As with other members of the Commonwealth, Australia made a significant contribution to the British war effort during World War II. Although there was a separate Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a great many Aussie airmen preferred to get into Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF), hoping to get into action earlier and see more combat. Many of them gained notoriety in both air arms, often as much by virtue of their individualistic personalities as their prowess. Indeed, the highest-scoring of Australia’s fighter pilots, Clive Caldwell, embodied uncommon character as well as flying skills. He saw action with both the RAF and the RAAF against all three of Britain’s principal enemies: Germany, Italy and Japan.

Born in Lewisham, outside Sydney, on July 28, 1911, Clive Robertson Caldwell attended Albion Park School and Trinity School in Sydney before becoming a commission agent in Rose Bay. He also joined the Royal Aero Club of New South Wales, taking his first flying lessons in 1938 and soloing after only 31⁄2 hours of instruction. He had 11 flying hours in his logbook when Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. Caldwell joined the RAAF on the same day, only to learn that he was three years above the maximum age for fighter training. He overcame that obstacle by having his birth certificate altered to state that he was 26.

Caldwell took the RAAF officer’s pilot course in February 1940, but when it became clear that all the trainees were slated to become instructors, he resigned, then rejoined and started over on May 6 as a second class aircrew trainee at the Empire Air Training School in Sydney. After attending the Elementary Flying Training School at Mascot and the Service Flying Training School at Wagga Wagga, Caldwell received his commission as an acting pilot officer on January 12, 1941. During wartime, 30-year-old pilots were more likely to serve in transports than fighters, but Caldwell’s exceptional flying skill earned him a combat assignment—not to Britain to fly Hawker Hurricanes or Supermarine Spitfires, but to Advanced Headquarters, RAF Western Desert, in North Africa. After arriving there on April 11, Caldwell was posted on May 5 to No. 250 Squadron in Palestine, which had just formed with a complement of American-built Lend-Lease Curtiss Tomahawk Mark IIBs. After a few ground-attack missions over Vichy French Syria, he and two squadron mates briefly constituted the fighter defense of Cyprus until he rejoined No. 250 Squadron’s main contingent in Egypt. There, he found the action he sought over the Libyan port of Tobruk, cut off and under siege by the Italian army and German Maj. Gen. Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps.

On June 6, 1941, Caldwell helped Flight Lt. J. Hamlyn bring down an Italian Cantiere Cant Z.1007bis bomber. Caldwell’s first official victory came while escorting Bristol Blenheims on a bombing strike to Gazala on June 26, during which he shot down a Messerschmitt Me-109E three miles west of Fort Capuzzo and damaged another. His victim was Lieutenant Heinz Schmidt of I Gruppe, Jagdgeschwader 27 (I/JG.27), the crack “Afrika” fighter wing whose ranks included the highest-scoring Luftwaffe ace in the west, Hans-Joachim Marseille.

By that time, Caldwell had flown 40 operational sorties and was less than satisfied with the results—especially his aerial marksmanship. One day, while returning from a patrol, he looked down and noticed the stark shadows his squadron’s planes cast on the desert below. Taking aim on one of them, he opened fire and noted the fall of his shot relative to the shadow. In that manner, he realized that he could assess the necessary deflection for hitting a moving target, and he experimented further until he acquired a feel for deflection shooting at different angles and speeds. Once he mastered that technique, Caldwell abandoned the use of tracer bullets to zero in on a target—often when he was attacked by enemy fighters their first tracer volley served only to warn him of their presence, at which point he could take evasive action. By relying only on marksmanship, Caldwell reckoned he could strike before his opponents knew what hit them.

On June 30, Caldwell put his newly acquired skill into practice when he sent a Messerschmitt Me-110 of III Gruppe, Zerstörergeschwader (destroyer wing) 26, crashing into the sea off Tobruk, as well as the two Junkers Ju-87Bs of II Gruppe, Sturzkampfgeschwader (dive bomber wing) 2 (II/StG.2), that the 110 was escorting on a dive-bombing mission over the beleaguered town. On July 7, he downed a Fiat G.50 southeast of Gazala. He damaged Me-109s on July 12 and August 3; shared in the destruction of another G.50 during a convoy patrol on August 16; damaged an Me-109 two days later; and probably downed another Me-109 on the 28th.

