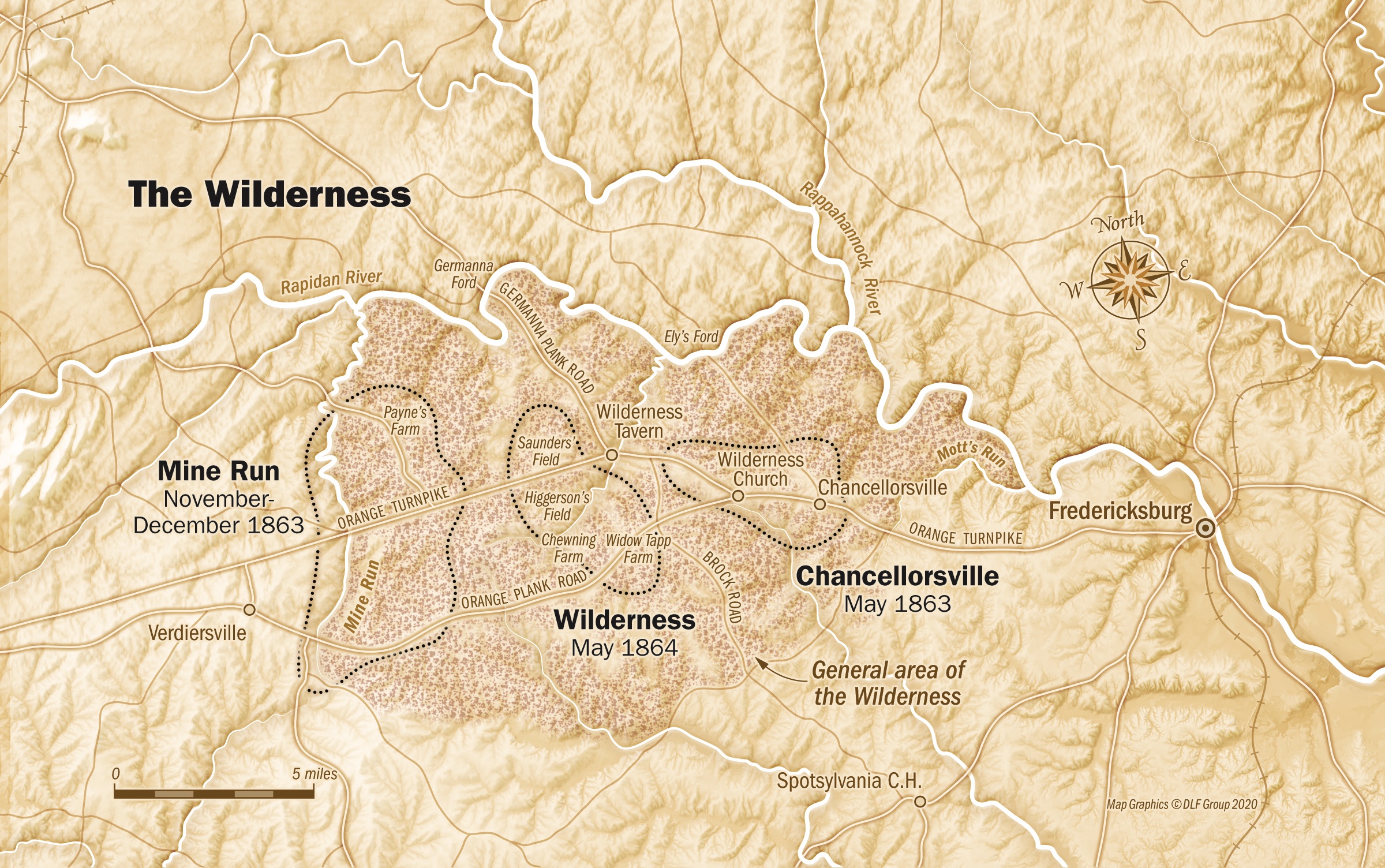

The Wilderness of Spotsylvania was a forested region of Virginia’s Orange and Spotsylvania counties just west of Fredericksburg, about halfway between Washington, D.C., and Richmond. It remains notorious as a grueling battleground. From the spring of 1863 to the spring of 1864, the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia conducted three campaigns, wholly or in part, within the Wilderness: Chancellorsville (April–May 1863); Mine Run (November–December 1863); and the Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864), the opening clash in Ulysses Grant’s Overland Campaign. The horrific casualties and miserable terrain at the Battle of the Wilderness left Union soldiers recounting the challenges of fighting in the region. Their lingering question, though, was why they had failed to defeat Robert E. Lee’s army. The attempt to answer this question led to the creation of a mythology that came to surround the Wilderness—a mythology that many later historians have uncritically parroted. In reality, as revealed in “The Battle of the Wilderness in Myth and Memory,” the Wilderness was a battlefield that indeed created very difficult combat conditions, but many of the claims of exceptionalism associated with it are unfounded, despite their wide-ranging influence in the annals of the Civil War.

It began with the name.

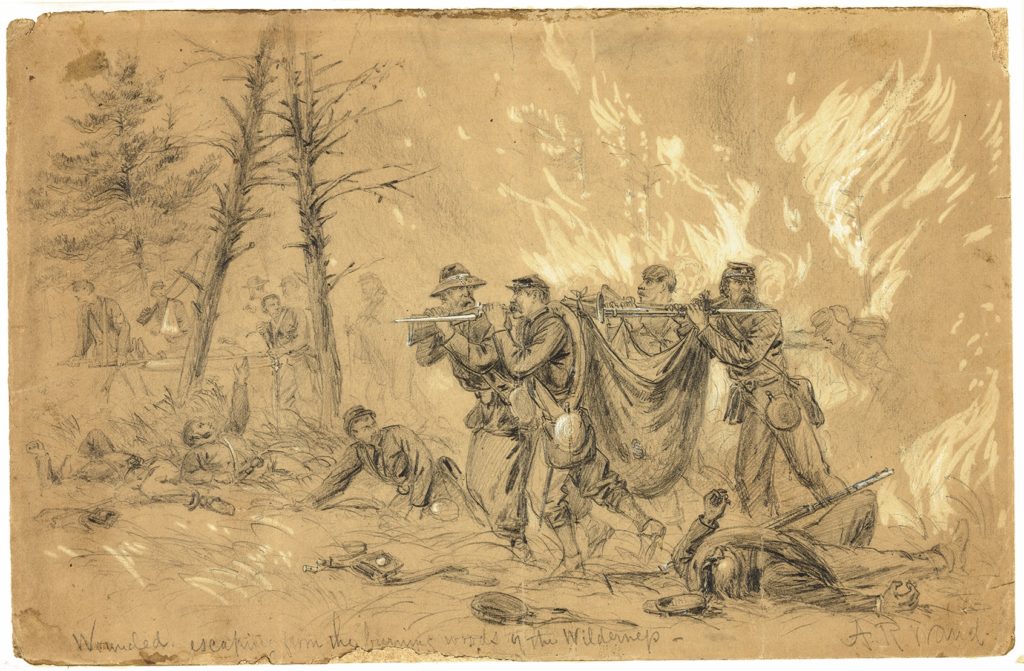

Unlike many battlefields, the Wilderness has an appellation that carries specific negative connotations, indicating a forest empty of man and beyond his control. The name also sets it apart as a distinct region. Many Union and Confederate soldiers who entered the Wilderness in the spring of 1863 had no inkling that they had stepped into a place marked by a special name and physical characteristics. By the time of the 1864 Overland Campaign, however, the men in both armies were calling it “the Wilderness” and attributing certain features to this forested region. Over time, and especially during the postwar years, descriptions of the Wilderness became images of a malevolent landscape. First in the contemporary accounts of the 1864 battle and later in postwar writings, the Wilderness became increasingly associated with death and destruction. The remains of the 1863 Chancellorsville battleground, the high casualties, the destruction of vegetation, and the corpses, skeletons, and graves that littered the Wilderness combined to cast the region as a place where the shadow of death lingered. It also became connected with the fires that ravaged the battlefield and engulfed the wounded. These images of death and destruction, fire and hell, formed important elements in the Wilderness mystique. The supernatural also found its way into the legend, as postwar writers portrayed the Wilderness as haunted or even as a spirit itself that could lash out and change the course of battle—and with it, the destiny of the nation.

