In 1814 James Madison rode into the Battle of Bladensburg and became the first sitting president to be on a battlefield under fire.

It was close to noon on August 24, 1814, when a 4,500-man British army finally marched within sight of Bladensburg, Maryland, nine miles northeast of Washington, D.C. As the army’s 1st Brigade approached the seemingly vacant river town, it mounted nearby Lowndes Hill, giving Major General Robert Ross a commanding view of the American forces deployed just across the river. There were lots of them, and they clearly aimed to defend a 90-foot wooden bridge over the Eastern Branch of the Potomac River.

Suddenly, with the British troops in proximity, President James Madison galloped onto the scene, his entourage in tow. Madison proceeded to ride across a ridge overlooking the entire battlefield, past a line of raw militiamen posted in an orchard, and then well past the front line where an earthwork shielded riflemen and artillery pieces that had been moved down from Baltimore, which Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. had deemed Ross’s likeliest target.

That morning, on the other side of the river, William Simmons, a civilian, had been scouting the enemy’s progress. He’d been anxiously scanning the river road when, through the heat-warped summer air, the dense British columns finally appeared. As the enemy troops marched into Bladensburg, Simmons realized that he had better cross over to the American side of the river. As he reached the bridge he was startled to encounter President Madison’s party, evidently intent on riding across it, directly into the ranks of the onrushing enemy.

“Mr. Madison!” Simmons shouted, “the enemy are now in Bladensburg!”

Elected to the presidency in 1808 and reelected in 1812, Madison was known as the father of the U.S. Constitution and for drafting its first 10 amendments—the Bill of Rights. But now, at age 63, he was a small and sickly man. He had no military experience.

The Battle of Bladensburg was a monumental military disaster for the fledgling nation. Yet that day, as an outnumbered British army of regulars and Royal Marines easily routed a combined U.S. force of Regular Army and state militia units, a sitting American president bravely ventured onto a battlefield under fire.

The United States declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812. The reasons were many, including the hostile acts Madison listed in his famous War Message to Congress: “The continued practice” of British cruisers “violating the American flag on the great highway of nations” by “carrying off persons sailing under it” (i.e., the impressment of American merchant sailors into the Royal Navy); and “the warfare just renewed by the savages on one of [America’s] extensive frontiers”—warfare that British officers in Canada seemed to have encouraged.

With its army and navy tied down fighting the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain had little choice in 1812 and 1813 but to adopt a defensive military strategy in Canada as the United States launched repeated invasion attempts. (Most ended in humiliating losses for the Americans.) But this limited warfare ended in 1814 following Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube and his unconditional abdication as emperor of France. With its troops and ships now freed up, Britain could now go on the offensive.

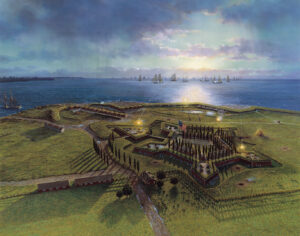

It did so with alacrity. On August 15, 1814, a large British fleet—20 warships along with numerous transports and supply vessels—sailed into the Chesapeake Bay. Four days later a British army went ashore at Benedict, Maryland, some 25 miles up the Patuxent River, and—startlingly—just 25 miles, as the crow flies, from Washington, D.C.

On August 18, Secretary of State James Monroe—a combat veteran of the Revolution who longed to be back in the military—led a troop of cavalry out of Washington. Scouting the enemy army, he reported to Madison an accurate assessment of its size, telling him that the British seemed intent on taking the American capital. He also tried to facilitate communication between Tobias E. Stansbury and Henry Winder, the two brigadier generals charged with defending Washington. Stansbury, with a 2,200-man brigade, aimed to block the enemy’s advance. In the capital itself, Winder was hastily assembling another force that eventually grew to about 3,200 men. Unfortunately, only 625 of them were U.S. Regulars.

As Ross’s forces marched north out of Benedict, Monroe continued watching their movements. Ross stuck close to the west bank of the Patuxent. On the Patuxent itself, a British naval flotilla under Rear Admiral George Cockburn kept abreast of Ross’s leading files, covering the army’s right flank while providing supplies. When the flotilla could go no farther, Cockburn came ashore, bringing with him four companies of Royal Marines and a rocket detachment.

Wednesday, August 24, dawned warm and clear. With rumors rife in the federal capital, the roads to Virginia were already clogged. In government offices, clerks were hastily packing the administration’s documents.

