For some a secular saint, for others a symbol of oppression

THE 718 MONUMENTS, installed during the century after the Civil War, decorated town squares, courthouse lawns, and city centers across the South, out west, and north of the Mason-Dixon line. These images portrayed Confederate politicians, generals, and, often, a generic soldier. Southerners bragged of emplacing more memorials “than have ever been erected in any age of the world to any cause, civil, political, or religious.” The Confederate most replicated in metal and stone, Robert E. Lee, had led the Army of Northern Virginia. He became the South’s icon—but symbolism is in the eye of the beholder.

Before April 20, 1861, when he resigned from the U.S. Army to fight for the South, Robert E. Lee seemed bound for neither canonization nor denunciation. A Revolutionary War hero’s son and a former West Point superintendent, Lee was a professional soldier on an upward but ordinary career arc. During the Civil War his trajectory changed radically. The Confederacy’s most gifted commander, he may have done more with less in combat than any American general ever. Southerners called him “Granny Lee” for his caution. His staff called him “The Great Tycoon,” a nod to his leadership. His troops said “Marse Robert,” a term of endearment and slave argot for “master.”

Rebelling against the United States cost Lee dearly. He lost the Confederate nation he fought for. He lost his family’s Potomac River estate. He lost his rights as an American citizen. Only after his death in 1870 did recognition evolve into adoration, as acolytes employed his memory and his image to recast the Confederacy and its history in terms soothing to southern sensibilities. Lee became touchstone and tinder, beatified and vilified, praised as a figure of principled valor and scorned as a booster of the “peculiar institution.” His presence in marble and bronze offers insights into how Americans have handled the legacy of the nation’s most consequential war and that of slavery, that war’s cause. Presidents have extended Lee degrees of redemption, but the broader public has demonstrated repeatedly that it has not forgotten or forgiven.

Born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1807, Lee was an aristocrat. His father, Harry “Light Horse” Lee, had ridden to glory in the Revolution and politicked his way to influence in Virginia. Robert’s wife, Mary, was a descendant of Martha Washington. In 1829, Lee graduated from the U.S. Military Academy second in a class of 46. Classmates dubbed their reserved companion the “Marble Model” for being the first graduate to leave West Point without even one demerit. He saw peacetime duty as an engineer and combat in the Mexican War. He spent two and a half years as superintendent at his alma mater. All the while, the national debate over slavery was intensifying. “In this enlightened age,” Lee wrote to Mary in 1856, “there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil.” Nevertheless, he insisted to her that slaves “are immeasurably better off here than in Africa.” He endorsed “painful discipline” as “necessary for their instruction as a race.”

In 1857, George Washington Parke Custis died, bequeathing to daughter Mary his 1,100-acre estate, Arlington, across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. The property included 196 slaves. Custis had named Lee executor. Custis’s slaves claimed that on his deathbed he had promised them their freedom upon his death, but his will said his executor could keep them in bondage as long as five more years. Lee freed none any earlier. Defiant slaves “refused to obey orders & said they were as free as I was,” Lee complained in a letter to his son, and “resisted till overpowered.”

In 1859, three slaves—two male and one female—fled the plantation. When they were caught, Lee had the county constable uncurl the whip—50 lashes for the men, 20 for the woman—and salt their wounds with brine, Wesley Norris, one of the men flogged, recalled later. The same year, Lee led U.S. Marines in retaking the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, that abolitionist John Brown and followers had seized in a failed bid to ignite a regional slave rebellion.

As the 1860 election neared, Southern states insisted that unless they could keep slavery, they would leave the Union. Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6. On December 20, South Carolina seceded. Other states followed. The Confederate States of America took form under a constitution guaranteeing “the right of property” in slaves. Its vice president, Alexander Stephens, declared slavery and white supremacy the would-be nation’s cornerstones.

