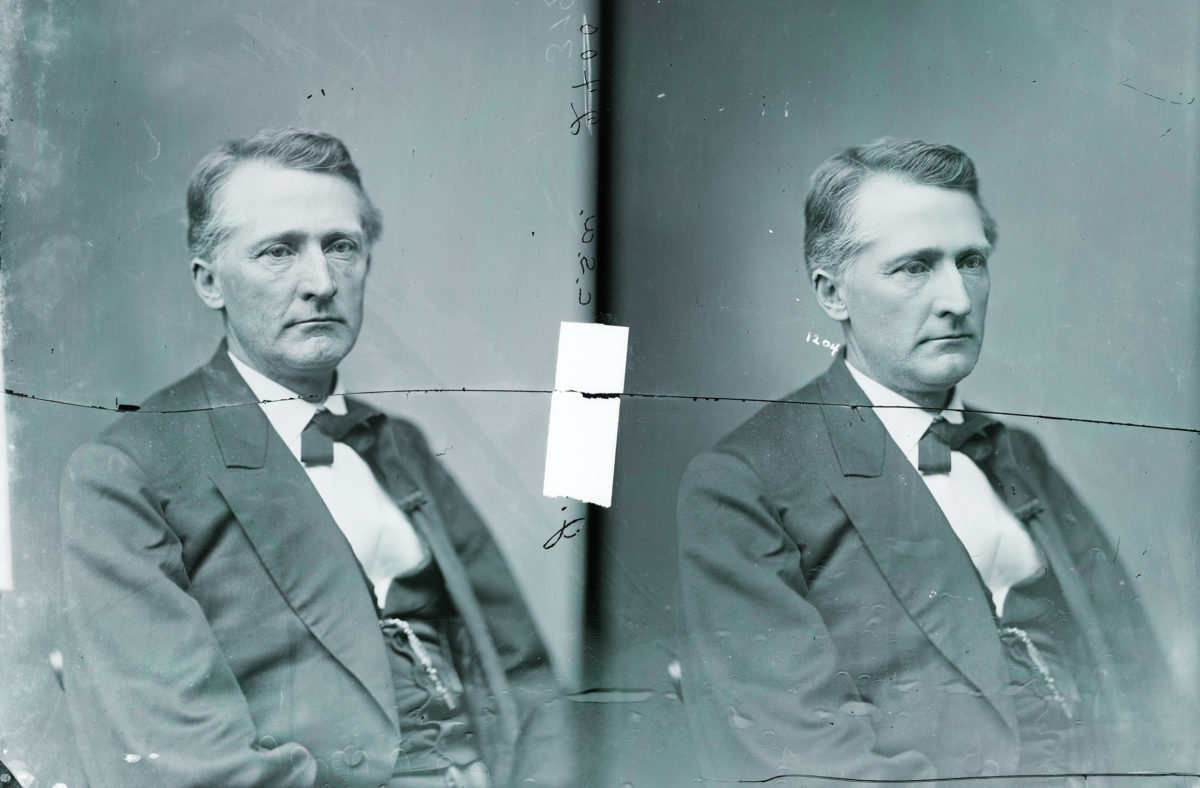

Dubbed “The Gray Ghost,” Col. John Singleton Mosby became a formidable Confederate partisan leader—arguably, next to William Quantrill, the most famous Rebel guerrilla—during the American Civil War. Underestimated in his youth for his small, thin stature, Mosby was a scrappy lad who got expelled from the University of Virginia at age 19 for shooting a bully. He was also highly intelligent, running his own law practice after his release from prison in 1854.

Both Mosby’s aggressive spirit and his cold, calculating mind would serve him well during the war, which he began in a company of mounted infantry. His skills at gathering intelligence were appreciated by famed cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart, under whose auspices he was promoted to the rank of major and put in command of the 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion in 1863.

Under Mosby’s leadership, this partisan outfit became known as “Mosby’s Rangers,” and earned a widespread reputation as a stealthy—and highly dangerous—strike force. They ambushed Union forces in raids far behind enemy lines, disrupted enemy supplies and communications, and committed acts of sabotage in support of Confederate army operations. Some historians acknowledge that Mosby was an early pioneer of unconventional tactics later adopted by U.S. Special Forces.

Mosby survived the war, although he became a target for reprisals following Union victory. Eventually given protection by Ulysses S. Grant, he later became one of Grant’s campaign managers, served as a diplomat and worked as assistant U.S. Attorney General.

Mosby himself was a somewhat flamboyant character known not only for guile but also for his roguish sense of humor, which is manifest in the following excerpt from his 1917 autobiography, The Memoirs of Col. John Singleton Mosby. Drawn from a chapter entitled “First Exploits As A Partisan,” Mosby’s anecdote relates a series of incongruous events in which a Union cavalry force seeking him picks up more civilians than it can handle, Mosby himself, mounted on a strong-willed, runaway horse, accidentally leads a charge, and Union forces flee from their own cavalry.

Apart from Mosby’s sarcastic sense of humor, the narrative also reveals his hardnosed common sense as a soldier in his criticisms of what Union forces did wrong.

