The following press report appeared in the Melbourne Argus on May 26, 1948: “This Australian-built CA-15 fighter in a test flight yesterday flew at 502.2 mph—believed to be the highest speed ever attained in Australia by a single-engined aircraft. It was piloted by Flight-Lieut. J.A. Lee Archer in a twofold test and exhibition flight over Melbourne. It reached top speed after pulling out of a 4,000-foot dive. In ordinary level flying it flew at 450 mph—20 mph more than the Mustang’s top speed.”

For a piston-engine airplane to exceed 500 mph, however briefly, was no mean feat. Not until 1969 would American pilot Darryl Greenamyer, flying a heavily modified Grumman F8F Bearcat from Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., establish an official piston-engine speed record of 482.46 mph. Moreover, any fighter with performance superior to the North American P-51D Mustang was not to be taken lightly. That such an airplane was built by a relative newcomer to designing high-performance aircraft, Australia’s Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC), was without doubt an impressive achievement. Just as significant, however, is the date on which the plane made that news-making flight. On October 14, 1947, the rocket-powered Bell XS-1 had broken the sound barrier at a speed of 700 mph. By 1948, jet fighters were already approaching that speed. Whatever its merits, the CA-15 fighter was obsolete before it left the runway.

For Australia, the formidable task of designing a fighter was a case of necessity’s being the mother of invention. In the first few weeks of December 1941, the Japanese effectively crippled the striking power of the United States and Britain, leaving Australia isolated, vulnerable and very threatened. On December 21, CAC began improvising a home-built single-seat fighter from the airframe of its CA-3 Wirraway trainer (a license-built version of the North American NA-33, predecessor of the famous AT-6). The result, completed on May 29, 1942, was the CA-12 Boomerang, of which 250 would be built by 1943.

The Boomerang’s performance did not quite match that of its principal opponent, the Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero, but by the summer of 1942 the Japanese onslaught had abated somewhat, and Allied fighters like the Curtiss P-40E and Supermarine Spitfire were being made available to the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The Boomerang was used to provide ground support in New Guinea, a role in which the agile little plane excelled. A CA-12 was always a welcome sight to Australian troops, and its tactic of jinking about over the jungle at a low level, goading Japanese troops to fire and give away their position (with dire consequences to them if they did), earned it the nickname “Boomer,” Aussie slang for a young male kangaroo.

The Boomerang was developed in a remarkably short time, to the great credit of CAC’s design staff. It also inspired the RAAF to formulate a more ambitious project for the company—a high-performance, long-range, medium-altitude warplane. CAC initially considered simply upgrading the Boomerang, but it soon became clear that its airframe would not be able to accommodate the increases in weight and power involved.

Any further work on the new airplane, however, had to be shelved in the face of a more immediate commitment. In 1943, CAC sent the first of a series of engineering teams to North American Aviation in the United States to prepare to license-produce the Rolls-Royce Merlin-engine variant of the P-51 at the CAC factory at Fishermen’s Bend, Victoria. Meanwhile, the CAC design team began reassessing the RAAF’s 1942 specification, with the revised goal of fulfilling it by creating a successor to the Mustang.