On April 17, 1861, five days after rebel forces attacked Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina, Virginia seceded. Needing a leader for his army, President Abraham Lincoln had a friend, Francis P. Blair, meet Lee on April 18, 1861, with an offer to assign him command of the Union army. Lee declined. “How can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?” he asked Blair. Two days later, Lee resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy, first as a military advisor to President Jefferson Davis, then as the main Confederate army’s commander, looking the part at 5’10½” and weighing 165 lbs. with a distinctive beard and stern visage.

In May 1861, Union troops seized the Custis-Lee plantation. Soldiers liberated the slaves at Arlington long before Lee officially freed them by filing a deed of manumission on December 29, 1862. Mary Lee fled to Richmond. Her enforced absence from Arlington made tax payments—including a federal levy on property in “insurrectionary districts”—problematic. She sent a cousin to Union-held Alexandria, Virginia, to pay an outstanding $92.07 tax balance. Federal officials said they would accept payment only from the owner, and only if she appeared in person. Taxes on the estate, garrisoned by federal troops and home to freed blacks, went unpaid. At a January 11, 1864, tax sale, the U.S. government bought Arlington for $26,800, well below market value. Union Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, who wanted turncoat officers hanged as traitors, dedicated parts of the plantation, including Mary Lee’s rose garden, as a burial ground that became Arlington National Cemetery.

On April 9, 1865, with Union forces surrounding his army near Appomattox, Virginia, Lee was pondering surrender when fellow general Edward Porter Alexander proposed breaking the Army of Northern Virginia into small bands to wage guerrilla war. Lee refused. “We must consider its effect on the country as a whole. Already it is demoralized by the four years of war,” he told Alexander. “We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.” Lee surrendered that day.

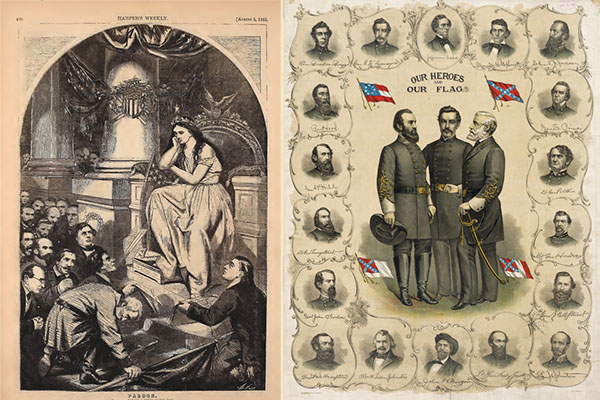

Triumphant—Harpers Weekly portrayed Lee kowtowing to the goddess Columbia, popular at the time as a national emblem—but bereft at Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, the North rang with demands to try Confederate leaders for treason. Instead, President Andrew Johnson not only pardoned the rebel rank and file en masse but offered higher-ups pardons, too—if they asked. Within a fortnight, Lee requested a pardon. On October 2, 1865, he re-swore allegiance to the United States in a signed oath and urged other former rebels to do the same. “I believe it to be the duty of every one to unite in the restoration of the country,” Lee told a friend. Johnson, beset by radical Republican efforts to impeach him, never acted on Lee’s pardon application (“Power to Pardon,” April 2018).

After the war, Lee lived quietly. He hardly ever read newspapers and kept his opinions to himself. However, on February 17, 1866, the congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction called him in to testify on post-war attitudes in the South. In sworn testimony, Lee endorsed education for freed slaves but said he doubted blacks were “as capable of acquiring knowledge as the white man is.” He opposed black suffrage, he told the committee, because enfranchising freedmen would “excite unfriendly feelings between the two races” and “open the door to a great deal of demagogism.” Two months later, Wesley Norris’s account of the 1859 flogging at Arlington appeared in print, along an assertion by Norris that George Washington Custis had promised on his deathbed that upon his death his slaves were to be freed. Publicly, Lee said nothing about Norris’s account of the whipping. Privately he fumed. “No servant, soldier, or citizen that was ever employed by me can with truth charge me with bad treatment,” he wrote to a friend. Lee also wrote to Amanda Parks, a former Custis slave, to apologize for being elsewhere when she had paid a social call, “for I wished to learn how you were, and how all the people from Arlington were getting on in the world.”

