In 1984 four veterans swam, ran and biked from coast to coast to honor the fallen

I went to the dedication service of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in the cold November of 1982 and left with an inspiration. I envisioned a team of veterans in a triathlon crossing the United States from the Pacific to Washington D.C. and placing a baton at the base of the Wall in homage to the names imprinted on the shimmering black granite panels. I was confident that an accomplished team could do it in two weeks and resolved to recruit a group of national-class veteran triathletes.

Twice before, I had finished among the top 20 percent in the acclaimed Ironman Triathlon in Kona, Hawaii. I considered my success a demonstration of veterans’ pride and spirit. In the 1982 Ironman competition, I thought I was the lone veteran in the 900-competitor field until I encountered Marine Corps Maj. John Bates. He was tougher than sharkskin and undaunted from three combat wounds in Vietnam. Bates was the perfect recruit for my new plan and became a lifelong friend.

I had served with Military Assistance Command, Vietnam in the Central Highlands, as an adviser/linguist assigned to work with officers of South Vietnam’s 23rd Division during the communists’ 1972 Spring Offensive, also known as the Easter Offensive. I was at Kontum when the city was attacked by the North Vietnamese in mid-May 1972—a siege that lasted for weeks until the North Vietnamese withdrew in early June. Although a sergeant at the time, I received a meritorious designation of “acting captain” during my two months at Kontum to reflect the importance of the intelligence intercept and translation work I did with my Vietnamese intel counterparts.

Post-Vietnam, I focused my pent-up energy on advanced academics and long-distance running. Even though I already had an undergraduate degree from the University of Iowa, I obtained two more—in psychology and social work from Boise State University. I then completed graduate work at the University of Hawaii in 1977 with a double major in psychiatric and international social work, along with studies in advanced Vietnamese.

I directed a county mental health program for Indochinese refugees in 1978-79 and then served on the senior inpatient staff for psychiatric care at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, California, where I was working at the at the time of the veterans triathlon.

I nearly made the Olympic trials in the 26-mile marathon for the 1976 Games. I missed the U.S. standard for the trials by just 2 minutes. I won the Hawaiian AAU Marathon championship in 1976 and set the record for the Big Island Marathon in 1977 by running the race in 2 hours, 25 minutes, besting some Olympians. Also in 1977, I won the Hawaiian-Pacific 50-mile championship when I finished in 5½ hours, the best road time in the U.

My triathlon quest had a threefold purpose: remind Americans along the route of the gallantry and sacrifice displayed by more than a million service members in Vietnam to keep their memory alive; raise awareness of the searches and diplomatic efforts to account for more than 2,500 Americans listed as missing in action, and acknowledge and strengthen the bonds with the South Vietnamese refugees who fought alongside us.

My goal was to hold the veterans triathlon in summer 1984. Finding top-tier veteran triathletes proved a challenge. I wanted people who had not only the physical conditioning and endurance to undertake this grueling cross-nation event but also a passionate belief in the cause.

Eventually a core team crystallized—me and three others.

Ron Barker, my twin brother, of Boise, Idaho, was an Army specialist 5 who served in Japan for 17 months during the Vietnam War. He was a communications analyst who tracked Soviet activity. Ron finished his three-year tour as Spanish linguist assigned to Homestead Air Force Base in Florida, where he monitored Cuba. A triathlete and national-class distance runner, he won the Pacific military 1,500-meter event.

Fraser Langford, of Campbell, California, a U.S. Air Force sergeant, was stationed in England as a cryptologist 1964-67. His younger brother was an infantryman in Vietnam in 1967 and experienced heavy combat. Langford was a superb cyclist and Ironman triathlete.

Thieu Nguyen-phuc, of San Jose, California, was a South Vietnamese air force chopper pilot and solid athlete. He was shot down twice in Quang Ngai province in northern South Vietnam during the 1971-72 period, but fortunately wasn’t seriously injured. He continued his fight against communist forces during South Vietnam’s final hours in April 1975 and escaped capture by flying his helicopter to an American carrier in the South China Sea. In the U.S., he got a business degree and went into the furniture business.

Bates, my Marine friend, was invited to join the triathlon team; however, because of active-duty responsibilities, he could cycle with us only in his home state of Arkansas. He would be accompanied by Andy Bryant, a U.S. Army chopper pilot in Vietnam, all-around athlete and nephew of legendary University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant.

A “spark plug” on our team was 13-year-old Danny Nguyen, my stepson, who brought youthful curiosity and enthusiasm to our effort. At times he would ride his bike alongside the formal triathletes to offer moral support.

