Renowned as the Pacific War’s most successful fighter, the Grumman F6F also contributed to Allied victory in the European theater.

Four Grumman F6F-5 Hellcats swept in from the sea, hunting enemy aircraft attempting to get out from under the U.S. Navy’s aerial umbrella. Heading inland, the fighter leader spotted two twin-engine bombers bearing enemy markings on their wings. The setup was nearly ideal: The leader and his wingman nosed down, lined up the nearest target in their reflector gunsights and pressed the triggers on their stick grips. Motes of light played over the camouflaged bomber, which absorbed the full impact of 12 .50-caliber machine guns. It gushed smoke, descending rapidly and smashed into the ground.

Another successful shootdown in the Pacific? No, a Heinkel He-111 had just become the first German victim of Navy Hellcats over Europe.

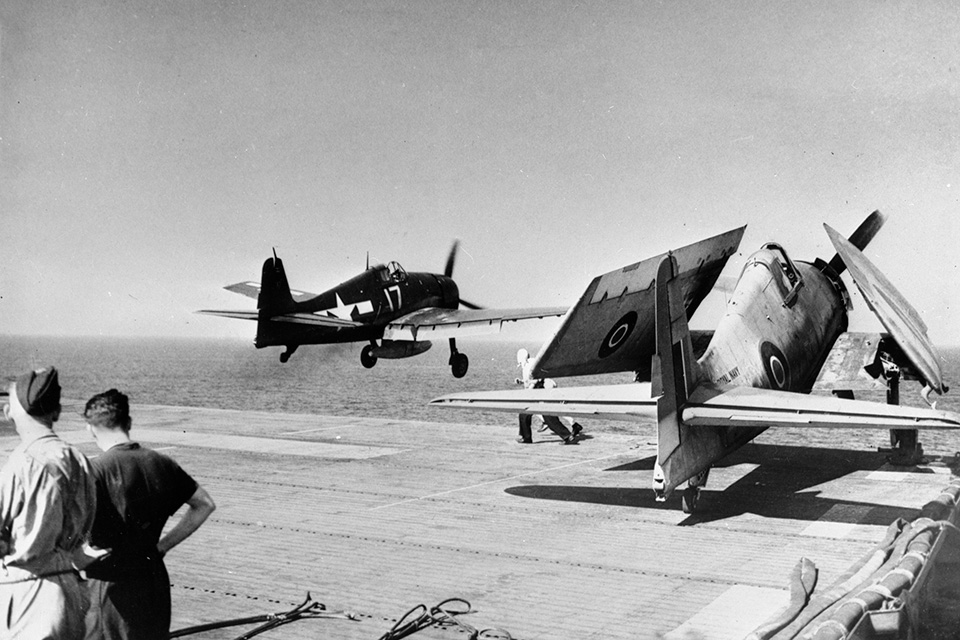

The date was August 19, 1944, the location southern France. Hellcats had been gaining air superiority over the central and western Pacific for 12 months, but the pedigreed feline from Long Island also extended its claws against Germany, in a truly world war. Its service encompassed the last 13 months of combat in the European Theater of Operations, flying with the British and U.S. navies.

Britain was a steady customer of Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company, as the Royal Navy badly needed high-performance fighters. Ian Cameron, a British naval aviator, lamented, “Between the first day of war and the last, the Fleet Air Arm received not one single British aircraft which wasn’t either inherently unsuited for carrier work or was obsolete before it came into service.”

The British bought nearly 1,100 Grumman Martlets (their name for the F4F Wildcat) between 1940 and ’44 and 2,000 Vought Corsairs beginning in June 1943. The following month No. 800 Squadron swapped its Hawker Sea Hurricanes for F6F-3s, designated Gannet Is after the northern seabird and renamed Hellcat Is in January 1944. Ultimately the Royal Navy obtained 252 F6F-3s and 930 F6F-5s (as Hellcat IIs), including some night fighters. The first British Hellcats entered combat in April 1944, in an environment far removed from the F6F’s familiar Pacific climes.

