When Emerson Hough returned home on a brisk Chicago afternoon in February 1906, his maid reported that a visitor to town had phoned, giving his name as Pat Garrett. Surprised, Hough sat down to write to Garrett, wondering what had prompted the ex-lawman’s unannounced train trip from New Mexico Territory. Garrett’s reply was cryptic. He acknowledged having tried to reach Hough and added, “You will please pardon the unintelligent manner in which this letter is written from the fact that I am suffering a great distress of mind and soul.” Now concerned as well as curious, Hough dashed off another note: “I believe that the best thing you can do is to write me privately and fully and tell me what is wrong. Of course, I have a guess, but I do not want to guess wrong.”

Although it had been a quarter century since Garrett brought down Billy the Kid, at 55 he was still tall and lanky, moody and restless. As a lawman he had been forceful, principled and persevering. His reputation, though faded, had followed him into the 20th century, along with some enemies and many financial woes. With a large family to support, Garrett bet on horses and struggled to put together development schemes that would allow him to wrest a living from the arid land.

The purpose of Garrett’s visit remains a mystery. Had he traveled to Chicago primarily to see Hough? Why not just send a letter or telegram? Was he seeking advice, a loan? The pair had been collaborating on a writing project intended to set the record straight about the entwined lives of Garrett and Billy the Kid. Was that project the impetus for Garrett’s trip? There is no doubt the men were good friends. While much has been written about Garrett’s life, what of Emerson Hough, the man in whom the taciturn Garrett reposed his confidences?