The route outline and event schedule started with 4-mile relay swim off Long Beach, California, a subsequent 10K run (6 miles) and bike ride through Los Angeles, followed by nearly two weeks of continuous cycling interspersed with daily running.

States traversed on the way to Washington, D.C., were California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee and Virginia. We locked ourselves into a 13-day period to reach the Wall. That would require us to cover an average of 270 miles daily. The swell of emotion kindled by this pact was exhilarating and contagious.

At any given time, one or two veterans would be cycling or running, another driving a Volkswagen van we had purchased and the fourth resting for his aerobic turn. A big MIA/POW sign dominated the back of the van, whose open doors were reminiscent of a chopper on an operation in Vietnam. We borrowed a recreational vehicle to accommodate a small support team that provided meals and served as a contact for local media. Pam McMahan, a nurse in Vietnam, traveled with us and helped with the driving and coordinating our activities, along with Frank Gonzalez, a Vietnam veteran who assisted with media coverage.

At the end of our usual long day, we pulled off the road and slept in either the RV or the Volkswagen van with the doors open.

At a large and stirring reception given by the Los Angeles Vietnamese community on June 19, the day before we began the triathlon, team member Thieu stated the sentiments of many: “I am running to show the American people that we will always remember the help they gave us and to remind them to honor their veterans who gave so much.” I shared with the hosts our thanks and thoughts in both languages.

Earlier, members of San Jose/Bay Area Vietnamese community had hosted a support event. They were also addressed and thanked in their language. Additionally, the team made an emotional address to the California National League of POW/MIA Families.

As a motivation and team readiness experience, Fraser ran the challenging Sacramento 50-mile race with a 2,000-foot elevation change, and I accomplished a very hilly and daunting California 50-mile championship.

The “DC Day” mission was launched on June 20. Our 4-mile relay swim in the direction of Catalina Island, a popular boating and tourist site, was refreshing despite the smell of gasoline in the water off Belmont Shores in Long Beach. The boat guidance and provision came from a generous Vietnam veteran, J.R. Edgecomb. Out of the ocean, the team immediately ran a 6-mile run. I then took to the bike on an adrenaline high, speeding through Los Angeles traffic to the coast and southward for a 72-mile leg.

After breaking free of the megalopolis, we headed into the mountains, aiming for Phoenix. A few days later, off the bikes and running a final 4 miles into the city in 110-degree heat, the team stopped at the Vietnam veterans center for support and a television shoot.

We then climbed the Rockies to Flagstaff before dropping into New Mexico. In one unforgettable gritty moment, Langford passed a semi at more than 40 mph on a downgrade. Everyone was engrossed with the aerobic action—and simultaneously very concerned. Had Langford crashed, he would have been gathered up, last rites administered, and on with the mission!

As we approached Albuquerque, a contingent of Vietnam veterans from the Laguna tribe suddenly appeared on the roadside waving the Stars and Stripes. They proudly held the flag as straight as the final plant on Iwo Jima in World War II. In Old Town Albuquerque, the team was joined in an elaborate and stirring ceremony with the community’s veterans. Supportive Vietnamese residents invited us to a gratis restaurant meal. The inspirational energy that accompanied us as we cycled out of the city that night was incredible!

Humidity and increased temperatures weighed on the team as we traversed the flat stretches of Northwest Texas. The local populace was curious and very friendly. Some teenagers at a water stop were amazed that none of the triathlon team had ever smoked or tried substances to get high.

Generous truckers who were hauling produce to markets donated fresh food. Sometimes people spontaneously donated cash. This sensitivity and generosity occurred throughout the journey. The team never made any solicitations for money.

Verging into Oklahoma, we set our sights on Oklahoma City and a meeting with Gov. George Nigh’s staff. En route, we encountered a marvelously patriotic lady, Elizabeth Roy, riding a donkey named Walter, on a journey to Oklahoma City that began eight months earlier in Southern California. She was raising funds and awareness for needy veterans.

At the Capitol, the governor’s staff greeted us and presented a proclamation. A Cherokee chief presented an eagle feather to Langford, who has Cherokee heritage. We offered a commemorative baton as I stated the team’s objectives. During public presentations, we had hand towels ready because our eyes stung from the saline of perspiration in the intense weather.