It should be noted at this point that some discrepancies exist between the dates in Caldwell’s logbook and the official squadron records. In any case, his squadron mates took note of his rising score, and soon his method of “shadow shooting” became a standard method of gunnery practice in the Desert Air Force. He also acquired a somewhat unwelcome nickname. “Clive Caldwell was given the sobriquet ‘Killer’ (a name not of his choosing or liking) due to his habit of shooting up any enemy vehicle he saw below when returning from a sortie,” recalled Wing Commander Robert H. Gibbes, who flew in No. 3 Squadron RAAF at that time and later served under Caldwell’s command in the southwest Pacific. “Invariably he landed back at his base with almost no ammunition left.”

At about that same time, Caldwell’s commander, Squadron Leader John E. Scoular, made a more critical notation in the new ace’s logbook: “An extraordinarily keen fighter pilot who is apt to let his keenness get the better of him. Needs more practice in leading and will turn out a very good pilot. At the moment he is purely an individualist.”

Given the high caliber of his German opposition, it was perhaps inevitable that Caldwell would meet his match. On August 29, he was jumped northwest of Sidi Barrani by two Me-109E-7s of JG.27’s 1st Staffel—one of which bore the black number 8 of Lieutenant Werner Schroer. The Germans’ first firing pass wounded Caldwell in the back, left shoulder and leg. Their second attack sent a round through his canopy, wounding him in the face and neck with Perspex splinters and shrapnel. Two cannon shells passed through the fuselage just behind him and damaged the right wing.

