In celebrating Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s triumph at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, newspapers across the North enthusiastically conjectured that this latest in a series of spectacular Union successes would finally end military operations in the Shenandoah Valley. The battle had begun disastrously for Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah, but the Federals famously rallied to victory following Little Phil’s heroic, mid-morning ride to the battlefield from Winchester. Six days after the battle, The New York Evening Post noted that the Army of the Shenandoah seemed gripped with “enthusiasm…after the defeat of the enemy” and it “is generally believed…there will be no more serious fighting in the Valley.” On October 23, a correspondent for Iowa’s Muscatine Evening Journal concluded the same, proclaiming, “Sheridan’s victory at Cedar Creek makes the third he has gained during the present campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. This last defeat will, it is more than probable, end the campaign on the part of the enemy in that region.”

Celebration by the press that Sheridan and the Army of the Shenandoah had snatched “victory from the jaws of defeat” at Cedar Creek was justifiable. Furthermore, particularly in the minds of President Abraham Lincoln’s supporters, Sheridan’s recent wave of success had significantly buoyed Lincoln’s chances for reelection in November. Yet in Sheridan’s army itself, the soldiers’ mood generally remained much more restrained, reflective, and somber. Veterans especially found it difficult to reconcile the joy of victory with the grief they felt over the loss of killed comrades. Two days after the battle, Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, commanding a cavalry division in Sheridan’s army, and Brig. Gen. Frank Wheaton, a division commander in the army’s 6th Corps, addressed troops in the 15th New Jersey Infantry. Alanson Haines, the 15th New Jersey’s chaplain, recalled that men “rejoiced in victory” and “tried to cheer, but their hurrah was faint and weak.”

Juxtaposed against the backdrop of fresh graves, the 15th’s veterans weren’t feeling much elation. As Custer and Wheaton talked, in fact, Haines found himself transfixed on the grave of Sergeant John Mouder, the color-bearer of the unit’s state banner, killed during the morning’s fighting. “Just over the hill and almost in sight was the little mound which marked the spot where young Mouder slept,” Haines wrote. “His ear was deaf to the words of commendation…our best cheer failed to arouse his attention.” Gnawing at him was the perception that “the country was jubilant over Sheridan’s victory,” but “did not know and appreciate the sufferings of those who had won it.”

In the battle’s aftermath, other Union veterans reflected with similar somberness. Corporal Charles Shergur of the 9th New York Heavy Artillery recorded his thoughts after visiting his unit’s former campsite and finding a discarded drum head. “I come to the very ground where my tent stood in the morning, but now I miss my tent-mate and comrade,” he would write. “I feel lonesome and utterly exhausted[,] I lie down on the ground. Victory was on our banner, but our comrades living and dead mingle together on the ground.”

Beyond such melancholy reflections, the army’s veterans also confronted the stark reality that Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early likely wasn’t done yet. Despite bold statements from newspaper correspondents that Confederate forces in the Valley no longer posed a threat, the Federal soldiers did not feel so certain. As November approached, Corporal James Thatcher, also of the 9th New York Heavy Artillery, told his brother: “[W]e expect another hard fight at Cedar Creek within a short time.”

