After unopposed landings early on August 7, 1942, the invasion of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands—america’s first offensive of World War II—soon devolved into a bitter six-month conflict on land, at sea and in the air.

Men of Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine (“Old Breed”) Division and the Army’s newly formed 23rd “Americal” Infantry Division, led by Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, struggled through thick jungle, coconut groves and fetid mangrove swamps to overcome stubborn Japanese resistance, while the U.S. and Japanese navies each lost 24 warships and thousands of men in six major engagements in the waters around the big island. Meanwhile, Marine Corps, Navy and New Zealand fighter pilots of Brig. Gen. Roy S. Geiger’s “Cactus Air Force” waged a desperate campaign to stop air attacks on the American positions and interdict incoming enemy troopships. Until the end of November, the campaign’s outcome hung in the balance.

Saturday, November 7, began quietly for the pilots at Henderson Field, until a report came in that a Japanese cruiser and 10 destroyers had been spotted in the New Georgia Sound (known as “The Slot”), about 100 miles north of Guadalcanal. That afternoon, seven dive bombers and three torpedo bombers took off to attack the enemy force. They were escorted by stubby Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats of Marine fighter squadron VMF-121, led by lanky, handsome Captain Joseph J. Foss. A skilled pilot and marksman with an indomitable spirit, he had been on Guadalcanal for less than a month but had already shot down 14 Japanese airplanes in 13 days.

While the American bombers hit the Japanese cruiser twice and damaged a destroyer, “Foss’ Flying Circus” tangled with the covering force of Nakajima A6M2-N and Mitsubishi F1M2 floatplanes. In a wild dogfight, Foss claimed three enemy planes, but his Wildcat was crippled when the observer in his last victim shot up his engine. He tried to head for home, but was forced to ditch near the island of Malaita.

When the Wildcat hit the sea, the impact slammed the canopy shut. Struggling desperately with the latch as water rose to his chin, Foss was finally able to pop it and rise to the surface, buoyed by his parachute pack and Mae West lifejacket. He started swimming toward Malaita, two miles distant. Sharks circled him and darkness fell. “I did more praying that afternoon out there than I ever did in my life,” he recalled. When the sharks came closer, he tore open a pouch of chlorine powder and sprinkled it into the water to repel them.

After floundering for several hours, Foss was rescued by Malaita natives and a sawmill owner in dugout canoes. They conveyed him to the island, where local missionaries warmly welcomed him. Most of them had fled from other islands invaded by Japanese troops.

The next morning, after a Wildcat pilot flew over and saw the parachute Foss had stretched out to dry, a Consolidated PBY Catalina set down in a little bayou near the mission. Exchanging hurried but fond farewells with his hosts, Foss jumped into a canoe and was rowed out to the flying boat. The PBY carried him back to Henderson Field, where he went straight to the fighter readiness tent for a “grand reunion” with his squadron.

Joseph Jacob Foss was born on April 17, 1915, on a farm near Sioux Falls, S.D., where his family struggled to wrestle a livelihood out of the arid land. Life was hard, and it worsened when Joe’s father was killed in a car accident in 1933. The sturdy, good-natured youngster worked a number of jobs to help support his family. When droughts destroyed the crops in the 1935 and 1936 growing seasons, he provided most of the family’s income.

In his teenage years, Joe enjoyed hunting and fishing, and proved an expert marksman. He got his first look at airplanes in 1932, when Marine Corps pilots staged an airshow at a local fair. Fascinated, he paid five hard-earned dollars for a plane ride three years later, and took his first flying lesson in 1937. After high school, meanwhile, he attended Sioux Falls College and Augustana College for a year each before entering the University of South Dakota. By the time he graduated with a degree in business administration in 1940, he had logged 100 flying hours and gained a private pilot’s license.

Foss enlisted in the Marine Corps aviation program that year, was commissioned a second lieutenant and earned his wings in March 1941. Because he was such a skilled pilot, he was kept as a flight instructor at the naval air station in Pensacola, Fla., for a year. He was the officer of the day there on the fateful December 7, 1941. Foss applied for combat duty, first with the ill-fated Marine glider program, and then with a photographic squadron at NAS San Diego, the only slot available. He struggled through the photographic curriculum and described it as “one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.”

The Marine aviator dreamed of becoming a fighter pilot, though he was told that at the age of 27 he was too old. But he was determined. At North Island, he wangled his way into the Aircraft Carrier Training Group, being accepted because he was willing to do “all the dirty work,” such as sweeping the hangar and taking charge of burial details. Promoted to first lieutenant in April 1942, Foss managed to skirt red tape and get hold of a Wildcat. During a six-week period, he logged 156 flight hours in his off-duty time and learned all he could about fighter tactics and gunnery. His hard work paid off, and he was promoted to captain that August.

