“I used to watch planes as a teenager and fantasize about being in the cockpit.”

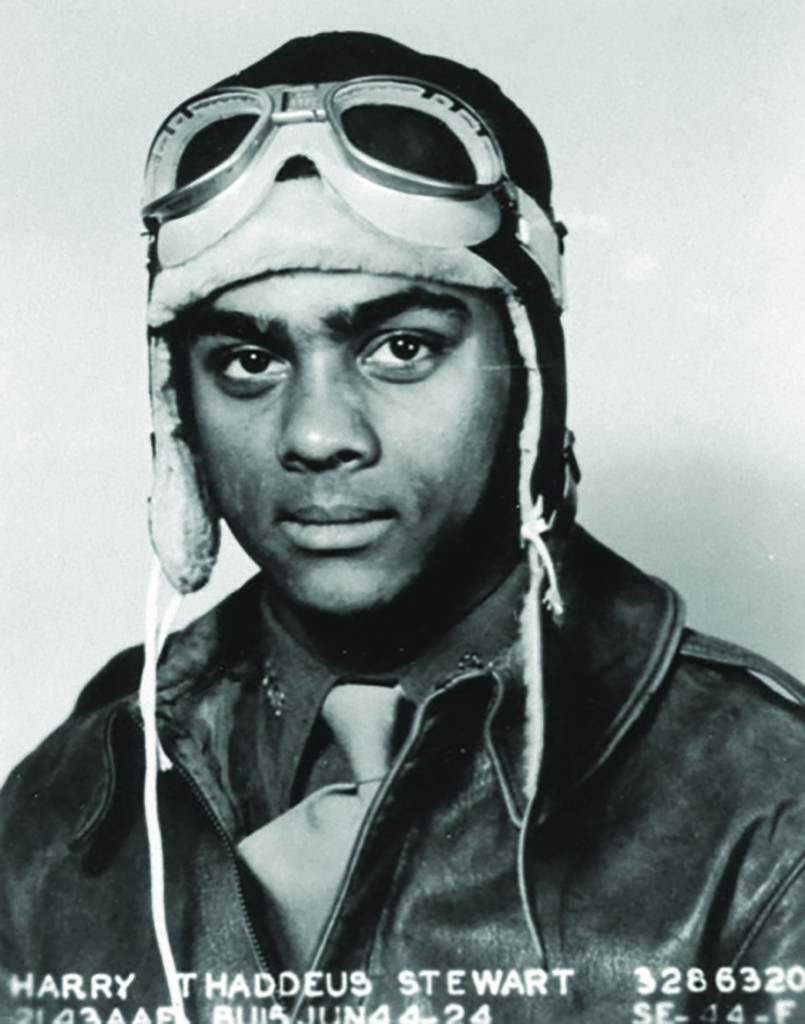

AT 95, HARRY STEWART is sharp-minded, amiable, and talkative. There is a kindness in his voice that belies his achievements: 75 years earlier, Stewart was flying P-51 Mustangs over Europe with the fabled “Red Tails,” the 332nd Fighter Group made up of African American pilots in the then-segregated U.S. military. He flew 43 combat missions—scoring three kills, all in one day—while escorting and protecting heavy bombers to their targets. While Stewart encountered racism throughout his flying career, he has maintained a positive attitude that helped propel him to top positions as an engineer and company executive. Stewart is the subject and collaborator of a new book by Philip Handleman, Soaring to Glory: A Tuskegee Airman’s Firsthand Account of World War II.

Have you always wanted to fly?

My parents told me that when I was two years old in Virginia, I would crane my neck in my crib to look at planes taking off from nearby Langley Field. They said I would coo as they went by. My folks later moved to the borough of Queens in New York City. We lived about a mile from North Beach Airport, now known as LaGuardia. I used to go over there as a teenager and watch the planes. I would fantasize about being in the cockpit. I didn’t realize then that a few years later I would be sitting in the cockpit of a real plane. It was the fortune—or misfortune—of war that brought that about.

Were you drafted into the military?

I wanted to beat the draft and get into the Army Air Corps as a pilot trainee, my heart’s desire. I took the examination for aviation cadet in 1942 when I was 18 years old. After basic training at Keesler Army Airfield in Mississippi, I went to the segregated air base at Tuskegee, Alabama, and continued training there. A year and a few months later, I was sitting in the cockpit with my second lieutenant’s bars, flying my plane.

Segregation and racism were a part of the military and society back then. How did you deal with it?

After I joined the army, I was crossing the Mason-Dixon Line going from New York to the South on a train. The conductor pointed to me and said I had to go in the colored car. It was a hard thing to swallow, but I did because I had my eyes on the prize—and that was getting my wings. There may have been some bumpy roads in the past, but I always look toward the future.

My first unit was the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the U.S. Army Air Forces’ first African American fighter squadron. I got to fly with the Red Tails—the 332nd Fighter Group, under the Fifteenth Air Force—in January 1945.

The Red Tails had a reputation for staying with their bombers. Why was that?