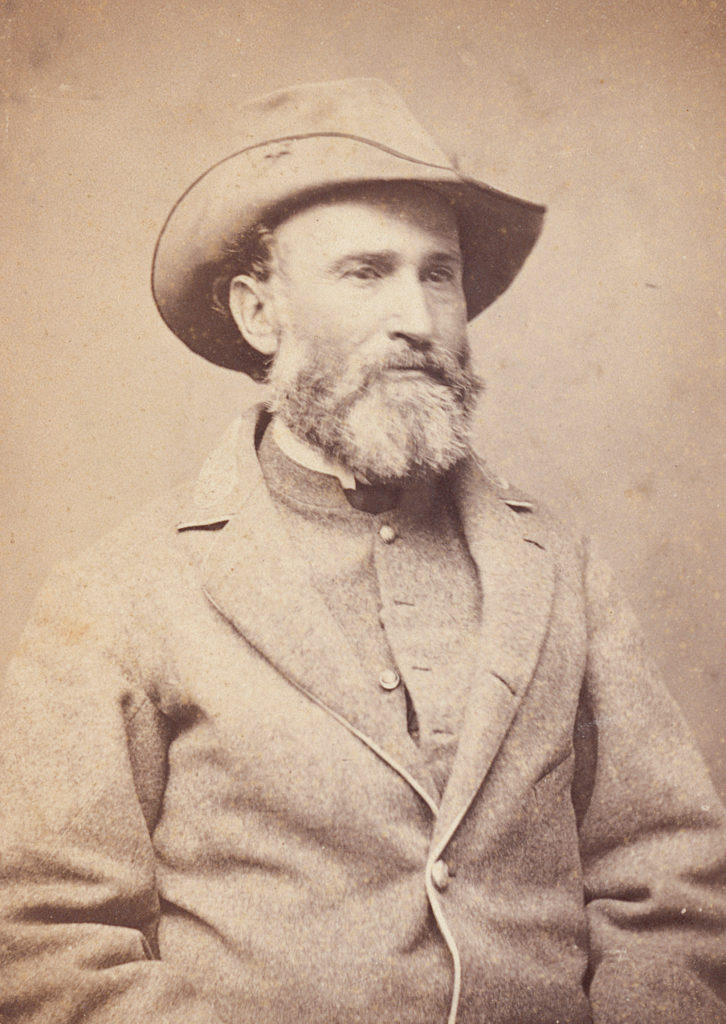

On October 27, Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, who commanded a division in Sheridan’s army, wrote to his wife that he believed another attack possible, especially if Early hoped “to interfere with the election.” Three days later, Captain Charles Washington Kennedy, 156th New York Infantry, did the same in a letter to his wife, Kate: “There is a general impression that we will have another fight before we go into winter quarters.”

In Cedar Creek’s immediate wake, continued harassment from Confederate partisans, irregulars, and bushwhackers only added to the uncertainty. Sheridan had been particularly annoyed by “guerrilla bands” throughout the campaign. Though conceding he wouldn’t entirely eliminate all of the threats they posed, the general was confident these guerrillas could be curtailed by depriving them of potential manpower. On October 22, Sheridan ordered the arrest of every Confederate male civilian capable of bearing arms, a directive the region’s civilians understandably found unconscionable. Among the staunchest of Confederate supporters in Winchester was Mary Greenhow Lee, who declared it “an outrage for our citizens to be shut up in a horrid Yankee Guard House.”

Some of those called upon to enforce the edict had misgivings, too. Believing it would only further alienate the Confederate civilians population, Mason Whiting Tyler, an officer in the 37th Massachusetts Infantry, wrote his parents the day after Sheridan’s order: “The order has just been issued by General Sheridan for the arrest of all male citizens in the Valley…who are capable of bearing arms. It will cause such a commotion…as has not been seen since the war commenced.”

After a few days of arrests, Tyler lamented to his brother that arresting “citizens of disloyal tendencies”—including “some old men sixty or seventy years of age and much broken down with the infirmities of old age”—was “too relentless” and made him “uneasy.” Nevertheless, Tyler accepted that as much as he detested the practice, he possessed “no right to express an opinion.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Sheridan soon had to heighten security even further after three unidentified Confederate soldiers recovering from wounds escaped from Winchester’s York Hospital. Mary Greenhow Lee, who regularly attended the wounded at the facility, had reportedly had a conversation with those three soldiers a day earlier and when informed of their plot had advised them against it. Lee unabashedly detested Sheridan and his army, but she also believed he would make life even more difficult for area inhabitants if they escaped, even pleading with one prisoner “not to go…knowing it would create a disturbance.”

As she feared, it did. Sheridan responded by intensifying the hospital’s guard and permitted no one to enter or leave without a pass. Further, Sheridan forbade local Confederate women from serving as nurses.

On the day of the escape, a contingent of Lt. Col. John Singleton Mosby’s vaunted Rangers captured seven wagons, 54 infantrymen, 30 mules, eight horses, and Union Brig. Gen. Alfred Duffié during a raid north of Winchester. A day later, 44 soldiers of the 26th Massachusetts, commanded by 2nd Lt. Joseph McQuestion, were captured while guarding a forage train near Newtown—more than likely by another party of Rangers commanded by Captain Adolphus “Dolly” Richards, one of Mosby’s most trusted subordinates.

The Massachusetts soldiers were sent to prison camps in Richmond. Although most survived and were exchanged in February and March of 1865, three died in captivity: Charles F. Robbins, a farmer from Shirley; Simeon Ward, a bootmaker from Hopkinton; and Peter Alexander, a farmer from Wilmington.

