Colonel Neel Kearby was among the top scorers in the Pacific when he pushed his luck too far while chasing Eddie Rickenbacker’s record.

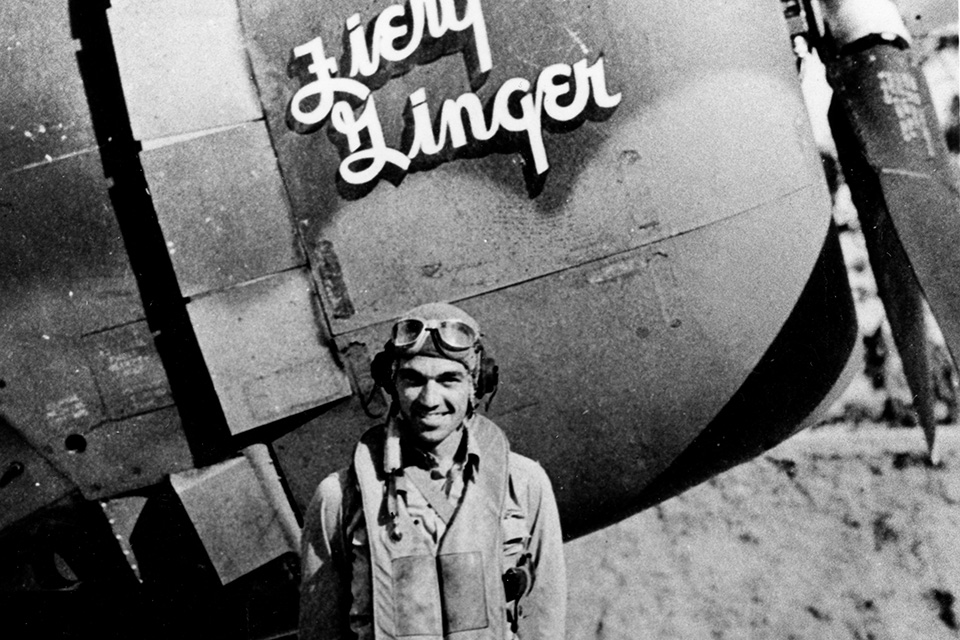

Neel Kearby achieved some remarkable things before his lamentably short life ended over New Guinea in March 1944. He became a U.S. Army Air Corps pilot in September 1940, and in 1941 was commanding officer of the 14th Pursuit Squadron in the Panama Canal Zone. By October 1942, he was a major in command of the 348th Fighter Group. Within the next 18 months he would take charge of the Fifth Air Force’s V Fighter Command, be recognized as the top P-47 Thunderbolt pilot in the Pacific and earn the Medal of Honor.

Almost from the first time he took to a fighter cockpit, Kearby developed a reputation as a formidable dogfighter. His fame spread to the point that other young pilots sought him out to help sharpen their skills. One pilot pestered Kearby with such insistence that a series of mock combats was arranged for his benefit. The two men took off in Seversky P-35s—the sire of the Republic P-47 that would carry Kearby to glory. The practice encounter started on equal terms, but Kearby quickly gained the advantage behind his opponent. With every skill at his command the young pilot tried to evade his attacker, only to look around and find Kearby close enough to be seen calmly lighting a cigarette behind his windscreen!

The Seversky Company became Republic Aircraft and the P-47 started to come off the assembly lines in 1942. One of the first units to convert to the new type was the 348th Fighter Group, which was activated at the end of September. Major Kearby took charge of the unit in October 1942, and was quickly impressed by the 7-ton giant of a fighter.

The 348th was assigned to the Fifth Air Force in early 1943. Lieutenant General George Kenney, the dynamic leader of the Fifth in New Guinea, was determined to take the initiative in the Southwest Pacific. Although Allied military planners had decided to give priority to the European theater, Kenney prevailed on American decision-makers to send him enough equipment and manpower to mount offensive operations. The 348th was one of the concessions sent to his command.

There was a general consensus against the P-47 in the Pacific. Most commanders believed it was too heavy for combat with highly maneuverable Japanese fighters, and its limited range made it undesirable for the long-distance operations typical in the area. Kenney, however, was interested in building up his forces and knew that any equipment could be used to maximum capability. When he heard the 348th and its P-47s would arrive at Port Moresby sometime in June, he was reportedly so pleased that he said he would meet Kearby with a brass band. According to Kenney, when they finally did meet the first thing Lt. Col. Kearby asked was where he could find the nearest Japanese. The general promised imminent action and commented to his subordinates that the fighter leader looked like money in the bank.

