Donald Trump launched his third campaign for the White House amid a blizzard of legal investigations. In New York City, he was indicted for falsifying business records to conceal hush money payments to porn star Stormy Daniels. He was also slapped with two civil lawsuits: one for fraudulently overvaluing his assets; a second for defaming advice columnist E. Jean Carroll when he denounced her belated claim that he had raped her in 1996.

In Georgia, a grand jury pondered whether he had violated state election laws by fielding a slate of bogus Trump electors after Joe Biden won the state en route to the presidency in 2020, or by pressuring Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger to “find” the votes he needed for him to win it. The FBI wanted to know why documents labeled “Top Secret” had been squirreled away at his Palm Beach home Mar-a-Lago, while Justice Department special counsel Jack Smith grilled a raft of witnesses to his alleged attempts (not just in Georgia) to overturn his 2020 loss. Smith’s bag included his veep Mike Pence.

Donald Trump likes to define himself in superlatives: biggest, richest, best. But he is not the first politician to seek office under a legal cloud. For example, James Michael Curley, four-time Boston mayor and all-time symbol of the big city Democratic pol, got an early boost from a jail sentence. Curley was the son of poor Irish Catholic immigrants. Throughout his long career, he pitched himself as the champion of his ethno-religious clan and class of origin, steering gifts, jobs and public works to friends and followers (and kickbacks to himself). He proclaimed his good intentions in a rich, rolling voice that one drama critic compared to actress Tallulah Bankhead’s.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Curley won elections to the lower houses of the Boston and Massachusetts legislatures. But in October 1902 he pushed the politics of generosity too far: he took a civil service exam for a would-be letter carrier who doubted he could pass it himself. In September 1903, the impersonator was convicted in federal district court of “conspiring…to defraud the United States,” and sentenced to two months in prison. Nothing daunted, Curley turned the verdict into a campaign slogan. He ran for the Board of Aldermen, the upper house of the Boston legislature, that November, boasting of his bogus test-taking: “[H]e did it for a friend.” Curley was elected and, after his appeals had been exhausted, re-elected in November 1904 while serving his time in the Charles Street jail. “I read…every book in the jail library,” he recalled, “and I made a lot of new friends among the authors.” His flesh and blood friends propelled him, over the following decade, to the U.S. House of Representatives, and his first term as mayor of Boston.

Another jail house office seeker was Eugene V. Debs, whose fifth presidential race was run behind bars.