The German battleship Bismarck had been sunk in May 1941 but three years later its sister ship Tirpitz still lurked in Norway’s fjords, representing a potential threat to Allied shipping. In early April two British fleet carriers and four escort carriers deployed to northern waters intending to end that threat. The embarked squadrons included No. 800 aboard HMS Emperor, steaming 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

The operational plan involved two strikes, each with 21 Fairey Barracuda dive bombers escorted by 20 Hellcats and Martlets. The first aircraft launched early on April 3, 1944, 120 miles from the target. The Royal Navy aviators flew low—some at just 50 feet—to minimize chances of German radar detection. Almost 90 minutes later the first strike force sighted Tirpitz’s 45,000-ton bulk nestled in the craggy protection of Kaafjord. The defenders spotted the attackers inbound and spooled up smoke generators while some of the thickest flak seen in Scandinavia erupted in the frigid air.

“The first strike caught the Germans with their trousers down,” said Sub-Lt. Donald Sheppard. In the pale, slanting light the Grummans dropped into their dives, strafing to suppress anti-aircraft fire. They were surprisingly effective, as only one dive bomber was shot down. In exchange, the ungainly Barracudas claimed six hits.

Little more than an hour later the second strike rolled in. By then the Germans were fully alert, and their gunners downed a Barracuda and a Hellcat, but as many as nine more bombs rocked the battleship with direct hits or near misses. The fighter leader, Lt. Cmdr. Stanley Orr, concluded, “The Hellcat proved itself to be an excellent gunnery platform on this mission.”

Tirpitz was out of commission until June, but subsequent attacks achieved few results owing to heavy weather. Another Hellcat squadron, HMS Furious’ No. 1840, covered the next to last effort, which claimed only light damage to the ship.

Tirpitz ultimately was sunk by Royal Air Force Lancasters in November 1944.

A month after the first Tirpitz strike, Hellcats were back in Norwegian skies, engaging in a unique dogfight with the Luftwaffe. On May 8 Emperor’s No. 800 Squadron escorted a shipping strike that was intercepted by fighters of Jagdgeschwader (Fighter Wing) 5. The British reported a mixed bag of Me-109Gs and Fw-190As. The Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf fighters were roughly as fast as the Grumman at sea level, but neither could turn with a Hellcat. Being lighter, with a lower power loading, the 109 possessed a climb advantage.

The Germans splashed one Hellcat on the first pass but the other Fleet Air Arm pilots used their superior maneuverability to claim two 109s and a 190. The latter was credited to Lieutenant Blyth Ritchie, a Scot with 3½ previous victories in Sea Hurricanes. In turn, the Germans erroneously claimed three Grummans, though a second Hellcat likely fell to flak. The Luftwaffe actually lost three Messerschmitts and pilots, as no Focke-Wulfs were downed.

The next day Emperor’s other Hellcat squadron, No. 804, splashed two Blohm & Voss Bv-138 flying boats. The skipper of 804 Squadron was the highly experienced Lt. Cmdr. Orr, with at least 8½ victories in Fairey Fulmars from his 1940-41 Mediterranean days.

On May 14 Emperor’s Hellcats pounced on a flock of Heinkel He-115 floatplanes off Rørvik. Ritchie, leading a No. 800 Squadron flight, easily shot one down, becoming one of only 14 Royal Navy aces. Then he rendezvoused with Orr and shared in the destruction of another Heinkel. At least two other He-115s were strafed on the water.

“By the time we had knocked our speed off and turned around to run in at them again, the three remaining floatplanes were bobbing up and down on the water like sitting ducks,” Orr related. “White Flight had since exhausted their ammunition after strafing the remaining He 115s, and it was left to us to finish them off. I shared in the sinking of one and then we set another alight. A No. 800 Squadron aircraft flown by Sub-Lieutenant Holloway was hit by return fire from one of the He 115s and the pilot was forced to bail out on the return trip to Emperor. Sadly, he was never found.”

Anvil-Dragoon was the second largest amphibious operation in Europe during World War II. Two and a half months after the Normandy landings, the troops participating in “D-day South” went ashore in the most glamorous venue of any military enterprise in the war: the French Riviera.

The initial landings were on August 15, between Toulon and Cannes. Among the seven British escort carriers supporting Dragoon was Emperor, still hosting the Hellcats of 800 Squadron. (The other Royal Navy flattops carried Wildcats and Supermarine Seafires.)

Hellcats possessed an inherent advantage over the Royal Navy’s Wildcats and Seafires. F6F-5s routinely carried more ordnance, lending greater versatility as fighter-bombers. For instance, the Seafire Mark III usually loaded four rockets versus the Hellcat’s six.