Kearby studied the tactical situation while he honed the flying and organizational skills of his personnel to prepare them for combat. With effective support from an eager Fifth Air Force command, the group’s P-47s were ready for action by the beginning of August.

Kearby’s enthusiasm for the P-47 irritated some P-38 Lightning devotees, who heatedly challenged him to a mock combat. Kearby accepted the challenge, and on August 1 met 16-victory P-38 ace Dick Bong in the skies over Port Moresby. Witnesses judged the contest according to their aircraft or pilot preference, but objective opinion seems to rate the duel a draw. Bong’s flight log simply states that he met Kearby in a mock combat that lasted about 35 minutes.

The 348th’s tactics centered on the P-47’s high-altitude performance. Kearby stressed the ability of the large fighter to strike quickly from the heights to shred unwary Japanese formations with its eight .50-caliber guns. Flights were arranged to give the Americans every advantage in finding the enemy below before the Japanese were aware of their presence.

The 348th drew first blood during a transport escort mission to Marilinan on August 16. After the transports landed, about a dozen Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscars” attacked. With two bursts of fire, Lieutenant Thomas Barber sent one down into a wild spin. Captain Max Wiecks took on another Oscar in a head-on pass, and the enemy fighter fell in flames after the two planes narrowly avoided a collision. With the 348th’s first two confirmed victories for no American losses, the P-47 was off to a good start in the theater.

Kearby himself would account for the next group victories. In his combat report for the September 4 bomber-interception mission along the Huon Peninsula, he recounted: “I was leading the fifth flight and when at 25,000 feet I observed one bomber with a fighter on each wing at a low altitude. After observing them for two or three minutes I decided to investigate. I hesitated because I hated to lose that precious altitude, and from the radio conversation there were flights all around.”

When nobody else went after the Japanese bomber, Kearby released his external tank and dived on the enemy. “When at about 3000 feet I saw the red balls on the wings of the Oscars and [Mitsubishi G4M] Betty. I closed to 1500 feet and opened fire. I led the Betty and Oscar about one-half radii, hoping to get both of them, but was most interested in the Betty. Tracers were seen passing around the Oscar, and then, closing in, the Betty burst into flame.”

Kearby’s wingman Lieutenant George Orr, whose guns had jammed while he pursued the second Oscar, saw the enemy fighter that Kearby attacked dive into the water. It was a spectacular victory in which the fighter leader managed to attack two targets simultaneously for his first two kills.

Ten days later Kearby was leading eight P-47s on a top cover mission for transports bound for Malahang when he received a radar report of bogies in the area. He shot down a Mitsubishi Ki-46 “Dinah” twin-engine reconnaissance plane for his third confirmed victory. It would be the last tally for him until his most celebrated combat.

During this period of the New Guinea campaign, Lockheed’s P-38 was establishing its reputation as the premier offensive fighter in the area. Its range and dominion over Japanese aircraft made it the weapon of choice for offensive operations, and it forced other Fifth Air Force fighters to take a back seat. Kearby was determined to change that situation, so he pressed every opportunity to place his P-47s in the center of battle.

more pacific aces

One of the ways he sought to take advantage of the Thunderbolt’s strengths was to commit it to the free fighter sweep. His first opportunity came on October 11, when he led four fighters over the teeming Japanese base at Wewak. Kearby’s flight arrived over the area at 26,000 feet around 10:30 a.m. Forty-five minutes later he sighted a single enemy fighter (he reported it as a Zero, but it was almost certainly an Oscar) 1,500 feet below, and immediately attacked. Opening fire from about 200 yards, Kearby saw the Japanese fighter burst into flames. Then he zoomed back to 26,000 feet and searched for new prey. After 10 minutes, he saw about 36 Oscars and Kawasaki Ki-61 “Tonys” covering a dozen unidentified bombers along the coast at 10,000 feet. He led the flight down in a fast dive onto the tail of the enemy force.