When we got to the Arkansas border, we were excited to see Bates and Bryant. Both men rode with the team through the entire Arkansas route. One of the peak experiences of our trip was meeting with Lt. Gov. Winston Bryant in Little Rock. Addressing the assembled veterans and community members, I spoke about the service and sacrifice of Americans and South Vietnamese and emphasized the importance of accounting for those still missing in Indochina. After a spirited jog downtown, the team was featured at an American Legion convention of several hundred members.

As the team reached the Tennessee border and crossed over the vast Mississippi River, we were filled with elation. We sensed that we could be victorious in reaching Washington on schedule. Cycling the freeway maze that night in Memphis was a challenge that required focus.

The following morning, as we proceeded to attack the lengthy distance of the Volunteer State, the Tennessee Highway Patrol—to everyone’s astonishment—instructed us to get off the freeway and travel on secondary roads. This increased our mileage load and the physical difficulty. Although the rural scenery was delightful, the team was committed to the July 4 arrival date in Washington. We had to cycle more hours, and late nights became the new standard. However, local sheriffs’ personnel were very friendly and understanding. As we cycled by some farms at night in pitch darkness, we received a huge wave of applause by gatherings of people we never saw. It was a moving experience.

In Virginia, we ran into a similar speed bump. The state Highways Department required the team to adhere to secondary roads. Night cycling became quite treacherous, with rain on undulating surfaces through winding, limestone-rich country roads. But our spirit of brotherhood and camaraderie prevailed. The challenge now had the added dimension of a “crusade.” In one bike leg a team member was too physically and emotionally spent to ride. I took his place in the blackness of the night.

The following day brought the team close to Lynchburg, a major Civil War battleground. As we neared the city, the road seemed to rise in multiple terraces. Each rider attacked this challenge with ferocity, confronting rise after rise. On the final stretch into the city, a few were convulsing and had to be lifted off their bikes.

We got some relief on the stretch of road leading to Richmond. Entering the city, we felt like a jubilant band of conquering Union soldiers. We met with Gov. Charles Rob, a Marine Corps captain in Vietnam, and presented him with a plaque and ceremonial baton—a special moment for the team. In the final phase of our Virginia crossing, we cycled to the entrance of Marine Corps Base Quantico, about 35 miles south of Washington. Like victors standing exultantly before the Arc of Triumph after winning the Tour de France, we raised our bikes high in a team shout in front of the white statue replica of the one near Arlington National Cemetery that depicts the flag raising on Iwo Jima.

The next day, July 4, the team entered the District of Columbia. After a mere two hours rest, we ran 4 miles to stand in reverence during the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Afterward, everyone on the team was propelled by pure euphoric spirit on our remaining 7 miles to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Pacing down Constitution Avenue the final mile felt like floating on air!

A sense prevailed that our final footsteps were a recapitulation of history—like the solo runner of Ancient Greece approaching from the plains of Marathon proclaiming, “Athens is saved,” before drawing his last breath. There was a difference, though. Four living veterans were engaging the resonant spirits of the unliving.

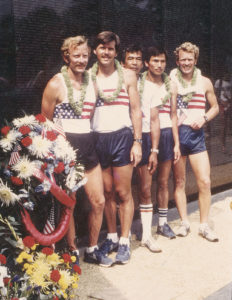

The team strode directly to the apex of the Wall. A gathering of veterans and Vietnamese Americans waited there. We stood at a spot festooned with beautiful wreaths of red, white and blue flowers, as well as those of brilliant yellow and red, the colors of the South Vietnamese flag.

I thanked all for their faithful support and offered a few remarks. I focused on the mutual struggle and sacrifice of Americans and South Vietnamese in resistance to the tyranny of communism. The assembly was addressed in both languages. I said we have never abandoned our commitment to service in defense of freedom.

The gathering could see some of the physical toll from our team’s cross-nation odyssey that doubters said was not possible in the 13-day period we committed to.

A former South Vietnamese general expressed his gratitude. A Georgetown University professor who was a refugee gave his blessing. An elderly Vietnamese woman stood tenaciously holding the flags of two nations. A nearby Vietnam veteran’s wife guided her tentative husband closer to the Wall. His gaze lifted to see he was surrounded by friends.

In retrospection over the years since then, I have come to see our team’s experiences and achievement as validation of my beliefs as a veteran: Causes of dignity and principle may require everything you have. V

Jim Barker served in Vietnam July 1969-July 1972. He was on the senior inpatient staff at the VA Medical Center in Palo Alto, California 1979-2006. He also taught Vietnamese part time at Mission College in Santa Clara 1997-2004. Barker lives in Keaau, Hawaii.

This article appeared in the August 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: