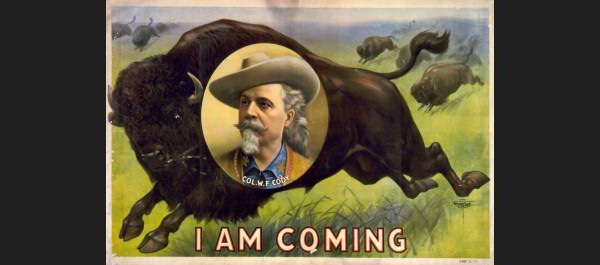

Buffalo Bill wanted an epic production with theatrical flair that defined the West and drew viewers into it.

When fabled bison hunter William “Buffalo Bill” Cody first staged his Wild West show in 1883, he needed more than heroic cowboys, villainous Indians, teeming horses and roaming buffalo to transform it from a circus into a sensation. He needed star power. And there was one man who guaranteed to provide it: the Sioux chief widely blamed for the uprising that overwhelmed George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn only a decade earlier. “I am going to try hard to get old Sitting Bull,” Cody said. “If we can manage to get him our ever lasting fortune is made.”

It took two years, but Cody finally got his man. In June 1885, Sitting Bull joined the Wild West show for a signing bonus of $125 and $50 a week—20 times more than Indians who served as policemen on reservations earned. Buffalo Bill reckoned his new star would prove to be an irresistible draw. With the Indian wars drawing to a close, and most Plains Indians confined to reservations, Buffalo Bill set the stage for a final conquest of the frontier. Since accompanying an army patrol as a scout shortly after the Battle of Little Bighorn and scalping the Cheyenne warrior Yellow Hair, he was known as the man who took “the first scalp for Custer.” As the man who now controlled Sitting Bull, he symbolically declared victory in the war for the West and signaled a new era of cooperation with the enemy. Cody excluded the chief from acts in which other Indians made sham attacks on settlers and then got their comeuppance from heroic cowboys. All Sitting Bull had to do was don a war costume, ride a horse into the arena and brave an audience that sometimes jeered and hissed.

Sitting Bull’s mere presence reinforced the reassuring message underlying Cody’s Wild West extravaganza, as well as the Western films and novels it inspired, that Americans are generous conquerors who attack only when provoked. At the same time, Cody’s vision of the West spoke to the fiercely competitive spirit of an American nation born in blood and defined by conflict on the frontier, where what mattered most was not whether you were right or wrong but whether you prevailed. The lesson of his Wild West was that sharpshooting American cowboys like Buffalo Bill could be as wild as the Indians they fought and match them blow for blow. The real frontier might be vanishing, but by preserving this wild domain imaginatively and reenacting the struggle for supremacy there, he gave millions of Americans the feeling they were up to any challenge.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West depended on Cody’s ability to draw shrewdly on his frontier experiences to make himself a commanding figure. He earned his nickname, he claimed, by killing 4,280 buffalo during an 18-month stint for the Kansas Pacific Railroad in the late 1860s. Indiscriminate hunting was encouraged by the army as part of a campaign to wipe out buffalo herds that gave subsistence to free-roaming Plains Indians. The Indians did not take well to having this food supply annihilated. Cody told of being chased once by 30 Indians on horseback. Cavalry guarding the tracks came to his aid, and together they killed eight “redskins,” he said, expressing sympathy only for a horse one of the warriors was riding, killed by a shot from his trusty rifle Lucretia: “He was a noble animal, and ought to have been engaged in better business.”

Later in life Cody mused that Indians deserved better. But his early exploits on the Plains and his autobiographical account of those feats, designed to portray him as a classic frontier enforcer, came first. His crowning claim involved the rescue of a white woman from the clutches of Indians. In July 1869, he was serving as a scout for the 5th Cavalry when it surprised hostile Cheyennes in an encampment at Summit Springs, Colorado Territory, where one white woman held captive was killed in the ensuing battle and one rescued. Official records give credit for locating the camp to Pawnee scouts—who volunteered to serve the army against their traditional tribal foes—and make no mention of Buffalo Bill. But Cody boasted of killing Cheyenne Chief Tall Bull during the engagement after creeping to a spot where he could “easily drop him from the saddle” without hitting his horse, a “gallant steed” he then captured and named Tall Bull in honor of the chief.

This fabricated tale demonstrated Cody’s knack for translating the grim realities of Indian fighting into rousing adventure stories in which he symbolically appropriated the totemic power of defeated warriors by claiming their scalp, horse or captives, much as Indians did in battle. But he took care to distinguish his bravery from the bravado of warriors who refused to fight fair and targeted women and children. Left unmentioned in his account of the Battle of Summit Springs—which, like the Battle of Little Bighorn, he incorporated as an act in his Wild West show—was that women and children were among the more than 70 Cheyennes killed or captured.

After returning with the cavalry from Summit Springs to Fort Sedgwick in Colorado, Buffalo Bill met Edward Judson, who was looking for Western heroes to celebrate in the dime novels he wrote under the name Ned Buntline. His fiction did so much to create and inflate the reputation of Buffalo Bill that actors were soon playing him on stage. “I was curious to see how I would look when represented by some one else,” Cody recalled, so while visiting New York in 1872 he attended a performance of Buffalo Bill: The King of the Border Men and was called on stage. He soon realized that he could succeed in the limelight simply by being himself, or by impersonating the heroic character contrived by Buntline.