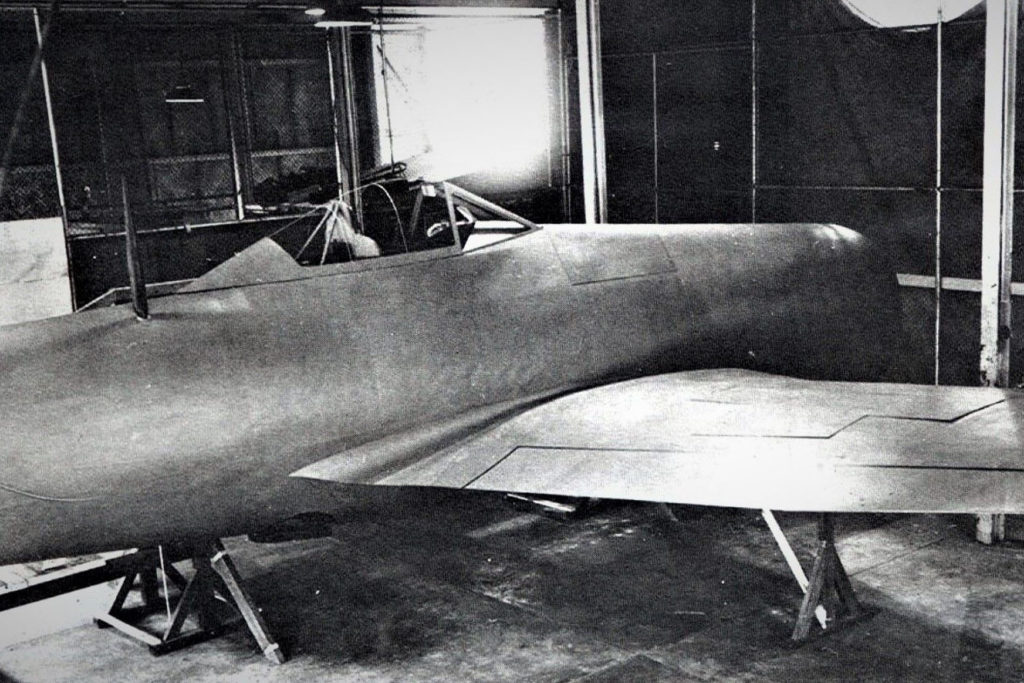

Numerous conferences were held between CAC and the RAAF to finalize the details of the CA-15, as the new fighter was designated. The Mustang’s excellent performance caused the RAAF to continually upgrade its requirements, so it was not until 1944 that a specification was finally agreed upon. Emulating the P-51’s features, the CA-15 was to be an all-metal, stressed-skin aircraft with a semimonocoque fuselage and a wing employing a laminar-flow airfoil section.

Unlike the Mustang, however, the Australian fighter was designed around an 18-cylinder, twin-row Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10W Double Wasp fan-cooled radial engine, with a military rating of 2,000 hp that could be upgraded to 2,300 hp with water injection. A turbosupercharger and intercooler were to be mounted behind the engine. Exhaust gases from the turbo, combined with cooling air from the fan, would be ejected from an efflux duct below the fuselage, thus providing a measure of supplementary thrust.

Shortly after construction finally began on the new design, the CAC team was told that for some inexplicable reason the Pratt & Whitney engine would not be available. After considering alternate power plants, the designers decided to install a Rolls-Royce Griffon 61 liquid-cooled V-12 engine. The designers envisioned using a three-speed supercharger, but until that state-of-the-art feature could be obtained, a two-speed, two-state supercharger was installed as an interim measure.

Changing from an air-cooled radial to an in-line water-cooled engine made it necessary to completely redesign the forward part of the fuselage. In addition, the CAC designers and the RAAF took some time deciding on what sort of armament the new fighter should have. After examining several combinations of 20mm cannons and .50-caliber machine guns, CAC decided to install six .50-caliber guns in the wings, with 280 rounds per gun. The plane was also expected to carry 10 rockets or two 1,000-pound bombs under the wings.

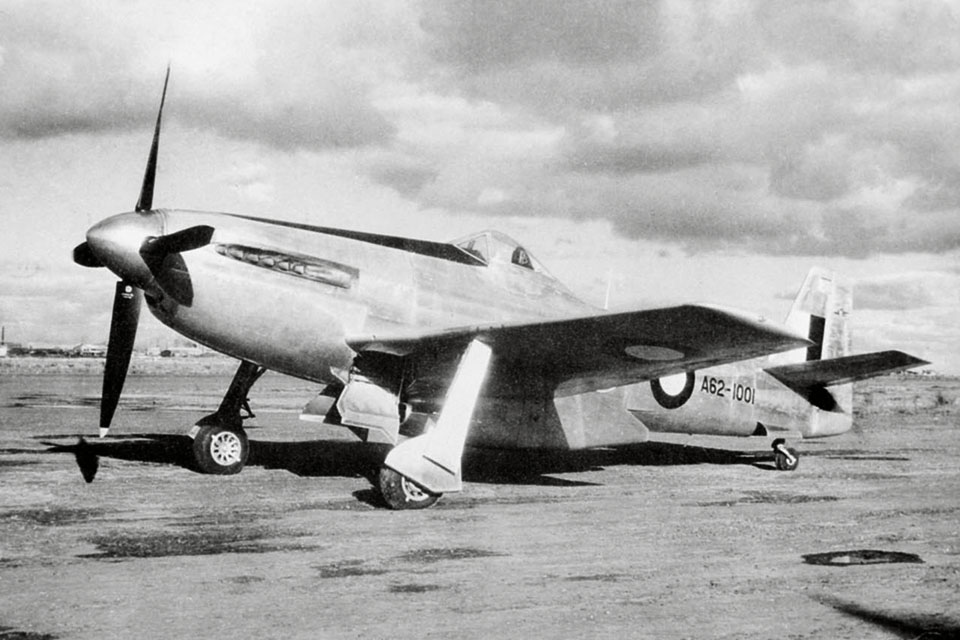

The war in the Pacific was over by the time construction of the CA-15 resumed. Finally, early in 1946, the CA-15 prototype (A62-1001) was wheeled out of CAC’s factory at Fishermen’s Bend. Aside from a somewhat corpulent profile, it did not look bad for a plane that had gone through a radical redesign. It bore a superficial resemblance to the P-51D from some angles. The low-drag, laminar-flow wing, with a maximum thickness of 45 percent chord, was a two-piece structure joined on the fuselage centerline and consisted of formed sheet-metal spars and ribs, with flush-riveted metal skin. The metal-skinned ailerons had shrouded nose balances with fabric seals. The hydraulically operated underwing flaps had a 20-degree setting for takeoff and a 50-degree setting for landing. Fuel was carried in wing tanks accommodating 220 imperial gallons and a fuselage tank containing 40 imperial gallons, which could be supplemented by two 100-imperial-gallon drop tanks under the wings to provide a maximum range of 1,150 miles. The inward-retracting main landing gear used a Dowty Live-Line hydraulic system. The clearest departure from the Mustang’s silhouette could be seen in the horizontal surfaces of the CA-15’s flush-riveted all-metal tail assembly, which were set at a 9-degree dihedral angle.

More Tales from Down Under

The Griffon engine, which was supported by sheet-metal bearers, drove a 12-foot, 6-inch-diameter Rotol constant-speed propeller with compressed wooden blades. The cooling system consisted of a Morris-type, single-row intercooler with a liquid-cooled heat exchanger for the oil system, followed by a three-row main radiator and thermostatically controlled variable efflux. The cooling system was housed under the fuselage in what looked like an exaggerated version of the Mustang’s underside, which probably accounted for the CA-15’s strictly unofficial nickname of “Kangaroo.” The pilot enjoyed an excellent all-around view inside an aft-sliding bubble canopy. Provision was made for the canopy, headrest and rear armor to be jettisoned in an emergency. The wingspan of the CA-15 was 36 feet, with a wing area of 253 square feet. The length was 36 feet 21⁄2 inches, and the height was 14 feet 23⁄4 inches.

When CAC test pilot Jim Schofield took the CA-15 up for its maiden flight at Fishermen’s Bend on March 4, 1946, he made history of a dubious sort—his plane was the last piston-engine fighter prototype of original design to fly. The Soviet Lavochkin La-11 flew somewhat later, but it was no more than a refinement of the La-9. Although CAC already knew that jet turbines were eclipsing its creation, the manufacturer’s trials continued until June 27, 1946. The plane was then passed on to No.1 Air Performance Unit (APU) at Point Cook, Victoria, for calibration and performance trials, which started on July 27. The test pilots involved were Wing Commanders J.H. Harper and G.D. Marshall, Squadron Leaders D.R. Cuming, G.C. Brunner, C.W. Stark and G.H. Shields, and Flt. Lt. J.A. Lee Archer.

Official tests yielded a maximum climb rate of 4,900 feet per minute from sea level to 7,600 feet, flying without guns or ammunition. Range with the normal 220-gallon fuel supply was 1,150 miles. The Griffon 61 engine was rated at 2,305 hp at 7,000 feet.

All of the CA-15’s controls were found to be powerful and positive. In level flight, the ailerons were light at normal speeds, becoming firmer at higher speeds. Elevators were firm at all speeds. The rudder’s handling was firm at normal speeds, but became heavy at higher speeds. Stall tests revealed that there was little warning of the stall, which took the form of buffeting over the tail surfaces at about 97 mph with flaps and undercarriage up, and 90 mph with them lowered, after which the left wing and nose tended to drop slowly. Recovery was quick and normal.

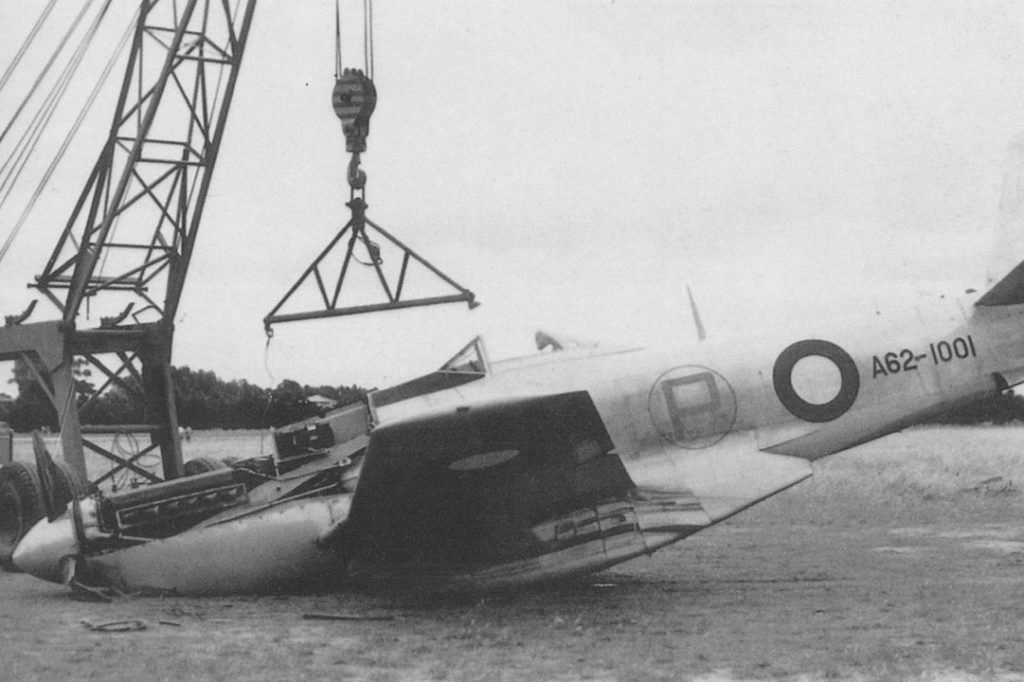

The CA-15 crash-landed on December 10 after a failure in a pressure gauge allowed all the fluid to drain out of both the main and emergency hydraulic systems. Since the RAAF already had a perfectly competent piston-engine fighter in the Mustang and was planning to replace it with jets in the future, the RAAF was in no hurry to proceed with testing the indigenously built CA-15. Consequently, the damaged plane was not returned to CAC for repairs until June 1947.

Meanwhile, the RAAF presented the results of its test flights on May 27, 1947. Its conclusion was: “In general the CA-15 is a very pleasant, straight forward aeroplane, easy to fly and with no apparent vices. The view in flight is very good, particularly over the nose. At present handling is marred by the excessive change of rudder trim with variation of power and/or speed. When this is cured a very pleasant aeroplane should result.” What the report neglected to mention was that no amount of improvements at that point would be likely to earn the CA-15 a production contract.

The repaired CA-15 was delivered to No.1 Aircraft Depot at Laverton, Victoria, for the chief technical officer’s inspection on May 19, 1948. On May 20, it was transferred to the Aircraft Research and Development Unit (ARDU), RAAF Laverton, and on May 25 Flt. Lt. Lee Archer made his eyebrow-raising flight over Melbourne. But that news-making flight marked the climax of a design whose promise had been lost years before. A limited test program continued until 1950, during which an official maximum speed of 448 mph was attained at 26,400 feet. The service ceiling was 34,000 feet. What the plane could have done had it received the Griffon with the three-speed supercharger would never be known—and in any case was a moot point.

The end came on February 7, 1950, when Air Board Agendum No. 9530 recommended that flying of the CA-15 cease because a lack of spare parts made it uneconomical to maintain the airplane. Also, the Department of Supply and Development requested that the two Griffon engines, which had been supplied on loan from Great Britain, be returned. Finally, on May 1, 1950, the CA-15 was transferred from ARDU to No. 1 Aircraft Depot for conversion to components.

Had it been completed in 1943 or even 1944, the CAC CA-15 would undoubtedly have been one of the outstanding aircraft of World War II. Instead, an ironic combination of immediate wartime need, followed by the lack thereof, so delayed its gestation that by the time it finally did take to the sky, it had become no more than a footnote in the epilogue of piston-engine fighter aircraft.