Foss was delighted when he was ordered to ship out to the Southwest Pacific as executive officer of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing’s VMF-121, led by Major Leonard K. “Duke” Davis. After catapulting off the deck of the new escort carrier Copahee on October 9, 1942, he and his squadron landed at Henderson Field, the muddy and much-strafed Guadalcanal “cow pasture.” The Cactus Air Force there had grown from an original complement of 19 Wildcats and 12 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers. Most of the pilots were young and inexperienced.

Foss had logged 1,400 hours’ flight time and established himself as an accomplished aerial marksman. Eager for action, he downed his first enemy aircraft, a Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero, on October 13, four days after his arrival. But it was a close call that taught him much. During an enemy bombing raid, a Zero came out of nowhere, overshot Foss’ Wildcat and flew into his sights. He instinctively pressed his trigger button, and the Zero exploded. Having failed to switch on his radio, Foss was wondering where his wingmen were when three more Zeros closed in from behind and shot up his fighter. After barely managing to make a dead-stick landing at Henderson Field, the chastened pilot told his crew chief, “That was close.” At the debriefing, Foss did not have to be told what he had done wrong. “You can call me Swivel-Neck Joe from now on,” he assured his comrades with a grin.

He also borrowed the tactics of his friend, rugged 33-year-old Colonel Harold W. Bauer, a Kansas-born Naval Academy graduate. Another popular “old man” fighter pilot, and widely regarded as the finest flier in the Marine Corps, Bauer had downed four Japanese fighters on October 3. His simple philosophy was to get so close to the enemy that he could not miss.

The Japanese raiders gave strategic Henderson Field no letup. Fourteen Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bombers and seven Zeros headed in on October 18, but 15 Wildcats from VMF-121 and VMF-122 had received ample early warning. They shot down one Zero in exchange for two American planes, whose pilots were recovered. When the bombers arrived, three were soon plummeting to their destruction, one at Foss’ hands. His machine-gun fire tore off one of the wings, and the bomber spun into the water off Tulagi, where three survivors of its seven-man crew were captured.

On October 23, when the Japanese launched a three-pronged assault on Guadalcanal, a welcoming committee of 24 Marine and Navy Wildcats was waiting. Foss counted 16 enemy bombers and 25 fighters as he led his men into action. As they rose to meet the threat, he spotted a Wildcat pursuing a Zero, with another Japanese fighter on its tail. Foss dived and fired at the menacing Zero. As it disintegrated, its propeller flew off and the pilot was thrown from his seat. Foss had to maneuver wildly to avoid flying into the pieces.

He downed another Zero, but his Wildcat was so riddled with bullets that he had to land and find another one, taking his pilots down with him to refuel and rearm. They then roared off from Henderson to close with the dozens of Zeros leading another approaching bomber formation. Foss destroyed two more enemy aircraft and then headed back to the field. He was just one plane shy of a kill for every day he had spent on the island.

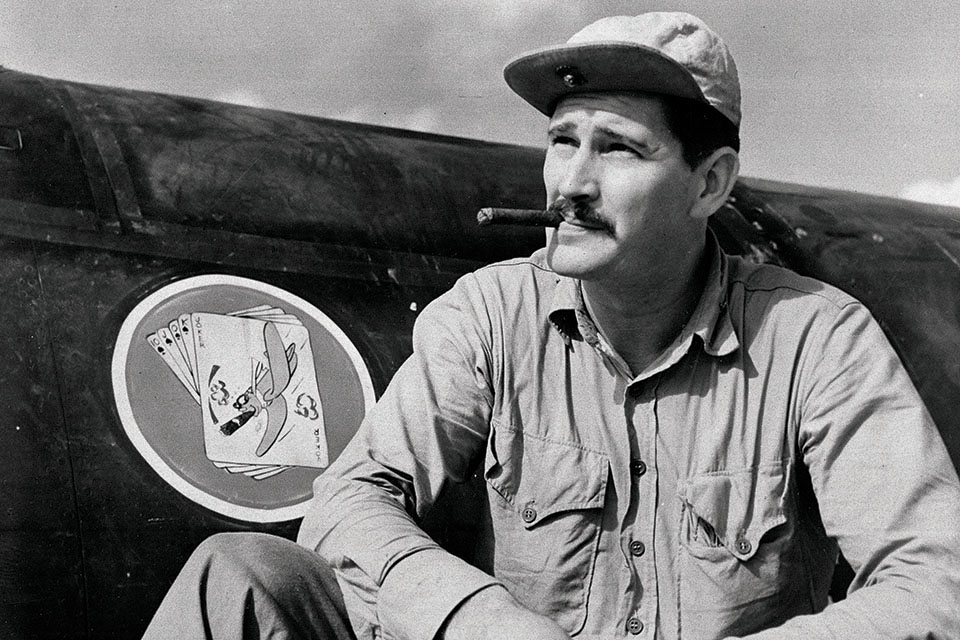

Foss flew with a cigar stub clamped between his teeth, establishing a reputation as a “barroom brawler” type of fighter pilot. He had become an ace in just five days, was shot up twice, suffered a head wound and, like many others on Guadalcanal, would be hampered by recurring bouts of malaria. But nothing would stop him.

Foss had become a legendary member of the Cactus Air Force, which served valiantly in support of the Marines and GIs during the six-month Guadalcanal struggle. Nearly 30 of the Cactus fliers became aces, and six were awarded the Medal of Honor.

Life at Henderson Field was a struggle for survival. It was shelled by Japanese ships, bombed almost daily and often turned into a quagmire by heavy rains. While Marine engineers and Navy construction battalions patched the field and hacked another airstrip in the jungle, the ground crews toiled feverishly to arm and refuel planes so that the overworked, underfed pilots could meet each enemy assault. Supplies were scarce and communications poor.

The value of teamwork was one of the first things Foss learned on Guadalcanal. “Whatever you do in life, you’ll succeed if you work as a team,” he wrote in the foreword to Barrett Tillman’s aviation Medal of Honor history, Above and Beyond. “We were outnumbered and outgunned, short of just about everything. What we had going for us was great leadership….We had genuine heroes….At ‘Cactus,’ we were simply doing what was expected of us, whether it was flying airplanes, keeping them flying, cooking Japanese rice or manning a Browning machine gun up on the ridge….I learned pretty quick that combat is a dangerous occupation. There’s no way to make war safe so the thing to do is make it dangerous for the other side….Whatever you thought of the Japanese after Pearl Harbor, you didn’t take them for granted.”

On November 9, two days after Foss’ return from Malaita, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey pinned the Distinguished Flying Cross on him and two other pilots. Foss was nominated for the Navy Cross, but the recommendation was not pursued because recordkeeping was poor, and there were too few medals on hand.

Four days later, Foss and his flight accompanied SBDs against fleeing Japanese warships that had severely damaged the heavy cruiser San Francisco and sunk six other vessels in the great naval battles of November 12-15. While strafing, Foss flew so close to the crippled battleship Hiei that he thumbed his nose at the white-uniformed officers lining its bridge. The American planes finished off Hiei.

During the action, Foss’ friend and leader, Colonel Bauer, claimed a Zero and was then shot down himself. Foss saw him swim clear of his sinking Wildcat and wave up at him, and he was confident they would share a cold beer back at Henderson that night. Foss and Major Joe Renner flew a Grumman J2F Duck to where their comrade had ditched, guided by the light of burning Japanese ships. But “Coach” Bauer was never seen again. He was eventually awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

The distressed Foss wrote to Bauer’s parents from Guadalcanal: “Marine Corps Aviation’s greatest loss in this war was that of your son, Joe. I am certain that wherever Joe is today, he is doing things the best way—the Bauer way.” Foss faced more disappointment: On the night of November 15, after downing his 23rd enemy plane, he awoke shaking violently from a severe malaria attack. He was evacuated to a hospital near Sydney, Australia, where he rested for six weeks.

Late in 1942, meanwhile, Japanese attacks tapered off, and the last “Tokyo Express” reinforcement convoy ran on November 30. Vandegrift’s Old Breed Division got a breather, and fewer enemy planes appeared over the Solomons, thanks to the Cactus Air Force, which had grown from the original 31 planes to more than 150.

After his recovery, Foss returned to Guadalcanal on New Year’s Day 1943. In mid-January, Japanese aerial attacks on Henderson intensified, and he was back in action. On January 15, he tore into a formation of Zeros off Vella Lavella and shot down three of them, becoming the first American fighter pilot to match the record of the famed Captain “Eddie” Rickenbacker, who claimed 26 German planes over France in 1918. Foss’ squadron went on to record 164 victories for the loss of 20 pilots.

Foss flew his last sortie on January 25, leading a mixed squadron of 12 Wildcats and Lockheed P-38 Lightnings to drive off a force of Japanese bombers. Four of the bombers went down, and the others were unable to reach their targets. The Marine Corps decided that Foss had seen enough action, so at the end of that month he was ordered back to the U.S.

Hailed as a national hero, Foss was feted everywhere he went. In great demand to help boost home-front morale, he toured from coast to coast, visiting munitions plants, promoting the sale of war bonds and lecturing on his experiences. But Foss was out of his element, calling the tour “the dancing bear act.” After President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented him with the Medal of Honor on May 18, 1943, for “aerial combat unsurpassed in this war,” his picture graced a Life magazine cover.

Returning to active duty and itching to get back in combat, Foss was stationed in Washington briefly and then was assigned to Marine Corps Air Station Santa Barbara, Calif., as a flight instructor. Promoted to major, he established VMF-115, nicknamed “Joe’s Jokers,” on July 17, 1943. The squadron was equipped with new gull-wing Vought F4U-1A Corsairs, and Foss and his men headed for the Pacific early in 1944. The Medal of Honor ace flew numerous combat missions, but aerial targets were scarce by then, and he had no opportunity to add to his score. After another bout of malaria, he returned home in September for treatment.

At the end of the war, Foss wanted to stay in the Marine Corps, but he fell victim to bureaucracy. With the backing of General Vandegrift, the new Corps commandant, he requested a regular commission, but was then told he was two weeks too old for it.

Discharged in 1945, he returned to Sioux Falls, where he and a friend organized a charter flight service. He helped establish the South Dakota Air National Guard, commanded its 175th Flight Squadron and, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, led a P-51 Mustang aerobatic team. He went on to hold the ranks of colonel and brigadier general in the Air Guard and the Air Force Reserve.

Foss became interested in politics, and won a seat in the South Dakota House of Representatives in 1949. The tireless ace served in the house until 1953, and then was elected governor of the state by a landslide in 1954 and re-elected in 1956. Foss made a bid for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1958, but was defeated by another distinguished flier, George S. McGovern, who had piloted a B-24 Liberator in WWII.

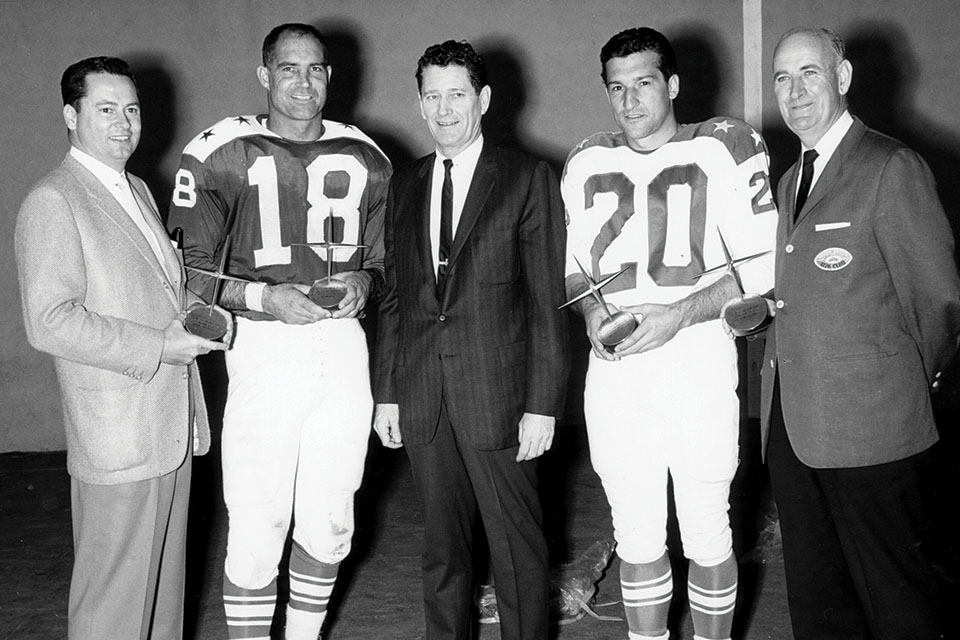

Foss became the first commissioner of the newly formed American Football League in 1959, and was responsible for a number of innovations in the sport. He held the post until the AFL merged with the National Football League in 1966. He produced two sports and outdoors television programs for several years, and was also active in the Air Force Association and the National Society of Crippled Children and Adults. As a longtime member of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, he came to know many prominent fliers, including Rickenbacker, Jimmy Doolittle and Charles Lindbergh. Ever modest about his own fame, Foss said, “For my money, the greatest fighter pilot I ever knew was Marion Carl [also of the Cactus Air Force]. Why he didn’t get the Medal of Honor is something I’ll never figure out.”

Foss served as an officer of KLM Airlines, president of the American Fighter Aces Association and was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1984. Appointed president of the National Rifle Association in 1986, he appeared on a Time magazine cover wearing a Stetson hat and holding a six-shooter.

Besides America’s highest decoration and the DFC, Joe Foss was awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart. He died on New Year’s Day 2003.

Longtime contributor Michael Hull is a career journalist and British Army veteran. Further reading: Joe Foss, Flying Marine: The Story of His Flying Circus, by Joe Foss and Walter Simmons; and Heroes of World War II, by Edward F. Murphy.

This feature appeared in the January 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!