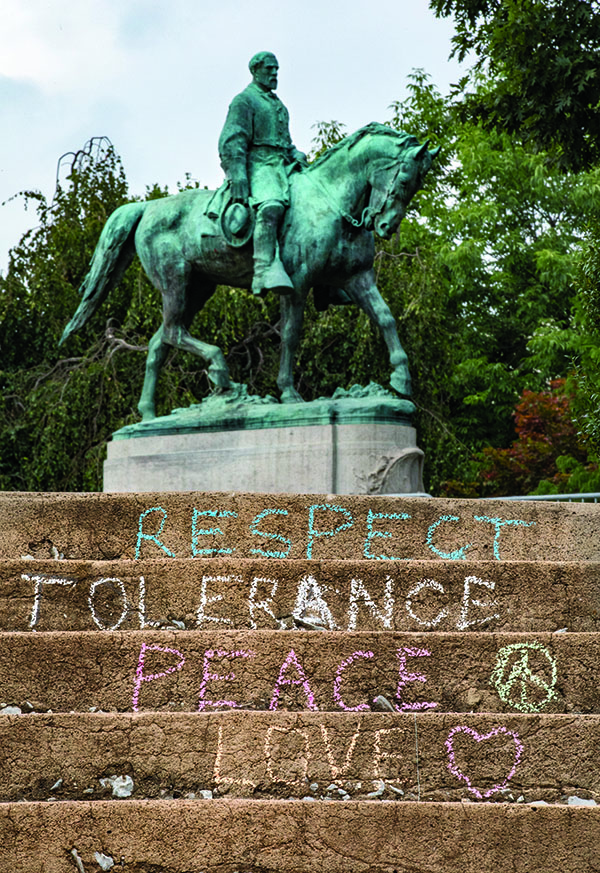

Lee was in living in Lexington, Virginia, presiding over Washington College, now Washington & Lee University, when, on Christmas Day 1868, Johnson granted a blanket amnesty to all “who, directly or indirectly, participated in the late insurrection or rebellion.” That action applied to Lee. In 1869, Lee declined to support installation of “enduring memorials of granite” on the Gettysburg battlefield. “I think it wiser moreover not to keep open the sores of war,” he wrote to David McConaughy, secretary of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, “but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife & to commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered.” An equestrian statue of Lee now stands on the battlefield. In March 1870, Lee was passing through Augusta, Georgia, when admirers surrounded him, including Augusta resident Woodrow Wilson, 13, who squirmed through the crowd until he was standing alongside the former general.

Lee’s death on October 12, 1870, plunged the South into gloom. In Richmond, “everywhere were to be seen evidences of the depression caused by Virginia’s great affliction,” the Daily Dispatch wrote. Many homes and businesses displayed images of Lee draped in black. In the former Confederate capital, the New York Herald reported, “everybody feels as if they had lost a friend.”

On October 24, former Confederate general Jubal A. Early published an open letter asking rebel veterans to meet November 3 in Lexington to plan a Lee memorial. The goal, an organizer said, was a monument that “will cause all who gaze upon it to feel their hearts more pure, their gratitude more warm, their sense of duty more exalted.”

Pride and defiance fueled the memorial campaign, which went far beyond honoring Lee. “The world must be made to know that Confederate soldiers are not ashamed of the great struggle they made for constitutional liberty, and regret nothing, in that respect, except that they failed to accomplish their great purpose,” Early told veterans at Lexington.