“I’m not an actor—I’m a star,” he told an interviewer soon after making the transition from frontier scout to itinerant showman. Crucial to his ascent to stardom was his awareness that he needed to become something more than a stereotypical Indian fighter or “scourge of the red man.” He never renounced that role and continued to bank on it throughout his career, but his genius as an entertainer lay in softening his own image—and that of the Wild West—just enough to reassure Americans that the conquest he dramatized was a good clean fight that had redeeming social value without robbing this struggle for supremacy of its visceral appeal.

Buffalo Bill’s first appearance on stage in Chicago gave little hint of the bright future that awaited him in show business. He and other ornery frontiersmen blasted away at Indians ludicrously impersonated by white extras in a murky plot concocted by Buntline. One reviewer called the acting “execrable” and concluded that such “scalping, blood and thunder, is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city a second time, even Chicago.” Nonetheless, the show proved commercially successful, and Buffalo Bill made $6,000 over the winter, substantially improving his take in seasons to come by forming his own troupe called the Buffalo Bill Combination.

For several years, he combined acting with summer stints as a scout or guide, honing his skills as an entertainer by conducting wealthy dudes from the East and European nobility on hunting expeditions and diverting them with shows of skill that sometimes involved Indians hired for the occasion. Buffalo Bill enjoyed “trotting in the first class, with the very first men of the land,” and came away convinced that a Wild West spectacle involving real cowboys and Indians could appeal to all classes and become, as it was later billed, “America’s National Entertainment.”

Other showmen of the era tried to mine that same vein by mounting Wild West themed circuses in which sharpshooters and bronco-busters demonstrated their skills. But when Buffalo Bill launched his Wild West show in 1883, he set his aim higher. He wanted an epic production with theatrical flair that defined the West and drew viewers into it. After a lackluster first season, marred by his drunken escapades with a fellow sharpshooter and business associate named Doc Carver, he teamed with Nate Salsbury, a shrewd theater manager, and hired director Steele MacKaye to make the production more than a series of stunts by creating a show within the show called The Drama of Civilization. First staged in the winter of 1886 in New York’s Madison Square Garden, where it was viewed by more than a million people, the pageant was set against painted backdrops and included four acts that purported to represent the historical evolution of the West from “The Primeval Forest,” occupied only by wild Indians, to “The Prairie,” where civilization appeared with the arrival of wagon trains, setting the stage for further progress in the form of “The Cattle Ranch” and “The Mining Camp.”

The elaborate staging fulfilled Buffalo Bill’s stated goal of offering “high toned” entertainment, but the acts themselves suggested that the coming of the white man had done little to tame the Wild West. The climactic mining camp episode included a duel between gunfighters and an attack on the Deadwood Stagecoach by bandits, playing much the same role as that performed by marauding Indians in other performances. In the grand finale, the mining camp was blown away by a cyclone, suggesting that if wild men did not defeat those trying to civilize the West, wild nature surely would.

At heart the Wild West extravaganza was less about the triumph of civilization than ceaseless struggle in which “barbarism and civilization have their hands on each other’s throat,” as one observer put it. Cody could not afford to become so high toned that he robbed the show of the smoke and thunder that many came to see, and he surely welcomed notices like that from a reviewer who promised the public that “Buffalo Bill’s ‘Wild West’ is wild enough to suit the most devoted admirer of western adventure and prowess.” At the same time, Cody promoted the show as family entertainment, suitable for women and children. By hiring Annie Oakley, whom Sitting Bull nicknamed “Little Sure Shot,” Cody graced his cast with a deadly shot who was so demure and disarming that spectators who might otherwise have been scared away by gunplay were as eager to attend as those for whom fancy shooting was the main draw.

European blue bloods also found the show enchanting. In 1887 Buffalo Bill and an entourage of 100 whites, 97 Indians, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 5 Texan steers, 4 donkeys and 2 deer traveled to England to help celebrate the Jubilee Year of Queen Victoria. In addition to staging twice-a-day shows during a five-month stay in London for crowds that averaged around 30,000, the Wild West troupe gave a command performance for the queen in which the Prince of Wales and the kings of Belgium, Greece, Saxony and Denmark rode around the arena in a stagecoach with Buffalo Bill fending off marauding Indians from the driver’s seat. In the process, Buffalo Bill’s pop interpretation of the American frontier was validated as high culture and for the next five years the Wild West toured the major capitals of Europe.

