The Partisan Rangers had a big hand in bringing the ‘Gray Ghost’ plenty of glory

John Singleton Mosby will always be regarded as one of the Civil War’s most famous—perhaps infamous—figures, and though he doesn’t quite reside in the war’s pantheon alongside the likes of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Ulysses S. Grant, he assuredly stands as an equal to military history’s “unconventional warfare” legends such as Robert Rogers, Francis Marion, T.E. Lawrence, Orde Wingate, David Stirling, and Aaron Bank. ¶ Mosby, who, it must be noted, was not given his famous sobriquet “The Gray Ghost” until well after the war, was an intelligent, tough, audacious, and innovative leader. He did not invent the concept or techniques of guerrilla warfare, but during the Civil War, he certainly refined and executed them with impressive efficiency and effectiveness.

¶ Mosby’s Partisan Ranger career began in late December 1862 when his commander and mentor, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, “loaned” him the services of nine cavalrymen. This temporary, and informal, command would evolve into the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry—known better as Mosby’s Rangers. By the time Mosby chose to disband rather than surrender the 43rd on April 21, 1865, nearly 800 men had been part of this elite unit. More impressive, roughly 2,000 men would ride in some capacity with Mosby at one time or another during the war. Here are the stories of some of the most memorable of that lot.

William Hibbs

One of the first to join Mosby after he began operations in Northern Virginia was William Hibbs. With a special aptitude for finding forage for the horses in Mosby’s command, Hibbs became the Rangers’ informal “quartermaster.” He was also known as “chief of the corn detail.” It was not an exciting duty nor a particularly prestigious title, but he ensured that the mounts in the command, so essential to its mobility and success, were well fed and healthy.

Hibbs’ unique ability to find forage paid personal dividends, too. He was fond of alcoholic spirits and knew that stockpiles of corn and grains probably indicated a “still” was nearby. Many farms in Northern Virginia had their own private, primitive distilleries. That was important because Mosby, essentially a teetotaler, despised the use of needed forage for the distilling of alcohol—he believed it served a better purpose by feeding horses or soldiers. When Mosby became aware of the location of a still, he had it destroyed. Hibbs, however, developed a system whereby he could find the forage and collect it for the 43rd, locate the still and sample the goods to his heart’s content, and then (only then) return to Mosby with the forage and report the still.

Hibbs had another moniker of which he was exceedingly proud. Born in 1817, he was 20–30 years older than the vast majority of the unit. Younger Rangers called him “Major,” probably a combined result of youthful impertinence and an abiding respect for one’s elders. As John Henry Alexander noted in Mosby’s Men:

Pray don’t make the mistake of assigning William Hibbs among the “non-combatants.” Though his title was merely in courtesy of his quasi office of quartermaster, no braver man followed Mosby. Many years past military age, he rode side by side with his own sons, in the foremost ranks, and his poor maimed and scarred body attested to his familiarity with hot battle.”

Hibbs did revel in the name, and his tombstone in Mount Zion Baptist Church Cemetery in Aldie, Va., is clearly marked “MAJOR Wm. HIBBS”

Henry Cabell “Cab” Maddux

Hibbs’ feats link him with another Ranger, Henry Cabell Maddux, born on July 17, 1848, and nicknamed “Cab.” On February 20, 1864, still just 15 years old, Maddux was leaving a boy’s academy in Upperville, Va., his school books in his hand, when a group of Union cavalrymen came galloping through town. Just behind them were members of Mosby’s Rangers, a cadre that caught Cab’s eye. The youngster looked down at his books and, without another thought, tossed them aside, leapt upon his horse hitched up outside the school, and joined the chase. He became a Ranger that day and remained with them until the end of the war.

Hibbs’ feats link him with another Ranger, Henry Cabell Maddux, born on July 17, 1848, and nicknamed “Cab.” On February 20, 1864, still just 15 years old, Maddux was leaving a boy’s academy in Upperville, Va., his school books in his hand, when a group of Union cavalrymen came galloping through town. Just behind them were members of Mosby’s Rangers, a cadre that caught Cab’s eye. The youngster looked down at his books and, without another thought, tossed them aside, leapt upon his horse hitched up outside the school, and joined the chase. He became a Ranger that day and remained with them until the end of the war.

“That day was the boy’s last at school,” John Munson wrote in Reminiscences of a Mosby Guerrilla: “…[U]ntil the end of the war, he was one of the gamest and best soldiers Mosby had. He was…known to every man in the Command and to everybody in that country, as a fighter.”