Army of the Shenandoah soldiers were worried not only by the possibility of capture while escorting wagon trains, but also when they were detailed to guard civilian property. Because Sheridan prohibited the “seizure of property by Officers or Enlisted men of this Army” unless they possessed his “written authority,” Little Phil permitted civilians, regardless of allegiance, to request guards. Among those assigned to such duty was Private John Flint of the 116th New York Infantry. A 24-year-old farm laborer from Erie County, N.Y., Flint was detailed to protect the property of the Walls family in Newtown—a locality that had gained notoriety throughout the war as a safe haven for Confederate partisans, irregulars, and bushwhackers. Fearing he might be “betrayed” to Mosby’s men, Flint came across somewhat standoffish to the family matron, Mollie, in the assignment’s early days. His apprehension was no doubt warranted, as the Walls had already entertained elements of Mosby’s command on various occasions.

Although she supported the Confederacy, Mollie Walls appreciated Flint’s presence in helping keep her family safe, particularly as supplies become more scarce with the approach of winter. Civilians could purchase any supplies they needed but were free to do so only with a permit from the Army of the Shenandoah’s provost marshal. The only way to procure one, Walls recalled, was “to take the oath of allegiance to the U.S.”—something she refused to do.

Requiring civilians to take an oath of allegiance had been an oft-used tactic to break civilians’ Confederate loyalties, yet many Valley locals had figured ways to circumvent the system, including playing on the sympathies of Union soldiers. On numerous occasions in November–December 1864, Flint would be the one to buy what the Walls “needed” from area sutlers and apparently did not expect reimbursement, even though Walls noted that the family “would always pay him back.”

Indictments of Early

In defeat, Early and his Army of the Valley retreated from Cedar Creek toward the crossroads town of New Market, site of a shocking Confederate victory back in May, before Sheridan had assumed command of what had been known as the Department of West Virginia and begun to reverse Federal fortunes in the so-called “Breadbasket of the Confederacy.” His army camped in the vicinity of New Market, Early was facing harsh criticism—reproach that only intensified after the general’s scathing indictment of his army appeared in The Richmond Enquirer on October 23.

Early had publicly lambasted his command for plundering abandoned Union camps during the battle’s early hours. That, Early contended, had significantly slowed momentum and had singlehandedly reversed the promise of a Confederate victory. The Enquirer article—headlined “An Address from Gen. Early to His Troops”—echoed the report Early had sent to General Robert E. Lee on October 21. “By your subsequent misconduct, all the benefits of that victory were lost… ,” Early berated his troops. “Had you remained steadfast to your duty and your colors, the victory would have been one of the brilliant and most decisive of the war… But many of you…yielding to a disgraceful propensity for plunder, deserted your colors to appropriate to yourselves the abandoned property of the enemy.”

Artillerist Thomas Henry Carter was among those in Early’s command to denounce their commander. On October 26, Carter wrote his wife from New Market that though Early “has many good qualities of a soldier,” he “is no Genl. On the battlefield he is without particular aim or plan & the fighting under his control is languid.” Echoed George Nichols of the 61st Georgia: “We could not help but blame General Early for all the disasters at Cedar Creek… he never had the confidence of his men after [that].”

Indictments of Early also poured in from civilians in the Valley. Sarah L. McComb, a resident of Augusta County, wrote to President Jefferson Davis calling for Early’s immediate removal from command. “[T]here will never be any thing but defeat & disaster until [he] is relieved…” McComb wrote. “[M]en & Senior officers have lost all confidence in their leader.”

Beginning November 8, Sheridan moved the Army of the Shenandoah from its camps along the banks of Cedar Creek north to the vicinity of Kernstown. With reconstruction work on the Winchester & Potomac Railroad nearing completion from Harpers Ferry to Stephenson’s Depot, it was a prudent move, as it improved Sheridan’s capacity to resupply his army.

By the second week of November, the Army of the Shenandoah indeed faced a severe supply crisis, particularly being able to provide enough hay for the army’s horses. The situation had become so dire that Corporal Robert Bradbury, Battery D, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, wrote his sister Harriet that “our horses had become so ravenous that they eat up most of the halter straps…spoiled about a dozen caisson wheels by eating clean through the spokes” and “whenever one horse could get at the tail of another he chawed all the hair off as clean as if it were a razor.” The sight of horses without tails, Bradbury noted, was “a most ludicrous spectacle.”

In addition to being able to better supply the army, Sheridan decided re-situating his army in the vicinity of Kernstown put him in a stronger defensive position and allowed Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, General in Chief of the Union Army, to pull reinforcements from Sheridan’s command as needed. Learning of Sheridan’s movement northward, Early was convinced it could mean only one thing, “that Sheridan was preparing to send troops to Grant.”

Lee had sent Early to the Shenandoah Valley in June 1864, determined for it to serve as a diversionary theater of war, needed to keep as many Union troops away from hotly contested Petersburg as possible. With Sheridan’s army now on the move, Early realized he couldn’t stay put. On November 10, the Army of the Valley left its camps near New Market. Interestingly, that same day, a correspondent for The Indianapolis Star projected in an article that Sheridan’s army had not seen the last of Early—unaware of the Confederates’ movement. “Early stands tauntingly” before Sheridan, the correspondent observed. “The Confederate army, that has been again and again sent howling and whirling up the Valley,” could indeed pick up “the little pieces into which it was smashed” and strike.

As the Army of the Valley moved north, few in its ranks, if any, harbored delusions that this would result in a dramatic reversal of fortunes. At this point, the measure of success was not battlefield triumph, but the capacity to incite enough uncertainty among war-planners in Washington, D.C., about Confederate intentions in the Valley to prevent Sheridan from sending any troops to Grant’s aid east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Brigadier General Bryan Grimes, a division commander in Early’s army, wrote to his wife before the departure from New Market: “We leave here to-day to demonstrate against the enemy, to cause them to return with the troops to prevent reinforcement of Grant. If we accomplish that, it will be all that can be expected of us.”

The following day, while Sheridan’s command labored on entrenchments and quarters at their new position, Camp Russell—named in honor of Union Brig. Gen. David Russell, killed at the Third Battle of Winchester (Opequon) on September 19—orders to “Fall in at once” sounded. As recalled by Major John Mead Gould of the 29th Maine, when Confederate soldiers appeared on their front, the mood of Sheridan’s veterans ranged from ambivalence to uncertainty. Acknowledging it was important to remain “alert,” Gould wrote that he “refused to be excited.” On the other hand, Francis Coffin, a veteran of the 30th Maine Infantry, didn’t share Gould’s nonchalance. He was convinced they “were to have another fight for the possession of the valley.”

Outside Camp Russell, however, there seemed little enthusiasm among Early’s men to engage Sheridan. As Confederate artillerist Thomas Henry Carter noted, the Army of the Shenandoah’s “strongly entrenched” position produced “a most uneasy feeling all down the line.” In all probability, Carter wrote, the Confederates “would have given way” had they been engaged by Sheridan’s troops.

Early’s and Sheridan’s soldiers did not come to blows that day, but Union and Confederate cavalry soon did. On November 12, troopers from Union Colonel Alexander Pennington’s brigade engaged portions of Maj. Gen. Thomas Rosser’s command along the Back Road. After a sharp fight, Rosser’s troopers were forced to “give way” and fled “in confusion across Cedar Creek.” Colonel William Powell’s cavalry brigade had similar success against Confederate Maj. Gen. Lunsford Lomax near Nineveh on the Winchester–Front Royal Pike. With his cavalry defeated on both his western and eastern flanks, coupled with the strength of Sheridan’s position, Early that night ordered his command to withdraw south.

“It seems to be now settled”

Although the threat from partisans, irregulars, and bushwhackers would remain until the end of the war, once Early withdrew south without engaging Sheridan’s main force, soldiers in the Army of the Shenandoah were finally able to brim with confidence that Early no longer posed a threat. Early’s unwillingness to engage, coupled with deteriorating weather conditions in mid-November, prompted New Yorker Lewis Foster to write his mother confidently: “There is not much prospects of battle in the Valley this fall. The Johnnies have gone up the Valley.”

Five days after Early withdrew, Colonel Hayes again reached out to his wife: “When I wrote last I was in some doubt whether this Valley campaign was ended or not. It seems to be now settled. Early got a panic among his men and left our vicinity for good.”

Even though Early would remain in the Valley, the bulk of his command did not. On November 15, Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s Division headed to Petersburg. Three weeks later, the divisions commanded by Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon and Brig. Gen. John Pegram followed suit. By mid-December, Early’s command rested near Waynesboro, Va., its strength reduced to about 3,000 men.

George Carpenter, a veteran of the 8th Vermont Infantry, perhaps summed it up best. Until November 12, Carpenter wrote, Early “continued to menace the Shenandoah Valley as the sea lashes the shore after the fury of a storm is spent,” adding that from that point forward, “Old Jube” would “never again…touch the high water mark.”

Jonathan A. Noyalas is director of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute, a professor in the history department at Shenandoah, and the author of numerous books including Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley During the Civil War Era (University Press of Florida, 2021).