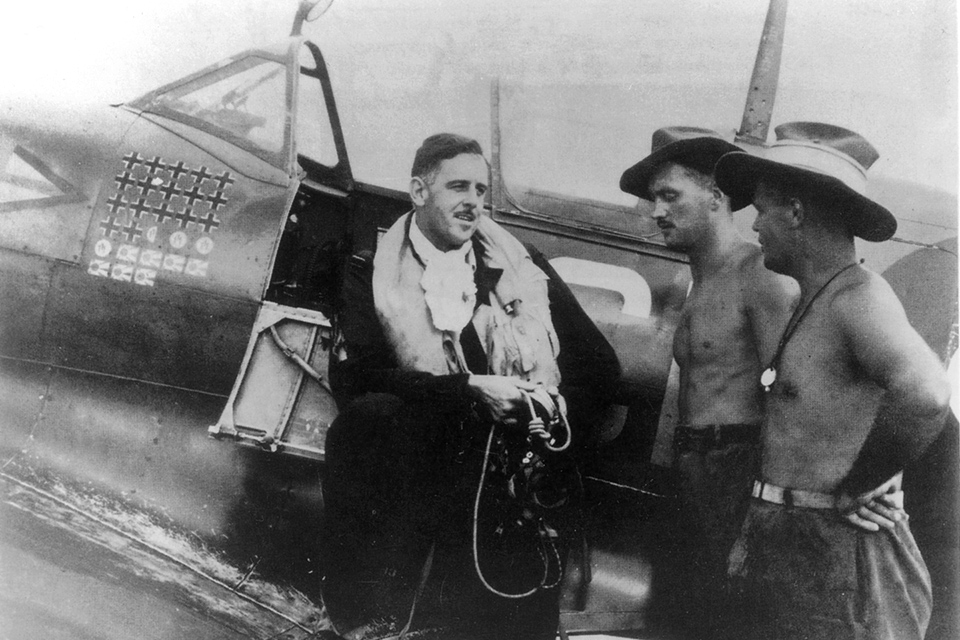

Caldwell later said that all that punishment left him feeling “quite hostile,” causing him to turn on his attackers and shoot one of the Me-109s down in flames. Schroer, evidently unnerved by that sudden turn of events, hastily retired, but was credited with the Curtiss as his sixth victory (of an eventual 114 in only 197 missions). At that point, Caldwell’s engine caught fire, but by violently sideslipping, he managed to extinguish it and nursed his Tomahawk back to his air base at Sidi Haneish. His plane was a wreck, riddled with more than 100 7.92mm rounds, as well as five 20mm shells that punctured a tire and disabled his flaps, but he managed to land safely. For his dogged courage during that action, Caldwell was promoted to flight lieutenant and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). After recovering from his wounds, he was soon back in action, downing Me-109s on September 27 and 28 and damaging another on the 30th. At that point, the Germans were aware of the aggressive Australian and were referring to him by a sobriquet of their own: “Tiger” Caldwell.

Promoted to the rank of flight commander, Caldwell resumed his scoring during Operation Crusader, the British offensive intended to relieve its forces cut off and besieged in Tobruk—starting with an Me-109F-4/Trop over Tobruk on the morning of November 23. That evening he engaged four Me-109s over Baheira and shot down the lead Messerschmitt. Its pilot, Captain Wolfgang Lippert, commander of II/JG.27 and a Knight’s Cross holder who had just downed a Hurricane for his 30th victory, bailed out but was struck by his vertical stabilizer, which broke both of his legs. Taken prisoner, Lippert was sent to a hospital in Egypt, where in spite of both infected legs being amputated he developed an embolism after the operation and died.

Caldwell damaged an Me-109 on November 26 and probably downed two more on the 29th and 30th. On December 5, the Axis launched another strike on Tobruk. Caldwell, flying his usual Tomahawk, serial No. AK498, bearing the call letters LD-C, was leading a patrol toward El Adem when he encountered a large escorted gaggle of Ju-87Rs from I/StG.1, II/StG.2, I/StG.3 and the Italian 239th Squadriglia Autonomo Bombardimento a’ Tuffatori. His combat report described what ensued:

…was leading the formation of two squadrons, No. 112 acting as top cover to No. 250 Squadron, sent to patrol a line approximately ten miles west of El Gubi, and had just reached this position at 1140 hours when I received [radio] warning that a large enemy formation was approaching from the northwest at our height. Both squadrons climbed immediately, and within a minute the enemy formation, consisting of Ju-87s with fighter escort, was sighted on our starboard side. No. 250 Squadron went into line astern behind me and as No. 112 Squadron engaged the escorting enemy fighters, we attacked the JUs from the rear quarter.

At 300 yards I opened fire with all my guns at the leader of one of the rear sections of three, allowing too little deflection, and hit No. 2 and No. 3, one of which burst into flames immediately, the other going down smoking and went into flames after losing about 1,000 feet. I then attacked the leader of the rear section…from behind and below, opening fire with all guns at very close range. The enemy aircraft turned over and dived steeply down with the root of the starboard wing in flames. I then opened fire again at another Stuka at close range, the enemy catching fire and crashing in flames near some dispersed mechanical transport. I was able to pull up under the belly of one of the rear, holding the burst until very close range. The enemy aircraft dived gently straight ahead, streaming smoke, then caught fire and dived into the ground.

In addition to destroying five Ju-87s—the last two of them from the 239th Squadron, piloted by Sub-Lieutenant Stefonia and Sergeant Mangano—Caldwell damaged one of their Italian Macchi C.200 escorts. Other members of No. 250 Squadron contributed to the “Stuka Party,” two falling to Sergeant Robert J.C. Whittle. Pilot Officer Neville Bowker of No. 112 Squadron claimed three, and Pilot Officer John P. Bartle claimed one, along with a Fiat G.50. On December 7, Tobruk’s garrison had cause to celebrate as the Eighth Army drove its Axis besiegers back and relieved the town. On the other side of the world, however, Japanese carrier planes were attacking the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, on the Hawaiian isle of Oahu. War had broken out in the Pacific—and was soon to come much closer to Caldwell’s homeland.

Continuing his desert rampage, Caldwell destroyed an Me-109 between Derna and Tmimi on December 12, damaged two on the 14th, probably downed one on the 18th and damaged another on the 19th. He shot down two Me-109s and damaged a third in the Agedabia area on the 22nd, and six days later he returned to that German air base, strafing two Ju-87s on the ground and setting them on fire.