Even then, the 5-foot-5 Cab was heavyset. In his later years, he would weigh 450 pounds and be recognized in some newspapers as “the largest man” in Virginia. The youngster’s size made him a good target for the enemy, which is how the tales of Cab Maddux and Major Hibbs intersected along the banks of the Potomac River on July 30, 1864.

According to James J. Williamson’s Mosby’s Rangers: A Record of the Operations of the Forty-third Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, From Its Organization to the Surrender:

We then pushed on up the river to reach the ford at Noland’s Ferry [sic] before another detachment of Yankees, who were coming down the river, should get there. We barely made it, too. I crossed over with the prisoners among the first. But the enemy came up in time to make it hot for our rear guard. Cab Maddux…made a rather attractive mark, but as the bullets were splashing the water around him, his characteristic solicitude for others was manifested. Seeing a comrade in arms struggling through the waves some distance off and not receiving that attention from the Federal soldiers which he thought due to his rank, Cab cried out at the top of his voice, “Hurry up, Major Hibbs! Come along, Major!” The Yankees at once transferred their shower baths from Cab to the Major, who showed his appreciation of the former’s self-sacrifice by spluttering out to him that he was “—respectful all at once.”

Cab had earned Hibbs’ ire, but his playful exuberance created an even bigger quandary for himself on October 14, 1864, during the famed “Greenback Raid,” when Mosby’s men derailed a train on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in Jefferson County, W.Va., seizing $172,000 in paper currency from two Union army paymasters. This time, Cab angered Mosby.

As the Gray Ghost related in The Memoirs of Colonel John S. Mosby:

While we were helping the passengers to climb the steep bank, one of my men, Cab Maddux, who had been sent off as a vidette to watch the road, came dashing up and cried out that the Yankees were coming. I immediately gave orders to mount quickly and form, and one was sent to find out if the report was true. He soon came back and said it was not. The men then dismounted and went to work again. I was very mad with Cab for almost creating a stampede and told him that I had a good mind to have him shot. Cab was quick-witted, but, seeing how angry I was, said nothing then. But he often related the circumstance after the war. His well-varnished account of it was that I ordered him to be shot at sunrise, that he said he hoped it would be a foggy morning, and that I was so much amused by his reply that I relented and pardoned him. Years afterwards Cab confessed why he gave the false alarm. He said he heard the noise the train made when it ran off the track and knew the men were gathering the spoils and did not think it was fair for him to be away picketing for their benefit. He also said that after he got to the burning cars he made up for lost time.

» John Atkins

The 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry primarily comprised Virginians and a contingent of Marylanders. It also had at least three foreigners within its ranks. One, John Atkins, crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Ireland to join Mosby. His brother, Robert, had preceded him to America and first served in Wheat’s Battalion (the famed “Louisiana Tigers”). Robert later became Maj. Gen. Arnold Elzey’s aide-de-camp before returning to Ireland in 1864.

John Atkins was mortally wounded during the Rangers’ fight against the 8th Illinois Cavalry on October 29, 1864, near Upperville, Va. His last words were: “I have come three thousand miles to fight for the Confederacy, but it is all over now. My poor mother—Jesus have mercy on her soul!” Upon seeing Atkins’ body, Mosby reportedly said, “There lies a man I would not have given for a whole regiment of Yankees.”

Atkins is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere near Paris, Va.

» Baron Robert von Massow

Baron Robert von Massow (Baron Robert August Valentin Albert Reinhold von Massow, to be exact) arrived in Richmond in July 1863. A lieutenant in the Prussian army, he had come in search of adventure with Confederate forces. With a recommendation from J.E.B. Stuart, Massow joined Mosby.

Once, while chasing a fleeing detachment of Union cavalry, Massow supposedly exclaimed, “This is more fun than a fox hunt!” On another occasion, when a group of Rangers had surreptitiously slipped into a stable containing Union horses with the intention of capturing them, Massow expressed his disgust by saying, much too loudly, “This is not fighting, this is horse stealing!” Between the chuckles and shock at his noisy outburst, the other Rangers were able to quiet him.

Once, while chasing a fleeing detachment of Union cavalry, Massow supposedly exclaimed, “This is more fun than a fox hunt!” On another occasion, when a group of Rangers had surreptitiously slipped into a stable containing Union horses with the intention of capturing them, Massow expressed his disgust by saying, much too loudly, “This is not fighting, this is horse stealing!” Between the chuckles and shock at his noisy outburst, the other Rangers were able to quiet him.

