronze statue of Garrett by Texas sculptor Robert Summers. Incredibly, it is the first monument in New Mexico to the man who, it can be argued, brought law and order to the territory.

Right or wrong, Pat Garrett will always be the man who shot Billy the Kid and thus is safe from the tragedy that befalls many significant figures from our past who are forgotten with time. The real tragedy of Garrett’s legacy is that he was so much more, and we have forgotten that.

Historian Mark Lee Gardner wrote To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett and is now writing a book on the Northfield Raid. Visit www.markleegardner.com.

Originally published in the August 2011 issue of Wild West.