That was the result of our commanding officer, Colonel Benjamin O. Davis Jr., an African American who retired in 1965 as a lieutenant general. He was later promoted to four-star general. At the time, he admonished us on nearly every mission to stay with the bombers: “Gentlemen, you protect the bombers and those people onboard them. You are to interdict with any aircraft coming in, but then you return to the bombers.” It was under the penalty of court-martial if you decided to hot dog to get some enemy kills.

You scored three kills on one mission. Tell us about that day.

That was a day I can’t forget. It was April 1, 1945, which happened to be Easter Sunday and also April Fools’ Day. We were on a bomber escort mission into Austria. We were given permission by Colonel Davis and the Fifteenth Air Force Command to leave the bombers after they delivered their payloads so we could destroy targets of opportunity: river barges, rolling stock on the roads and rail lines, and engaging enemy fighter aircraft.

We went on this sweep and ran into a horde of German Focke-Wulf 190-Ds—a very fine aircraft. Three of our seven planes were shot down. One of the pilots made it back to friendly territory, another was killed instantly, and the third, Walter Manning, managed to bail out of his crippled aircraft. When he alighted on the ground near Linz, Austria, he was captured. Then a mob beat him severely and lynched him from a lamppost. It was horrible, but it was not unique. The Austrians hanged numerous Allied airmen. Not only American, but British, Canadian, South African, and others. The Austrians suffered terrible bombings, and they wanted revenge.

What happened to you?

I managed to sneak up behind two Fw 190s and hit both of them, one at a time. I don’t think either one saw me. With the third aircraft, I saw these tracers come by and realized he was behind me. I thought I had had it. He had me dead to rights. I panicked and dove to the ground. I was pulling my aircraft in and making some extremely tight turns, dangerous maneuvers. The German pilot, in trying to follow me, over-controlled and hit the ground. His aircraft was destroyed and the Fifteenth Air Force decided to give me credit for it, even though I didn’t shoot him down.

What was it like flying a fighter in combat?

An ace pilot was asked that question. “Sheer boredom interspersed with moments of terror,” he said. That’s a good description. My greatest fear was being trapped in the aircraft when it was on fire. That gave me nightmares. Being a long-range escort, we were loaded down with fuel. We had two 110-gallon external fuel tanks, 90-gallon internal fuel tanks in each wing, and 85 gallons in the fuselage sitting right behind you. On takeoff, everything depended on the Mustang’s Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. One miscue and you go down in a big orange mushroom and it’s all over.

How did the Mustang fly?

It was thrilling. It was like you had been driving a jalopy around and somebody comes up and asks, “Would you like to get in this Maserati?” It was beautiful. It was really a pilot’s aircraft—very responsive to commands. It was like an extension of your own body. The wings became your arms and the rudder pedals your legs and the fuselage your body. It was like you had melded into one machine.

Where were you when the war in Europe ended?

I was in my tent in England and I heard it on the radio. I said, “Well, I guess my next tour will be Okinawa.” The Tuskegee Airmen at home were being trained to fly B-25 bombers. I think there was a master plan to convert us to a combined group of bombers and fighters and send us to Okinawa, where we would fly to Japan and the fighter pilots of the 332nd would serve as escorts. We probably would have been flying the F-82—the Twin Mustang. It had a tremendous range. We might have flown the P-47N Thunderbolt. Both those planes had maybe a 13-hour endurance, which was enough to take us to the Japanese mainland and back again. But, of course, they dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and that ended any prospects of us being sent to the Pacific.

What happened after the war?

The crowning glory was in 1949 when Hoyt Vandenberg, the air force chief of staff at the time, said he wanted to resurrect a competition held before World War II, the Fighter Gunnery Meet. He directed that all fighter groups in the continental United States would send three pilots to compete in the deserts near Las Vegas.

The Tuskegee Airmen competed in aerial gunnery at 10,000 and 20,000 feet, strafing, skip-bombing, dive-bombing, rocketry. We were divided into two groups: one was the jet class and the other was the piston class. There were seven fighter groups represented in the jet class and five in the piston class. The Tuskegee Airmen won the piston class. We were the first Top Guns, postwar, as far as the piston class was concerned. We were flying P-47s against P-51s, and we were able to best them! The big thing it demonstrated was that the African American pilots were on par with the other pilots, and having a segregated group was wasteful as far as manpower went. One month after that, the 332nd Fighter Group was completely disbanded and personnel were sent to all four corners of the Earth. Since then, the U.S. Air Force has been completely integrated.

You wanted to become a commercial airline pilot, but racism ended that dream.

I did apply to the airlines when I got out of the service in 1950 but was turned down. It was maybe a decade later that the airlines recanted their policy and took on black aircrew members. Recently, I was flying somewhere and I happened to look in the cockpit. Lo and behold, the pilot and copilot were African American—and both were female! That brought tears to my eyes.

You resumed flying when you were in your sixties. Did you ever fly a P-51 again?

Just last year, I was at an air show and somebody had a two-seater P-51 with dual controls. The pilot took me up and said, “You got it.” I thought, “Well, he’s the pilot. If I get in trouble, I know he can get me out of it.” I did a roll, a loop, and an Immelmann turn. Those three maneuvers took all of the temper out of me. But it was like bicycle riding. I felt quite comfortable up there. At 95, it still feels good! ✯

This article was published in the April 2020 issue of World War II.