The Rangers preferred carrying multiple revolvers as their weapons of choice and believed that sabers were rattling nuisances. Massow, however, was a firm believer in the effectiveness of a saber, and it remained his weapon of choice. Ranger Ben Palmer once saw Massow starting a raid with his trusted saber by his side and asked him in complete seriousness, “Do you want to be killed?” To which Massow replied, “A good soldier is always prepared to die!”

After his first fight with the Rangers, Massow was upset, according to a fellow Ranger, that he had not been wounded—he apparently hoped to return to Prussia with a wartime memento. On February 22, 1864, during a fight at Anker’s Shop (Second Dranesville) in present-day Sterling, Va., Massow got that wish, though not in a manner he could celebrate.

In that clash, Mosby and about 150 men ambushed and then attacked a 300-man detachment of the 2nd Massachusetts and 16th New York Cavalry regiments. During the ensuing melee, Massow was riding down on the Union commander, Captain James Sewell Reed, with his saber poised for a lethal strike. Reed, taking quick note of his predicament, threw up his arms to indicate his surrender. Massow waved Reed to the rear to await his fate as a prisoner and then began to ride by Reed in search of another target. As Massow passed Reed, the Union captain shot him in the back and out of the saddle.

Reed was then killed by another Ranger, William Chapman.

The dangerously wounded Massow was evacuated from the field and treated. He survived but endured a long and difficult recovery that kept him from returning to Mosby’s command. He soon returned to Prussia. By 1890, he had the supreme command of the Prussian cavalry. In 1899, he was appointed general of the army. In 1906, after nearly 54 years of military service, he retired. He died in 1927 in Germany.

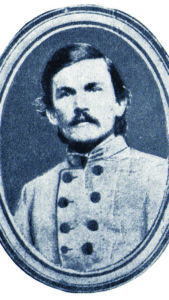

» Bradford Smith Hoskins

Another Ranger, Englishman Bradford Smith Hoskins, was not as lucky.

Born in 1833 in Bishops Taskbrook, Warwickshire, Hoskins joined the British Army’s 44th Foot as a lieutenant and in 1854 served in the Crimean War, where he took part in some of the fiercest fighting. He was promoted to captain in 1855 and returned to England that same year. In recognition of his service, Hoskins was awarded the Crimea War Medal with clasps for Alma, Inkermann, and Sebastapol. Within a few years, Hoskins left the Army.

Born in 1833 in Bishops Taskbrook, Warwickshire, Hoskins joined the British Army’s 44th Foot as a lieutenant and in 1854 served in the Crimean War, where he took part in some of the fiercest fighting. He was promoted to captain in 1855 and returned to England that same year. In recognition of his service, Hoskins was awarded the Crimea War Medal with clasps for Alma, Inkermann, and Sebastapol. Within a few years, Hoskins left the Army.

He was still in search of adventure, however, and traveled to Italy in 1860 to join the forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi in the struggle to unify Italy. After a brief stay, he returned to England in 1861.

Hoskins did not lose his sense of wanderlust and ventured to Canada late in 1861. While there, he wrote a 24-page pamphlet titled “A Few Thoughts on Volunteering” that espoused the virtues of a volunteer army.

In 1862, still not comfortable remaining in one place for too long, Hoskins left Canada for the United States and “settled” in Baltimore, Md. In Baltimore, he became involved in smuggling goods into the Confederacy and subsequently made his way farther south, joining Mosby’s command in March 1863. He saw action with the Rangers at Miskel’s Farm on April 1, 1863, and at Warrenton Junction on May 3. Hoskins was quite conspicuous during those engagements, clad in the scarlet uniform of his British Army days and wielding a saber.

On May 30, 1863, the Rangers derailed and attacked a train near Catlett’s Station, Va. The raid began as a complete success and the Rangers were having a bit of a frolic as they ransacked the train looking for loot. They, Mosby especially, had not factored in a large and rapid response from Union cavalry in the area as elements of the 7th Michigan Cavalry, 5th New York Cavalry, and the 1st Vermont Cavalry all converged on Mosby and forced the Rangers to begin a fighting withdrawal.

Once the immediate danger posed by the Union response had decreased slightly, Mosby stopped his men near Grapewood Farm (near today’s Vint Hill Farms area in Warrenton). He decided if the enemy insisted on pushing the Rangers, they would pay dearly for their aggressiveness.

