ON JULY 2, 1812, the schooner Cuyahoga, a private American vessel, sailed from Lake Erie into the mouth of the Detroit River and past Fort Amherstburg, a British stronghold on the Canadian side of the river. Unknown to those on board, the United States had formally declared war against Great Britain. But the British at Amherstburg knew. They seized the ship from the surprised crew and were rewarded with papers belonging to American brigadier general William Hull. Among them: correspondence outlining an invasion of Canada.

The scene at Fort Detroit was ‘like the entrance to hell’

It was quite a coup. Days into the War of 1812, British held the plans for a key American strike, complete with troop strength and insights into the enemy commander’s state of mind. Armed with these secrets, the redcoats over the next few weeks would turn the tables on the Americans, launch their own invasion, and force the only surrender of a U.S. city to a foreign army.

When American leaders declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812, they described it as a second fight for liberty. The country was outraged by the impressment of U.S. sailors into Royal Navy service, not to mention British collusion with Indians to block American expansion in frontier territories such as Michigan and Indiana. But Americans also coveted the rich farmland of British-held territories to the north. “The conquest of Canada is in your power,” Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky had crowed to his colleagues in February 1810, boasting that his state’s militia alone was enough “to place Montreal and Upper Canada at your feet.”

At the war’s start, American invasion plans had called for three thrusts, two from New York and a third from Michigan targeting the province of Upper Canada, what is now Ontario. But that strategy was more feasible in theory than in practice. The U.S. Army had just 6,750 soldiers. Anywhere from 500,000 to 700,000 militiamen could be called to arms, but many, perhaps most, were poorly trained. Nor could they be counted on to take up arms; some, particularly those in the Northeast living peaceably with their neighbors across the border, claimed the Constitution obliged them to fight only in defense of their home states.

The invasion was also handicapped by its leaders. The U.S. Army’s two major generals and nine brigadier generals were Revolutionary War veterans, most owing their ranks to politics or seniority.

The 59-year-old William Hull, author of the letters on the Cuyahoga, was a case in point. Born in Connecticut and educated at Yale, Hull had served with distinction during the Revolutionary War, rising from militia captain to lieutenant colonel. Appointed governor of the Michigan Territory in 1805, Hull had secured southeastern Michigan for American settlement, handling the negotiations of the Treaty of Detroit with various Indian tribes.

In April 1812, as war with Britain loomed, President James Madison and Secretary of War William Eustis gave Hull command of the North-Western Army. But the general no longer cut an impressive military figure. Thanks to a stroke suffered the year before, he slurred his speech and occasionally drooled. And, as his men would learn, he was overly fond of drink.

Nonetheless, in June, Eustis dispatched troops of the 4th U.S. Infantry Regiment and three Ohio regiments totaling 1,200 militiamen to Hull for the proposed invasion of Upper Canada. Hull had doubts that such an undertaking could succeed without naval control of Lake Erie, but he moved his army north from Ohio to Detroit to prepare for the strike. It was an arduous march through swamps. The men bickered, and morale slipped. When the force reached Lake Erie, Hull, hoping to speed things along, hired the ill-fated Cuyahoga to ferry supplies to Detroit—including his personal papers, which documented not only the invasion plans but also the wrangling in his ranks. Only the next day did he receive word from Washington that the war had begun.

HULL’S ARMY REACHED DETROIT in late June. The orders to launch the invasion arrived July 9. Three days later, he crossed the Detroit River into Canada with 400 regulars and 800 militiamen and occupied Sandwich (now Windsor, Ontario) unopposed. Issuing a proclamation that portrayed him as a liberator, the general assured protection for Canadians but promised to bring “the horrors and calamities of war” to those who resisted him.

Though Hull had so far persuaded most of the Indian tribes to stay out of the fight, he warned: “[If] the savages are let loose to murder our Citizens and butcher our women and children, this war will be a war of extermination.” He added that no white man fighting by the side of an Indian would be taken prisoner. “Instant destruction will be his lot.”

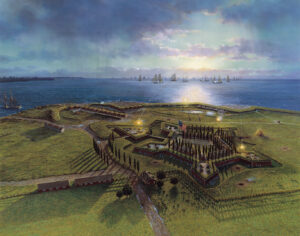

Thirty miles south of Sandwich lay Amherstburg, a prize ripe for the taking. American forces outnumbered the British by roughly two to one. Hull could have easily taken the fort if he had been swift and decisive. But he was neither; he chose to delay any advance until 24-pounder guns and heavy mortars arrived to reduce Amherstburg’s defenses. “Instead of having an energetic commander, we have a weak old man,” complained Colonel Lewis Cass of the Ohio militia.

