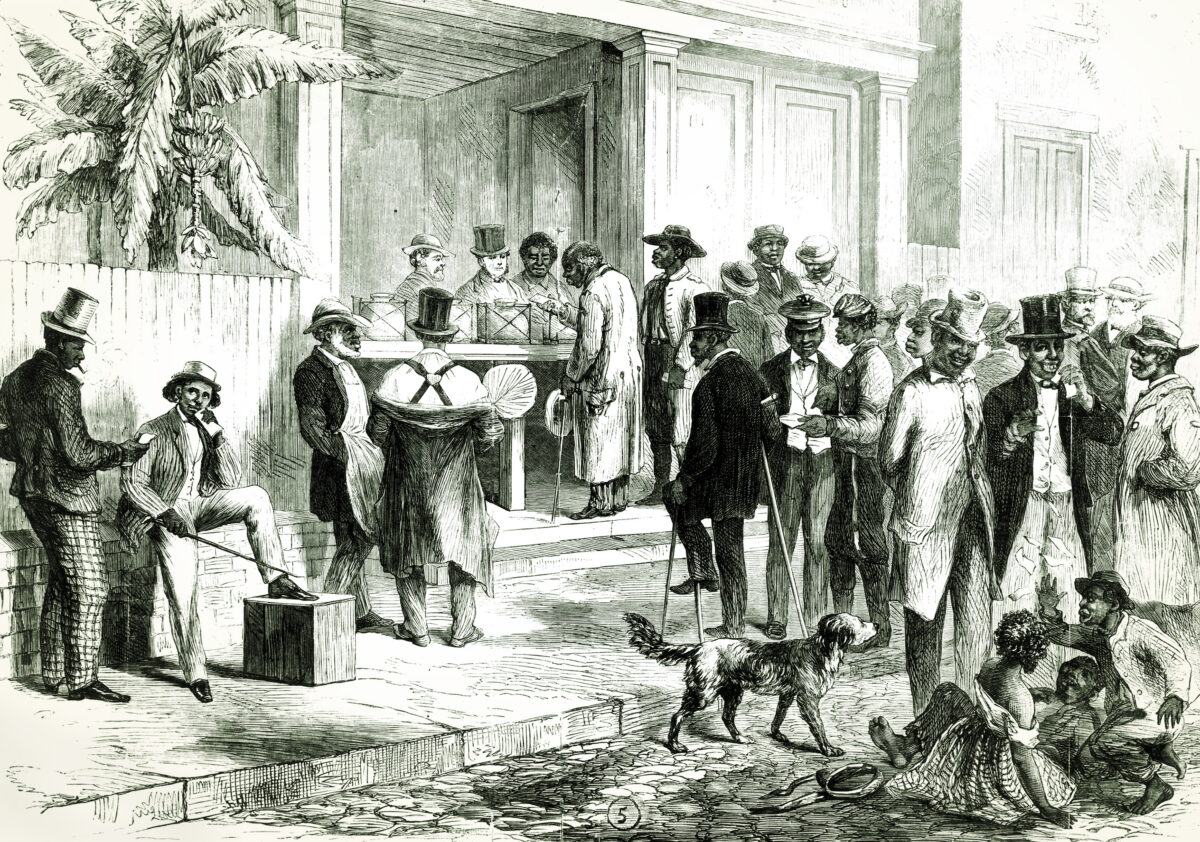

The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 entirely upended society in the American South, enfranchising Black men across the states of the former Confederacy and placing those states (except Tennessee) under the authority of the U.S. military. The acts created five military districts in the South, requiring new state constitutions to be drafted and the 14th Amendment ratified. While Black Southerners rejoiced at their citizenship status and set about exercising their newly won rights, federal occupation and Black suffrage was widely opposed by the region’s White population. Seeing Blacks casting ballots, negotiating labor contracts, and bearing arms panicked many former slaveowners. But even while residents branded federal occupation as “bayonet rule,” they were quick to seek U.S. troop intervention when feeling threatened by freedmen engaging in politics.

In 1867, Whites in St. Landry Parish, La., were rattled by the emergence of a well-regulated Black militia, which engaged in public drills, marches, assorted military pageantry and, perhaps most important, guarded Republican meetings from local belligerents (the Ku Klux Klan, etc.) and safely escorted Republican voters to the polls for elections. No doubt, St. Landry’s White citizens wouldn’t have resisted a return to the antebellum status quo, with Black Southerners essentially returned to a state of bondage—something they believed was unattainable as long as a Black militia remained mobilized.

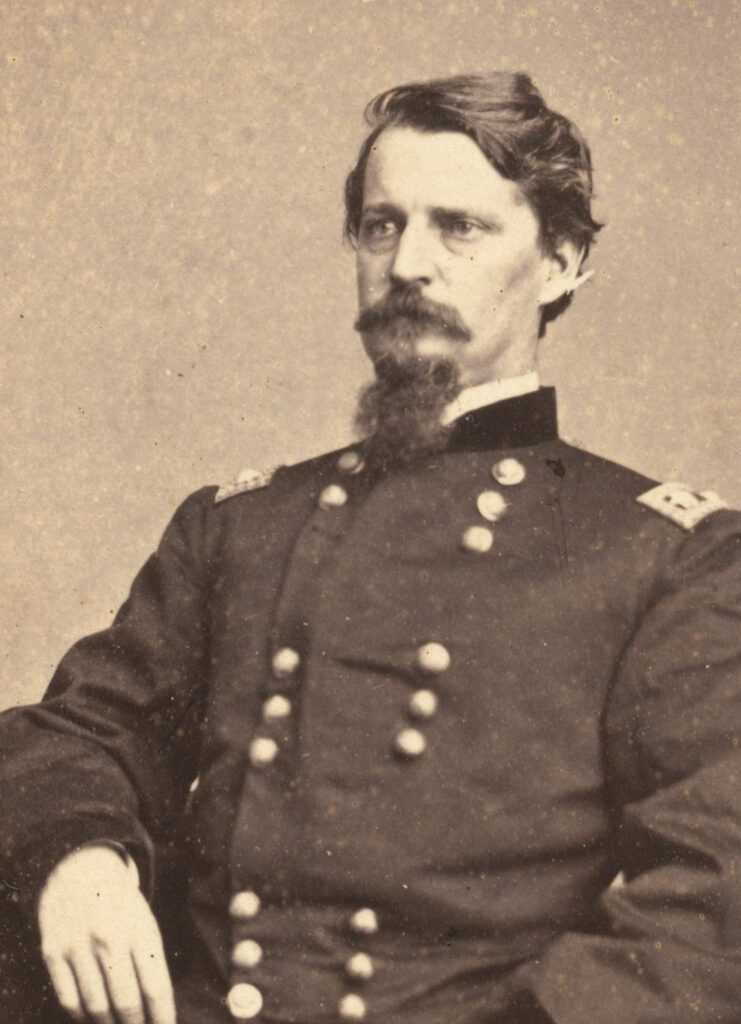

Serving as commander of the Fifth Military District, which consisted of Louisiana and Texas, was Civil War hero Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock. In December 1867, planters in St. Landry petitioned Hancock to send them an entire company of U.S. Cavalry “under the command of a prudent and discreet officer.” White Democrats across Louisiana railed against federal occupation in newspapers and in public speeches, but they nonetheless fully recognized that most U.S. soldiers harbored only a tepid commitment to Reconstruction.

In their petition, the planters claimed they had been satisfied with their previous post commander, Captain William W. Webb. Men like Webb—and White officers in general—had reservations about occupying what they considered domestic soil populated by American citizens. Few were willing to involve themselves in strife between the parties, even when clashes would turn violent and deadly.

The petition below, signed by hundreds of local citizens, was just one of dozens sent to Hancock in the fall of 1867.