Captain John Moore was flying on Kearby’s wing and had seen the first Oscar go down in the water. Moore, the 341st Squadron operations officer, was glad to have the opportunity to go along on a promising mission as his commander’s wingman. Within a few seconds, he witnessed Kearby shoot down another Oscar and Captain Bill “Dinghy” Dunham, one of Kearby’s close comrades from his days in Panama, flame a Tony that was trying to close on the flight leader’s tail. With only a slight rudder adjustment, Kearby slipped in behind a third Oscar that took no evasive action before it also went down in flames. Yet another Oscar was above and quickly came into his sights, going down in full view of Dunham and Moore.

With the four P-47s’ fuel running low, Moore remembered in his after-action report hearing Dunham and Major Raymond Gallagher call over the radio that they were turning for home. Moore also noted that he spotted Kearby in the midst of a flock of Japanese fighters. Diving to his leader’s aid, Moore opened fire on a Tony and saw the fighter falling in flames until it passed from view under his wing, to become a probable victory.

Then reality set in for Moore. He saw another Tony fall to Kearby’s fire before three enemy fighters came down on his own tail. The Tonys followed Moore in a dive until Kearby came to his rescue and shot down the third fighter in the string. Moore was happy to confirm Kearby’s sixth kill for the day. The two Americans circled the area long enough to count the plumes of smoke emerging from the green foliage and blue sea. Kearby would be awarded the Medal of Honor in January 1944 for his bravery on that mission.

On October 16, 1943, the 348th escorted a group of B-25s to Alexishafen and downed a dozen enemy interceptors for no American losses. At the same time, Kearby led a fighter sweep over Wewak and shot down an Oscar for his 10th confirmed kill.

Kearby led another P-47 sweep over the Wewak area on the 19th, during which a group of six Mitsubishi F1M2 “Pete” floatplanes was spotted taking off from an island. The little Japanese biplanes were in the worst possible situation, with white takeoff wakes still trailing behind when the Americans descended on them. All four P-47s destroyed one Pete each in the first pass, then turned for a second pass. Kearby sent another floatplane into the sea with a 90-degree deflection shot, while another P-47 pilot claimed the sixth Japanese aircraft.

Kearby now had 12 victories to his credit, all scored within six weeks. By this point in the war only two pilots in the Pacific theater, both flying P-38s, were ahead of him in number of victories: Dick Bong with 15 downed over nine months and Tommy McGuire with 13 in 10 weeks (though he had been shot down on October 17 after claiming three kills and would spend the next six weeks in a hospital). At that time Kearby was the fastest scoring American pilot of the war.

On November 24, Kearby, by then a full colonel, became the leader of V Fighter Command, boosting his influence but also putting the brakes on his meteoric aerial scoring. At least he was now in a position to hasten the conversion of fighter units to the P-47. The worldwide shortage of P-38s became acute at the end of 1943, especially in the Southwest Pacific, which was a low priority on the supply chain and had just lost a number of Lightnings during the Rabaul campaign.

By January 1944, about half the fighters in V Fighter Command were P-47s, annoying many former P-38 pilots, who missed the range and other advantages of the Lockheed twin. Some pilots became accustomed to the P-47 and learned to appreciate its merits, but most continued to dislike the “Jug” and blamed Kearby for its proliferation.

By any measure, Kearby hated his job as head of the command. He still managed to claim seven victories before he took command of the 309th Bomb Wing on February 26. This new assignment at least gave him more opportunities to fly missions with his beloved 348th Fighter Group. Meanwhile, Bong had raised the scoring bar in November 1943, becoming the first U.S. Army pilot to attain his 20th victory. Now the goal was to surpass Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s legendary World War I record of 26 air victories.

Bong and Lt. Col. Thomas Lynch had been taken out of combat at the end of 1943, but had returned to the theater during the first months of 1944 to fly free sweeps together while attached to V Fighter Command. Bong was still the ranking ace, with 21 victories, while Lynch returned with 16.

Kearby, now with 19 victories, kept the contest tight when he led yet another four-plane P-47 sweep over Wewak on January 9. Attacking a group of 18 Tonys head-on directly over the harbor, he sent one down with smoke trailing behind. He caught another a few miles out to sea, and watched it fall in flames into the water for his 21st victory.

