The stock market had been falling for a month, slowly at first, then faster. On Friday, October 18, 1929, the decline hastened in heavy trading. On Monday, prices fell again. On Tuesday, they rose a bit, only to plummet on Wednesday. On the morning of Thursday, October 24—the day dubbed “Black Thursday”—prices tumbled so fast that spectators in the gallery began to weep.

At 1:30 that afternoon, Richard Whitney, acting president of the New York Stock Exchange, appeared on the trading floor and strode briskly to Post Number 2, where stocks in U.S. Steel were traded. Tall and distinguished, Whitney stood silent for a moment, with a golden pig—the symbol of his Harvard dining club—dangling from the watch chain encircling his prosperous paunch. He had just convened a meeting of the nation’s most powerful bankers, who agreed to put up $20 million to stop the sell-off and stabilize prices. The room fell silent as traders strained to hear what Whitney would say.

He asked the price of U.S. Steel’s stock and was informed that it had fallen below $200 a share. “I bid 205 for 10,000 Steel,” he responded.

Then he moved to other posts and paid generous prices for other blue-chip stocks. It worked: the market rallied and Whitney became a hero. “Richard Whitney Halts Stock Panic,” read one headline, and tabloids dubbed him the “White Knight of Wall Street.”

The rally didn’t last long—the market crashed five days later, leading to the Great Depression—but Whitney’s fame endured. He served five years as president of the New York Stock Exchange, and became a symbol of America’s old-money, blue-blood elite—first for his coolness in crisis, then for his arrogance and corruption.

He was born in Boston in 1888, to a family that had arrived in Massachusetts in 1630. His father was a bank president. His uncle and his brother were executives in J.P. Morgan’s financial empire. At Groton, Whitney was captain of the baseball team. At Harvard he rowed on the varsity crew. He married a rich woman and started his own brokerage firm—Richard Whitney & Co.—which, thanks to his connections, became the official broker for the House of Morgan. He bought a five-story townhouse on East 73rd Street in Manhattan and a 495-acre estate in New Jersey, where he raised thoroughbred horses and served as Master of Fox Hounds for the Essex Hunt.

As president of the Stock Exchange during the early 1930s, Whitney found himself battling another graduate of both Groton and Harvard—President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When FDR backed a bill to create the Securities and Exchange Commission to regulate the stock market, Whitney led the battle against it. The regulations were a “menace to national recovery,” he said, and if they were adopted, “grass will grow on Wall Street.” There’s no need for government regulation, he insisted: “The exchange is a perfect institution.”

Whitney’s lobbying failed to convince Congress, which passed the bill creating the S.E.C. Then Roosevelt appointed Joseph P. Kennedy—a savvy former stock manipulator himself—as S.E.C chairman, reasoning that Kennedy knew all the dirty tricks of the trade and could therefore crack down on them.

Whitney detested Kennedy as a traitor to the exchange but he admired Kennedy’s financial wizardry. When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, Kennedy made a fortune importing Haig & Haig Scotch and Gordon’s Gin. Inspired, Whitney decided to get into the booze business. He founded the Distilled Liquors Corporation and began producing an applejack called Jersey Lightning. It failed to catch on. He imported 106,000 gallons of Canadian rye whiskey, but that didn’t sell either. When Distilled Liquors’ stock plummeted, Whitney tried to boost the price by borrowing millions to buy more shares. It didn’t work. Apparently, nobody wanted his booze or his stock. Desperate, Whitney borrowed more money from his wealthy friends to finance various get-rich-quick schemes. But they, too, failed.

So “the White Knight of Wall Street,” started stealing.

Whitney’s first theft was $150,200 in bonds belonging to the New York Yacht Club, for which he served as treasurer. But that wasn’t enough to save his crumbling empire, so he stole from his brokerage firm’s customers—Harvard University, St Paul’s School, his father-in-law’s estate, his wife’s trust fund. And he embezzled more than $1 million from the New York Stock Exchange’s Gratuity Fund. That fund paid benefits to the families of deceased members of the Exchange, so Whitney’s theft, wrote Wall Street historian John Steele Gordon, “amounted, almost literally, to stealing from widows and orphans.”

Inevitably, Whitney’s schemes collapsed. Rumors spread on the street that his company was failing. Officials of the exchange investigated and discovered that Whitney was embezzling from his customers. Undaunted and arrogant, Whitney tried to convince Charles Gay, his successor as president of the exchange, to cover up his crimes.