Early that morning President Madison had received a message from the sleep-deprived Winder saying that he required, as Madison put it, “the speediest counsel.” At a subsequent meeting at Winder’s camp—attended by most of the Cabinet secretaries, including Monroe—it was reported that the British were marching on Washington via Bladensburg. Monroe was immediately dispatched to Bladensburg to help position Stansbury’s Maryland militia. Then it was decided that Winder’s force would march out to reinforce Stansbury. Once there, Winder would be in command.

Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. was strangely silent for most of the meeting. Finally, he spoke up, Madison later noted in a memorandum, saying that the American militiamen, as they were going up against British regulars, “would be beaten.” Madison, upset at Armstrong’s remark, instructed him to join Winder at Bladensburg. And Madison promised to be on the battlefield himself, should there be any “difficulty on the score of authority.” This meant that Winder, dog tired, would be facing “Wellington’s Invincibles”—seasoned soldiers so named for their string of successes against Napoleon—while dealing with a meddlesome president and a naysaying secretary of war. It was a recipe for disaster. As Madison prepared to leave, Treasury Secretary George W. Campbell handed him a pair of dueling pistols.

On the way to Bladensburg, Madison encountered Commodore Joshua Barney, a veteran naval officer whose flotilla of gunboats, galleys, and barges had been bottled up in the Patuxent River by Cockburn’s larger force. Hoping to see action on land, Barney had mounted his five biggest guns on wheeled carriages, scuttled his ineffectual fleet, and then marched his cannons and flotillamen—500 sailors and marines—to Washington. This naval force had been sent to guard a bridge of little importance. Then, evidently, Barney’s men had been forgotten. Barney angrily told the president that they could be put to better use at Bladensburg. Impressed by Barney’s martial spirit, Madison agreed.

By 11:30 a.m. all the American reinforcements were finally on the move to join Stansbury’s militia force at Bladensburg. Unaware that reinforcements were on the way, Stansbury struggled to position his 2,200 militiamen. Some 350 yards west of the Bladensburg bridge, Stansbury placed six-light cannons and a battalion of riflemen behind an earthwork. He positioned three regiments of supporting troops 50 yards to the rear, in an apple orchard. Two were regiments of drafted militia; the other was an outfit of inexperienced volunteers. These units could quickly reinforce the troops behind the earthwork, if needed, or move to either flank. Stansbury was pleased.

Then Monroe rode onto the battlefield and, without notifying Stansbury, rearranged the supporting troops. He ordered the three militia units farther to the rear—too far, in fact, to be of assistance. When a militia regiment from Annapolis arrived, Monroe posted it on an isolated hill fully a mile to the rear. Another mistake.

As the British field army came into view across the river, Winder’s reinforcements started arriving. The first unit, a cavalry squadron, trotted down the road to Bladensburg looking for guidance. Monroe directed it to a ravine behind and far to the left of Stansbury’s line. Riding into the gully, the horsemen quickly realized they couldn’t see out of it.

Behind the cavalrymen came President Madison’s party. Unaware of the danger, Madison rode all the way through the American positions until William Simmons shouted at him from the bridge.

The president, apparently, was stupefied. “The enemy in Bladensburg?” Simmons later recalled him shouting back. Madison and his entourage immediately reined in their horses, wheeled about, and galloped off. But for the vigilance of a civilian scout, the president of the United States might well have fallen into the hands of the enemy.

After this perilously close call, Madison and his party quickly retreated behind the first American line, where they encountered Monroe, Winder, and Armstrong. Then the British opened the ball. At first, taken aback by the number of enemy troops in plain view on the hills across the river and the artillery blasts from the American earthwork, Ross decided to attack with his 1,100-man 1st Brigade when he realized that most of the Americans had to be militia, as they weren’t wearing uniforms.

Ross had wanted to soften up the Americans, but he hadn’t brought along any field artillery. Royal Marines were soon seen setting up some strange tripods along the riverbank, and then “whoosh”—flaming rockets were in the air above the startled Americans. The rockets, invented in 1804 by Sir William Congreve, featured a sheet-iron cylinder—holding the warhead and the propellant—at the business end of a long stick that was supposed to stabilize their flight. They flew erratically but were nonetheless unnerving to those on the receiving end.