Mosby placed a mountain howitzer he had taken with him on the raid at the top of a small rise on a road up which the Union cavalry would have to attack. He formed a group of his best fighters around the gun and prepared to make what amounted to a last stand. Hoskins was one of the men in the group.

The struggle ebbed and waned, but sheer numbers on the Union part and dwindling ammunition on the Rangers’ part soon tilted the fight in favor of the Northerners. A Union trooper rode up on Hoskins. Hoskins threatened him with his saber and said, “Surrender, you damn Yankee.” The Union soldier replied, “The hell I will,” and shot Hoskins in the neck and back. The remaining Rangers fled, leaving Hoskins lying on the field in a pool of his own blood.

Later, an Englishman named Charles Green who lived nearby in the small town of Greenwich, Va., found Hoskins and took him to his home.

Hoskins died on June 2, 1863, and was buried in the Greenwich Presbyterian Church’s cemetery. “He was a brave soldier, and had made many friends while with the command,” fellow Ranger James J. Williamson declared in tribute.

» The Chapman Brothers

A cursory review of unit rosters from both sides during the war reveals many family connections. The makeup of Mosby’s Rangers was no different. There were at least four father/son teams in the 43rd Battalion and a very large assortment of brother and cousin combinations. One particular set of brothers—the Chapmans—stands out.

Samuel “Sam” Forrer Chapman, born in 1838, and his brother, William Henry Chapman, born in 1840, both joined the Confederate Army early in the war and were members of Virginia’s famed Dixie Artillery by the end of 1861.

The reorganization of the Confederate Artillery in 1862 caused the official disbanding of their unit on October 4 and the reassignment of the brothers to recruiting officer duty in Virginia’s Fauquier County. It was a position both detested.

Fortunately, for the disgruntled Chapmans, John Mosby began his unconventional operations in early 1863 in close proximity to where the Chapmans were stationed. They participated in his raids as often as possible.

Both Sam and William were involved in the Rangers’ fight at Miskel’s Farm on April 1, 1863. Sam provided Mosby with an indelible memory that the Gray Ghost shared in his Mosby’s War Reminiscences and Stuart’s Cavalry Campaigns:

There was with me that day a young artillery officer—Samuel F. Chapman—who at the first call of his State to arms had quit the study of divinity and become, like Stonewall Jackson, a sort of military Calvin, singing the psalms of David as he marched into battle. I must confess that his character as a soldier was more on the model of the Hebrew prophets than the Evangelist or the Baptist in whom he was so devout a believer. Before he got to the gate Sam had already exhausted every barrel of his two pistols and drawn his sabre. As the fiery Covenanter rode on his predestined course the enemy’s ranks withered wherever he went. He was just in front of me—he was generally in front of everybody in a fight—at the gate. It was no fault of the Union cavalry that they did not get through faster than they did, but Sam seemed to think that it was. Even at that supreme moment in my life, when I had just stood on the brink of ruin and had barely escaped, I could not restrain a propensity to laugh.

Sam, to give more vigor to his blows, was standing straight up in his stirrups, dealing them right and left with all the theological fervor of Burly of Balfour. I doubt whether he prayed that day for the souls of those he sent over the Stygian river. I made him a captain for it.

Sam was grievously wounded in the Grapewood Farm Fight in Auburn, Fauquier County, (where Hoskins had been mortally wounded) and paroled on the field by the victorious Union cavalry. The wound, though serious and painful, had a positive aspect. While recuperating, Sam fell in love with his future wife, Eliza Rebecca “Miss Beck” Elgin. They were married on June 28, 1864, the same day Sam gained the rank of captain and assumed command of Company E of the 43rd Battalion.

After the war, Sam was the chaplain of the African-American 4th Immune Regiment in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, became the superintendent of public schools in Virginia’s Allegheny County, and served as the deputy U.S. marshal for the Western District of Virginia in 1909. He and Mosby remained close friends and communicated frequently until Mosby’s death in 1916.

William Henry Chapman surpassed his older brother’s wartime career. He rose through the officer ranks of Mosby’s Rangers, eventually assuming the rank of lieutenant colonel and became second only to Mosby in command of the unit. Mosby noted William in dispatches for conspicuous gallantry at least twice.

William also fell in love with a young lady, Josephine Jeffries, living in Mosby’s Confederacy. He was a rather dour and taciturn individual, but Jeffries, whom he married on February 25, 1864, evidently coaxed a softer persona out of him.

