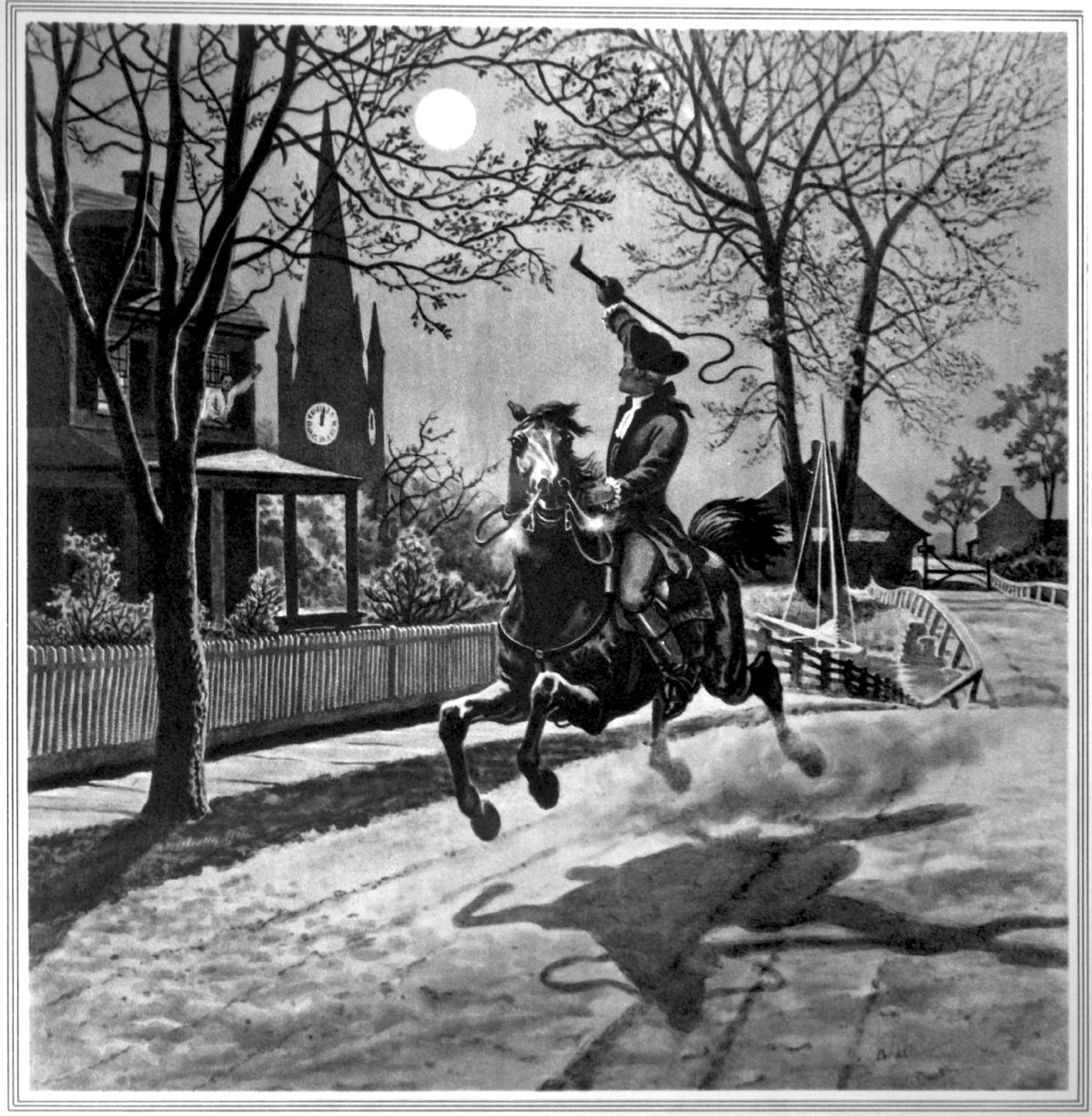

The enduring image of a lone Patriot nightrider rousing the countryside to arms has been burnished in American poems, books, and movies for two and a quarter centuries. The underlying message is always the same: A single brave man can make all the difference. In a letter written in 1798 to Massachusetts Historical Society founder Dr. Jeremy Belknap, Paul Revere described his actual adventures during his ‘Midnight Ride’ of April 18-19, 1775.

His mission was to warn of danger to Patriots outside Boston, particularly to two leaders who were opposing the government — Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Revere began his account by recalling suspicious activities of British forces in Boston during the week preceding April 18. His original letter to Belknap is the property of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

On Tuesday evening, the 18th, it was observed that a number of soldiers were marching towards the bottom of the Common. About 10 o’clock, Dr. Warren [Joseph Warren, one of the few Patriot leaders who had remained in Boston] sent in great haste for me and begged that I would immediately set off for Lexington, where Messrs. Hancock and Adams were, and acquaint them of the movement, and that it was thought they were the objects.

When I got to Dr. Warren’s house, I found he had sent an express [fast messenger] by land to Lexington — a Mr. William Daws [Dawes]. The Sunday before, by desire of Dr. Warren, I had been to Lexington, to Messrs. Hancock and Adams, who were at the Rev. Mr. Clark’s. I returned at night through Charlestown; there I agreed with a Colonel Conant [provincial militia veteran William Conant] and some other gentlemen that if the British went out by water, we would show two lanthorns [lanterns] in the North Church steeple; and if by land, one, as a signal; for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to cross the Charles River or get over Boston Neck. I left Dr. Warren, called upon a friend and desired him to make the signals.