Winder, seeing Stansbury’s militiamen starting to waver, dashed behind them, yelling, “Don’t be afraid, they’re perfectly harmless.” Some of the men may have believed him. When Winder reached Madison’s party, he stopped long enough to suggest that the president should move farther back. As they trotted to the rear, the artillery that had been brought down from Baltimore continued a lively exchange with the enemy sharpshooters and rocketmen lining the river.

Soon thereafter, the entire British 1st Brigade—bayonets flashing, Ross well in front—charged across the bridge and deployed into battle lines on the American side. There was something utterly unnerving about the British Regulars—their discipline, their confidence, their weapons. The American units at the earthwork started to dissolve. Scrambling to hold his first line, Winder ordered the supporting troops forward. A new salvo of flaming rockets, however, sent them scampering to the rear. Soon even Stansbury’s best unit was running away pell-mell. Although they had suffered few casualties—and few had even fired a shot—Stansbury’s militia brigade was already routed from the field.

Madison, Monroe, Armstrong, and Attorney General Richard Rush were well to the rear when the army started to collapse. Monroe made a futile attempt to rally the frightened militiamen. Armstrong galloped away by himself. Madison and Rush headed back to Washington, undoubtedly finding it hard to imagine that such a disaster could have befallen the Americans so suddenly.

As they rode off, they passed Barney’s force, just now arriving on the field. An American second line was quickly forming on a convenient ridgeline. District of Columbia militia units and U.S. Regulars held the left. The Annapolis regiment still sat on the far right. Into the center rushed Barney’s marines and flotillamen, the commodore’s five big guns planted directly astride the main road to Washington.

Stansbury’s rapid retreat had left a vacuum on the battlefield, and it didn’t take long for the British to fill it. As the lingering haze from the battle dissipated, the enemy’s red coatees came into view. Ross’s 1st Brigade was now bolstered by the 2nd. When an advance militia regiment broke and fled, Ross wasted no time in deciding to continue the attack. Three times the 85th Regiment of Foot surged up the ridge against Barney’s force; three times they were driven back by grape and canister blasts from the big guns. Thrilled at the sight of redcoats turning tail, Barney decided to strike back. He ordered a charge, and soon his men, seeing most of the British hiding behind a fence, swarmed over the rails, cutlasses raised.

The 85th Foot gave way after a few minutes of hand-to-hand combat, with some of the men scrambling all the way back to the river. Barney’s men returned to their ridgeline position. But it was too little too late. When the British attacked again, both American flanks were driven in. Winder, thinking he could save some of the men, rode up through the smoke and ordered the entire second line—what remained of it—to retreat. The direct route to Washington was now wide open.

The British lost some 250 killed and wounded in the fighting; American losses totaled about 150. The British captured 10 American guns but were able to take only about 120 soldiers prisoner. The rest had simply run too fast to get caught.

The Americans’ defeat at Bladensburg was embarrassing enough, especially as it was now only 4 p.m. But August 24 was about to serve up another humiliating blow to the national honor.

At the White House earlier that afternoon, First Lady Dolley Madison had written in her journal: “We have had a battle…near Bladensburg, and I am still here within sound of the cannon!” As she sped west to safety, President Madison rode into Washington amid a swirling mob. For him, safety lay across the Potomac River in Virginia; for Winder and Monroe and the regimental remnants, the next stop was Georgetown. Stansbury’s militiamen were already well on their way back to Baltimore.

Meanwhile, after a brief respite, Ross and Cockburn led the fresh British 3rd Brigade into Washington. They dispatched raiding parties to burn the city’s public buildings, including the Capitol, the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Treasury Department, and the War Office. Cockburn and his men looted the White House before they set it on fire.

Wellington’s Invincibles tramped out of Washington the next day, leaving behind a city that was little more than a smoldering ruin. The British retraced their steps to Benedict, where they reembarked on August 30. In just 10 days the British had penetrated enemy territory, won a battle against a larger army, and captured and burned the enemy’s capital—all at the loss of fewer than 300 men.

Madison, incensed over the national humiliation, demanded Armstrong’s resignation and got it. He replaced Armstrong with Monroe.

A stain on the nation’s history, the Battle of Bladensburg nonetheless taught Madison two valuable lessons. First, it dispelled the idea that militiamen could be counted on to hold their own against an enemy’s well-trained regulars. And it proved that an active battlefield was no place for the nation’s chief executive.

Fortunately for President James Madison and the young American nation, a victory at Baltimore, where Ross would be killed, was just a bit over two weeks away. And on December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent would formally end the War of 1812.

Rick Britton, a historian and cartographer, lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.