Following General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, Mosby tasked William with leading a negotiating team to meet with Union authorities about specific terms for surrender. The meeting ended without an agreement.

On April 21, 1865, Mosby disbanded rather than surrender the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry in Salem, Va. (today Marshall). Taking along a small contingent of Rangers, Mosby decided to travel south in hopes of linking up with General Joseph Johnston and continue fighting. The sad task of leading the remainder of the command to Winchester, Va., to seek wartime paroles fell to Mosby’s No. 2, Chapman.

After the war, William Chapman became an Internal Revenue Service agent—a “Revenuer” who ferreted out hidden, illegal alcohol stills. Never wounded during the war, Chapman ironically received his first-ever gunshot at the hands of a tax-evading moonshiner. He survived, however, living until 1929.

According to Chapman’s obituary in the Greensboro (N.C.) Daily, published September 7, 1929:

General [Winfield Scott] Hancock, to whom Colonel Chapman surrendered his command, was so impressed by the spirit of the young Confederate that he wrote in his report that in healing the wounds of war and reuniting the country “This young man will be valuable to the government.” The prophecy was fulfilled in a life of devotion to the interests of the south without bitterness toward his former foes….

He had an exceptionally large number of devoted friends and admirers. Yesterday a friend paid this tribute: “A man of exemplary character and spotless integrity, Colonel Chapman lived a life of simple and natural religion. He kept the faith received at his mother’s knee and walked with God every day. Death had no terror for him. He had faced it a thousand times. He was going home to meet the Savior whom he served and to meet the beloved wife whose presence could not but enhance the glory of heaven itself for him.

Eric Buckland retired from the U.S. Army as a lieutenant colonel after spending the majority of his 22-year career in Special Forces. An officer of the Stuart–Mosby Historical Society in Centreville, Va., Buckland has written several books and frequently delivers presentations focused on the “men who rode with Mosby.” He can be contacted at info@mosbymen.com.

_____

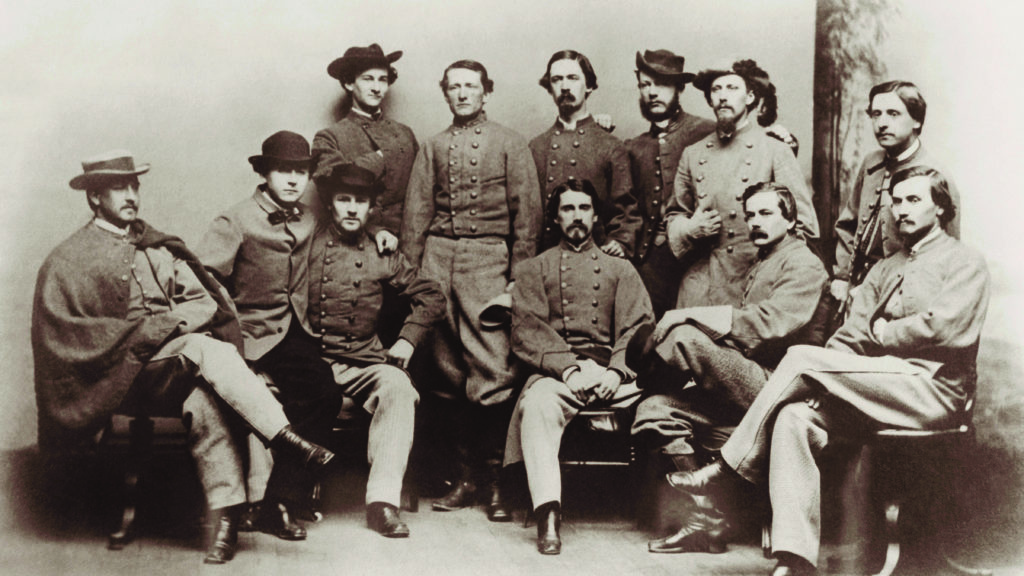

Who Were They?

JAMES MONROE HEISKELL, Private, Company C

Great-grandson of President James Monroe. Served with the 1st Maryland Cavalry before joining Mosby’s Rangers. Captured on January 4, 1865, and sent to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, from which he was released on June 13, 1865. Worked for several years as the clerk of the Court of Common Pleas in Baltimore, and as a U.S. Army paymaster in 1888. Died October 8, 1899. Buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y.