On December 26, Caldwell was awarded the DFC and Bar, honoring him for 12 victories—although by that time he had raised his score to 17. On January 6, 1942, he was given command of No. 112 Squadron, which had just received improved model Curtiss Kittyhawk Mark IAs and decorated their front cowlings with its distinctive shark mouth marking, which had already inspired a similar practice by the American Volunteer Group in China. Caldwell tested the newer Curtiss types for use as fighter-bombers, but also found time to engage and damage Me-109s on January 8 and 26.

On February 10, No. 112 Squadron got a contingent of 12 Polish ferry pilots who had volunteered for fighter training, and Caldwell took them under his wing. On the 21st, Caldwell’s flight ran into six Me-109Fs from I/JG.27, and although he was credited with downing one of them—whose pilot, 2nd Lt. Hans-Arnold Stahlschmidt of the 2nd Staffel (2/JG.27), crash-landed between Derna and Gazala—the Germans shot down three Kittyhawks, including two of his Poles, Sergeant Józef Derma and Lieutenant Witold Jander, the latter of whom was wounded. Caldwell damaged Me-109s on February 23 as well as on March 6, 8 and 9. He destroyed an Me-109 and damaged another on the 11th.

Caldwell probably downed an Me-109 on March 13, but on that same day Jack Bartle and Sergeant Jerzy Rózánski became detached from a 12-plane formation on patrol near Tobruk and were ambushed by Master Sgt. Otto Schulz of 4/JG.27. Both “Sharks” crashed, but both pilots survived. The Poles got revenge the next day when Caldwell downed a Macchi C.202 northwest of Tobruk and teamed up with Sergeant Zbigniew Urbánczyk to claim another.

The destruction of an Me-109F near Tobruk on April 23 brought Caldwell’s official score to 201⁄2, making him the top-scoring Allied ace in North Africa. Meanwhile, Australia faced a new threat of its own—on February 19, 1942, the same Japanese Combined Fleet that had crippled Pearl Harbor mauled Port Darwin. On March 16, twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M1s of the Takao Kokutai (naval air group), based at Kupang on the newly seized island of Timor, flew the first of a series of bombing raids on northwestern Australia. Their first opposition came on March 28 from Curtiss P-40Es of the 9th Squadron, 49th Pursuit Group, U.S. Army Air Forces, which shot down one bomber. On the 30th and 31st, however, the G4M1s—code-named “Bettys” by the Allies—returned to Darwin with fighter escorts, in the form of Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeroes of the 3rd Kokutai.

As intermittent bombing raids continued, the Australian government named Caldwell among the personnel that it wished to have shipped home. At first Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, commander in chief, RAF Middle West Command, refused, but in May 1942 he finally agreed to release Caldwell. Although still an individualist, Caldwell had grown into his responsibilities as commander of No. 112 Squadron. As he left Cairo for England on May 13, Tedder commended him as “a fine commander, an excellent leader and a first-class shot.”

In reaction to the Japanese threat to the northern territories, Australian Prime Minister John Curtin appealed to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to send him Spitfires. Due to the higher priority placed on the desert war, only six Spitfire Mk.VBs reached Australia on August 13, 1942, but 43 more arrived in October. Meanwhile, in England, Caldwell served for a time in the Kenley Wing to familiarize himself with the Supermarine fighter. From there, he was shipped across the Atlantic and the United States, finally returning to Australia in September 1942.

First posted to No. 2 Operational Training Unit (OTU) to test and instruct new pilots to fly the indigenously produced Commonwealth CA.13 Boomerang fighter, Caldwell was promoted to wing commander, and in January 1943 he was put in command of the Spitfire-equipped 1st Fighter Wing at Darwin, made up of No. 54 Squadron, RAF, and Nos. 452 and 457 squadrons, RAAF.