Despite his warm reception throughout Europe, when Buffalo Bill brought the show home in 1893 he was shunned as too commercial by the organizers of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a grandiose celebration of civilization in America that featured 65,000 exhibits in an array of gleaming Beaux Arts buildings dubbed the White City. Undeterred, Buffalo Bill camped out across the street and drew an audience that summer of more than 3 million people, including a group of historians who took a break one afternoon from a conference at the exposition to see the Wild West show and later that evening heard their colleague Frederick Jackson Turner deliver his landmark essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

Turner portrayed the settling of the West as a largely peaceful process, in which the availability of “free land” on the frontier served as a safety valve, releasing social tensions by providing fresh opportunities for Americans who might otherwise have been stifled in their ambitions for a better life. But Cody, for all the historical distortions in his show, hit on a fundamental truth that eluded the erudite Turner: There was no free land. Everything that American settlers claimed, from the landing at Jamestown to the closing of the frontier in 1890, was Indian country, wrested from tribal groups at great cost. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West remains with us to this day because he recognized that fierce competition and strife had as much to do with the making of America as the dream of liberty and justice for all.

Ultimately, it was Indians who lent an air of authenticity to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. He could not hire Indians without the government’s permission and faced scrutiny and criticism from officials who argued that his show displayed Indians as bloodthirsty warriors while the government was trying to convert them to a peaceful, productive existence. But he was keenly aware of their importance to the production and tried to ensure they were well treated. Luther Standing Bear, a Sioux who served as chief of the Indian performers on one European tour, expressed gratitude for the support Buffalo Bill showed when he complained that Indians were being served inferior food. “My Indians are the principal feature of this show,” he recalled Buffalo Bill telling the dining steward, “and they are the one people I will not allow to be misused or neglected.”

Black Elk, whose dictated reminiscences to poet John Neihardt were published in 1932 under the title Black Elk Speaks, shared Luther Standing Bear’s appreciation for the way he and other performers were treated by Buffalo Bill, or Pahuska (Long Hair). When Black Elk wearied of life on tour and said he was “sick to go home,” Buffalo Bill was sympathetic: “He gave me a ticket and ninety dollars. Then he gave me a big dinner. Pahuska had a strong heart.”

But Black Elk’s memories of the show itself were more ambivalent. “I liked the part of the show we made,” he said, “but not the part the Wasichus [whites] made.” Like other Sioux hired by Buffalo Bill, he enjoyed commemorating their proud old days as mounted warriors but seemingly recognized that their role was defined and diminished by what whites made of it. Describing the command performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West for Queen Victoria, he recalled that she spoke to Indian performers after they danced and sang for her and told them something to this effect: “All over the world I have seen all kinds of people; but to-day I have seen the best-looking people I know. If you belonged to me, I would not let them take you around in a show like this.” Whether or not she spoke such words, Black Elk evidently felt that “a show like this” did not do his people great honor.

The willingness of proud warriors who once resisted American authority to join Cody’s show demonstrated that they were capable of adapting to the modern world. Yet the conventions of the Wild West relegated them to the past, a vanishing world of tepees, war bonnets and scalp dances that was the only Indian culture many whites recognized. One chief who toured with Cody, Iron Tail, was said to be a model for the Indian Head nickel, with a bonneted warrior on one side and a buffalo on the other—icons that became cherished as distinctively American only when the way of life they represented was on the verge of extinction.

Sitting Bull, whose appearance in the show prompted many other Sioux to join the traveling troupe, epitomized the wide gulf between the myth perpetuated by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the harsh reality Indians faced with the closing of the frontier. By all accounts he got on well with Cody. But he hated the hustle and bustle of Eastern cities and only stayed with the show for four months. In the years that followed, government officials grew concerned about the emergence of the Ghost Dance, a messianic religious movement on the reservations that promised Indians who joined in the ritualistic dance eternal life in a bountiful world of their own, where they would be reunited with their lost loved ones and ancestors. Reports in late 1889 that Sioux who joined this movement were wearing “ghost shirts,” which they believed would protect them from bullets, increased fears among authorities that the movement would turn violent. When Sitting Bull began encouraging the Ghost Dancers, Maj. Gen. Nelson Miles called upon Buffalo Bill to find him and bring him in, hoping that the chief would yield peacefully to a man he knew and trusted.

Cody headed west to Bismarck, N.D., in December 1890 and reportedly filled two wagons with gifts before setting off in his showman’s outfit to track down Sitting Bull on the Standing Rock Reservation. The escapade is clouded in legend and it remains unclear whether or not Cody was serious about trying to arrest Sitting Bull. In any case he got waylaid by two scouts working for the Indian agent James McLaughlin, who wanted credit for corralling Sitting Bull himself. This was no longer Cody’s show, and it would play out as a reminder of the grim realities that underlay his rousing performances.

On December 15, McLaughlin sent Indian police to arrest Sitting Bull. A struggle ensued, and shots were fired. Sitting Bull was killed instantly. His son, six of his supporters and six policemen also died. Two weeks later, fighting erupted at nearby Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation between a band of Sioux caught up in the Ghost Dance movement and troops of Custer’s old regiment, the 7th Cavalry, after soldiers grappled with a deaf young Indian who refused to hand over his gun. When the shooting stopped, 25 soldiers and about 150 Sioux, many of them women and children, lay dead. In the words of Charles Eastman, a mixed-blood Sioux physician who searched among the victims for survivors, Wounded Knee exposed the lurking “savagery of civilization.”

The massacre marked the tragic end of the real Indian wars.

Also see “The Original Reality Show – Buffalo Bill’s Extravaganza“