2. HENRY B. SLATER, Private, Company D

Served in the 1st Maryland Cavalry before joining Mosby. Younger brother of Ranger George Meacham Slater. Captured on January 4, 1865, along with James Heiskell, and sent to Fort Warren. Released on June 15, 1865. Committed suicide on August 31, 1874, by slitting his throat with a straight-edged razor.

3. DANIEL MURRAY MASON, 4th Corporal, Company E

Born on December 13, 1843. Grandson of Founding Father George Mason. Served in the Fauquier (Va.) Artillery before transferring to Mosby’s Rangers. Paroled in Winchester, Va., on April 22, 1865. Died July 8, 1869.

4. CLAIBORNE ROBINSON, Private, Company D

Lived in Baltimore after the war. No further information available.

5. JOHN SINGLETON MOSBY, Colonel

Enlisted as a private in the Washington (Va.) Mounted Rifles on May 14, 1861. Promoted to 1st lieutenant on April 2, 1862, and served as adjutant of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Resigned his commission on April 23, 1862, and became a scout for Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Began Partisan Ranger career in January 1863 with nine men “loaned” to him by Stuart. Attended the University of Virginia prior to the war. Lawyer. Appointed as U.S. consul to Hong Kong and served in that capacity from 1878 to 1885. Attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1885-1901. Served in the U.S. Department of Interior and Department of Justice. Died May 30, 1916.

6. CHARLES EDWARD GROGAN, 1st Lieutenant, Company D

Author McHenry Howard referred to Grogan as “having as little sense of fear and danger as any man he had ever seen.” Captured at Gettysburg while serving on Maj. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s staff and sent to the Johnson’s Island POW camp in Ohio. After escaping from Johnson’s Island, he joined Mosby’s command. Served as bailiff at the Court House in Baltimore for more than 20 years. Died January 1, 1922.

7. HARRIS CHAMBERLAIN BLANCHARD, Private, Artillery Company

Reportedly a prosperous and well-known architect in New York City after the war. But in the summer of 1901, his whereabouts became unknown; then he was found after six weeks wandering the streets of the city suffering severely from exposure. He was admitted to the insane ward at Bellevue Hospital in August. In 1904, he was recorded residing at the Maryland Line Confederate Soldier’s Home in Baltimore.

8. DANIEL GIRAUD WRIGHT, Private, Company D

Born in Rio de Janeiro and attended the University of Virginia from 1857 to 1861. Served during the war in the 21st Virginia Infantry, 1st Maryland Infantry, and 1st Virginia Cavalry prior to joining Mosby in December 1863. He was captured in April 1864 and spent the remainder of the war at Fort Warren. After the war he practiced law and was a judge on the Supreme Bench of Baltimore for 22 years. In 1871, he married Louisa Sophia Wigfall, the daughter of Senator Louis Trezevant Wigfall (a former member of both the U.S. and Confederate senates). Louisa, known as “Luly,” is remembered for her book A Southern Girl in ‘61: The War-Time Memories of a Confederate Senator’s Daughter.

9. J. HENLEY SMITH, Private, Company D

Great-grandson of John Henley, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Attended Princeton University prior to the war. In his will, he donated to the Library of Congress a vast collection of letters written by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, James Madison, and other notables in American history. The letters had been from correspondence his grandmother had conducted with those luminaries. His will also instructed that $25,000 be given to Princeton to establish and maintain scholarships in his family’s honor. The scholarships continue to be awarded to this day. Postwar, he was treasurer of the Washington Monument Society and a member of the Columbia Historical Society.

10. JOSHUA WARFIELD RIGGS, Private, Company D

Served in the 1st Virginia Cavalry and the 1st Maryland Cavalry prior to joining Mosby. He was a postwar merchant in both Baltimore and Indianapolis. Organized the 1897 Mosby Ranger Reunion in Baltimore. He was a member of the Royal Arcanum. He died January 10, 1898.

11. ALEXANDER GIBSON CAREY, Private, Company E

Brother of Ranger James Carey. He was connected with the wholesale drug firm of James Bailey & Son in Baltimore after the war. He died September 9, 1917.

12. GRESHAM HOUGH, Private, Company D

Served in the 1st Maryland Infantry and 1st Maryland Cavalry before joining Mosby in 1864. Attended College of William & Mary in 1860-61. Uncle of future Princeton football hero John Prentiss Poe Jr. Died October 11, 1891, in New York.

This story appeared in the July 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.