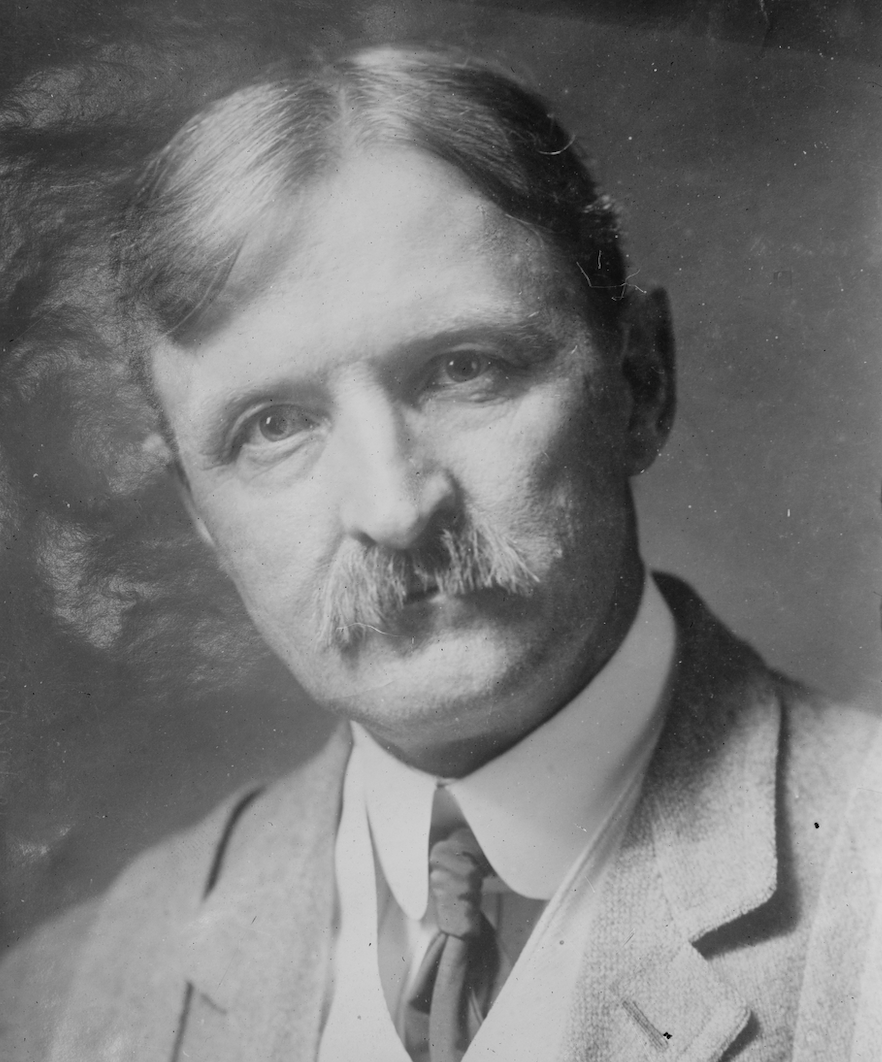

A burly, energetic journalist and novelist, Hough was a chronicler of the American West in its broad sense, someone who contemplated the significance of the nation’s westward movement. The resulting vision, which he continually explored in fiction and nonfiction through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, served as an important literary bridge between the frontier days and modern times. Hough’s novel The Covered Wagon, first published in 1922 and still in print, was adapted by director James Cruze for the silent silver screen in arguably the first epic film to deal with westward migration in the fullness of its geographic and social scope. Hough was well known in his day and is still remembered by many people today as a vigorous champion of America’s vanishing wildlife and landscapes.

Hough (pronounced Huff) was born in Newton, Iowa, on June 28, 1857. Raised to an outdoor life—which he later said helped him cope with bouts of depression and anxiety—he was also well-read as a child and showed an early penchant for writing. In 1880 he graduated from the State University of Iowa with a degree in philosophy, uncertain of his next steps. He worked for a time as a surveyor and in 1882 published his first professional article, in Forest and Stream (a precursor to Field and Stream). At his father’s urging he passed the bar exam and might have settled down locally in his own practice. Instead, when a love affair went south, he headed west, accepting the invitation of a friend a world away in White Oaks, New Mexico Territory, a truly fateful decision.

The friend had invited Hough to join his law practice, and American Field magazine provided Hough a free rail pass in exchange for literary sketches about his Southwest travels. New Mexico Territory was an exciting place in 1883, a land sparsely settled yet alive with stories of bloodshed, courage and cowardice, of sadness, survival and honor. Prospectors combed the desert, battling thirst and claim jumpers. Cattle barons vied with rustlers, and the code of retribution for wrongs real or imagined was prevalent. Billy the Kid was only two years gone, dispatched by Pat Garrett, their legends already finding root in the dry, sandy soil. Hough became intoxicated with the wide country in which he wandered. He remained particularly enamored of the little town of White Oaks, where he practiced little law but passed considerable time at the Golden Era, a local paper. Like wine in a cask, Hough’s memories of White Oaks would one day produce some of his best, most memorable writing.

Hough’s first Western sojourn was remarkably short—little more than a year—but he was a changed man. He returned home to help care for his ailing mother but ever kept turning toward the Western horizon. Back in Iowa he threw himself into his journalistic craft, holding various newspaper positions while also pursuing freelance opportunities. By 1889 Hough had landed a staff position in Chicago with American Field, taking numerous Western assignments. That same year he became the Western representative for Forest and Stream. The positions allowed him to continually gather material for stories about Western life and people, and they gave him keen insight into the environmental changes coming to the Western wilderness. This interest grew into a personal crusade and brought him a lasting friendship with Teddy Roosevelt. Hough notably reported on the illegal slaughter of bison in Yellowstone National Park, sparking public reaction that forced Congress to enact stronger wildlife protection. He declined later offers to superintend both Yellowstone and Grand Canyon national parks.

While passionate about conservation, Hough did not overlook the compelling people and places that loomed large in the nation’s arc of westward expansion. In 1897, a banner year for the writer, he married and also published his nonfiction book The Story of the Cowboy. A history of cowboy life and the cattle industry, it secured Hough’s reputation as a Western writer. Though the book was only a modest financial success, the enthusiastic response of men like Roosevelt and writer Hamlin Garland encouraged Hough to continue his exploration of Western themes and values in fiction while keeping his rigorous schedule as a magazine writer. Hough

published The Girl at the Halfway House in 1900. Although also not a big seller, the book was a thoughtful, objective treatment of issues related to Western settlement.

Hough’s persistence paid off handsomely in 1902 with publication of The Mississippi Bubble, a story of great scope and drama capturing the essence of the westward movement that seemed to Hough to define the American character. Marked by melodramatic prose and plot devices that seem dated to modern readers, the novel is still an intriguing tale related by a storyteller entering his artistic prime.

