Sure, we’ve all heard the tales of George Washington’s exploits, Paul Revere’s famous “one if by land, two if by sea” ride, Benjamin Franklin’s role in well, just about everything. But what about the foreign fighters that served with distinction, nay, may have even saved the revolution?

Here are seven foreigners who freely joined the fight for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

1. Baron von Steuben: Fraud Turned Hero

The Prussian’s resume was impressive. America’s diplomats in Paris, Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, claimed he was once the major general and quartermaster general in the Prussian army, as well as a one-time aide-de-camp to the legendary warrior-king Frederick the Great. But Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin von Steuben, or Frederick William Augustus, Baron de Steuben, was a fraud. He had been none of those things.

And yet in America, he became a hero.

“[M]ore than any other individual,” writes historian Paul Lockhart, Baron von Steuben “was responsible for transmitting European military thought and practice to the army of the fledgling United States. He gave form to America’s first true army — and to those that followed.”

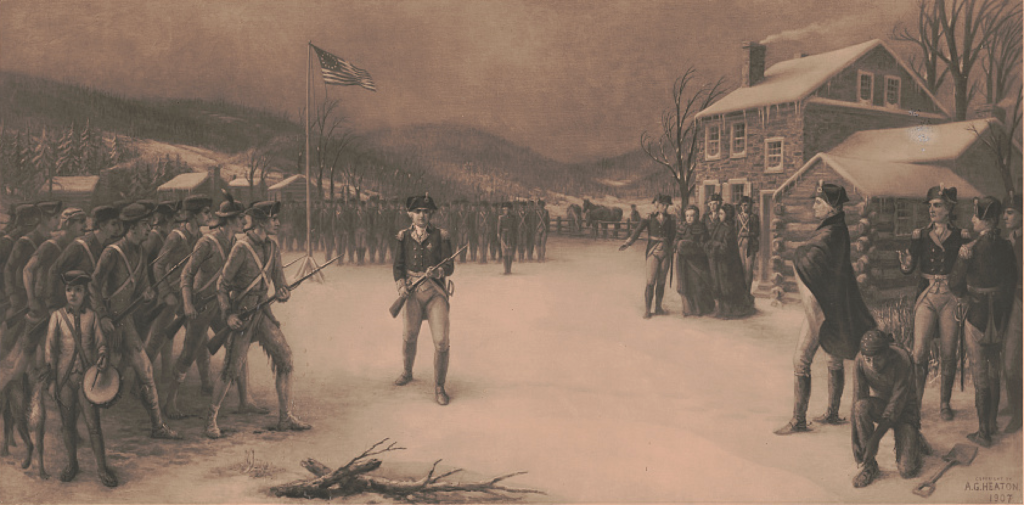

Despite his bolstered resume, the 47-year-old was a career soldier and did in fact have a keen military eye. He brought to the Continental Army a wealth of European military experience to rally an ill-clothed, starving and poorly trained army at Valley Forge into a professional force. There, von Steuben introduced discipline, putting Washington’s entire army through Prussian-style drills. He noted to Washington that short enlistments meant constant turnover at the expense of order. There was no codified regiment size and different officers throughout the Continental Army used different military drill manuals meant chaos if other units attempted to work with one another.

“[It was] Steuben’s ability to bring this army the kind of training and understanding of tactics that made them able to stand toe to toe with the British,” historian Larrie Ferreiro told the Smithsonian.

Appointed inspector general of the Continental Army in May 1778, von Steuben’s methods categorically transformed the fledgling patriots before going on to write “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States,” the first military manual for the American army.

2. Casimir Pułaski: NO ENGLISH, ALL COURAGE

“In the 13 months since the United States had declared its independence from Great Britain, the Continental Congress had been unable to develop an effective mounted force or find men who could organize, lead and train one,” writes Ethan S. Rafuse. Yet in December 1776, after numerous defeats and retreats, Gen. George Washington called on the Continental Congress to change that.

“I am convinced there is no carrying on the War without them,” he wrote to John Hancock, “and I would therefore recommend the Establishment of one or more Corps…in Addition to those already raised in Virginia.”

Enter Casimir Pułaski.

Born into Polish nobility, Pułaski had made a name for himself under the Knights of the Holy Cross — the military arm of the Confederation of the Bar that opposed Russian rule.

