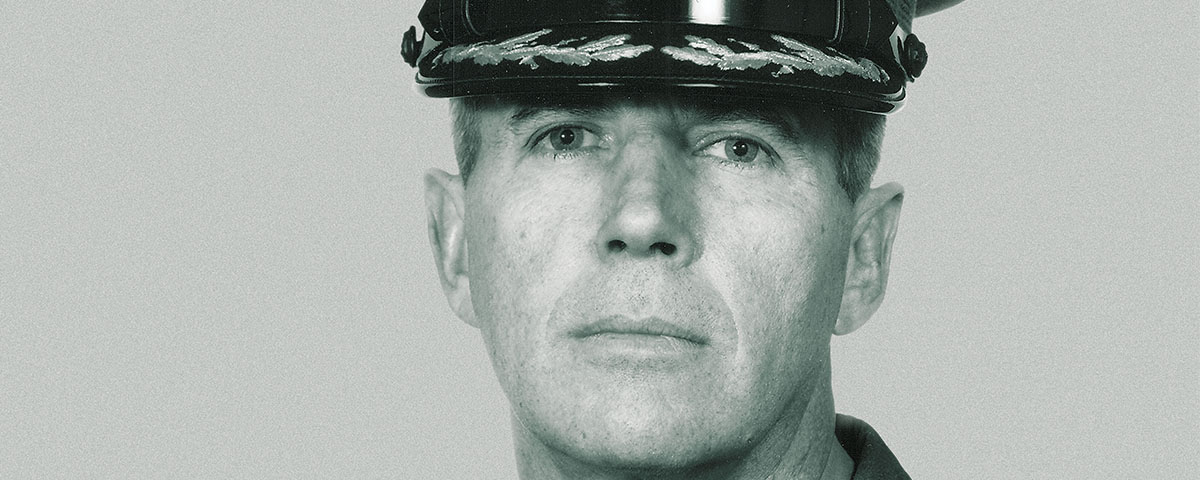

Capt. John Ripley was an adviser with the 3rd Battalion of the Republic of Vietnam Marine Corps on March 30, 1972, when the North Vietnamese launched its Easter offensive with a sustained artillery barrage. There was no sleep that night, as word came NVA troops supported by some 200 tanks were headed south toward the bridge over the Cua Viet River just north of Dong Ha.

In the morning the 3rd Battalion moved closer to the bridge to check the NVA onslaught. But it could not hold against the estimated 20,000 enemy soldiers. The bridge had to be blown, and Ripley—who had trained with explosives at the U.S. Army Ranger School—got his chance on April 2, Easter Sunday.

Under heavy fire he and fellow adviser Maj. Jim Smock dashed down the riverbank beneath the bridge, where engineers had stacked crates of TNT and satchel charges of C4 plastic explosive. A chain-link fence topped with razor wire pressed against the underside of the bridge. While Smock pulled down on the wire, Ripley slung two satchel charges over his back, climbed the fence, grabbed the bottom flanges of the downstream I-beam, swung his feet up and inched his way over the fence, badly lacerating his legs in the effort.

With 90 feet to go to the first bridge pier, Ripley let his feet hang free and hand-walked down the I-beam, three stories above the river. Arriving at the pier, he heaved himself up into the channel between the first two I-beams and rested a moment. After positioning the satchel charges, he crawled facedown on elbows and knees atop the I-beam flanges back to the fence, where Smock manhandled two more satchel charges and two boxes of TNT over the razor wire. Ripley placed the boxes atop the flanges and inched backward on elbows and knees, dragging the 180-pound load back out to the pier, where he placed the charges. Knowing he would need to place charges in the four remaining channels, he dropped down, hung by his hands, then swung free and grabbed for the next upstream I-beam.

Whenever Ripley swung into view beneath the I-beams, the NVA troops fired at him. Regardless, over the next two hours the Marine worked his way back and forth in the four remaining channels, placing some 500 pounds of explosives in all. When finished, he maneuvered back over the razor wire, dropped to the ground and caught his breath before clambering back out to rig the primer cord and detonators. But Smock and Ripley couldn’t find the crimpers needed to attach the detonators to the primer cord.

That left only one alternative.

Ripley, researcher John Grider Miller wrote, “had to bite down on the blasting caps to attach them to the fuzes. If he bit too low on the blasting cap, it could come loose; if he bit too high, it could blow his head apart.”

Ripley carefully crimped the detonators, then inched over the wire to hand-walk down the I-beam. Firing broke out immediately from the north bank. One low-angle tank shell bounced off the bridge and exploded on the south bank, setting up a vicious vibration that almost broke Ripley’s grip. He muscled through to attach the detonators, light the fuze and inch his way back to the south bank—albeit at a faster clip.

Meanwhile, Smock had found electrical detonators. A perfectionist, Ripley shimmied out one more time to set those as backup detonators, while Smock rigged an adjacent railroad trestle with TNT. Under covering fire from the Vietnamese Marines, Ripley and Smock then dashed back up the riverbank, playing out electrical cord as they went. Minutes later both spans blew.

For his heroism at Dong Ha Bridge Ripley received the Navy Cross. He later became the first Marine inducted into the U.S. Army Ranger Hall of Fame. Ripley died at 69 in 2008 and was buried with full military honors at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md.