Two American Hellcat squadrons were aboard the escort carriers USS Tulagi and Kasaan Bay, each with 24 new F6F-5s. Tulagi carried Lt. Cmdr. William “Bush” Bringle’s Observation Fighter Squadron 1 (VOF-1), whose pilots specialized in spotting naval gunfire. Hard experience had shown the vulnerability of traditional spotter floatplanes to enemy fighters, so Bringle’s crew wore two hats as artillery observers and fighter pilots. They were equally adept at both tasks.

Bringle’s pilots had cut their teeth on the Vought F4U-1, as had Lt. Cmdr. Tom Blackburn’s VF-17 and Joe Clifton’s VF-12. “We loved the Corsair,” Bringle said, but the Navy, in a left-hand/right-hand mixup, did not fully appreciate that the three squadrons had largely cured the F4U’s notorious carrier-landing problems. Therefore, VOF-1 and VF-12 went to war in Hellcats.

Kasaan Bay carried VF-74 under Lt. Cmdr. Harry Bass, hurriedly deployed to meet the pressing need of Anvil-Dragoon. Though not specifically trained for fighter-bomber missions, Bass’ pilots would run up respectable records with bombs and rockets. The squadron also “beached” a night-fighter detachment on Corsica, providing nocturnal protection to the amphibious force.

D-day, August 15, dawned gray and misty, with both U.S. squadrons bombing German coastal defense guns. Subsequent missions were largely armed reconnaissance, attacking targets of opportunity with bombs, rockets and even impact-fuzed depth charges.

Neither VOF-1 nor VF-74 had trained for close air support, but they answered requests from the U.S. VI Corps when possible. Though the infantrymen described pinpoint targets, without an airman’s eye to direct the fighters it was almost impossible for aviators to identify the objective.

Enemy transportation networks were easier and more vulnerable targets. The Hellcats bombed rail lines and strafed roads crowded with German forces rushing southward to oppose the landings. To Lieutenant Fred Schauffler, a two-lane road resembled “5:00 o’clock traffic back home in Boston.”

The two “baby flattops” logged 100 sorties that day, without loss. One Kasaan Bay Hellcat suffered flak damage that prevented lowering its tailhook, so the pilot recovered ashore on Corsica.

D-plus-2 was tougher. Searching for likely targets on the 17th, a pair of VF-74 pilots disappeared overland in poor weather.

“We usually flew with six rockets, and sometimes one or two bombs,” Bringle recalled. “We had a time over target on gunfire spotting, and between times we’d often look for something to bomb and strafe.”

During the first four days the Hellcats saw no Luftwaffe airplanes. Then, on the morning of August 19, some VOF-1 pilots glimpsed three He-111s 50 miles northwest of Marseilles but lacked fuel to pursue. However, later that afternoon Bringle’s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. John Sandor, flushed a pair of Heinkels 125 miles inland, south of Lyon. The He-111s split up, with Sandor and his wingman chasing one down to 700 feet. He and Ensign David Robinson attacked from starboard, scoring good hits, and the bomber crash-landed. Some of the German crewmen were killed as the Americans made a strafing pass.

Meanwhile, the second section had reeled in the other Heinkel. Lieutenant Rene Poucel and Ensign Alfred Wood shot it down from astern, sending it crashing into the same region where Poucel’s parents had been born.

Scouting farther afield, Wood came across another Heinkel, fired from 6 o’clock and flamed both engines. Sandor and his three pilots also claimed 21 trucks and wrecked a locomotive before trapping aboard Tulagi.

Fighting 74 also carved some notches on the 19th. Patrolling the Rhône River, Bass’ division downed a Junkers Ju-88 that morning. Later, two Kasaan Bay divisions jumped a Dornier Do-217. Six of the eight pilots attacked but only two scored: Lieutenant (j.g.) Edwin Castenado and Ensign Charles Hullard shared the credit. It made Castenado the squadron’s top scorer, with a quarter of the Ju-88 and half of the Do-217.

At sundown on D-plus-4 the naval aviators could take satisfaction in having performed well in a variety of missions. But August 20 turned sour: Bass’ Hellcat was hit by flak while strafing northwest of Lyon and he fatally crashed.

Bringle’s squadron lost two planes. Lieutenant David Crockett was spotting gunfire over Toulon Harbor when he was forced to bail out. The Germans nabbed him and he endured four days of captivity before the city surrendered. Lieutenant James Alston’s plane was subsequently hit while strafing. He zoomed up to 5,000 feet and jumped as one wing failed. He was reported safe that same day.