As a cavalry commander, Pułaski earned widespread acclaim for his 1771 defense of the hallowed monastery of Częstochowa against 3,000 Russians.

However, the Pole was soon forced to flee and found himself in dire financial straits in France. He was soon offered a lifeline by Benjamin Franklin, who agreed to pay for Pułaski’s trip to America in June of 1777.

According to Rafuse, Franklin wrote to Washington lauding Pułaski as “an officer famous throughout Europe for his bravery and conduct in defense of the liberties of his country against the three great invading powers of Russia, Austria, and Prussia” and suggesting that he might “be highly useful to our service.”

First an aide to Washington, Pułaski was soon made brigadier general in the Continental cavalry — where, despite not speaking a word of English, soon proved his mettle.

By 1778, Pułaski was awarded command of the “Pulaski Legion,” an independent cavalry unit composed of American and foreign recruits. The following spring Pułaski and his Legion made their way south to defend the besieged city of Charleston. In October that year, Pułaski was mortally wounded by a grapeshop while leading a cavalry charge during the Siege of Savannah. The 34-year-old’s heroic death established him among the American Revolution’s most famous foreign volunteers and earned him the moniker as the “Father of American Cavalry.”

3. Michael Kováts: HE WAS HUNGARY FOR BATTLE

While Pułaski might be known as the Father of American Cavalry, Michael Kováts de Fabricy shouldn’t be overlooked.

He arrived in America four months prior to Pułaski after declaring to Benjamin Franklin, “I am a free man and a Hungarian. I was trained in the Royal Prussian Army and raised from the lowest rank to the dignity of a Captain of the Hussars.”

“Kováts had an even more impressive military record than Pułaski,” according to Rafuse. “Born in Karcag, Hungary, in 1724, Kováts belonged to a noble family whose history of service to the Hungarian crown went back centuries. In Hungary as in Poland, cavalry was the most important element of the army, and for the same reasons: the country’s open plains and acquisitive neighbors — in Hungary’s case, Habsburg Austria and the Ottoman Turks.”

Kováts forged a fiercesome reputation as a brave and effective officer, declaring that he rose through the ranks, “not so much by luck and the mercy of chance than by the most diligent self-discipline and the virtue of my arms.”

As a mercenary soldier, Kováts found himself training participants in Poland’s nascent patriot movement, which included members of the Pułaski family. Like Pułaski, Kováts soon found himself in France and then on a ship to the fledgling nation of America to offer his services to the revolution.

Despite struggling to gain a commission, Kováts eagerly began training men within the Pułaski Legion in April 1778. In his new unit, writes Rafuse, Kováts “particularly emphasized the ‘free corps’ concept popular in Europe in the 1740s and 1750s. To preserve the strength of their rigorously drilled and tightly disciplined battalions of infantry, Eastern European military leaders began accepting into their service units of light forces to operate around the fringes of their armies.” It was here that, under Pułaski, Kováts was able to organize and train one of the first hussar regiments in the American army.

Kováts was mortally wounded by a rifle shot during a clash with the British on May 11, 1779, in defense of Charleston.

4. Tadeusz Kościuszko: LOSER IN LOVE, WINNER IN WAR

Commissioned a colonel by the Continental Congress in 1777, the 30-year-old Kościuszko soon established himself as one of the Continental Army’s most brilliant, and much needed, combat engineers — all thanks to an unsuccessful attempt to elope with a lord’s daughter back in Poland.

After discovering his brother had spent all the family’s inheritence, Kościuszko was hired to tutor Louise Sosnowska, a wealthy lord’s daughter. The pair fell in love and attempted to elope in the fall of 1775 after Lord Sosnowski refused Kosciuszko’s request. According to the Smithsonian, “Kosciuszko told various friends, Sosnowski’s guards overtook their carriage on horseback, dragged it to a stop, knocked Kosciuszko unconscious, and took Louise home by force.”

Broke, heartbroken, and perhaps fearing repercussions for his actions, Kościuszko set sail across the Atlantic in June 1776. Upon arriving in Philadelphia, John Hancock appointed him a colonel in the Continental Army that October, and Benjamin Franklin hired him to design and build forts on the Delaware River to help defend Philadelphia from the British navy, writes the Smithsonian.