The Japanese curtailed their air attacks on Australia after August 23, 1942, as their attention shifted to the American invasion of Guadalcanal. On February 6, 1943, however, Flight Lt. Robert W. Foster of No. 54 Squadron caught a Mitsubishi Ki.46 photoreconnaissance plane of the Japanese army’s 70th Independent Squadron and sent it crashing into the sea. That reconnaissance flight was the prelude to a new campaign of harassment attacks on northern Australia by the 753rd Kokutai (as the Takao Kokutai had been redesignated after a reorganization of Japanese naval units on November 1, 1942) from its base at Lautem on Timor, with Zero escorts provided by the 202nd (as the 3rd Kokutai had been redesignated) from Kendari in the East Indies. The incident also showed that the sleek, twin-engine Ki.46’s outstanding speed and high altitude performance would not be enough to protect it from the newly arrived Spitfires.

The first raid came on March 2, when nine G4M1s of the 753rd Kokutai, escorted by 21 Zeroes of the 202nd, bombed Coomali. Caldwell led 12 Spitfires each from Nos. 54 and 457 squadrons against them and encountered the Zeroes 30 miles west-northwest of Port Charles. In the first major clash between the Spitfire and the equally legendary Zero, the Japanese fighters—flown by such experienced aces as Lieutenant Takehide Aioi (10 victories) and Petty Officer 2nd Class Kiyoshi Ito (17 victories)—acquitted themselves remarkably well. The Spitfire pilots also found themselves plagued by technical problems, particularly a tendency of their 20mm Hispano cannons to freeze up due to the contrast between the high temperature and humidity on the ground and the much lower temperatures at altitude. Nevertheless, Caldwell was credited with shooting down a Zero (by then code-named “Zeke” by the Allies) and a Nakajima B5N2 torpedo bomber (“Kate”), while Squadron Leader Eric M. Gibbs of No. 54 Squadron claimed a second Zeke. The 202nd Kokutai’s records, however, indicated no losses at all, and while the group certainly had Zeroes, it possessed no torpedo bombers. For their part, the Zero pilots claimed three “Bell P-39s” and “Brewster F2A Buffalos” in the fight, but Caldwell’s Spitfire squadrons had suffered no casualties, either.

After some small raids on March 3 and 5, and the loss of another Ki.46 to No. 457 Squadron on March 7, the Japanese launched their next major effort on March 15, when 19 G4Ms of the 753rd Kokutai bombed the U.S. Army headquarters, oil storage tanks and rail line at Darwin. This time the bombers came escorted by 26 Zeroes of the 202nd Kokutai, which were intercepted by 27 Spitfires of Nos. 54 and 452 squadrons, led by No. 452’s Squadron Leader Raymond E. Thorold-Smith. This was only Thorold-Smith’s second encounter with the Japanese, and he was one of two Australian pilots killed that day, while two other pilots survived the destruction of their Spitfires. No. 1 Wing claimed nine attackers shot down, four probably destroyed and six damaged. In fact, eight of the notoriously flammable G4M1s were damaged, yet all made it back. The 202nd Kokutai lost only one Zero and its pilot, Petty Officer 2nd Class Seiji Tajiri, while claiming 11 Spitfires and five “probables.” Significantly, the 202nd Kokutai’s after-action reports noted that most of the Spitfires had tried to dogfight with them—something that was advantageous against Me-109s during the Battle of Britain but suicidal against Zeroes. Two exceptions were Flight Lt. Edward Hall and Malta veteran Pilot Officer Adrian P. Goldsmith of No. 452 Squadron, who used climb and dive tactics instead, resulting in Hall’s being credited with a Zeke, and Goldsmith’s claiming a Zeke and a Betty.