While most Civil War engagements derived their names from a nearby town, landmark, or body of water, the Battle of the Wilderness took its appellation from a region. It is with this name—the Wilderness—that any investigation should commence, for it was not a neutral term. In order to understand a place bestowed with such an evocative name, it is necessary to investigate the term’s origin as well as the contemporary meaning it held for Civil War soldiers. Roderick Nash, in his trailblazing book Wilderness and the American Mind, argued, “although later extensions of its meaning obscured the word’s original precision, the initial image wilderness generally evokes is that of a forest primeval.” The term also “implied the absence of men, and the wilderness was conceived as a region where a person was likely to get into a disordered, confused, or ‘wild’ condition.” When soldiers encountered the Wilderness, they often remarked that the name fit perfectly. Moreover, they agreed with Nash’s definition and pointed to the lack of cultivation, the vast unbroken forest, and the absence of inhabitants as the region’s defining characteristics. “It may well be called the Wilderness,” explained Union Colonel Robert McAllister, “for there is not one acre of land in a hundred that is cleared.” Likewise, a Rhode Island infantryman remarked that “this place is called the Wilderness” and judged that “it is rightly named for [in] ten square miles there is not a dozen acres of cleared land.” In short, the Wilderness was a region full of trees, empty of men, and seemingly beyond human control.

Although the name was meaningful in itself, the Wilderness’ mystique was more than just a catchy label. Over time the region developed a reputation as a malevolent landscape, a process that culminated in the war’s aftermath. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, many, if not most, soldiers failed to recognize the Wilderness as a distinct place and merely commented on some of its features, such as dense woods and underbrush. Moreover, the feelings expressed toward the Wilderness were usually neutral. During the Mine Run Campaign that November–December, however, an increasing number of Union soldiers began to recognize the Wilderness as a special and seemingly hostile environment. They tended to focus on the vast forest as a perfect incarnation of a wild country. By early May 1864, soldiers in both blue and gray were calling the battleground the Wilderness and continued to marvel at how fittingly it was named. This pattern continued into the postwar years, when visitors and writers set the Wilderness apart as a strange and hostile environment.

The Chancellorsville Campaign was the first encounter the two armies had with the Wilderness, and the soldiers’ reactions were mixed. Many witnesses gave no indication they knew the name of the place or that there was anything special or distinct about the region. They might have noticed certain environmental characteristics such as thick woods, swampy areas, and vegetation, but there was no effort to make these local observations apply to the entire region. For many soldiers on both sides, the Wilderness at this point was just an undefined forest in which they happened to be fighting.

By the time of the Mine Run Campaign, an increasing number of Union soldiers showed an awareness that they were in a distinct region known as the Wilderness, a marked change from Chancellorsville. Examples of this recognition abound, often coupled with commentary on the density and breadth of the forest. A soldier from the 13th Massachusetts told the folks back home that the regiment was “now in the portion of Virginia known as the Wilderness, it being almost impenetrable, and extending for miles, in front, rear, and on both flanks.” Of special interest is the description offered by a soldier from the 65th New York. He reported, “we entered the Wilderness, and for six miles saw nothing but forests on either hand; dense, black, mysterious, the abode of hydras and goblins.” This last remark hints at the fearful images already developing in the minds of Union soldiers.

In contrast, Confederate soldiers during the Mine Run Campaign generally did not identify the Wilderness as a specific place, although they did comment on some of its salient features. For instance, Robert E. Lee did not name the region but did describe “the country in that vicinity” as “being almost an unbroken forest.” But there was nothing here to set the Wilderness apart in their minds, and certainly none implied that it was a particularly frightening place.

During the Overland Campaign, negative portrayals of the Wilderness by Union soldiers grew in frequency and intensity. A member of the 143rd Pennsylvania wrote home that he could hardly “give…any idea of the country through here” but encouraged his parents to “just think of…nothing but woods of scrub oak, stunted pines, and vines with here and there a small farm and a cleared field with ravines and hollows and a stream of water here and there.” Perhaps a Pennsylvania soldier best captured the prevailing sentiment, saying that the Wilderness’ name was “a word which expressed much of the toil and pain to any one who has experienced its brushy and swampy and somber realities.”