The Pole oversaw the damming of rivers and flooded fields to stem a British pursuit following their victory at Fort Ticonderoga in 1777. This action bought time for the patriots to regroup and prepare for their first major victory of the war — Saratoga. Fortifying Bemis Heights overlooking the Hudson, Kościuszko’s design contributed to the surrender of General John Burgoyne and precipitated the French’s entry into the war.

From there, Kościuszko’s oversaw the defense of West Point, with his fortifications so thorough that the British never deigned to attempt an assault.

At war’s end he was promoted to brigadier general with Thomas Jefferson praising the Pole, “As pure a son of liberty as I have ever known.”

5. Johann de Kalb: Died doing what he loved — Fighting Brits

Who hated the British most during this time period? The French yes, but Germans were a close second.

Born outside the Prussian city of Nuremberg, Baron Johann de Kalb entered the service of France and fought in the Seven Years’ War against the British. He eventually rose to officer rank and was made a Knight of the Royal Order of Merit, according to the American Battlefield Trust.

When the Revolutionary War broke out, the veteran soldier saw a chance not only to fight for the ideals of the Enlightenment but to strike a blow to his old foe the British.

Initially denied a commission, a furious de Kalb was making his way back to France when he learned that the Marquis de Lafayette had influenced Congress to appoint him as major general. De Kalb survived the infamous winter at Valley Forge with George Washington and Lafayette, before taking command of 1,200 Maryland and Delaware troops in the war’s Southern theater in 1780.

His command would, alas, be short.

On the morning of August 16, 1780, Gen. Horatio Gates deployed to meet Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis in the now famous Battle of Camden. When Gates and his inexperienced militia broke ranks and began to run only de Kalb was left to defend against Cornwallis.

De Kalb and his infantry refused to retreat. Yet somewhere in the midst of melee, de Kalb fell — downed by some 11 wounds, the majority from a bayonet. Taken as prisoner by the British, de Kalb survived for three more days before supposedly telling a British officer: “I die the death I always prayed for: the death of a soldier fighting for the rights of man.”

6. Bernardo de Gálvez: Our Spaniard in LouisianA

A best friend is one with deep pockets — especially when you’re trying to win a war. And although Bernardo de Gálvez was never a soldier in the Continental Army, he certainly had the means to help supply the revolution.

As governor of the Spanish province of Louisiana, Gálvez, according to American Battlefield Trust, “began to smuggle supplies to the American Rebels — shipping gunpowder, muskets, uniforms, medicine, and other supplies through the British blockade to Ohio, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia by way of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.”

When Spain joined in the war effort against the British, Gálvez didn’t miss a beat and began planning a military campaign against the British where he eventually captured Pensacola, Mobile, Biloxi and Natchez — all four formerly British ports.

However, Gálvez is best remembered for his role “in denying the British the ability to encircle the American rebels from the south by pressing British forces in West Florida and for keeping a vital flow of supplies to Patriot troops across the colonies,” during the rocky beginnings of the war.

Gálvez was officially recognized by George Washington and the United States Congress for his aid to the colonies during the American Revolution and remains one of eight people in history to receive honorary citizenship.