I then went home … went to the north part of the town, where I had kept a boat; two friends rowed me across Charles River, a little to the eastward where the man-of-war Somerset lay. It was then young flood, the ship was winding, and the moon was rising. They landed me on the Charlestown side. When I got into town, I met Colonel Conant and several others; they said they had seen our signals. I told them what was acting [happening], and went to get me a horse; I got a horse of Deacon Larkin. While the horse was preparing, Richard Devens, Esq., who was one of the Committee of Safety, came to me and told me that he came down the road from Lexington after sundown that evening; that he met ten British officers, all well mounted, and armed, going up the road.

I set off upon a very good horse; it was then about eleven o’clock and very pleasant. After I had passed Charlestown Neck … I saw two men on horseback under a tree. When I got near them, I discovered they were British officers. One tried to get ahead of me, and the other to take me. I turned my horse very quick and galloped towards Charlestown Neck, and then pushed for the Medford Road. The one who chased me, endeavoring to cut me off, got into a clay pond near where Mr. Russell’s Tavern is now built. I got clear of him, and went through Medford, over the bridge and up to Menotomy. In Medford, I awaked the captain of the minute men; and after that, I alarmed almost every house, till got to Lexington. I found Messers Hancock and Adams at the Rev. Mr. Clark’s; I told them my errand and enquired for Mr. Daws; they said he had not been there; I related the story of the two officers, and supposed that he must have been stopped, as he ought to have been there before me. [At this point Hancock stated he intended to stay in Lexington and fight, and Adams vehemently disagreed, saying their job was political.]

After I had been there about half an hour, Mr. Daws came; we refreshed ourselves, and set off for Concord. We were overtaken by a young Dr. Prescott, whom we found to be a high Son of Liberty. I told them of the ten officers that Mr. Devens met, and that it was probable we might be stopped before we got to Concord; for I supposed that after night they divided themselves, and that two of them had fixed themselves in such passages as were most likely to stop any intelligence going to Concord. I likewise mentioned that we had better alarm all the inhabitants till we got to Concord. The young doctor much approved of it and said he would stop with either of us, for the people between that and Concord knew him and would give the more credit to what we said.

We had got nearly half way. Mr. Daws and the doctor stopped to alarm the people of a house. I was about one hundred rods ahead when I saw two men in nearly the same situation as those officers were near Charlestown. I called for the doctor and Mr. Daws to come up. In an instant I was surrounded by four. They had placed themselves in a straight road that inclined each way; they had taken down a pair of bars on the north side of the road, and two of them were under a tree in the pasture. The doctor being foremost, he came up and we tried to get past them; but they being armed with pistols and swords, they forced us into the pasture. The doctor jumped his horse over a low stone wall and got to Concord.

I observed a wood at a small distance and made for that. When I got there, out started six officers on horseback and ordered me to dismount. One of them, who appeared to have the command, examined me, where I came from and what my name was. I told him. He asked me if I was an express. I answered in the affirmative. He demanded what time I left Boston. I told him, and added that their troops had catched aground in passing the river, and that there would be five hundred Americans there in a short time, for I had alarmed the country all the way up. He immediately rode towards those who stopped us, when all five of them came down upon a full gallop. One of them, whom I afterwards found to be a Major Mitchel, of the 5th Regiment, clapped his pistol to my head, called me by name and told me he was going to ask me some questions, and if I did not give him true answers, he would blow my brains out. He then asked me similar questions to those above. He then ordered me to mount my horse, after searching me for arms. He then ordered them to advance and to lead me in front. When we got to the road, they turned down towards Lexington. When we had all got about one mile, the major rode up to the officer who was leading me and told him to give me to the sergeant. As soon as he took me, the major ordered him, if I attempted to run, or anybody insulted them, to blow my brains out.

We rode till we got near Lexington meeting-house, when the militia fired a volley of guns, which appeared to alarm them very much. The major inquired of me how far it was to Cambridge, and if there were any other road….[Revere then tells of his British escorts’ taking his horse and departing, and his walk back to Lexington in the dark.]

Came to the Rev. Mr. Clark’s house, where I found Messrs. Hancock and Adams. I told them of my treatment, and they concluded to go from that house towards Woburn….[After seeing the two Patriot leaders to safety, Revere chose to return to Lexington to help recover a trunk with Hancock’s confidential papers. There, at daybreak, he and his companion saw British troops moving into the town.]

We saw the British very near, upon a full march. We hurried towards Mr. Clark’s house. In our way we passed through the militia. There were about fifty. When we had got about one hundred yards from the meeting-house, the British troops appeared on both sides of the meeting-house….They made a short halt; when I saw, and heard, a gun fired, which appeared to be a pistol. Then I could distinguish two guns, and then a continual roar of musketry; when we made off with the trunk.

War had begun, and, as usual, truth was the first casualty. Without his consent or connivance, Revere was cast in the role of the solitary hero by the press, propagandists, and poets. By his own account, his actions that night were far less romantic than was popularly reported. He wrote about receiving much help, being rarely alone, and, due to a sound plan, Patriots alerting the countryside before he ever rose to the saddle. Paul Revere acted as a team member, an essential role if the goal of defeating the world’s greatest military power was to be realized.