During this campaign, many Confederates showed a newfound awareness of the Wilderness, recognizing the woods as a distinct place for the first time. One Rebel remarked that they “fought in the woods of the Wilderness (a very continuously and densely wooded poverty stricken section in Spotsylvania Co. in which the Battle of Chancellorsville was fought).” One of the richest portrayals of the Wilderness was by Alexander Boteler, a member of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s staff. He agreed with his Union opponents that its name “fitly applies to the locality it designates, for a gloomier, wilder and more forbidding region can hardly be found this side of the Alleghanies [sic].” The stark contrast between these descriptions and those provided by Confederates at Chancellorsville and Mine Run suggest a sea change in their understanding of the Wilderness.

What would cause soldiers’ descriptions of the Wilderness to evolve over the course of the three campaigns? One possible explanation is the far from uniform vegetation. Some Union veterans argued that there was a core, or heart, of the Wilderness, where the forest was supposedly thicker than the woods around Chancellorsville or the woodlands stretching toward Mine Run.

It is also conceivable that the Union forces had simply developed an aversion to the Wilderness through experience. Repeated frustrations only compounded with each failure, leading men to view the forest south of the Rapidan as a place of misfortune. It seems likely, however, that if the armies had not met for a third time in the Wilderness in May 1864, then its name might have little meaning to modern historians.

Another possibility is that Union soldiers might have found the woods in the Wilderness more noteworthy. For example, when writing his memoir, Norton C. Shepard of the 146th New York felt obliged to clarify the different meanings “wilderness” had in the North and South. “In the North,” he explained, “a wilderness is a wood in a state of nature with great trees that have stood for ages, with other trees uprooted and fallen, with old logs lying prone upon the ground, with dry stubs and dead trees ready to fall at the first storm, so that in places it is almost impossible to travel.” To this primeval, Northern notion of wilderness, Shepard contrasted the Southern, manmade version. He found that “in the South…especially in Virginia, most of the land has been cleared off and cultivated,” and “after many years of cultivation it has become worn out and has been abandoned as useless.” In the place of the original forest “grows up…pine and scrub oak to become a wilderness,” with trees that “are usually about six inches in diameter with branches growing thick from the ground to the top.” Shepard’s explanation, then, suggests that Union soldiers were unaccustomed to seeing these sorts of wasted and abandoned areas in the North, while Southerners might have found them more familiar and thus less worthy of remark.

There is also the influence of newspapers. While the relationship is not clear, there is no question that journalists were identifying the Wilderness and describing its characteristics from early on. A Richmond newspaper, for instance, published a report after Chancellorsville that gave the region’s name and called it “a country of gravelly clay soil, and a black-jack growth, presenting in many places an almost impenetrable thicket.” Likewise, during the Mine Run Campaign, a correspondent for The New York Times labeled “the country hereabouts…one of the worst conceivable for field operations,” arguing that “it is truly named the ‘Wilderness,’ for a wilderness of small growth wood covers nine-tenths of the whole surface of the country.” Suffice it to say that newspapers had the potential to spread these perceptions of the Wilderness, if they needed spreading, and shape the soldiers’ attitudes toward the region.

The increasingly negative descriptions of the Wilderness actually gained strength in postwar memoirs and histories. One Confederate veteran noted, “what I have read—& more particularly from northern writers[—]raises a mistery [sic] or horror about the name of that part of Spottsylvania Co,” an observation that other postwar writings bear out. Hazard Stevens called the forest “dense, gloomy, and monotonous,” while another Union veteran, Thomas Hyde, portrayed the Wilderness as a “bushy, briery, labyrinth.”

Not only was the Wilderness a strange place but also, for some Federals, an enemy. Sartell Prentice portrayed nature as having refurbished the exploited land only to wreak vengeance on man when he returned in 1864: “Nature’s obstacles hindered and hurt the invading thousands in such way as history tells no like of in all its hundreds of years of memory.” Likewise, the historian of the 146th New York recalled the “sense of ominous dread which many of us found almost impossible to shake off” as the sounds of birds, insects, and hushed men combined, “seeming to forebode evil to those who had invaded this solitude.”

Postwar travel accounts continued to portray the Wilderness as a malevolent landscape. An article for Metropolitan Magazine published in 1907 tried to explain the feeling of traversing the Wilderness, where the “path is narrow, dense foliage meets overhead, and the traveler is completely hemmed in.” The “solitude is awesome, broken only by the disturbance of the dry leaves as the lizards and creeping things flee before approaching hoofbeats. It is boundless!” An 1879 narrative betrayed the anticipation one traveler had of finding “‘the dark lugubrious, somber, impenetrable jungles of the Wilderness.’” In obvious disillusionment, he “saw nothing particularly ‘wild,’ ‘weird,’ or ‘howling,’ about the Wilderness” and contented himself with observing, “it was not the most interesting country to be sure.”

Some modern accounts of the Battle of the Wilderness continue to reflect similar themes. In A Stillness at Appomattox, Bruce Catton’s Wilderness “was a mean gloomy woodland…lying silent and forbidding.” Edward Steere’s study of the Wilderness Campaign called the Wilderness “a dreary wasteland” and a “brooding jungle” that set “eternal shadows over stagnant pools and marshy creek bottoms” and “imposed the conditions of combat in its gloomy depths.” While James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom was more subdued, portraying the Wilderness as “that gloomy expanse of scrub oaks and pines,” Mark Grimsley’s history of the Overland Campaign painted the Wilderness as a “country [that] seemed to hate every man who dared walk through it.” Such depictions suggest that while the region’s image evolved during the war years, becoming increasingly negative, the postwar interpretation became a static, if not exaggerated, rendition—the malevolent Wilderness—that received the sanction of tradition while losing none of the image’s appeal.

Just as the Wilderness morphed into a malevolent landscape, it also became associated with death and destruction. The association is a key element in its mystique. This process began with the Overland Campaign, as Union soldiers began the march south. After the Battle of the Wilderness, the men remarked on the carnage as well as the destruction of the vegetation during that engagement and were amazed that anyone could have survived. Burial parties also collected the remains of the killed. Later visitors to the battlefield remarked on the ruined vegetation and the shadow of death over the land. Those who wrote about the Wilderness in postwar histories and memoirs continued this association with death and brought it to its highest form.

At the start, as well as the conclusion, of the Battle of the Wilderness, Federal soldiers passed through the old Chancellorsville battleground and saw the ruins, the debris, and especially the dead. William D. Landon of the 14th Indiana made such a visit and noted that “strange feelings crept over me as we marched along the same road and over the same ground where one year and a day before I had stood up with my comrades in line of battle,” seeing also “the old white house occupied as headquarters by Gen. [Darius] Couch [2nd Corps] during the fight, shattered and torn with hostile shot and shell, still standing, a refuge for bats and owls (ghosts, too, for aught I know).” In contrast, soldiers from the 86th New York focused on the graves. They found the old battlefield “covered with” them, and during one night they “slept among the graves of their comrades who fell just one year ago to-day.”

Perhaps most unnerving of all were the skeletons of troops killed a year earlier. The woods were strewn with the skeletons of comrades killed here one year ago,” remarked Landon. Charles Brewster also found that “there were lots of human skulls and bones lying top of the ground and we left plenty more dead bodies to decay and bleach to keep their grim company.” If there was a perfect place to rehearse the graveyard scene from Hamlet, this was it.

During the Battle of the Wilderness, this association with death continued as soldiers witnessed the terrible toll exacted by an unseen foe. The Wilderness became a terrible place where soldiers went in whole and came out wounded or lifeless.

By the end of the fight, the Wilderness battlefield was covered with casualties, and in time it would be pocked with graves and littered with bones. Later, a Union soldier who returned after the battle to bury the dead observed that those who were farther than a mile away from the hospital “remain as death found them, with the exception of their clothing,” which had been removed. “It is estimated,” he went on, “that 15,000 of our men, and as many, or more, of Rebels lie here unburied; and as six weeks have passed since the battle, imagination in its wildest fancies cannot begin to paint the spectacle.” It is little wonder that he called the field of battle “this wilderness of death” and “this wilderness and shadow of death.”

John Trowbridge, a reporter who visited the battlefield after the war, discovered “the unburied remains of two soldiers” while making his way through the thickets. While disturbing, the sight of skeletons in the Wilderness was becoming increasingly rare as the U.S. government took steps in the war’s immediate aftermath to account for the Union dead, especially to identify and inter those who had not received a decent burial. One of the first efforts was at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania.

In June 1865, soldiers came back to the Wilderness to inter “the remains of Union soldiers yet unburied” while “marking their burial places for future identification.” Nevertheless, long after these efforts, an 1884 travel account warned those who would tour the Wilderness that “even now a straggler through the tangled and scrubby woods will occasionally come suddenly upon a skeleton with a few tattered threads of blue or gray clinging to the bones—a ghastly reminder of war’s grim horrors.”

Postwar visitors to the Wilderness understandably continued to connect the place with death. The region seemed to evoke a palpable feeling in many who visited it. Writing about a visit to the Chancellorsville battlefield, David McIntosh, a former Confederate artillery officer, sensed that “the spirit of death seemed still to brood over the place. Not a sound could be heard through all the forest, not the note of a bird. The silence and the gloom was painful.”

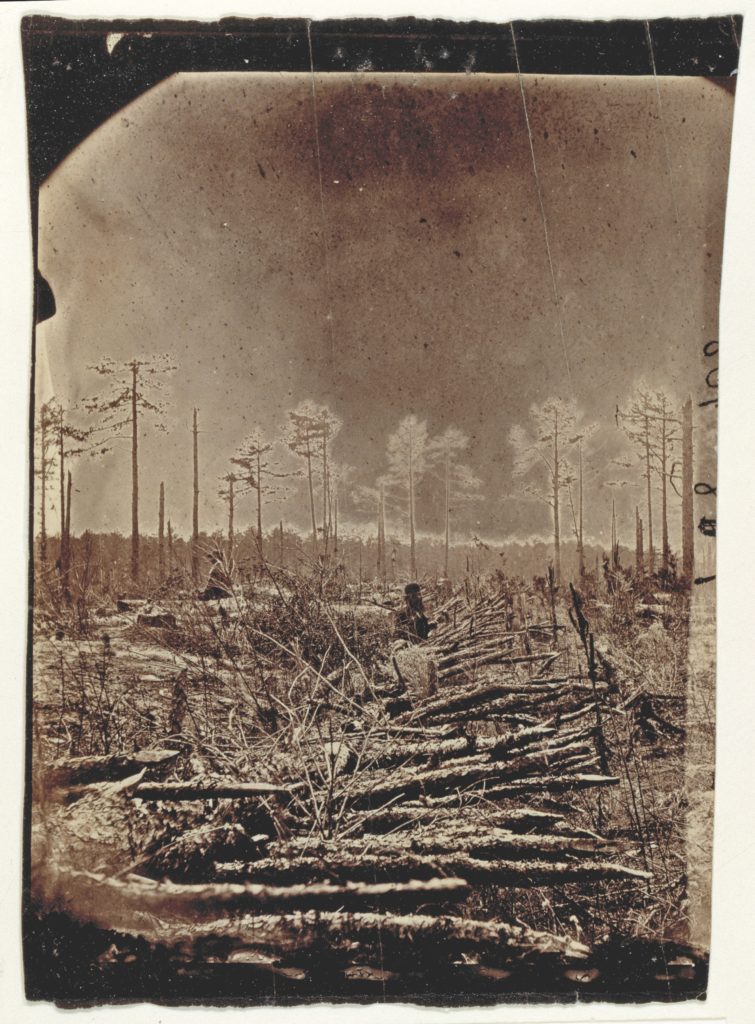

The ruinous state of the Wilderness also linked it to destruction, as attested to by both witnesses and contemporary photographs. The vegetation long remained scarred. In 1865, Trowbridge noted how “the marks of hard fighting were visible from afar off” at the Chancellorsville battlefield. West of the Chancellor house, Trowbridge found “the tree-trunks pierced by balls, the boughs lopped off by shells, the strips of timber cut to pieces by artillery and musketry fire.” One 1884 account claimed that “the woods still bear the marks of the fierce struggling…and although the lapse of time and nature’s softening touches have to a great extent obliterated the traces of battle, yet the larger trees are scarred…and here and there a shell-mark shows itself.”

Postwar writers cemented this association of the Wilderness with death and destruction. William Swinton wrote of “a region of gloom and the shadow of death.” Here in this “horrid thicket there lurked two hundred thousand men; and, though no array of battle could be seen, there came out of its depths the crackle and roll of musketry like the noisy boiling of some hell-caldron that told the dread story of death.” For the soldiers who fought in the Wilderness, the forest was a place where death held sway. It was everywhere to be found, from the remnants of Chancellorsville to the terrible toll in killed and wounded, from the toppled trees to the buried bodies and bleaching bones. For this reason, Union veterans like Horace Porter almost seemed compelled to connect the two. For him, the Wilderness would always be “a tangled forest the impenetrable gloom of which could be likened only to the shadow of death”—and thus the Wilderness and death became one and inseparable, a legacy that lives on.

