On April 4, 1866, nearly a year after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Russian Czar Alexander II narrowly escaped a similar fate. Within a few weeks, the U.S. Congress adopted a joint resolution expressing its “deep regret of the attempt made upon the life of the Emperor of Russia by an enemy of emancipation.” At Congress’ request, President Andrew Johnson dispatched a special envoy—Assistant Navy Secretary Gustavus Fox—to hand-deliver the resolution to Alexander. In early August, a squadron of American naval vessels, led by the ironclad USS Miantonomoh, dropped anchor off the Baltic port of Kronstadt, where a 21-gun salute and harbor festooned with U.S. flags awaited them.

The ensuing month of ceremonies, dinners, tours, fireworks, and other festivities celebrated the unlikely friendship, never formalized, between “the great Empire of the East, and the Great Republic of the West.” In his remarks to the czar, Fox praised “the unwavering fidelity of the imperial government…throughout the recent period of convulsion.” In return, Alexander promised to “contribute all his efforts to…strengthen the bonds.”

Today such mutual regard is in stark contrast to the enmity that has characterized Russian–American relations since the end of World War II. The connection between a young and growing democracy and an entrenched autocracy also struck some 19th-century observers as unusual: An English traveler during the 1850s attributed it to “some mysterious magnetism” drawing “these two mighty nations into closer contact.” But for many Americans, Russia seemed the most trustworthy of the European nations—an especially reliable buffer against the imperial schemes of Great Britain and France.

The two nations had enjoyed a diplomatic relationship since 1809, when James Madison appointed John Quincy Adams as the first minister to Russia. And in 1832, Russia became the first nation to enjoy “most favored nation” trading status with the United States. Staunch American support during Russia’s 1853-56 Crimean War against Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire would only strengthen the so-called “mysterious magnetism.”

Although the Franklin Pierce administration (1853-57) successfully blunted efforts by Baron Eduard de Stoeckl, the Russian chargé d’affaires in Washington, D.C., to craft a formal alliance, the United States supplied Russia with coal, cotton, munitions, and other war supplies. U.S. doctors and American volunteers served with the Russian army throughout the conflict.

In a dispatch to Russian Foreign Minister Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Stoeckl revealed no misconceptions about American motivations. “The Americans will go after anything that has enough money in it,” he wrote. “They have the ships, they have the men, and they have the daring spirit. “The blockading fleet will think twice before firing on the Stars and Stripes.”

Stoeckl’s surmise that Britain and France would adopt a hands-off approach to American shipping proved correct, and U.S. aid flowed freely to the czar’s army. The Russians’ defeat in 1856 did nothing to diminish their gratitude for the support they had received from the United States.