Hull’s forces did manage to inflict the war’s first casualties on the British; on July 16, a probe sent from Sandwich traded shots with British guards on the road to Amherstburg, mortally wounding James Hancock of the 41st Regiment of Foot and capturing John Dean, a badly wounded soldier. But for the better part of a month, Hull would wait, the invasion on hold.

MAJOR GENERAL ISAAC BROCK, chief administrator of Upper Canada, was charged with stopping Hull. From his headquarters at Niagara-on-the-Lake, a couple hundred miles east of Detroit, Brock could see that his situation was tenuous. The British in Canada had only a small nucleus of regulars, with the defense of Upper Canada assigned to 300 redcoats of the 41st Foot, a detachment of Royal Artillery, and Royal Newfoundland Fencibles. These troops were supplemented by provincial militia, but inconsistent pay and concern for their farms made them unreliable and even mutinous. Nor was Brock sure that the Indians, longtime allies of the British, would join the fight.

But Brock, a 43-year-old Napoleonic War veteran, was by nature a man of action—the polar opposite of Hull. While his superiors urged him to take a defensive approach, the general wanted to go on the offensive. “Most of the people have lost all confidence,” he reported. “I however speak loud and look big.”

Soon after the war’s start, Brock had set in motion an assault on the American fort on Mackinac Island, a strategic post hundreds of miles to the north that guarded the strait between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. On July 17, a force of 45 redcoats, 150 fur traders, and 400 Indians recruited from several tribes seized Fort Mackinac almost effortlessly from an American garrison still unaware that war had begun. The victory gave the British a new forward base, but more important, it persuaded the Wyandot tribe to commit to fighting with the British.

Now, with Hull threatening Amherstburg, Brock wasn’t about to back down. In a proclamation of his own, he condemned the Americans’ “unprovoked declaration of War” and called on Upper Canada’s freeholders to keep their oath to king and country. Courting the Indians, he defended the right of the “brave bands of natives” to join the battle. While Hull had referred to the Indians as “savages,” his British counterpart pointedly argued: “They are men, and have equal rights with all other men to defend themselves and their property.”

Brock also went before Upper Canada’s General Assembly and obtained authorization to declare martial law and the funds to pay the militia. On August 6, he set out by boat on Lake Erie, heading west toward Amherstburg with 250 militiamen and 50 soldiers of the 41st.

Hull, meanwhile, continued to dither. Fort Mackinac’s defeated and paroled garrison arrived in Detroit by schooner on August 2, giving Hull more reason to pause. The loss, he wrote to Washington, “opened the northern hive of Indians and they were swarming down in every direction.” Though Cass and other officers in the Ohio militia urged him to advance, he instead pleaded for more supplies.

Even this decision backfired. With the supply train en route, he sent 200 Ohio militiamen to escort it to Detroit. Three miles north of the Wyandot village of Brownstown, the detachment was ambushed by 24 Indians, including Wyandots and the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. The men panicked and fled, and when the Indians finally broke off their pursuit, 18 Ohioans were dead, 12 wounded, and 70 missing.

That was August 5. Hull announced the same day that he would assault Amherstburg, but he quickly changed his mind when he learned that General Brock was coming west. And on August 8, Hull, abandoning the eagerly anticipated invasion, began a withdrawal to the American side of the Detroit River. He even proposed giving up Detroit and falling back to the south, closer to supply bases and reinforcements, but the Ohio militia officers rejected that idea.

Although Hull’s invasion of Canada was essentially over, he did manage to score one more victory, albeit in Michigan. As his forces pulled back to Detroit, he sent another party to escort the expected supply train. On August 9, the 280 regulars and 330 Ohio militia led by Lieutenant Colonel James Miller were confronted south of Detroit near the village of Maguaga by 150 soldiers of the 41st Regiment and Canadian militiamen, as well as 65 Potawatomis. Things went badly for the redcoats. Well drilled but lacking combat experience, they mistook movement in the woods as an American flanking attempt and traded shots with their Indian allies. Though their commander ordered a charge, the men misinterpreted a bugle call and retreated.

This left the Americans tactical victors of the war’s first pitched land battle. But Miller, worried about an Indian ambush and uncertain of what lay ahead, held his troops in place for two days, then retired to Detroit.

ON AUGUST 13, General Brock and his reinforcements arrived at Fort Amherstburg. Meeting Tecumseh, he was impressed by the Shawnee leader, noting that “a more sagacious or a gallant warrior does not, I believe, exist.” For his part, Tecumseh gestured toward Brock and exclaimed to his braves, “This is a man!”