Parish of St. Landry, LA

Opelousas, December 27, 1867

Sir: The undersigned citizens…impressed with the importance and necessity of the pacific influence of a small organized military force in our midst, respectfully request the commanding General to station at this place, a Company of U.S. Cavalry, under the command of a prudent and discreet officer.

During the time that Capt. W.W. Webb of Co. E. 4th U.S. Cavalry, was stationed at Opelousas, there were no disturbances; quiet reigned everywhere, and the community felt a sense of perfect security. [He] was eminently qualified for his positions. His firmness, justice and discretion, to say nothing of his affable manners, and conciliatory deportment, rendered him generally acceptable, and gave him a commanding influence, which he used for the promotion of the general good. When, several weeks ago, Gen. [Joseph A.] Mower, then commanding, thought proper to remove Capt. Webb’s command…our citizens respectfully protested, in a written memorial, of which no notice seems, so far, to have been taken…

In point of numbers, this is the most important rural population in the State. This Parish alone has registered about five thousand voters; and there are probably one thousand more male adults, who could not, or were not permitted to register. This large population is sufficiently compact to admit of easy and rapid concentration. It is about equally divided between the two races, who, under the influence of artful demagogues and designing men, are daily placed in positions of more decided antagonism. The failure of the crops of the past year, and the great difficulty of engaging situations for the future, have rendered the colored population restless, dissatisfied and uneasy. They are taught to believe, by unscrupulous leaders, that great injustice is done to them, and that the whites are their enemies. They are becoming more idle and vagrant under these influences, and consequently less obedient to the law. Larceny is becoming epidemic among them….They are just now in that condition when a few incendiary leaders could excite them to deeds of violence and great outrage. This is what we wish to avoid; and we think we are not mistaken in the remedy we suggest.

Such is the general respect for the authority of the U.S. Government, particularly as administered by the able and patriotic Commander of the Fifth Military District, that the mere presence of a Company of U.S. Cavalry, under a proper officer, would impart a…feeling of security, and effectually prevent the outbreak of public disturbance. We beg leave to assure [you]…that it is not from a mere sense of personal fear, as to the result of such an outbreak…that we invoke the presence of the military arm of the Government; but it is because we think the general interests of the Parish, the State, and the nation, would…be materially injured by any collision between the races….

In forwarding the petition to Hancock, the local Freedmen’s Bureau agent, Oscar H. Violet, insisted there was no cause for alarm and that the “armed assemblages” of freedpeople were peaceable and used their arms to withstand coercion into unfair labor contracts. Violet acknowledged the validity of the Black militia but nevertheless urged Hancock to dispatch a cavalry unit without delay. He complied, and the troopers began disarming and demobilizing the militia after arriving.

In February 1868, this force, accompanied by Violet, disrupted a meeting of the Opelousas Republican Club, proclaiming it illegal and ordering the freedpeople in attendance to disarm. Chafing at “garrison duty,” the unit’s commander was vocal in opposition to armed meetings of freedpeople and ordered them to cease. Black Republicans could no longer carry their arms in public. The local Black militia had been so weakened, in fact, it prompted one of the most horrific massacres in U.S. history.

In September 1868, the beating of a local freedman’s school teacher by White assailants spiraled into a clash between Black militiamen and St. Landry citizens. Disarmed and demobilized, with no federal troops willing to come to their aid, the militiamen were simply outgunned. White extremists, some of whom even had signed the 1867 petition, combed the parish capturing or killing any freedperson unfortunate enough to cross their path.

In what was known as the Opelousas Massacre, 21 captured militiamen were marched to a mass grave in a nearby woods and killed by firing squad, spawning weeks of racial violence and the slaying of an estimated 200 freedmen. In many ways, the 1867 petition and demobilization of St. Landry’s Black militia had made that possible.

J. Jacob Calhoun is a UVa. Ph.D. candidate.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.