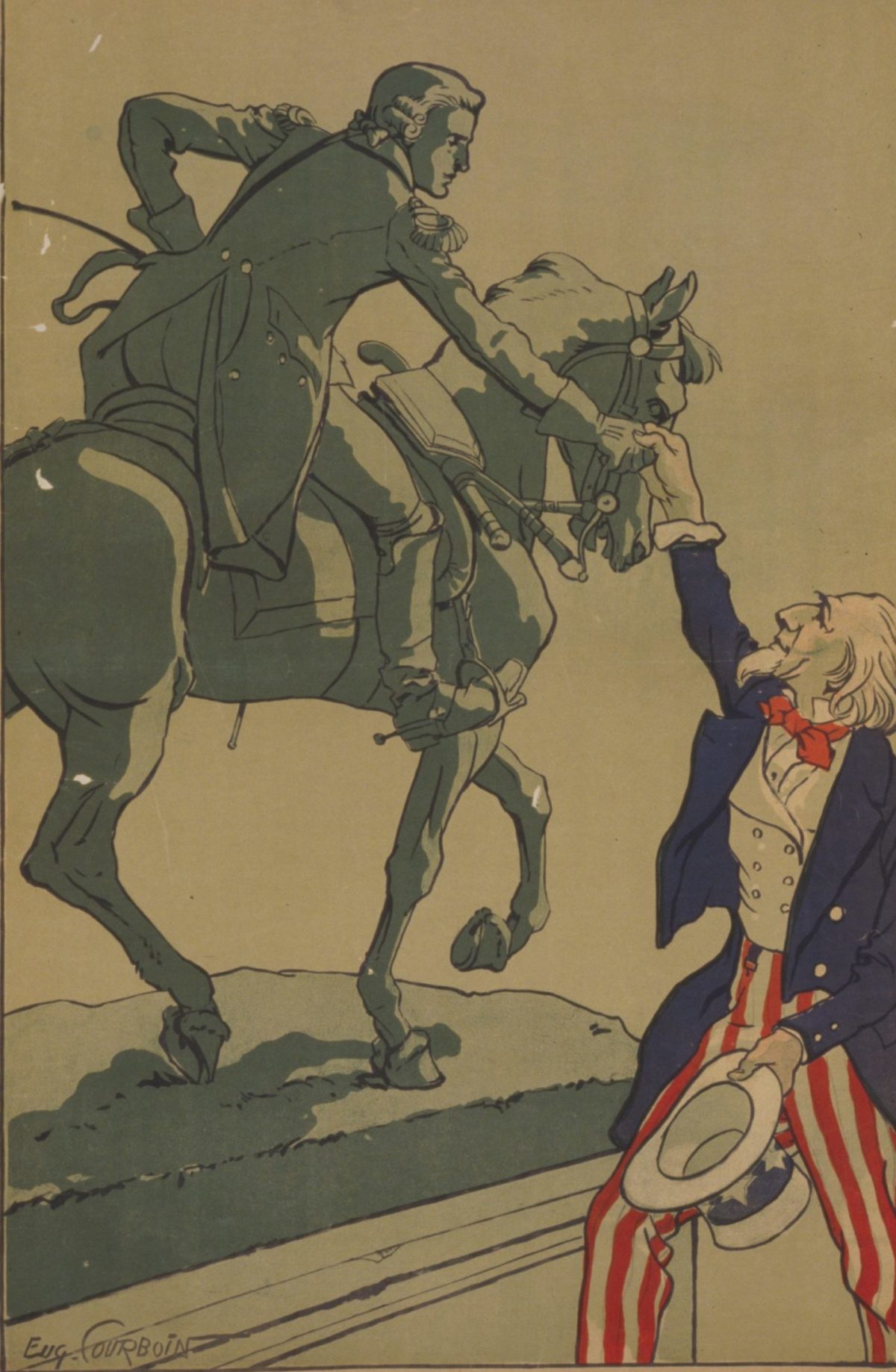

7. The Marquis de Lafayette: You Know This Guy

Last but certainly not least, Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette. The skinny, red-haired 19-year-old had a family tradition of fighting against the English.

Three hundred years before he was born, writes James Smart, “a Gilbert Motier had ridden beside Joan of Arc as a marshal of France. In 1759, when Lafayette was two, his father had been cut in half by a cannonball at the Battle of Minden during the Seven Years’ War. In the newly declared and still embattled United States of America, Lafayette probably hoped to run across William Phillips, the officer who commanded the artillery that killed his father.”

Despite a growing feeling of irritation among the Continental Congress due to the high number of French officers applying for commission, the wealthy Lafayette was willing to serve without a salary and pay for his own expenses.

Wounded while commanding a fighting retreat at the Battle of Brandywine on Sept. 11, 1777, Lafayette soon earned the trust and admiration of George Washington.

In November of that year, Congress voted Lafayette command of a division, where the boy general served with distinction at the battles of Gloucester, Barren Hill and Monmouth.

Lafayette was instrumental in rallying crucial support in France for the patriot cause. By 1781, the then 24-year-old had grown out of his moniker as “boy general” and took command of an army in Virginia, playing a pivotal role in the entrapment of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781, that eventually led to the conclusion of the Revolutionary War.

The general remains beloved in America to this day, with numerous streets, statues, and buildings erected and named throughout the United States in his honor.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.