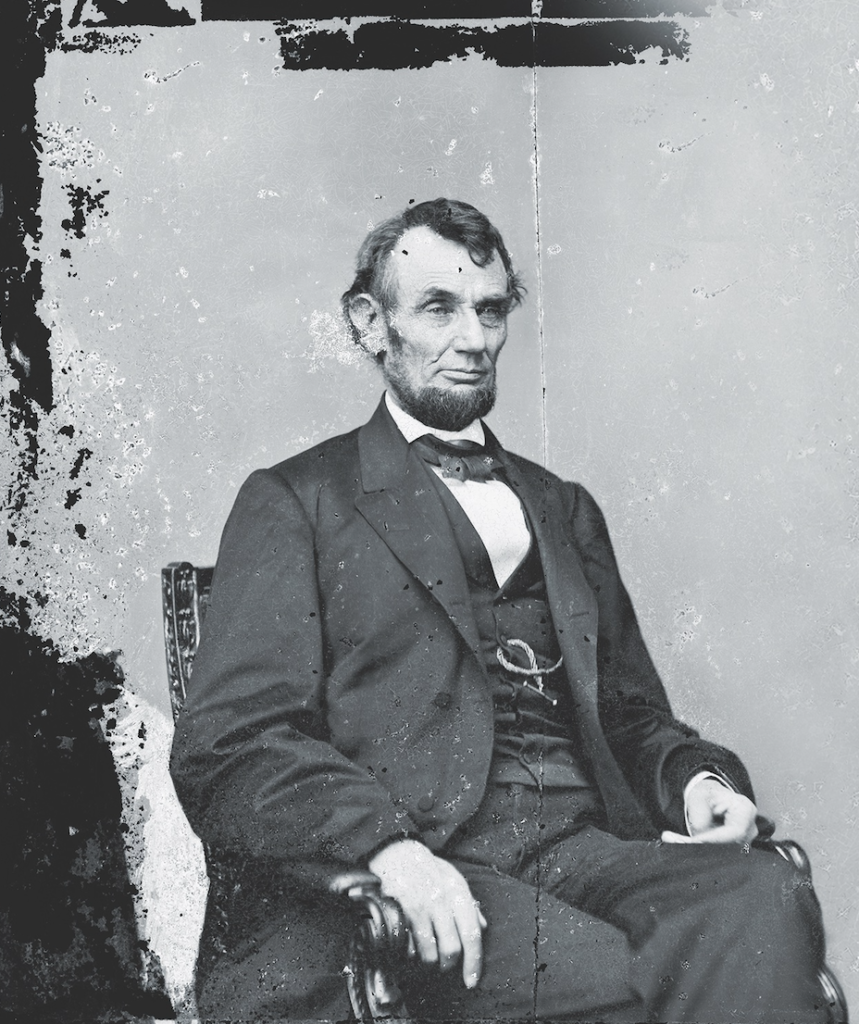

The election results of 1860 initially appeared to jeopardize the Russian–American entente cordiale. The new administration’s views of Russia, while still unformed, were generally critical: President Abraham Lincoln described it as a nation “where they make no pretense of loving liberty.” William H. Seward had lambasted Russia’s “despotism” in a number of speeches on the Senate floor before he took office as secretary of state. Stoeckl, who had been promoted to minister, called the new president weak, provincial, indecisive, and limited by his “gross inexperience in the management of the more important affairs of state as well as of military affairs.” Seward was, in Stoeckl’s words, “completely ignorant of international affairs,” yet possessed of a vanity “so great that he will not listen to anyone’s advice.”

Although the Russian minister’s analysis of the strengths of Lincoln and Seward was flawed, Stoeckl was a perceptive and experienced observer. In Washington since 1850 and married to an American, Elisa Howard, he had closely followed the growing rupture between North and South. Both sides, he believed, bore responsibility—“the North for having provoked it, and the South for wanting to precipitate events with a speed which makes rapprochement impossible.” While “the North can exist without the South,” he argued, “it will lose the principal source of its wealth and prosperity.” For the South, the only protection for slavery were the “the guarantees granted it by the Constitution.”

The outbreak of hostilities in April 1861 dramatically altered the foreign policy dynamic between Russia and the United States. While Russia certainly had no love for American democracy, and the United States was contemptuous of Russian absolutism, antipathy toward the leading European powers soon bound them together. The collective memory of America’s assistance during the Crimean War, the czar’s emancipation of 22 million Russian serfs on March 3, 1861, and the negligible impact of the American war on Russia’s agrarian economy all helped to strengthen the ties between these admittedly strange bedfellows.

Stoeckl and his superiors in Russia’s capital, St. Petersburg, embraced the belief that “the preservation of the Union is for our own best interests.” To further their aims, the Russians would refuse to “take sides with the secessionists prematurely…and not antagonize any State regarding matters which do not involve our interests.”

Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, met with praise from most of Europe. Ironically, the Russian response as embodied in Baron de Stoeckl’s reaction was among the most negative. A frequent critic of Lincoln, the Russian minister argued that the proclamation should have been “universal in its immediate application.” Instead, the document was a “military weapon” that was “not at all a proclamation of human liberty” and might well provoke a bloody servile insurrection throughout the South. Furthermore, it was “but a futile menace [because] it set up a further barrier to the reconciliation of the North and South—always the hope of Russia.”

The response from St. Petersburg was muted. Czar Alexander II’s conver-sation with an American banker years after the war suggests that the Russian ruler shared his minister’s misgivings. “I did more for the Russian serf in giving him land as well as personal liberty, than America did for the Negro slave set free by the Proclamation of President Lincoln….I believe the time must come when many will question the manner of American emancipation of the Negro slaves in 1863.” –R.B.

Russian and American interests quickly coalesced around the prevention of French and British interference in the Civil War. The British decision to recognize the belligerency of the Confederacy by declaring neutrality in May 1861 opened the possibility of recognition of the Confederate States of America as an independent nation. “England will take advantage of the first opportunity to recognize seceded states,” Stoeckl warned, “and France will follow her.”