Meanwhile, Mary Lee was trying to reclaim Arlington. Senator Thomas C. McCreery (D-Kentucky) urged Congress to investigate the forced tax sale. Congress refused; the Lee family sued. In 1882, the Supreme Court held the seizure illegal, invalidating the rule that a landowner had to appear in person to pay property taxes. Arlington National Cemetery counted nearly 20,000 graves. Stuck, the government negotiated and once again bought Arlington, this time for $150,000. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln authorized payment to the Lees on May 12, 1883.

By the mid-1880s, the Lee Monument Association had raised $75,000. A Richmond man donated acreage for the memorial. The association wanted a Southern designer, but, Harper’s noted, the South had “few sculptors of eminence” and hiring a Yankee artist was out of the question. The commission—$18,000 for a 21-foot bronze of a uniformed Lee astride Traveller—went to Marius Jean Antonin Mercie, a Parisian sculptor and painter known for epic statuary. A suitable 40-foot granite pedestal, designed by French architect Paul Pujol, cost $42,000.

In 1890, after temporarily assembling his work for a brief display in Paris, sculptor Mercie shipped the components in four crates to New York for transfer by rail to Richmond. The largest, containing the six-ton bronze of Traveller, was 18 feet long, seven feet high, and six feet wide.

On May 7, 1890, some 9,000 men and women, harnessed to wagons, pulled the crates nearly a mile from the Richmond rail station to the site at Monument and Allen avenues. “Never were such crowds seen in Richmond as thronged Broad and Franklin streets during the passage of the procession,” an observer said. Confederate veterans patrolled the grounds day and night while crews worked on the statue, set facing south.

Dedication day, May 29, 1890—a balmy, cloudless Thursday—drew tens of thousands to Richmond, described by a newspaper as “splendidly decorated, better than ever before known.” Many were Confederate veterans massing with comrades for the first time since 1865. Some carried battle-worn flags. Hearing bands play “Dixie,” men wept. Former generals Early, Joseph Johnston, Wade Hampton, and James Longstreet, as well as the widows of Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart attended. Johnston, eldest officer among the dignitaries, unveiled the statue to cheers and cannon and rifle salvos. “Hats and handkerchiefs were thrown in the air as such was never seen before,” a newspaper reported. Confederate flags proliferated, many supplied by the only outfit still making them: Lowell, Massachusetts-based U.S. Bunting, owned by former Union general Benjamin F. Butler.

Keynote speaker and ex-colonel Archer Anderson called Lee a reflection of godly “attributes of power, majesty, and goodness” and “the purest and best man of action whose career history has recorded.” Virginia Governor Philip W. McKinney said critics of Lee and the Confederacy “may as well find fault with nature’s God because He kisses Confederate graves with showers and smiles upon them with His sunshine and garlands them with flowers.”

Not all rejoiced. Honoring the Confederacy, wrote the Richmond Planet, an African-American newspaper, “serves to reopen the wound of war and causes to drift further apart the two sections. It furnishes an opportunity for designing politicians in both political parties to take advantage of the situation and the country suffers.” Abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass derided the “bombastic laudation of the rebel chief.”

Jim Crow took hold in the South, the repressive code’s presence enlarging further in 1896 when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that separate but equal was equal. In this era, nationalism surged. In 1898, Congress removed the only remaining sanction against former rebels—Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which had barred from federal office any official of the United States who had participated in the rebellion.

Between 1890 and 1920, nearly 400 Confederate monuments, including many portraying Lee, went up. Lobbying elevated Lee from sectional beau ideal to national figure. “The South made its big medicine out of Lee: victory out of defeat, success out of failure, virtue out of fault, unionism out of secession, a New South out of an Old South—all accompanied by piercing rebel yells,” wrote historian C. Vann Woodward. “And the Yankees loved it.” Lee was, historian Peter S. Carmichael wrote, “metaphorically resurrected into a Christlike figure of perfection and the embodiment of the Lost Cause.”