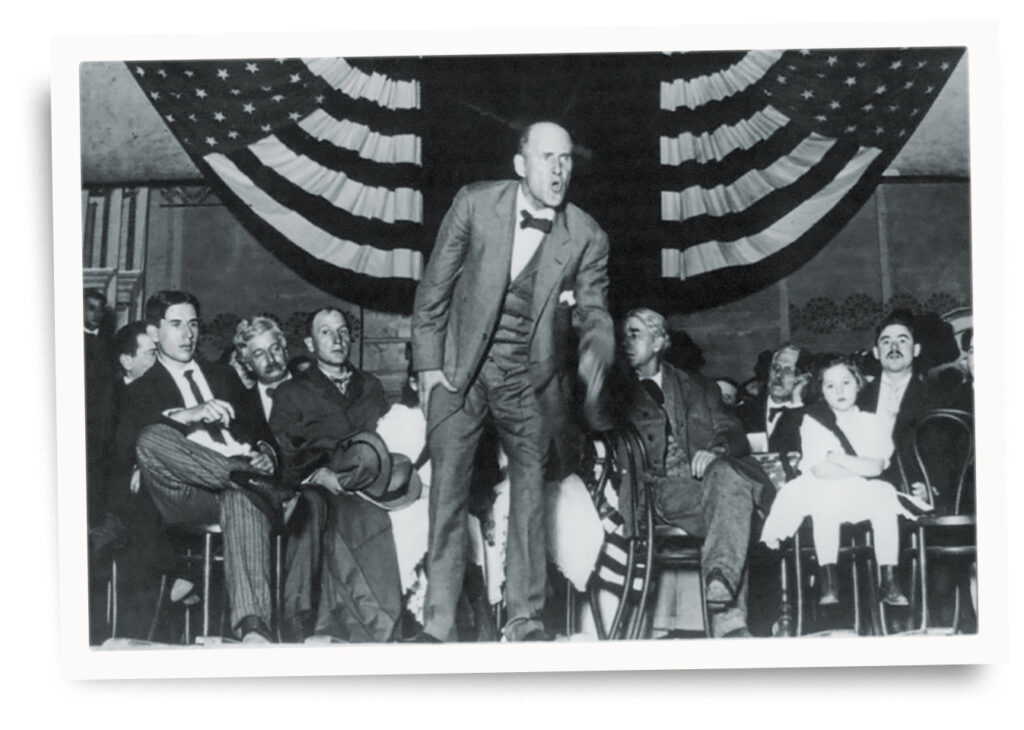

Debs’ parents, immigrants to Terre Haute, Ind., from Alsace, named him after French novelists Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo. But Debs’ political idols were all-American: Tom Paine, John Brown, Abraham Lincoln. As a teenager he worked as a fireman, or stoker, on train engines; as an adult he became a labor journalist, a union organizer, and the perennial presidential candidate of the fledgling Socialist Party. Debs ran four times from 1900 to 1912, barnstorming the country.

One listener described the effect of his oratory. “When Debs says ‘comrade’ it is all right. He means it. That old man with the burning eyes actually believes that there can be such a thing as the brotherhood of man….As long as he’s around I believe it myself.” In the 1912 free for all between Woodrow Wilson (D), Theodore Roosevelt (Bull Moose) and William Howard Taft (R), Debs polled 900,000 votes for a respectable six percent.

The overriding issue of the decade became the World War (it was not yet called I). True to socialism’s international spirit, Debs deplored America’s entry: “the master class has always declared the wars; the subject class has always fought the battles.” After a speech in Canton, Ohio, he was arrested for encouraging resistance to the draft and sentenced to ten years in prison. Debs’ concluding speech to the court was radical poetry. “While there is a lower class I am in it; while there is a criminal element I am of it; while there is a soul in prison I am not free.” Debs was imprisoned first in Moundville, West Virginia, then in Atlanta. So it was that he ran his last presidential race from the slammer. “It will be much less tiresome,” he joked, “and my managers and opponents can always locate me.”

Although Debs had the sympathy of non-socialists who thought him ill-treated, he polled barely more than he had in 1912, while his percentage of a popular vote broadened by women’s suffrage fell to 3 percent. Americans were tired of causes, foreign and domestic. New president Warren Harding commuted Debs’ sentence to time served on Christmas 1921.

James Michael Curley, after four decades in and out of office in Massachusetts, had a second stint in jail. This time the crime was mail fraud. During World War II, Curley fronted a firm that claimed to help small businessmen get defense contracts, while in fact it only helped itself to its clients’ retainers. Curley, indicted in September 1943, did not go to trial until November 1945. Late in the interim he was elected to his fourth term as mayor of Boston. “Curley gets things done!” was the winning slogan.

Twelve days after his inauguration in January 1946, a jury in federal district court in Washington, D.C. found him guilty. He appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, but in June 1947 the septuagenarian mayor was taken to Danbury, Conn., to serve a six month sentence. He kept up a brave front. “The guests at this hotel,” he wrote of his fellow inmates, “give me cigars, oranges and razor blades….I am fortunate to have friends everywhere I go.” But the prisoner suffered from diabetes and a heart condition. President Harry Truman knocked a month off his time at Thanksgiving. The recidivist returned to City Hall.

Politicians in humiliating circumstances can retain the loyalty of their supporters, and even win elections, for a variety of reasons. Debs and Curley both spoke for the aggrieved—burdened workers, snubbed ethnics. Their personalities, however different, conferred an aura upon them: Debs the idealist, Curley (in biographer Jack Beatty’s epithet) the rascal king. They were stars. But they sought stardom—or seemed to seek it—in the service of others. The others rewarded them with their votes.

Debs ran no more races after he got out of jail. He died in 1926, age 70, appealing for the convicted anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti. Curley ran for a fifth term as mayor, unsuccessfully, but won something more important: a fictionalized, and sanitized, account of his life as Frank Skeffington in Edwin O’Connor’s best seller The Last Hurrah. His favorite part, he told the author, was “where I die.” He died in 1958, age 83.

At least one of Donald Trump’s legal cases will never land him in jail. In May the jury in E. Jean Carroll’s civil suit found Trump liable for sexual abuse and defamation. If their verdict survives appeal, Trump will only be out monetary damages. Even hard time might not end his political career. You can be in the government and a guest of the government at the same time.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.