Maintaining good relations with Russia was critical if the United States was to counter the growing hostility of both France and Britain. To represent American interests in St. Petersburg, Lincoln and Seward turned to Cassius Marcellus Clay, a pugnacious Kentucky abolitionist. Clay, who had worked hard for Lincoln’s election, coveted a Cabinet appointment as secretary of war. Failing that, he hoped for a post as minister to England or France. Too radical for inclusion in the Cabinet, Clay was forced to settle for the Russia post when Lincoln tapped others for the London and Paris assignments.

Seward’s instructions to Clay were straightforward. He was “to confirm and strengthen these traditional relations of amity and friendship” between Russia and the United States. Further, he was to convey to Czar Alexander Lincoln’s wishes that Russia and America refrain from any intervention in one another’s political affairs. The United States, in the president’s words, has “too much self-respect to ask more and too high a sense of its rights to expect less.”

Clay’s service got off to a rocky start. Before setting sail for Russia, he voiced a persistent lament that his annual salary of $12,500 ($328,000 today) was insufficient for his needs. “The Court of St. Petersburg is an expensive one,” he complained to Lincoln, and it ought to be “put upon an equality with the English and French [of] $17,500.” While crossing the Atlantic, Clay expressed further misgivings about his new post, asking to be made a general instead: “I think my talent is military….Make me a general in the regular service…and I’ll return home at once.”

In the fall of 1861, less than six months after arriving in St. Petersburg, Clay sent his family home. The following January, Lincoln decided to solve two problems at once. By appointing Clay a major general, he would presumably please his restive envoy while freeing up the post of minister to Russia for Simon Cameron. The Pennsylvania politico’s scandal-filled stewardship of the War Department had made him a political liability. After a rancorous debate, the Senate confirmed Cameron’s appointment, leading Frank Leslie’s Weekly Newspaper to quip that the nomination made Lincoln look “as if he were addicted to practical joking.”

Like his predecessor, Cameron proved reluctant to go to Russia, delaying his departure until May 1862 after an abortive attempt to return to the Senate. Cameron, too, stopped off in England, where Henry Adams weighed in with the hope that the “whited sepulcher General Cameron” would “vanish into the steppes of Russia and wander there for eternity.” And like Clay, Cameron almost immediately began plotting his return to the United States. When Seward denied his request for a furlough to participate in the 1862 fall elections, Cameron decided to accompany his wife back to the U.S. and then resign as minister to Russia.

In the meantime, Clay had decided that the military life was not for him and implored Lincoln “to return me to this court on Mr. Cameron’s leaving” since “you now have already too many generals in the field.” Recognizing that Clay was not fit for command, a “much annoyed” president decided to honor his request to return to Russia as minister. Clay’s appointment was widely criticized, and Seward had to step in at the last minute to save the nomination in the Senate. Bayard Taylor, who had served Cameron as secretary of the legation and hoped for the ministerial appointment himself, claimed Clay “had made the legation a laughingstock.” His “incredible vanity and astonishing blunders “are “still the talk of St. Petersburg.”

Despite his critics, Clay proved to be popular and socially adept during his second tour of duty in St. Petersburg. His parties rivaled any held in the Russian capital. “If they liked flowers, I accommodated them,” he boasted, “if paintings, I had invested in some of the rarest; if wines, I had every sample of the world’s choice; if menu was the object, nothing there was wanting.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Throughout much of 1862, while Simon Cameron and Cassius Clay were engaged in an almost comic diplomatic pas de deux, France and Great Britain were exploring ways they might intervene to broker a peace that would lead to Confederate independence. Both nations saw in the potential dissolution of the United States the beneficial removal of an emerging power from the world stage. In the early spring, Henri Mercier, the French minister to the United States, began sounding out his British and Russian counterparts about playing a role as mediators. The effort quietly collapsed after Stoeckl reported on a conversation with Seward, who declared the war “a domestic quarrel which must be settled among ourselves” and warned potential interlopers that “mediation from whatever source will not be popular with our nation.”

Undaunted, the French tried again in July, asking the Russians to lead a mediation attempt. Prince Gorchakov flatly refused. “Russia and America,” he noted, “have a special regard for each other which is never adversely affected because they have no points of contact.” In the fall, the British tried their hand, proposing an armistice requiring the Union to lift its blockade and negotiate a peace based on Confederate separation. If the North refused, British leaders hinted that they might then recognize the South. At the same time, the French renewed their effort to broker a peace.

Once again Russian participation was critical to the washout of both initiatives. For their part, the Russians viewed the United States as a valuable counterweight to the global ambitions of the British and so favored a reunion of North and South. In St. Petersburg, Prince Gorchakov warned Bayard Taylor that England “longs and prays for your overthrow…[and] France is not your friend.” Russia alone, he continued, “has stood by you from the first, and will continue to stand by you. We believe that intervention could do no good at present…[and] will refuse any invitation of the kind.” But Gorchakov also expressed his nation’s anxiety-laden wish that the Lincoln administration find some means to “prevent the division which now seems inevitable.”

From Washington, Stoeckl offered support for his government’s hands-off policy. Recognition of the Confederacy by France or England “will not end the war and…will not procure cotton.” The latter could be accomplished “only by forcing open the Southern ports,” a move that would lead “to a clear rupture with the North.”

By late November 1862, the last concerted effort by European nations to intervene in the Civil War fell apart when both Britain and Russia rejected the French proposal. The entire effort, Lincoln noted, had been the result of a “mistaken desire to counsel in a case where all foreign counsel excites distrust.” One Washington newspaper spoke for many knowledgeable Americans when it editorialized, “Russia has obtained the deep gratitude of this country.”

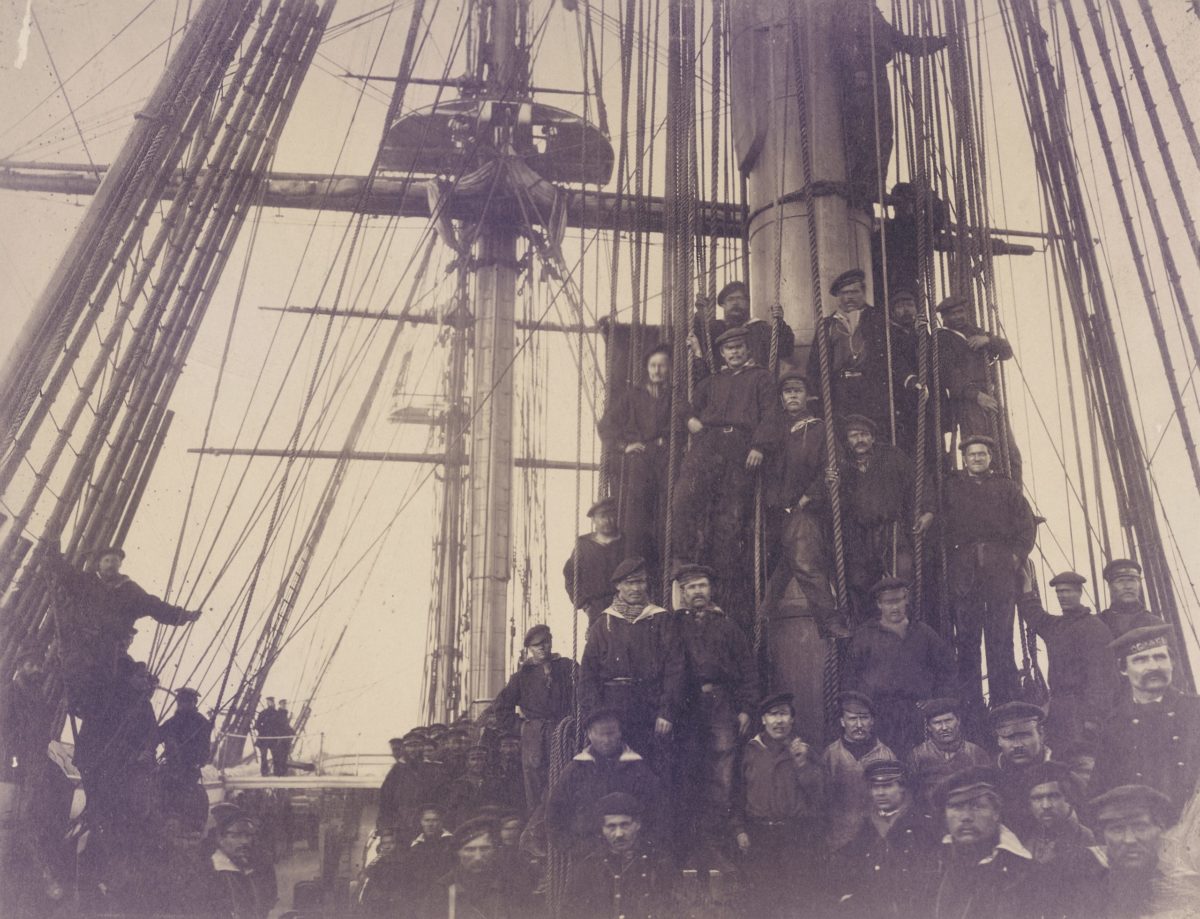

Within a year, Northern supporters had yet another reason to be grateful to Russia. In early September, the arrival of Oslyabya in New York Harbor brought news that five other Russian warships under the command of Rear Admiral Lisovskii were en route. The frigate’s unannounced appearance generated considerable excitement, and on September 16 a delegation that included First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, Maj. Gen. John A. Dix, Russian Consul-General Baron d’Ostensacken, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ wife, Mary, paid a visit, during which they drank a toast to Czar Alexander II.

On September 24, 1863, four days after the Federal army’s crushing defeat at Chickamauga, two Russian frigates—Alexander Nevskii, and Peresviet—arrived, followed by three more vessels by mid-October. To many, their presence seemed to reaffirm Russian support for the Union cause. For Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, the squadron’s presence was “a politic movement for both Russians and Americans, and somewhat annoying to France and England.” He quickly made the facilities of the Brooklyn Navy Yard available for any necessary repairs.

The entrance of six ships from Russia’s Far East fleet into San Francisco Harbor on October 12 seemed a further token of Russian friendship. In fact, the foreign vessels remained in American waters for the next seven months, providing a welcome distraction.

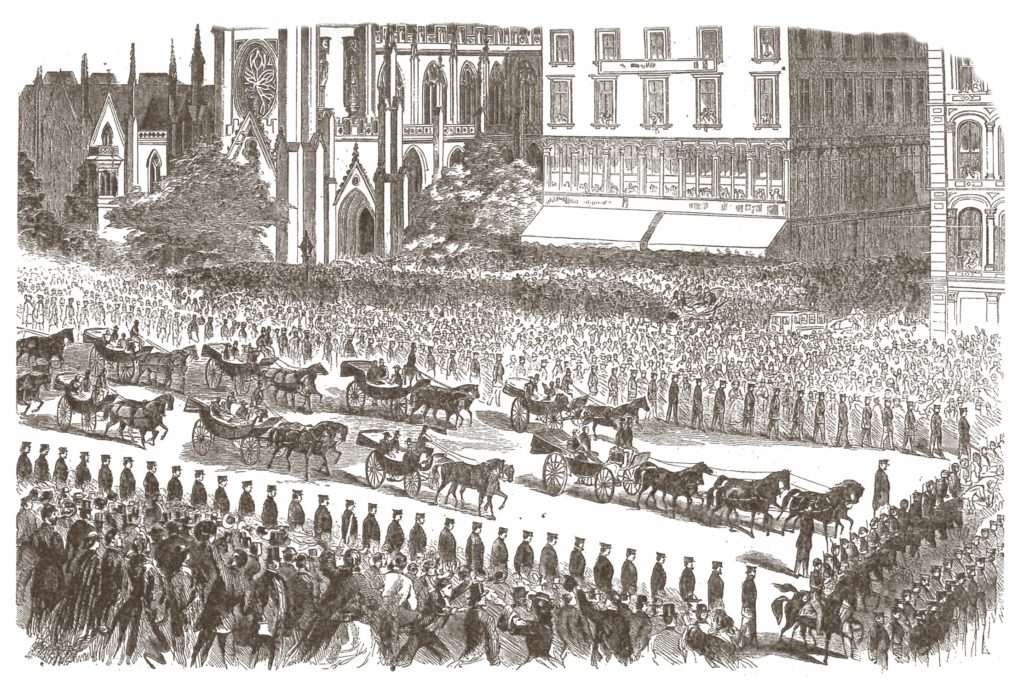

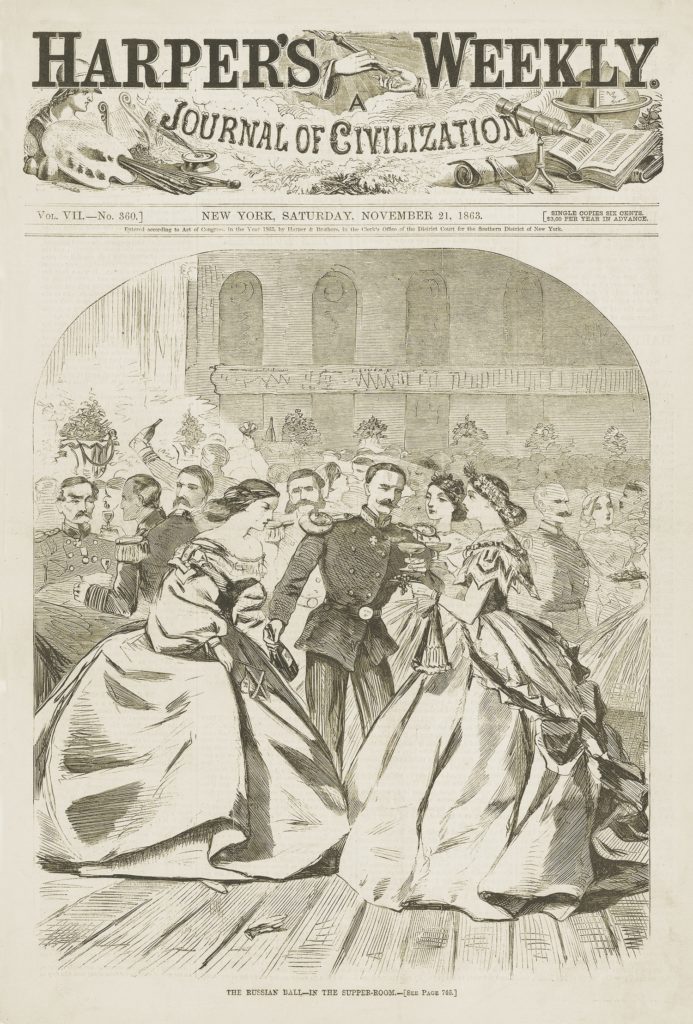

New York welcomed the Russian fleet with a series of celebratory events—a parade down Broadway, a reception with Mayor George Opdyke, and two banquets. The grandest of these fetes—the Soirée Russe honoring the Russian naval officers—took place at the Academy of Music the evening of November 5. Luminaries such as John Jacob Astor, Hamilton Fish, and wealthy banker Moses Taylor hosted the event, which drew more than 2,000 of the city’s social elite to eat, drink, and dance beneath portraits of Peter the Great, George Washington, Czar Alexander II, Abraham Lincoln, and Union military notables such as Ulysses S. Grant and David Farragut.

Guests began arriving at 9 p.m. and two hours later sat down to a supper catered by Delmonico’s, New York’s premier restaurant. Harper’s Weekly catalogued the evening’s lavish bill of fare, including 12,000 oysters, 12 “monster” salmon of 30 pounds each, 1,200 game birds, 250 turkeys, 400 chickens, a half ton of tenderloin, 100 pastry “pyramids,” 1,000 loaves of bread, and 3,500 bottles of wine.” Following the meal, dancing and socializing extended into the wee hours of the next morning.

The following month, when the fleet sailed south to the Chesapeake Bay, then up the Potomac to Alexandria, Va., Lincoln hosted the Russian officers at a White House reception. In attendance were Cabinet members, the diplomatic corps, Supreme Court justices, and members of the Lincoln administration such as presidential secretary John Hay, who described the Russian guests as “fiendishly ugly” but marveled at their “vast absorbent powers.”

The political significance of the balls, ceremonies, parades, and receptions that greeted the Russians was not lost on most observers. There were, however, critics. “Such extravagant festivities were out of place when the Boys in Blue were dying in the trenches and when the government was having hard work to raise money for munitions,” protested one New York newspaper. “The million spent on the ‘Ovation, Collation and Ball’ should instead have been given to the Sanitary Commission.”

The reasons for the fleet’s visit remain open to interpretation. While there is little doubt that the Russian government saw it as an opportunity to display its support for the Lincoln administration, considerable self-interest was also at work. The Russians were anxious to avoid their misfortune of 10 years earlier when the British and French navies had been able to trap the Russian fleet in the Baltic during the Crimean War. Should war now break out over the Russians’ brutal suppression of a revolt in Poland, the czar wanted his fleet to be available and in position to raid enemy shipping. The voyage to North America also provided opportunities to demonstrate the Russian navy’s capabilities and to observe the Union ironclads that promised to revolutionize maritime warfare.

Once the Russian squadron reached American waters, its orders were to “drop anchor in New York…[and] await the outcome of the negotiations on the Polish question.” Should the U.S. government object to their presence in a single harbor, the Russian admiral was “to divide the squadron into two or three parts and to scatter it among ports of the North American coast.” From there, the Russian fleet could attack enemy shipping should war break out over the Polish question.

Foreign Minister Gorchakov had been consistent in impressing upon Stoeckl and the fleet commanders that they were not to interfere in the fighting. “We desire above all things the maintenance of the American Union,” he wrote in 1862. “We cannot take any part more than we have done. We have no hostility to the southern people.”

During the winter of 1863-64, the threat of war in Europe evaporated, and on April 26, 1864, orders arrived directing the Atlantic and Pacific squadrons to return to Russia. In retrospect, one historian has written that a stance appearing to favor the Union was smart policy for the Russians: if the North won, it would be grateful, while if the South won, it would be so elated that it would soon forget its grievances. The staunchly Democratic New York Herald wondered what had been gained by the fleet’s presence, noting that “Russia sends her navy here to keep it safe [but]…we doubt if she would send it…to aid us in fighting England.” Her navy, in fact, was “not worth the sending.” The author rather accurately, if somewhat insultingly, observed that “one of our Ironsides could blow it out of the water…in a couple of hours.”

Although Lincoln and Seward both recognized that the Russian fleet’s presence in American waters signified neither a promise of military support nor opposition to slavery, they skillfully deployed it to discourage foreign intervention on behalf of the Confederacy. They were “astute enough to see that this visit of the Russian squadron might seem to be what it was not,” observed one contemporary. “Appearances, we all know, are sometime deceptive.” The visit of the squadron was “a splendid ‘bluff’ at a very critical period in our history.”

By early 1865, a Union victory and the resulting national reunification—always the Russians’ goal—seemed increasingly likely. Baron de Stoeckl and his colleagues in St. Petersburg began to ruminate on the war and the challenges of the postwar era. Always a harsh critic of Lincoln, whom he felt lacked leadership qualities and moral courage, Stoeckl took pains to explain the Union victory. “Providence has taken [Americans] under his special protection,” he suggested. “The insurrection was put down not by the skill of the men in authority, but by an irresistible strength of the nation at large.”

Stoeckl praised Ulysses Grant’s “commendable” moderation at Appomattox and hoped it would set an example for the politicians. His analyses of the aftereffects of the bitter enmity between North and South over slavery were prescient: He saw trouble ahead. “How can it be expected that States which have waged a long and fierce war can rejoin the Union and live in peace and harmony with the loyal States?” he asked. It is rather improbable that the people of the South could be persuaded “to form a new attachment to the Union.” Stoeckl predicted an equally bleak future for relations between Whites and the new freedmen and women. “The Negro will be tolerated only so long as he is useful to the Americans who, like all Anglo-Saxons, are always ready to speak piously about the rights of humanity, but are slow to put them into practice.”

The unlikely friendship between Russia and the United States during the Civil War paid dividends for both countries. While it may not have been the decisive factor in discouraging European intervention—the Union victory at Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation cannot be discounted as determinative factors—the Russian refusal to join the mediation efforts of Great Britain and France effectively squelched attempts at foreign intervention. Russian support also strengthened Union resolve at key moments. In return, the Lincoln administration’s refusal to condemn the czar’s suppression of the Polish revolt likely discouraged European intervention in what Lincoln and Seward considered a problem internal to Russia. Finally, the United States’ enmity for Britain in particular provided a strategic counterbalance that aided Russia’s emergence on the world stage. It proved to be an alliance of strange bedfellows that, however informal, served both nations well.

This article first appeared in America’s Civil War magazine

Facebook @AmericasCivilWar | Twitter @ACWMag