This, then, was the aura that came to surround the Wilderness, a mystique that has continued to the present day. There were many woodlands in which Civil War soldiers fought, even ones similar to the Wilderness, such as Chickamauga in Georgia, yet there was only one Wilderness. Only one carried the name. Only one became the malevolent woods where soldiers would find death and hell with accompanying spirits. Why was this the case? It is undeniable that terrible things happened in the Wilderness— thousands of men died there, not a few of them at the hands of the merciless flames. Yet there were other battlefields noted for slaughter and still others in which forest fires took their toll among the wounded. What made the Wilderness different?

The size of the seemingly interminable Wilderness unquestionably set it apart and awed those who entered. Moreover, repeated visits led the soldiers’ understanding of the region to evolve. The very name evoked the animus between man and untamed nature, while its decayed landscape provided a gloomy backdrop for the fighting that occurred. Any analysis of why the soldiers set the Wilderness apart in their minds and memories would be incomplete, though, without acknowledging the supreme importance of the Wilderness in this process. Without that bloody engagement, it is doubtful the region would have received the notoriety it did. Depictions of the Wilderness became decidedly negative in the battle’s aftermath, and through these travails the mystique was born. The Wilderness’ wounds have healed, the armies have left, and the dead have returned to Mother Earth. But the mystique lives on, and will do so as long as men remember what happened in that Virginia forest so long ago.

Hell-Cauldron

If the Wilderness was a place of death akin to hell, then it is only natural that some postwar authors portrayed the region as a haunt of ghosts and spirits. One Federal, returning to the battlefield to look for his fallen brother, found partially exposed bones. He tried to pull on one of them but found that “something at the other end seemed to detain it, and…stopped suddenly as if the dead man himself had put his scrawny hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Don’t disturb my bones with such rude hands.’” The notion “that lifeless bones should make resistance as though still animated by an unwilling spirit, filled [him] with dread and [he] hurried away.”

Others saw it as a land where spirits ambled about; one Confederate calling it “a place of gloom, the home of the snake, the bat, and the owl….” Morris Schaff, a Union veteran of the battle, portrayed the region as an avenging spirit that intervened to defeat the Confederates and strike down slavery. The slaves who had tended the iron furnaces and cut down the original forest had suffered great wrongs, he writes—injustices for which the forest set out to exact revenge. At the Wilderness, Schaff observes, R.E. Lee had not “reckoned upon a second intervention of Fate: that the spirit of the Wilderness would strike Longstreet just as victory was in his grasp, as it had struck Stonewall.”

Schaff posits that Stonewall’s ghost appears, wandering nearby Chancellorsville while the “Spirit of the Wilderness” stalks him in the brush. Upon running into “a gaunt, hollow-breasted, wicked eyed, sunken-cheeked being,” his ghost is beseeched: “Stonewall, I am Slavery and sorely wounded. Can you do nothing to stay the Spirit of the Wilderness that, in striking at me, struck you down?” As Longstreet’s May 6 flank attack reached the height of its success, Schaff writes that Slavery rejoiced: “Frenzied with delight over her prospective reprieve, [she] snatches a cap from a dead…Confederate soldier, and clapping it on her coarse, rusty, gray-streaked mane, begins to dance in hideous glee.” Schaff warns Slavery to “dance on, repugnant and doomed creature! The inexorable eye of the Spirit of the Wilderness is on you!…For in a moment Longstreet, like ‘Stonewall,’ will be struck down by the same mysterious hand, by the fire of his own men, and the clock in the steeple of the Confederacy will strike twelve.”

Adam H. Petty is a historian and documentary editor for the Joseph Smith Papers. He earned his bachelor’s in history from Brigham Young University and his Ph.D. in history from the University of Alabama, studying under George Rable.

Adapted with permission from The Battle of Wilderness in Myth and Memory by Adam H. Petty © 2019, LSU Press.