More aerial encounters occurred on the 21st, again involving Tulagi pilots. Lieutenant (j.g.) Edward Olszewski’s and Ensign Richard Yentzer’s F6Fs had taken flak damage but they continued the mission, discovering three Junkers Ju-52/3m transports northbound from Marseilles. Olszewski selected the nearest in the formation and destroyed it in two passes. Then, with only one .50-caliber still firing, he dropped the second trimotor. Yentzer made three gunnery runs to flame the lead aircraft.

That day VOF-1 sustained another loss when Lieutenant (j.g.) John Coyne’s Hellcat came apart while diving on a truck convoy. He went over the side barely in time to open his parachute but landed safely.

On the evening of D-plus-6 the American carriers pulled back for two days of replenishment. Meanwhile, British No. 800 Squadron kept a Hellcat presence over southern France, but lost three aircraft, probably all to flak.

With Tulagi and Kasaan Bay back on the line, the Dragoon operation continued for another week. From August 24 to 29, two more VOF-1 Grummans were lost in water landings, including that of squadron CO Bringle. He and another pilot were rescued.

Flying for 13 days, the two American squadrons wrote off 11 F6Fs of the 48 assigned. Fighting 74 lost four pilots and VOF-1 two. But between them they were credited with downing eight German aircraft, destroying some 800 vehicles and wrecking or immobilizing 84 locomotives.

A tribute to the Grummans’ effectiveness came from Rear Adm. Thomas Troubridge, the British commander of the Allied carrier force. He singled out the F6Fs in his after-action report, noting, “The U.S. aircraft, especially the Hellcats, proved their superiority.”

Meanwhile, Bush Bringle’s crew got on with the war. Redesignated as a composite squadron (VOC-1), the naval aviators became globetrotters, flying FM-2 “Wilder Wildcats” from escort carriers in the Pacific. Gunfire-spotting skills were so highly valued that VOC-1 probably logged more hours per pilot than any Pacific carrier squadron during 1945. In addition to the two Ju-52s he had downed over France, Ed Olszewski claimed a Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bomber off Okinawa to become one of probably three U.S. Navy pilots with German and Japanese planes to his credit.

For Grumman’s hardy Hellcat, World War II truly was a global conflict.

The Royal Air Force’s Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down evaluated a wide variety of Allied and German aircraft during the war. Based on those comparisons, the Grumman Hellcat and Messerschmitt Me-109G were evenly matched for top speed at sea level (305 mph), though the “Gustav” gained 20 mph minus its drop tank. Hellcats nearly always flew with a 150-gallon external tank. Top speed was very close for both fighters at 22,000 feet: 375 vs. 367, slightly favoring the Grumman, but the Messerschmitt pulled ahead at 395 mph clean. In a turning fight the 109 could not compete with the Hellcat, whose 36 pounds per square foot wing loading trumped the Messerschmitt’s 42. But vertical performance gave the 109 a decided advantage, with a power loading of 4.9 pounds per square foot versus 6.1 for the Grumman. Those figures translated to average climb rates of 3,400 feet per minute for the 109 and 2,500 for the Hellcat. However, the Luftwaffe pilot would have to fly a fairly precise vertical profile to negate the Grumman’s superior maneuverability. Grumman worked hard on cockpit geometry and design, giving the F6F pilot far better visibility than the Messerschmitt provided. Hellcats certainly packed a more lethal punch: six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns versus the 109’s typical battery of a 20mm cannon and two 13mm guns, all in the nose. Finally, the rugged Grumman airframe and legendary Pratt & Whitney radial translated to better survivability than afforded by the lighter 109’s inline Daimler-Benz. Comparing the F6F-3 to the Focke-Wulf Fw-190A, British test pilots found them well matched. Legendary Royal Navy pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown noted: “The German had a speed advantage; the American had a slight advantage in climb. Both were maneuverable and had heavy firepower. “Verdict: this was a contest so finely balanced that the skill of the pilot would probably be the deciding factor. “So—the Hellcat and Corsair (not mentioned here, but generally a bit better than the Hellcat) would hold their own in the air over Germany.”

Barrett Tillman is the award-winning author of nearly 800 articles and more than 40 books, including Hellcat: The F6F in World War II and On Wave and Wing: The 100-Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft Carrier, which are recommended for further reading.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe click here!

Are you ready to build Olszewski and Wood’s F6F-5? Click here!