In “Robert E. Lee,” a poem honoring Lee’s 1907 centennial, Julia Ward Howe, composer of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” eulogized him as “a gallant foeman in the fight/A brother when the fight was o’er.” President Theodore Roosevelt praised Lee’s “serene greatness of soul characteristic of those who most readily recognize the obligations of civic duty.” In 1909, Virginia politicians had a bust of Lee placed in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. In 1923, artist Gutzon Borglum, later the auteur of Mount Rushmore, began carving a relief of Lee into Stone Mountain, Georgia. In 1909, future President Woodrow Wilson, who at 13 had met Lee, called honors for him a “delightful thing,” proving “we are a nation and are proud of all the great heroes whom the great processes of our national life have elevated into conspicuous places of fame.” In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated a Lee statue in Dallas, Texas, to “one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”

Since Emancipation, African-Americans have struggled to be treated as American citizens. After World War II, as Supreme Court decisions and public sentiment began to tip their way, the cult of the Confederacy persisted, even intensified. In 1948, Baltimore’s mayor drafted Lee into Cold War service. “With our nation beset by subversive groups and propaganda which seeks to destroy our national unity, we can look for inspiration to the lives of Lee and Jackson to remind us to be resolute and determined in preserving our sacred institutions,” Thomas D’Alesandro Jr. said. In 1959, the U.S. Navy named a submarine for Lee. A year later, John F. Kennedy, campaigning for the presidency in North Carolina, extolled Lee as a man who “after gallant failure, urged those who had followed him in bravery to reunite America in purpose and courage.”

In the years between 1950 and 1970, states and municipalities, located mainly in what once was the Confederacy, constructed nearly 50 monuments and named 39 public schools to honor Confederates, including Robert E. Lee. In 1972, carvers finally completed Gutzon Borglum’s relief at Stone Mountain, Georgia, posing Lee riding with Stonewall Jackson and Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

In 1975, Congress purported to restore Lee’s “full rights of citizenship.” Sponsoring Senator Harry F. Byrd, Jr. (I-Virginia) claimed President Andrew Johnson had failed to act on Lee’s 1865 pardon application because officials had mislaid Lee’s oath of allegiance. The oath had turned up in 1970, Byrd said, urging Congress to pass a resolution ceremonially restoring Lee’s right to hold federal office. Checking with the National Archives, Representative John Conyers (D-Michigan) found what he called the “romantic notion of the lost oath” to be untrue; Johnson had passed on Lee’s application for political reasons. In any event, Conyers added, Johnson’s 1868 general amnesty covered Lee. And in 1898 Congress had removed the 14th Amendment bar on federal office applying to Lee. Nevertheless, both chambers approved Byrd’s proposed gesture. Signing the resolution on August 5, 1975, President Gerald Ford called Lee “the symbol of valor and of duty.”

However, in recent decades the national tenor toward Confederate decoration has shifted. In 2008, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-California)—who was eight when her father, Baltimore Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro, hailed Lee as a theoretical cold warrior—had the Lee bust removed from Statuary Hall and stowed in a corner of the Capitol called “the crypt.” The June 17, 2015, murder by an avowed white supremacist of nine congregants at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, accelerated calls to take down totems of the Confederacy. The statue FDR dedicated is in storage. New Orleans dismantled its Lee statue. The bronze in Richmond was an issue in Virginia’s 2017 gubernatorial race and remains one.

Admirers have fought back. The United Daughters of the Confederacy insists members are honoring their ancestors and advocating a “truthful history of the War Between the States.” Conservative online commentator Jack Kerwick sees a crusade intent on “the cleansing from the Western world of all white figures from our past who fail to satisfy the left’s contemporary ‘progressivist’ litmus test.” Donald W. Livingston, a former professor at Emory University, derides assertions that the Civil War was a moral struggle over slavery as “Marxist-style analysis.”

Monuments have power. Admirers of the Confederacy wanted to justify, honor, and enshrine their region’s past. In refusing to endorse monuments at the Gettysburg battlefield in 1869, Lee acknowledged that memorializing the Confederacy would keep open wounds from war. Clearly, those wounds remain unhealed.