Tecumseh showed Brock correspondence recovered after the Brownstown skirmish which, added to the Cuyahoga papers, confirmed Brock’s suspicions that Hull was a shaky commander leading an army riven with dissension. On the morning of August 15, Brock led 300 regulars and 400 militia out of Amherstburg while Royal Engineers established a battery of three guns and two mortars on the river bank opposite Detroit. Brock then sent Hull a message demanding surrender and warning: “It is far from my inclination to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops will be beyond control the moment the contest commences.” When Hull refused, the British artillery began to bombard the fort.

Hull was not eager for this fight. Some of his Michigan militia had deserted, and he had discovered that Cass and others in the Ohio militia were conspiring to remove him from command. Rather than confront them and risk a mutiny, he had sent 350 of the Ohioans south to meet another supply train. Terrified of what the Indians might do to Detroit’s civilian residents—including his daughter and her children—he moved all the women and children to a root cellar in an orchard.

On the night of August 15–16, about 600 Indians led by Tecumseh crossed the river and began circling Fort Detroit, weaving in and out of the wood line to make their force appear bigger. On the morning of the 16th, Brock landed south of Detroit at the town of Spring Wells with more than 700 troops—including some 300 militia wearing cast-off red tunics to look like regulars of the 41st. Hull, to his credit, had foreseen this move. He had stationed Captain Josiah Snelling Jr. at Spring Wells with an artillery piece and orders to withdraw only if compelled by overwhelming force. Snelling, however, had unaccountably withdrawn, and Brock landed unopposed.

The British had hoped to cut Detroit off from its supply route and draw out Hull’s troops for a battle outside the fort. But when his scouts reported the Ohio militiamen to the south—the men Hull had sent out to escort the supply train—Brock decided to clinch the issue much sooner. Leading his troops to the fort, he lined them up with double the normal spacing to suggest a larger force. The Indian warriors were painted for war and made for a frightening sight. It was “like the entrance to Hell,” wrote one observer, “with the gates thrown open to let the damned out for an hour’s recreation on earth.”

When Brock and his troops arrived at the fort’s gate, they found it guarded by two 24-pounder cannons. But to the gunners’ chagrin, Hull ordered them to hold their fire. All this time, the general had been stewing away in a shelter, safe from fire. Officers later said he was drinking heavily. He certainly overestimated the British and Indian numbers; counting the Ohioans at the British rear, he still commanded nearly double the 1,330 men that Brock had.

Regardless, he had a white tablecloth raised as a sign of truce and sent officers out to “accept the best terms which could be obtained.” After an hour of parley, Hull surrendered Detroit and the 2,188 men of his command, as well as 39 carriage guns, 15 wall-mounted cannons, 2,500 muskets, and 500 rifles with shot, powder, and flints. Money, furs, and other booty valued at $200,000 were distributed among the victors.

HAVING ACHIEVED IN FOUR DAYS what Hull had failed to do in a month, Brock paroled the 1,600 militiamen. Hull and his 582 regulars were marched east to Quebec City. Brock, knighted for his achievement, did not have long to savor the victory: The audacity that brought him triumph in Detroit would earn him a bullet through the heart as he led a charge at the October 13 Battle of Queenston Heights, near Niagara Falls.

Eventually paroled, William Hull returned to disgrace. Arguing that he had surrendered to spare the women and children from a brutal Indian massacre, he petitioned for a court-martial, hoping to clear his name. But blame for the disaster had already settled on his shoulders. When convened on January 3, 1814, the trial proved a case of “careful what you wish for,” as Hull was charged with treason, cowardice, neglect of duty, and unofficerlike conduct. Denounced by his officers in their testimony, he was convicted on all the charges except treason, which the court dropped as being outside its jurisdiction. Indeed, the case against Hull was so overwhelming that he was sentenced to death—the only time in American history a general has faced the death penalty. Hull was spared only when President Madison, while endorsing the court’s sentence, stayed his execution. Over the next 10 years Hull wrote two books to explain his actions. He died in Newton, Massachusetts, on November 29, 1825.

An ironic twist of history saved the Hull name from being forever associated solely with bungled battles in the War of 1812. Just three days after William Hull’s capitulation at Detroit, his nephew Captain Isaac Hull led the frigate Constitution to a resounding victory over the British frigate Guerrière in a signature triumph for the fledgling U.S. Navy.

Jon Guttman is the research director for MHQ and other World History Group publications as well as the author of Defiance at Sea and more than 25 books on military aviation history.