“I am Richard Whitney,” he told Gay. “I mean the stock exchange to millions of people. The exchange can’t afford to let me go under.”

In Whitney’s heyday, the exchange’s old-boy network might have protected him. But, as Gay understood, in the new era of S.E.C watchdogs, that was no longer an option. So, on the morning of May 7, 1938, Gay announced to the exchange that Whitney and his company were suspended for “conduct contrary to just and equitable principles of trade.”

“Not Dick Whitney!” President Roosevelt said when aides told him the shocking news about his fellow Groton grad. “Dick Whitney—I can’t believe it.”

“Wall Street could hardly have been more embarrassed,” The Nation magazine noted, “if

J.P. Morgan had been caught helping himself from the collection plate at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.”

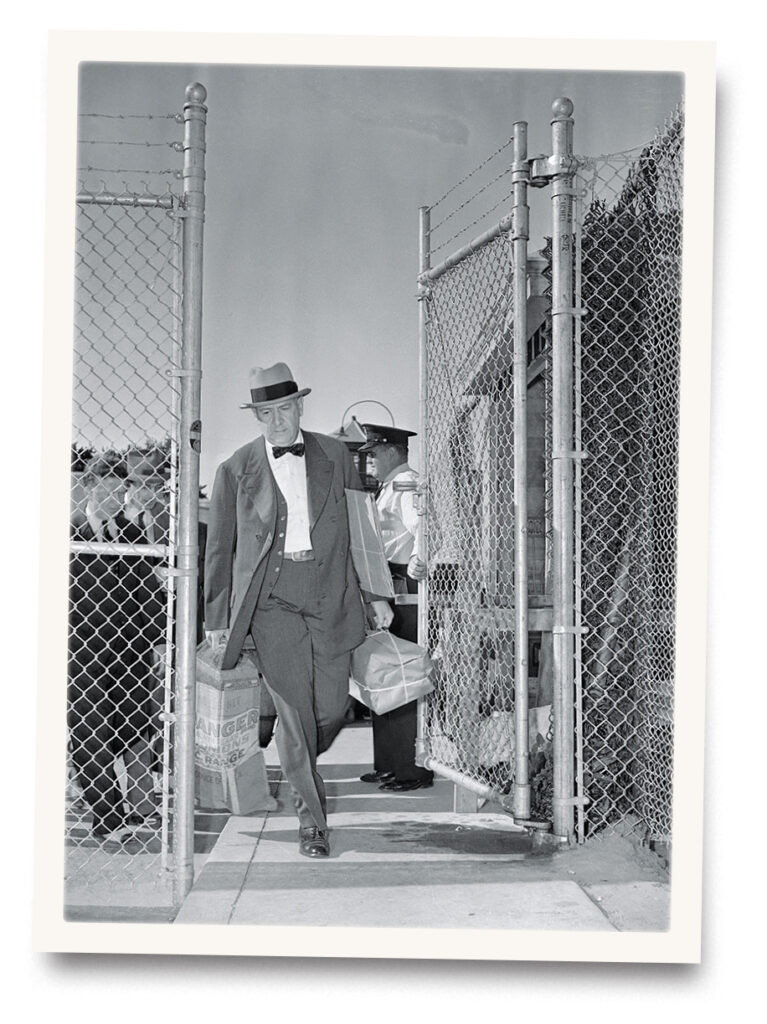

Indicted for fraud and embezzlement, Whitney pled guilty and was sentenced to 5–10 years in prison. The next day, a crowd packed Grand Central Station to gawk as cops loaded five handcuffed prisoners onto a train bound for Sing Sing Prison—a rapist, two extortionists, a holdup man, and the former president of the New York Stock Exchange.

Whitney served three years and four months before he was paroled in 1941. Barred from the securities business, he managed a family-owned dairy farm in Massachusetts. His wife took him back and his brother repaid every dollar Whitney had stolen.

When he died in 1974, at age 86, his obituary in The New York Times noted the irony that Whitney’s shocking scandal had led to the enactment of the regulations he had fought so hard against: “It hastened the adoption of drastic reforms governing stock market dealings, long pressed by the Securities and Exchange Commission and resisted by an old-guard clique on the Street whose powerful leader had been Mr. Whitney himself.”

This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.