While he worked long and hard to capture the West in fiction, Hough had other irons in the fire. As copies of The Mississippi Bubble flew off bookstore shelves in 1902, Hough made another expedition out West, this time to meet with Garrett and travel with him to some of the New Mexico Territory sites that marked the lawman’s early career. Garrett, whom President Roosevelt had appointed federal customs inspector in El Paso in December 1901, remained unhappy with an 1882 literary project that, in purportedly telling the life story of Billy the Kid, presented elements of Garrett’s story. That book, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, appeared under Garrett’s byline but actually had been collaboration with Ash Upson, a local friend and enigmatic character. Sensitive to criticism he had not given the Kid an “even break” in their final confrontation, and annoyed by other remarks that impugned the Kid’s courage, Garrett was eager to clear the record, and to reap some reward from his hard-won fame.

The friendship that developed between Hough and Garrett was authentic, not simply opportunistic. Yet each faced pressures that complicated the relationship. Hough yearned to succeed financially as well as artistically; to do so he had to satisfy editors whose notions of what would sell were at odds with his creative impulses. Garrett was dogged by bad luck in business, lacking the knack for details and given to expectations that did not match his skill set. In coming years the friends brainstormed a new treatment of Garrett and his nemesis, and in October 1905 they again traveled to some of the sites tied to the Lincoln County War and its two main protagonists. The writer and the lawman hoped to realize a good return from their effort, Hough later promising Garrett he would “do the right thing by you” should the project succeed.

In the meantime, Garrett ran smack into a political buzz saw. He was conscientious and determined to do well as a customs inspector, collecting duties on beef and other goods coming north across the border. But he brought to the job a somewhat abrasive style, providing ample ammunition to resentful local Republicans in their sustained campaign to have him dismissed. He also ignored or misread signals from the White House regarding the president’s resolve to project a clean-living image. At a 1905 gathering in El Paso, Garrett arranged to introduce to Roosevelt a notorious saloon-owning friend and gambler, presenting him as a cattleman and arranging to have their photo taken together. When the president chose not to renew Garrett’s appointment that December, Hough went out on a limb, inquiring of Roosevelt the basis for his decision and hoping for reconsideration.

In an initial letter Roosevelt indicated that the El Paso photo incident had been annoying but not fatal to Garrett’s chances, and he expressed admiration for Garrett’s past career as one of the “Vikings of the border.” Still, there had been “a great detail of protest from some of the most respectable citizens in Texas and New Mexico.” Then, on December 22, 1905, Roosevelt admitted having his hand forced by the chorus of complaints about Garrett, hard political realities and the limits of patronage: “This is a hard thing for me to write you, because I like you and believe in you. But I want you to understand that Pat Garrett was my personal choice, just, for instance, as Seth Bullock in Deadwood and Ben Daniels in Arizona—both of whom are much of the Pat Garrett stamp—are my personal choices. But if the Department of Justice finds that either of these men does not do his duty, why, he will have to go out.”

The day after Christmas, Hough wrote Garrett to explain what he had learned, putting the best face on the situation:

The President is mighty nice in his letter and speaks of you as “Pat” and with affection. We both know that he personally would like to see you in, and we both know the reason, political and departmental, why he does not reappoint you. Personally, I think this the luckiest thing that could happen to you. Working for a salary is like a horse following a bunch of hay tied in front of his nose. It looks good, but the horse never quite gets it. With your ranch and town site and book work, I reckon the Lord will take care of you some how. I hope you got home safe and are all right.

A little more than a week later, on January 6, 1906, Hough followed up with a short note focused squarely on the book project, asking Garrett to clarify a few historical details. On January 12 Hough wrote again, thanking Garrett for the gift of an intricately carved Mexican cane that had arrived in the mail. Shortly thereafter, in February, Garrett made his mysterious trip to Chicago. Ensuing correspondence between the friends sheds no direct light on Garrett’s visit (indeed, archival notations indicate portions of one or more letters are missing), but Hough’s solicitous comments reflect the concern of both a friend and professional colleague.

What finally came of the Hough-Garrett publishing collaboration was a 1907 volume titled The Story of the Outlaw: A Study of the Western Desperado, in which Garrett and his confrontation with Billy the Kid play a supporting role, rather than the centerpiece as the men had planned. Alternately embracing and rejecting outlaw stereotypes, and at times venturing an unconvincing, unsupported analysis of the criminal character, the book was a rambling collection that profiled various outlaws’ careers.