The race of aces heated up in March, when Bong scored his 22nd victory and Lynch his 20th. Kearby felt increased pressure to win the competition, but there was a dark side to the race to beat Rickenbacker. Marine Corps Captain Joe Foss had equaled the record as early as January 1943, but he was shot down and nearly killed in the process. A fellow Marine, Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, was also shot down and captured in his bid to break Rickenbacker’s record. Another Marine pilot, Captain Robert Hanson, was killed just as he reached the 25-victory mark. Lynch would be killed on March 8 while chasing the record with Bong. Whether they realized it or not, all the aces were tossing prudence to the wind for the honor of becoming the first American to attain 27 victories.

On March 5, Kearby took off in the afternoon to fly a sweep over the Tadji area with his old comrade, Captain Dunham, and another 348th ace, Captain Sam Blair. The three P-47s left the newly won airfield at Saidor, just north of the Huon Gulf, at 4 o’clock and were in the combat area an hour later.

Kearby was the first to sight a Ki-61 Tony flying below about 500 feet over the airstrip at Dagua. Since the Americans were at an altitude of 23,000 feet, the enemy fighter was allowed to land safely. Height was critical, so Kearby kept his fighters in an advantageous position. Not more than five minutes later the Americans observed three Japanese bombers coming in from the sea at about 500 feet. From their high vantage point the Americans thought they were Mitsubishi G3M “Nell” twin-engine aircraft, but postwar review of Japanese records suggests they were in fact Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lilys,” which had arrived from the Hollandia area at about that time.

This time Kearby ordered tanks dropped and led the three P-47s down in a fast dive on the enemy. Captain Blair, on the right, watched as the Japanese planes circled the airstrip, almost certainly in preparation for landing. Blair saw Dunham attack the bomber at left, and it burst into flames and crashed.

When the range was down to about 200 yards, Blair concentrated his fire on the right-hand bomber. He flashed over the target at a very high speed, then looked back and saw it crash into the ground. In the same moment he also saw Dunham make an ineffective pass at the center target, which had escaped Kearby’s usually flawless aim.

Dunham broke to the left to come full around heading in the opposite direction. He could see that all three bombers had gone down in the jungle and that Kearby was clawing for altitude. Kearby had evidently made a complete circle to attack and destroy the third Japanese bomber, and was now flying much too low and slow to evade an Oscar that was closing into firing range. The Oscar pilot, probably from the nearby 77th Sentai, was apparently intent on exacting revenge for the loss of his three comrades. Dunham frantically dived in a head-on attack and watched his tracers hit the enemy fighter even as the Oscar sent a burst into Kearby’s cockpit and engine.

Meanwhile Blair had recovered to the right above the scene of the fight and saw Dunham climb after his attack on the Oscar. Four columns of smoke now marked the demise of the Japanese aircraft. Kearby was nowhere to be seen.

After searching the area, Dunham and Blair flew back to land at Saidor around 6:30. They tried to call Kearby several times during the flight back, in the vain hope that he was able to navigate his crippled fighter home. Dunham was so beside himself with grief that he had to be restrained from taking off on a search mission in the gathering dark. When no word was received from other stations into the night, it was obvious that the indomitable Kearby had to be listed as missing in action.

Neel Kearby fell into the cracks of history when he was officially listed as killed in action at war’s end. His tally of 22 confirmed victories was the highest for a P-47 pilot in the Pacific, and he was one of only two Thunderbolt pilots to receive the Medal of Honor in WWII. His body, found about 140 miles from Wewak, where he had parachuted into the jungle and subsequently died from his wounds, was recovered by a Royal Australian Air Force search team after the war and returned to his home state of Texas for a quiet funeral in 1949.

Dick Bong finally broke Rickenbacker’s record on April 12 when he claimed three Oscars over Hollandia. He became America’s ace of aces with 40 victories, but was killed while testing a Lockheed P-80 jet fighter on August 6, 1945.

One final note relates to the wreckage of the P-47 Kearby flew on his last mission. In 2001 the remaining pieces of tail and other recognizable parts were transported out of the crash site. Those artifacts were donated to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, in 2003, and can now be viewed next to a smartly decorated P-47D painted in Colonel Kearby’s colors.

John Stanaway is the author of Kearby’s Thunderbolts: The 348th Fighter Group in World War II and Mustang and Thunderbolt Aces of the Pacific and CBI, which are recommended for further reading.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe click here!