On May 2, 18 G4M1s attacked Darwin, dropping their bombs on its airfield before being attacked 40 miles northwest of the port by 33 Spitfires led by Caldwell. In the 15-minute, 20-mile running fight that ensued, Caldwell was credited with a Zeke and a “Hamp” (the Allied code name for the Zero’s clipped-wing A6M3 Model 32 variant), and his wing claimed a total of seven Japanese destroyed, four probables and seven damaged. In fact, all 26 of the 202nd Kokutai’s fighters returned, as did all the 753rd’s bombers, although seven Zeroes and seven G4Ms were damaged. The defenders lost 14 Spitfires, five of them directly attributable to combat, and two pilots. Four others came down due to mechanical failures, and four force landed when they ran out of fuel. After the constant-speed unit controlling the pitch of his propeller failed—a chronic problem in the Spitfire Mk.V—Flight Lt. Ross Stagg of No. 452 Squadron had to bail out at sea, took to his dinghy, paddled his way to Fog Bay and finally rejoined his unit on May 17.

Even discounting the 202nd Kokutai’s exaggerated claim of 21 Spitfires, by any standard the May 2 Darwin raid had been a defeat for Caldwell’s wing—rendered more embarrassing when General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters released an official communiqué referring to the “heavy casualties” the Spitfires had suffered. Australian newspapers ran with the story, and editorials spoke with alarm of a “serious reverse.”

The Japanese attacked Millingimbi on May 9 and 28, resulting in the losses of three Spitfires and five Zeroes. On June 17, a Ki.46 reconnoitered the region and managed to elude 42 Spitfires that tried to intercept it.

Three days later the Japanese army struck at Australia, with 18 Nakajima Ki.49 Donryu (“Dragon Swallower”) bombers of the 61st Sentai (regiment) attacking Winnellie and nine Kawasaki Ki.48s of the 76th Sentai hitting Winnellie and Darwin. They were escorted by 22 Nakajima Ki.43 Hayabusa (“Peregrine Falcon”) fighters of the 59th Sentai, while two Ki.46s monitored the results. Caldwell led 46 Spitfires against them and claimed nine bombers and five fighters shot down, as well as eight bombers and two fighters damaged. Caldwell himself was credited with destroying a Zeke and probably downing a Betty southeast of Darwin. The Japanese army recorded the loss of one Ki.49 and one Ki.43, as well as another shot-up Ki.49 and two Ki.48s force landing upon their return to base. The 59th Sentai claimed nine Spitfires and six probables, but the 1st Fighter Wing actually lost three Spitfires and two pilots.

On June 22, Caldwell received the Distinguished Service Order. The citation noted that “by his confidence, coolness, the skill and determination of his leadership in the air, and the offensive spirit he displays at all times, he has set the most excellent example to all pilots of the Wing.”

On June 28, the Japanese navy returned to Darwin with nine G4Ms and 27 Zeroes. Caldwell intercepted them with 42 Spitfires and claimed that his wing destroyed four fighters and probably downed two bombers—himself accounting for one Zeke and one of the probable Bettys—at the cost of two Spitfires damaged in crash landings. The 202nd Kokutai only recorded three Zeroes damaged, but the 753rd noted that one of its bombers crash-landed at Lautem West, while another suffered an engine fire that was snuffed out by newly installed automatic fire extinguishers.

An Allied buildup of bombers in the Darwin area and raids by Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the American 380th Bomb Group induced the 753rd Kokutai to dispatch 23 bombers to strike at the 380th’s air base at Fenton on June 30. Upon reaching the coast, the Bettys were intercepted by Caldwell and 38 Spitfires and closed ranks while the 202nd Kokutai’s Zeroes intervened. As a result of such disciplined mutual defense tactics, the Japanese bombers destroyed three B-24s and a Curtiss-Wright CW-22 trainer on the ground, and damaged another seven B-24s. Caldwell was credited with shooting down a Zeke and a Betty 65 miles west of Batchelor, and his wing claimed a total of seven enemy planes, five probables and 11 damaged for the loss of five Spitfires in combat and two to engine failure. The 202nd Kokutai claimed 16 Spitfires and three probables without loss. The 753rd reported one riddled G4M1 that had to be written off after crash landing near Lautem.

Fenton was the target of the last Japanese daylight raid on July 6. Further raids occurred at night, but they, too, became less frequent. On August 17, three Ki.46s reconnoitered the region in preparation for the next strike, but all three were shot down by Spitfires of Nos. 452 and 457 squadrons. When a fourth Ki.46, temporarily attached to the 202nd Kokutai, ventured over the area that same afternoon, it was caught by Caldwell 20 miles west of Cape Fourcroy, and its crew, Sergeants Tomihiko Tanaka and Kenji Kawahara, were killed. That brought Caldwell’s confirmed total to 28l⁄2.

After making a strafing attack at Brock’s Creek on September 7, the 202nd Kokutai was transferred from Kendari to Rabaul in response to American advances into Merauke in southwestern New Guinea. The last bombs fell on mainland Australia on the night of November 11-12, 1943, when eight G4M1s attacked Fenton. Flying Officer Jack Smithson intercepted the raiders and claimed two. The Japanese lost only one bomber that night, but its crew included the 753rd Kokutai’s executive officer, Commander Michio Horii, and a squadron commander, Lieutenant Takeharu Fujiwara. Those losses gave a jolt to the group’s morale, and the 753rd’s airmen may have felt relieved when its transfer orders came—not due to its losses, which had not really been crippling, but because of the greater threat that the advancing Allies posed in New Guinea and the Solomons. Rather than being outfought by Caldwell and his Spitfire wing, the 202nd and 753rd kokutais had simply been outflanked.

Australia rightly acclaimed Caldwell for his efforts in the country’s defense. Less welcome to him was being taken off operations on September 23, 1943, and made command flight instructor at No. 2 OTU in Mildura. He returned to the front on April 14, 1944, when he was put in command of No. 80 Fighter Wing, including Nos. 79, 452 and 457 squadrons, now equipped with the Spitfire L.F. Mk.VIII, which Caldwell called “the most elegant military aircraft I ever flew.” On August 1, he was promoted to group captain, and in December he took the wing to Morotai, midway between New Guinea and the Philippines. No. 80 Wing’s task was to protect the island, but the unit’s Spitfires had little to do but intercept occasional bomber strikes and strafe the enemy on the ground. In January 1945, Air Commodore Arthur H. Cobby, commander of Tactical Air Force, RAAF, selected Caldwell to command an Australian task force participating in the final offensive against Japan. Soon afterward, however, the Allied command assigned the Australians to support operations in the East Indies. Caldwell and seven other officers bitterly objected to having a minor fighting role imposed on them. As the wing’s spokesman, he sought to resign from the RAAF in protest, but was instead attached to headquarters of the First Tactical Air Force, RAAF, and then to Melbourne in May 1945.

After the war, the RAAF discovered that Caldwell had been flying alcoholic spirits to Morotai, where his batman sold them to U.S. servicemen at a substantial profit. The Australian ace was court-martialed and reduced to the rank of flight lieutenant. He petitioned the governor general against the sentence, but when that failed he left the RAAF on February 6, 1946.

This cloud hanging over Caldwell’s career proved to have a silver lining. Taking advantage of his American contacts, he spent the rest of 1946 purchasing surplus aircraft and other military equipment from the U.S. Foreign Liquidation Commission in the Philippines, then resold it in Australia and elsewhere. Deciding that he enjoyed the import-export business, Caldwell plunged into that new venture as he did everything else in life, with all-out energy.

Soon after joining an import-export firm in Sydney, he became its managing director, and the leadership skills he had acquired in wartime elevated him to chairman of the board in 1953. As he had in the squadrons and wings he commanded, Caldwell exuded confidence and disdained inefficiency in any form, always setting an example and never expecting anyone to do a job he could not do himself. Under his direction, his company expanded rapidly, opening subsidiaries throughout Australia and the world.

Even in retirement, Caldwell embodied the somewhat larger-than-life image that Australia still presents to much of the world. Standing 6 feet 3 1/2 inches tall and weighing 238, he could still drive a golf ball 50 to 60 yards farther in the 1960s than the average player.

Clive Caldwell died on August 5, 1994, but to this day he remains one of the immortal characters of the RAAF—and of Australian history in general.

For further reading, Aviation History senior editor Jon Guttman recommends Aces High, by Christopher Shores and Clive Williams.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2005 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!