New Orleans native Jerome Smith can still connect with the anger he felt that evening more than 50 years ago when he tore into U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

“Kennedy was a cold-blooded politician. He had no real interest in the salvation of me or my people or anything else,” Smith said in an interview. “I told him he was addicted to power. He would do anything to keep it.”

Growing up, Smith loved books, but at school in the Tremé district, he only got to read used volumes. When, as a boy, he tried to enter a public library, a policeman punched him in the chest.

On the St. Charles streetcar, he and other African-Americans had to sit behind screens so that white passengers wouldn’t have to look at them. On one standing-room trip in 1949, Smith wanted to get off his feet. He pitched a streetcar screen to the floor and took a forbidden seat.

“This was not in the context of protest, I just wanted to sit down,” he said. “The white people and the conductor all went crazy—remember, this is before Rosa Parks.”

When white passengers started coming for him, a black passenger grabbed him. “She slapped me up the side of my head and told the white folks she would take me home and beat me for disrespecting them,” Smith said. His rescuer took him off the car. “She hugged me and she was crying. And she told me to never stop.”

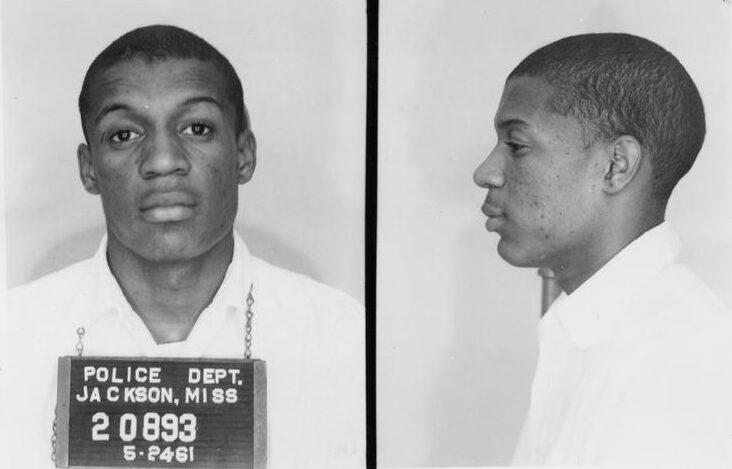

In 1960, Smith, 21, joined civil rights marches and sat in at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Arrested for trying to desegregate a McCrory’s lunch counter, he spent a month in the parish jail. He became an organizer for the Congress of Racial Equality.

In May 1961, the Freedom Ride movement began challenging the segregation of public transportation accommodations like bus station restaurants and waiting rooms. Smith signed up. That November, he and compatriots boarded a bus bound from New Orleans to McComb, Mississippi.

“When we entered the McComb bus station, all these white folks came pouring into the station shouting ‘N——s!’ and ‘Kill ’em!’ They were beating us with brass knuckles and fists and sticks. I was being overwhelmed by some folks and my friend George Raymond intervened. He pretty much saved my life. He enabled me to remove myself from a danger zone while he absorbed the beating.”

In spring 1963, Smith was in New York City getting treatment for those injuries at Lenox Hill Hospital when he was asked to join other activists at an impromptu event being organized by writer James Baldwin. The group was to meet May 24 to discuss civil rights with Robert F. Kennedy.

Smith accepted the invitation and appeared as instructed at an apartment on Central Park South. As the nation’s chief law enforcement official was enumerating data on Justice Department progress regarding civil rights, Smith grew angry. The attorney general appeared to see progress in terms of statistics.

The 24-year-old New Orleans activist had held back as long as he could, but suddenly shattered the calm, his stammer underlining his anger.

“Mr. Kennedy, I want you to understand I don’t care anything about you and your brother,” Smith began. “I don’t know what I’m doing here, listening to all this cocktail party patter.”

The real threat to white America wasn’t the Black Muslims, Smith insisted—it was when he and other advocates of nonviolence lost hope. Smith’s record made his words resonate. As a Freedom Rider and CORE organizer, he had suffered as many savage beatings as any civil rights protester had, including one for which he was now getting medical care in New York.

But his patience and his pacifism were wearing thin, he warned. If the police came at him with more guns, dogs, and hoses, he would answer with a weapon of his own.

“When I pull a trigger, kiss it goodbye,” Smith said.

Kennedy was shocked, but Smith wasn’t through. Not only would young blacks like him fight to protect their rights at home, he said, they would refuse to fight for America in Cuba, Vietnam, and any of the other places where the Kennedys saw threats.

“Never! Never! Never!” Smith declared.

“You will not fight for your country?” asked the attorney general, who had lost one brother and nearly a second at war. “How can you say that?”

Smith replied that just being in the room with Kennedy made him nauseous. Others chimed in, demanding to know why the government couldn’t get tougher in taking on racist laws and ghetto blight.

Lorraine Hansberry, author of the play A Raisin in the Sun, stood to say she was sickened as well.

“You’ve got a great many very, very accomplished people in this room, Mr. Attorney General, but the only man who should be listened to is that man over there,” Hansberry said, pointing to Smith.

Three hours into the evening, the dialogue had become a brawl, with Smith setting the tone.

“He didn’t sing or dance or act. Yet he became the focal point,” said Baldwin. “That boy, after all, in some sense, represented to everybody in that room our hope. Our honor. Our dignity. But, above all, our hope.”

“Kennedy had only a numerical relationship with what was going on, and no comprehension, Smith said, “I felt a sense that we were losing because so many folk had been banged up all over the South. It was a bad, bad situation.”

Kennedy would not understand what it meant to be black in America “until tragedy knocks on your door,” Smith told him. Six months later, it did.

“After Robert Kennedy lost his brother, he had that sense of loss, and he began to understand,” Smith, 77, said recently. “I think he would have made a great president.”

This story is supplemented with material from the book Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon by Larry Tye. Copyright @ 2016 by Larry Tye. Reprinted by arrangement with RandomHouse, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.