“Canterbury Pilgrims”

From our rendezvous along the base of the Blue Ridge [Mountains in western Virginia] we continued to make night attacks on the outposts near Washington [D.C.]. So it was determined in Washington to put a stop to what were called our depredations, and an expedition was sent against us into Loudoun. Middleburg, a village, was supposed to be our headquarters, and it was thought that by surrounding it at night the marauders could be caught…Strategy is only another name for deception and can be practiced by any commander. The enemy complained that we did not fight fair; the same complaint was made by the Austrians against Napoleon.

A Major Gilmer was sent with 200 men in expectation of extirpating my gang—as they called us. He might have done more if he had taken less whiskey along. But the weather was cold! Before daybreak he had invested the town and made his headquarters in the hotel where he had learned that I slept. I had never been in the village except to pass through.

The orders were to arrest every man that could be found, and when his searching parties reported to him, they had a lot of old men whom they had pulled out of bed. Gilmer pretended to think these were the parties that had captured his pickets and patrols and stampeded his camps. If so, when he saw the old cripples on crutches, he ought to have been ashamed.

He made free use of his bottle and ordered a soldier to drill the old men and make them mark time just to keep warm. As he had made a night march of twenty-five miles, he concluded to carry the prisoners to his camp as prizes of war. So each graybeard had to ride double with a trooper. There were also a number of colored women whom he invited, or who asked, to go with him. They had children, but the major was a good-natured man. So each woman was mounted behind a trooper—and the trooper took her baby in his arms. With such encumbrances, sabres and pistols would be of little use, if an attack was made. When they started, the column looked more like a procession of Canterbury Pilgrims than cavalry.

News came to me that the enemy were at Middleburg, so, with seventeen men, I started that way, hoping to catch some stragglers. But when we got to the village, we heard that they had gone, and we entered at a gallop. Women and children came out to greet us—the men had all been carried off as prisoners. The tears and lamentations of the scene aroused all our sentiments of chivalry, and we went in pursuit. With five or six men I rode in advance at a gallop and directed the others to follow more slowly.

I had expected that Major Gilmer might halt at Aldie, a village about five miles ahead, but when we got there a citizen told us that he passed on through. Just as we were ascending to the top of a hill on the outskirts of the village, two cavalrymen suddenly met us. We captured them and sent them to the rear, supposing they were videttes [mounted sentries] of Gilmer’s command. Orders were sent to the men behind to hurry up.

“I Tried To Stop…”

Just then I saw two cavalrymen in blue on the pike. No others were visible, so with my squad I started at a gallop to capture them. But when we got halfway down the hill we discovered a considerable body—it turned out to be a squadron—of cavalry that had dismounted. Their horses were hitched to a fence, and they were feeding at a mill.

I tried to stop, but my horse was high-mettled and ran at full speed, entirely beyond my control. But the cavalry at the mill were taken absolutely by surprise by the irruption; their videttes had not fired, and they were as much shocked as if we had dropped from the sky. They never waited to see how many of us there were. A panic seized them. Without stopping to bridle their horses or to fight on foot, they scattered in all directions. Some hid in the mill; others ran to Bull Run Mountain nearby.

Just as we got to the mill, I saw another body of cavalry ahead of me on the pike, gazing in bewildered astonishment at the sight. To save myself, I jumped off my horse and my men stopped, but fortunately the mounted party in front of me saw those I had left behind coming to my relief, so they wheeled and started full speed down the pike.

We then went back to the mill and went to work. Many had hidden like rats, and as the mill was running, they came near being ground up. The first man that was pulled out was covered with flour; we thought he was the miller. I still believed that the force was Major Gilmer’s rearguard.

All the prisoners were sent back, and with one man I rode down the pike to look for my horse. But I never got him—he chased the Yankees twenty-five miles to their camp.

Fleeing From Themselves

I have said that in this affair I got the reputation of a hero; really I never claimed it, but gave my horse all the credit for the stampede. Now comes the funniest part of the story. Major Gilmer had left camp about midnight. The next morning a squadron of the First Vermont Cavalry [a Union force], which was in camp a few miles away from him, was sent up the pike on Gilmer’s track. Major Gilmer did not know they were coming.

When he got a mile below Aldie, he saw in front a body of cavalry coming to meet him. He thought they were my men who had cut him off from his camp. He happened to be at the point where the historic Braddock road, along which young George Washington marched to the Monongahela, crossed the turnpike.

As Major Gilmer was in search of us, it is hard to see why he was seized with a panic when he thought he saw us. He made no effort to find out whether the force in front was friend or foe, but wheeled and turned off full speed from the pike. He seemed to think the chances were all against him. There had been a snow and a thaw, and his horses sank to their knees in mud at every jump. But the panic grew, the farther he went, and he soon saw that he had to leave some of his horses sticking in the road. He concluded now that he would do like the mariner in a storm—jettison his cargo. So the old men were dropped first; next the negro women, and the troopers were told to leave the babies in the arms of their mothers….

I had not gone far before I met the old men coming back, and they told me of their ludicrous adventure and thanked me for their rescue. They did not know that the Vermont cavalry was entitled to all the glory for getting up the stampede, and that they owed me nothing.

In the hurry to find my horse, I had asked the prisoners no questions and thought we had caught a rearguard. Among the prisoners were two captains. One was exchanged in time to be at Gettysburg, where he was killed. Major Gilmer was tried for cowardice and drunkenness and was dismissed from the army. Colonel Johnstone, who put him under arrest when he got back, said in his report, “The horses returned exhausted by from being run at full speed for miles.” They were running from the Vermont cavalry.