While Hough was no stranger to arm wrestling with editors and publishers over structure, theme and length, he was thoroughly disgusted. Having shared a portion of his small advance on royalties with Garrett, he sent his partner a copy in February 1907, venting his frustration with the whole enterprise: “I shall be sorry if anything about the work does not please you. I had a great deal of trouble about doing this book; had to change its entire plan, etc., had to stand delay from the publishers, and now I don’t want any more little annoyances from it on their part.…Now, as this book is just out, and as it will be some time before I will get anything from it, and since as it stands you have more out of it than I have, I think we had better let it rest for a while and see if we can’t dig up something for you from this artesian project.”

Indeed, even as he worked to finish the book, Hough had been trying to help Garrett line up investors, first for a copper mine, then development of their “artesian project.” It is unclear how much hope the writer had pinned on his search for capital, but their correspondence confirms Hough did shop Garrett’s proposals among acquaintances in Chicago.

Unfortunately for both men, the book did not do well, prompting Hough to wonder whether there was any commercial value in the kind of Western work on which he labored so hard. Though disappointed, Garrett was more focused in a July 2, 1907, letter to Hough on several points of concern in the text he hoped to discuss with the writer in person. Nothing indicates they ever had that conversation, and the correspondence between Hough and Garrett seemingly ceased. On February 29, 1908, an assassin gunned down Garrett on the road to Las Cruces. On hearing the news, Hough wrote to Garrett’s widow, Apolinaria:

My dear Senora Garrett: In this time of your sorrow, I don’t know whether you care to hear from any one at all, but I thought you might like to have a few words of sincere sympathy at this time.

I knew your husband well. He was a brave and noble man. I am as sure as though I had seen the whole deed that he never was killed in any fair encounter. I know how averse he was to going armed or starting any sort of quarrels.

Now that my friend is gone, I cannot tell you how sad and lonely it leaves me feeling. I wish he might have lived out his life with you all and have succeeded in every ambition he ever entertained.

This news is inexpressibly shocking to me. I send my greeting and regard to you and all your children. I had hoped to see you all at your home some time. Please tell Poe to write to me and give me the particulars of his father’s end. I only saw the newspaper reports, which are not always accurate.

Believe me

Truly your friend.

As the 20th century entered its second decade, Hough soldiered on, working obsessively long hours. This tendency arose both from a strong work ethic and a nervous, high-strung energy, which, along with his periods of depression, might suggest he suffered from a form of bipolar disorder. Growing disenchanted with upheavals stemming from the rise of socialism, as well as the pace and superficiality of modern life, he at times fell into pessimism and didactics.

But in 1922 Hough again struck a vein of rich literary ore with publication of The Covered Wagon, another sweeping story of heroism and determination. This time, though, the author who had long championed the virtues of the rugged individual found his heroes in ordinary pioneers, a people on the move, overcoming arduous challenges on the way to a better day. The success of the book (which earned him $15,000 in serialization rights from The Saturday Evening Post) enabled Hough to sell the film rights for a whopping $30,000. He also penned the screenplay and managed to knock out one more successful novel and screenplay, North of 36, dealing with a cattle drive from Texas. Hough, who had been battling illness, died on April 30, 1923, a week after attending the Chicago premiere of The Covered Wagon.

It is ironic that this man who felt increasingly out of place in the fast-moving 20th century bridged the gap between the novel and the motion picture. Some modern-day critics pan Hough as careless and unreliable with respect to historical precision, one suggesting he is more folklorist than historian. Though he experimented with various forms of writing in more than 34 books and countless articles, it is perhaps a simple, heartfelt note to Pat Garrett that most concisely sums up the values that formed his vision of the West and the people who braved and overcame its dangers, his vision of a life well-lived. After a despondent Garrett had sought him out in Chicago in February 1906, Hough wrote a note inviting the lawman to reply and explain his predicament, promising complete confidentiality. He finished by saying, “We all have hard business times, but in some way they nearly always straighten out after all. Surely you will not lose your nerve, and if a man holds his nerve and tries to do what he knows is right, you can’t keep him from winning out sure in the end.”